Sinjar Mountains

| Sinjar Şengal | |

|---|---|

Satellite picture of Shingal Mountains | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 1,463 m (4,800 ft) |

| Coordinates | 36°22′0.22″N 41°43′18.62″E / 36.3667278°N 41.7218389°ECoordinates: 36°22′0.22″N 41°43′18.62″E / 36.3667278°N 41.7218389°E |

| Geography | |

The Sinjar Mountains[1][2] (Kurdish: Çiyayên Şengalê چیای شەنگال/شەنگار; Arabic: جبل سنجار jabal Sinjār; also Shingal\Shengar Mountains) are a 100-kilometre-long (62 mi) mountain range that runs east to west, rising above the surrounding alluvial steppe plains in northwestern Iraq to an elevation of 1,463 meters (4,800 ft). The highest segment of these mountains, about 75 km (47 mi) long, lies in Nineveh Governorate. The western and lower segment of these mountains lies in Syria which is about 25 km (16 mi) long and controlled by the de facto autonomous Syrian Kurdistan. The city of Sinjar is just south of the range.[3][4] These mountains are regarded as sacred by the Yazidis.[5][6]

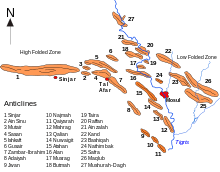

Geology

The Sinjar Mountains are a spectacular example of a breached anticlinal structure.[3] These mountains consist of an asymmetrical, doubly plunging anticline, which is called the Sinjar Anticline, with a steep northern limb, gentle southern limb and a northerly vergence. The northern side of the anticline is normally faulted, which results in the repetition of the sequence of sedimentary strata exposed in it. The deeply eroded Sinjar Anticline exposes a number of sedimentary formations ranging from Late Cretaceous to Early Neogene in age. The Late Cretaceous Shiranish Formation outcrops within the middle of the Sinjar Mountains. The flanks of this mountain range consist of outward dipping strata of the Sinjar and Aliji formations (Paleocene to Early Eocene); Jaddala Formation (Middle to Late Eocene); Serikagne Formation (Early Miocene); and Jeribe Formation (Early Miocene). The Sinjar Mountains are surrounded by exposures of Middle and Late Miocene sedimentary strata[4]

The mountain is a groundwater recharge area and should have good quality water, although away from the mountain groundwater quality is poor. Quantities are sufficient for agricultural and stock use.[7]

Sinjarite, a hygroscopic calcium chloride formed as soft pink mineral, was discovered in braided wadi fill in limestone exposures near Sinjar.[8]

Population and history

Since the 12th century,[9] the area around the mountains have been mainly inhabited by Yazidis[10] who venerate them and consider the highest to be the place where Noah's Ark settled after the biblical flood.[11] The Yazidis have historically used the mountains as a place of refuge and escape during periods of conflict. Gertrude Bell wrote, in the 1920s: "Until a couple of years ago the Yezidis were ceaselessly at war with the Arabs and with everybody else."[9]

Islamic State conflict

In August 2014, an estimated 40,000[12] to 50,000[13] Yazidis fled to the mountains following raids by Islamic State (IS) forces on the city of Sinjar, which fell to ISIL on August 3.[14] The Yazidi refugees on the mountain faced what a relief worker called a "genocide" by the radicals.[15] Stranded without water, food, shade, or medical supplies, the Yazidis had to rely on scarce[16] supplies of water and food airdropped by American,[17] British,[18] Australian,[19] and Iraqi forces.[20] By August 10, Kurdistan Workers' Party (PKK), People's Protection Units (YPG) and Kurdish Peshmerga forces defended some 30,000 of the Yezidis by opening a corridor from the mountains into nearby Rojava, through the Cezaa and Telkocher road, and from there into Iraqi Kurdistan. [1] [21] although thousands more remained stranded on the mountain as of August 12.[15] It has been reported that 300 Yazidi women were taken as slaves and over 500 men, women, and children were killed, some beheaded or buried alive in the foothills, as part of an effort by the "extremists to instill fear and to supposedly desecrate the mountain the Yazidis consider sacred.[17][21][22] Yezidi girls allegedly raped by ISIS fighters committed suicide by jumping to their death from Mount Sinjar, as described in a witness statement.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ Jabal Sinjār (Approved) at GEOnet Names Server, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

- ↑ جبل سنجار (Native Script) at GEOnet Names Server, United States National Geospatial-Intelligence Agency

- 1 2 Edgell, H. S. 2006. Arabian Deserts: Nature, Origin, and Evolution. Springer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands. 592 pp. ISBN 978-1-4020-3969-0

- 1 2 Numan, N. M. S., and N. K. AI-Azzawi. 2002. Progressive Versus Paroxysmal Alpine Folding in Sinjar Anticline Northwestern Iraq. Iraqi Journal of Earth Science. vol. 2, no.2, pp.59-69.

- ↑ http://rudaw.net/english/middleeast/iraq/20102014

- ↑ http://www.huffingtonpost.com/david-l-phillips/iraqi-kurds-no-friend-but_b_4045389.html

- ↑ Al-Sawaf, F.D.S. 1977. Hydrogeology of South Sinjar Plain Northwest Iraq. Doctoral thesis, University of London

- ↑ Aljubouri, Zeki A.; Aldabbagh, Salim M. (March 1980), "Sinjarite, a new mineral from Iraq" (PDF), Mineralogical Magazine, 43: 643–645, doi:10.1180/minmag.1980.043.329.13

- 1 2 Tim Lister (August 12, 2014). "Dehydration or massacre: Thousands caught in ISIS chokehold". CNN. Retrieved 2014-08-13.

- ↑ Fuccaro, Nelida (1999). The Other Kurds: Yazidis in Colonial Iraq. London: I.B.Tauris. pp. 47–48. ISBN 978-1-86064-170-1.

- ↑ Parry, Oswald Hutton (1895). Six Months in a Syrian Monastery: Being the Record of a Visit to the Head Quarters of the Syrian Church in Mesopotamia: With Some Account of the Yazidis Or Devil Worshippers of Mosul and El Jilwah, Their Sacred Book. London: H. Cox. p. 381. OCLC 3968331.

- ↑ Martin Chulov (3 August 2014). "40,000 Iraqis stranded on mountain as Isis jihadists threaten death". The Guardian. Retrieved 2014-08-06.

- ↑ "Northern Iraq: UN voices concern about civilians' safety, need for humanitarian aid". United Nations News Centre. 2014-08-08. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ↑ "Irak : la ville de Sinjar tombe aux mains de l'Etat islamique" (in French). Le Monde. 2014-08-03. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- 1 2 "Thousands of Yazidis 'still trapped' on Iraq mountain". BBC News. 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ↑ "People Eating Leaves to Survive on Shingal Mountain, Where Three More Die". Rûdaw.net. 2014-08-07. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- 1 2 "Iraq crisis: No quick fix, Barack Obama warns". BBC News. 2014-08-09. Retrieved 2014-08-09.

- ↑ "Britain's RAF makes second aid drop to Mount Sinjar Iraqis trapped by Isis – video". The Guardian. 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- ↑ "JTF633 supports Herc mercy dash". Media Release. Department of Defence. 22 August 2014. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- ↑ "Irak : les opérations pour sauver les réfugiés yézidis continuent" (in French). Le Monde. 2014-08-12. Retrieved 2014-08-12.

- 1 2 "Irak: les yazidis fuient les atrocités des djihadistes". Le Figaro (in French). 10 August 2014. Archived from the original on 2014-08-11.

- ↑ "Etat islamique en Irak : décapités, crucifiés ou exécutés, les yézidis sont massacrés par les djihadistes" (in French). Atlantico. 9 August 2014. Archived from the original on 11 August 2014.

- ↑ Ahmed, Havidar (14 August 2014). "The Yezidi Exodus, Girls Raped by ISIS Jump to their Death on Mount Shingal". Rudaw Media Network. Retrieved 26 August 2014.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sinjar Mountains. |