Fall of Tenochtitlan

| Siege of Tenochtitlan | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire | |||||||

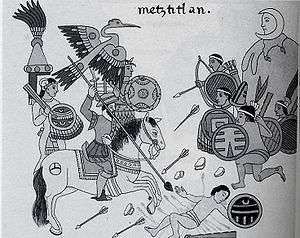

"Conquista de México por Cortés". Unknown artist, second half of the 17th century. Library of Congress, Washington, DC. The depiction of the Aztecs' clothing and weaponry is inaccurate. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Hernán Cortés Gonzalo de Sandoval Pedro de Alvarado Cristóbal de Olid Xicotencatl I Xicotencatl II † | Cuauhtémoc (POW) | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

16 guns[1] 13 brigantines 80,000–200,000 native allies 90–100 cavalry 900–1,300 infantry[1] | 80,000-300,000 warriors[2](including war acallis) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

450–860 Spanish[1] 20,000 Tlaxcallan |

100,000 warriors 100,000 civilians | ||||||

The Siege of Tenochtitlan, the capital of the Aztec Empire, was a decisive event in the Spanish conquest of Mexico. It occurred in 1521 following extensive manipulation of local factions and exploitation of preexisting divisions by Spanish conquistador Hernán Cortés, who was aided by the support of his indigenous allies and his interpreter and companion Malinche.

Although numerous battles were fought between the Aztec Empire and the Spanish-led coalition, which was itself composed primarily of indigenous (mostly Tlaxcaltec) personnel, it was the siege of Tenochtitlan—its outcome probably largely determined by the effects of a smallpox epidemic (which devastated the Aztec population and dealt a severe blow to the Aztec leadership while leaving an immune Spanish leadership intact)—that directly led to the downfall of the Aztec civilization and marked the end of the first phase of the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire.

The conquest of Mexico was a critical stage in the Spanish colonization of the Americas. Ultimately, Spain conquered Mexico and thereby gaining substantial access to the Pacific Ocean meant that the Spanish Empire could finally achieve its original oceanic goal of reaching the Asian markets.

Early events

The road to Tenochtitlan

In April 1519 Hernán Cortés, the Chief Magistrate of Santiago, Cuba, came upon the coast of Mexico at a point he called Vera Cruz with 508 soldiers, 100 sailors, and 14 small cannons. Governor Velazquez, the highest Spanish authority in the Americas, called for Cortés to lead an expedition into Mexico after reports from a few previous expeditions to Yucatán caught the interest of the Spanish in Cuba.[3] Velázquez revoked Cortés' right to lead the expedition once he realized that Cortés intended to exceed his mandate and invade the mainland. After Cortés sailed, Velázquez sent an army led by Pánfilo de Narvaez to take him into custody.

But Cortés used the same legal tactic used by Governor Velázquez when he invaded Cuba years before: he created a local government and had himself elected as the magistrate, thus (in theory) making him responsible only to the King of Spain. Cortés followed this tactic when he and his men established the city of Veracruz. An inquiry into Cortés' action was conducted in Spain in 1529 and no action was taken against him.

As he moved inland Cortés came into contact with a number of polities who resented Aztec rule; Cortés clashed with some of these polities, among them the Totonacs and Tlaxcalans. The latter surrounded his army on a hilltop for two agonizing weeks. Bernal Diaz del Castillo wrote that his numerically inferior force probably would not have survived if it were not for Xicotencatl the Elder and his wish to form an alliance with the Spaniards against the Aztecs.[4]

It once was widely believed that the Aztecs first thought Cortés was Quetzalcoatl, a mythical god prophesied to return to Mexico—coincidentally in the same year Cortés landed and from the same direction he came. This is now believed to be an invention of the conquerors, and perhaps natives who wished to rationalize the actions of the Aztec tlatoani, Moctezuma II. Most scholars agree that the Aztecs, especially the inner circle around Moctezuma, were well convinced that Cortés was not a god in any shape or form.[5]

Moctezuma sent a group of noblemen and other emissaries to meet Cortés at Quauhtechcac. These emissaries brought golden jewelry as a gift, which greatly pleased the Spaniards.[6] According to the Florentine Codex, Lib. 12, f.6r., Moctezuma also ordered that his messengers carry the highly symbolic penacho (headdress) of Quetzalcoatl de Tula to Cortés and place it on his person. As news about the strangers reached the capital city, Moctezuma became increasingly fearful and considered fleeing the city but resigned himself to what he considered to be the fate of his people.[7]

Cortés continued on his march towards Tenochtitlan. Before entering the city, on November 8, 1519 Cortés and his troops prepared themselves for battle, armoring themselves and their horses, and arranging themselves in proper military rank. Four horsemen were at the lead of the procession. Behind these horsemen were five more contingents: foot soldiers with iron swords and wooden or leather shields; horsemen in cuirasses, armed with iron lances, swords, and wooden shields; crossbowmen; more horsemen; soldiers armed with arquebuses; lastly, native peoples from Tlaxcalan, Tliliuhquitepec, and Huexotzinco. The indigenous soldiers wore cotton armor and were armed with shields and crossbows; many carried provisions in baskets or bundles while others escorted the cannons on wooden carts.

Cortés' army entered the city on the flower-covered causeway (Iztapalapa) associated with the god Quetzalcoatl. Cortés was amicably received by Moctezuma. The captive woman Malinalli Tenépal, also known as La Malinche or Doña Marina, translated from Nahuatl to Chontal Maya; the Spaniard Gerónimo de Aguilar translated from Chontal Maya to Spanish.

Moctezuma was soon taken hostage on November 14, 1519, as a safety measure by the vastly outnumbered Spanish. According to all eyewitness accounts, Moctezuma initially refused to leave his palace but after a series of threats from and debates with the Spanish captains, and assurances from La Malinche, he agreed to move to the Axayáctal palace with his retinue. The first captain assigned to guard him was Pedro de Alvarado. Other Aztec lords were also detained by the Spanish.[6] The palace was surrounded by over 100 Spanish soldiers in order to prevent any attempt at rescue.[8]

Tensions mount between Aztecs and Spaniards

It is uncertain why Moctezuma cooperated so readily with the Spaniards. It is possible he feared losing his life or political power. It was clear from the beginning that he was ambivalent about who Cortés and his men really were: gods, descendants of a god, ambassadors from a greater king, or just barbaric invaders? From the perspective of the tlatoani, the Spaniards might have been assigned some decisive role by fate. It could also have been a tactical move: Moctezuma may have wanted to gather more information on the Spaniards, or to wait for the end of the agricultural season and strike at the beginning of the war season. However, he did not carry out either of these actions even though high-ranking military leaders such as his brother Cuitlahuac and nephew Cacamatzin urged him to do so.[1]

With Moctezuma captive, Cortés did not need to worry about being cut off from supplies or being attacked, although some of his captains had such concerns. He also assumed that he could control the Aztecs through Moctezuma. However, Cortés had little knowledge of the ruling system of the Aztecs; Moctezuma was not all-powerful as Cortés imagined. Being appointed to and maintaining the position of tlatoani was based on the ability to rule decisively; he could be replaced by another noble if he failed to do so. At any sign of weakness, Aztec nobles within Tenochtitlan and in other Aztec tributaries were liable to rebel. As Moctezuma complied with orders issued by Cortés, such as commanding tribute to be gathered and given to the Spaniards, his authority was slipping, and quickly his people began to turn against him.[1]

Cortés and his army were permitted to stay in the Palace of Axayacatl, and tensions continued to grow. While the Spaniards were in Tenochtitlan, Velazquez assembled a force of nineteen ships, more than 800 soldiers, twenty cannons, eighty horsemen, one-hundred and twenty crossbowmen, and eighty arquebusiers under the command of Pánfilo de Narvaez to capture Cortés and return him to Cuba. Velazquez felt that Cortés had exceeded his authority, and had been aware of Cortés's misconduct for nearly a year. He had to wait for favorable winds, though, and was unable to send any forces until spring. Narvaez’s troops landed at San Juan de Ulúa on the Mexican coast around April 20, 1520.[9]

After Cortés became aware of their arrival, he brought a small force of about two hundred and forty to Narvaez’s camp in Cempohuallan on May 27. Cortés attacked Narvaez’s camp late at night. His men wounded Narvaez and took him as a hostage quickly. Evidence suggests that the two were in the midst of negotiations at the time, and Narvaez was not expecting an attack. Cortés had also won over Narvaez’s captains with promises of the vast wealth in Tenochtitlan, inducing them to follow him back to the Aztec capital. Narvaez was imprisoned in Vera Cruz, and his army was integrated into Cortés’s forces.[1]

Rapid deterioration of relations

Massacre at the festival of Tóxcatl

During Cortés’s absence, Pedro de Alvarado was left in command in Tenochtitlan with 120 soldiers.[10]

At this time, the Aztecs began to prepare for the annual festival of Toxcatl in early May, in honor of Tezcatlipoca, otherwise known as the Smoking Mirror or the Omnipotent Power. They honored this god during the onset of the dry season so that the god would fill dry streambeds and cause rain to fall on crops. Moctezuma secured the consent of Cortés to hold the festival, and again confirmed permission with Alvarado.[11]

Alvarado agreed to allow the festival on the condition that there would be no human sacrifice but the Toxcatl festival had featured human sacrifice as the main part of its climactic rituals. The sacrifice involved the killing of a young man who had been impersonating the god Toxcatl deity for a full year. Thus, prohibiting human sacrifice during this festival was an untenable proposition for the Aztecs.

Before the festival, Alvarado encountered a group of women building a statue of Huitzilopochtli and the image unsettled him, and he became suspicious about the eventuality of human sacrifice. He tortured priests and nobles and discovered that the Aztecs were planning a revolt. Unable to assert control over events, he sequestered Moctezuma and increased the guards around the tlatoani.[12]

By the day of the festival, the Aztecs had gathered on the Patio of Dances. Alvarado had sixty of his men as well as many of his Tlaxcalan allies into positions around the patio. The Aztecs initiated the Serpent Dance. The euphoric dancing as well as the accompanying flute and drum playing disturbed Alvarado about the potential for revolt. He ordered the gates closed and initiated the killing of many thousands of Aztec nobles, warriors and priests.[13]

Alvarado, the conquistadors and the Tlaxcalans retreated to their base in the Palace of Axayacatl and secured the entrances. Alvarado ordered his men to shoot their cannons, crossbows and arquebuses into the gathering crowd. The Aztec revolt became more widespread as a result. Alvarado forced Moctezuma to appeal to the crowd outside the Palace and this appeal temporarily calmed them.[14]

The massacre had the result of resolutely turning all the Aztecs against the Spanish and completely undermining Moctezuma's authority.[15]

Aztec revolt

When it became more clear what was happening to the Aztecs outside the Temple, the alarm was sounded. Aztec warriors came running, and fired darts and launched spears at the Spanish forces.[6] This may have been due to the fact that their military infrastructure was severely damaged after the attack on the festival, as the most elite seasoned warriors were killed.[1]

Alvarado sent for word to Cortés of the events, and Cortés hurried back to Tenochtitlan on June 24 with 1,300 soldiers, 96 horses, 80 crossbowmen, and 80 arquebusiers. Cortés also came with 2,000 Tlaxcalan warriors on the journey.[1] Cortés entered the palace unscathed, although the Aztecs had probably planned to ambush him. The Aztecs had already stopped sending food and supplies to the Spaniards. They became suspicious and watched for people trying to sneak supplies to them; many innocent people were slaughtered because they were suspected of helping them.[16] The roads were shut and the causeway bridges were raised. The Aztecs halted any Spanish attacks or attempts to leave the palace. Every Spanish soldier that was not killed was wounded.[1]

Cortés failed to grasp the full extent of the situation, as the attack on the festival was the last straw for the Aztecs, who now were completely against Moctezuma and the Spanish. Thus, the military gains of the attack also had a serious political cost for Cortés.[1]

Cortés attempted to parley with the Aztecs, and after this failed he sent Moctezuma to tell his people to stop fighting. However, the Aztecs refused.[16] The Spanish asserted that Moctezuma was stoned to death by his own people as he attempted to speak with them.[17] The Aztecs later claimed that Moctezuma was murdered by the Spanish.[1][1][16] Two other local rulers were found strangled as well.[18] Moctezuma’s younger brother Cuitláhuac, who had been ruler of Ixtlapalapan until then, was chosen as the Tlatoani.[1]

La Noche Triste and the Spanish flight to Tlaxcala

This Aztec victory is still remembered as “La Noche Triste,” The Night of Sorrows. Popular tales say that Cortés wept under a tree the night of the massacre of his troops at the hands of the Aztecs.

Though a flight from the city would make Cortés appear weak before his indigenous allies, it was this or death for the Spanish forces. Cortés and his men were in the center of the city, and would most likely have to fight their way out no matter what direction they took. Cortés wanted to flee to Tlaxcala, so a path directly east would have been most favorable. Nevertheless, this would require hundreds of canoes to move all of Cortés’s people and supplies, which he was unable to procure in his position.[1]

Thus, Cortés had to choose among three land routes: north to Tlatelolco, which was the least dangerous path but required the longest trip through the city; south to Coyohuacan and Ixtlapalapan, two towns that would not welcome the Spanish; or west to Tlacopan, which required the shortest trip through Tenochtitlan, though they would not be welcome there either. Cortés decided on the west causeway to Tlacopan, needing the quickest route out of Tenochtitlan with all his provisions and people.[1]

Heavy rains and a moonless night provided some cover for the escaping Spanish.[18] On that "Sad Night," July 1, 1520, the Spanish forces exited the palace first with their indigenous allies close behind, bringing as much treasure as possible. Cortés had hoped to go undetected by muffling the horses’ hooves and carrying wooden boards to cross the canals. The Spanish forces were able to pass through the first three canals, the Tecpantzinco, Tzapotlan, and Atenchicalco.[16]

However, they were discovered on the fourth canal at Mixcoatechialtitlan. One account says a woman fetching water saw them and alerted the city, another says it was a sentry. Some Aztecs set out in canoes, others by road to Nonchualco then Tlacopan to cut the Spanish off. The Aztecs attacked the fleeing Spanish on the Tlacopan causeway from canoes, shooting arrows at them. The Spanish fired their crossbows and arquebuses, but were unable to see their attackers or get into formation. Many Spaniards leaped into the water and drowned, weighed down by armor and booty.[16]

When faced with a gap in the causeway, Alvarado made the famous “leap of Alvarado” using a spear to get to the other side. Approximately a third of the Spaniards succeeding in reaching the mainland, while the remaining ones died in battle or were captured and later sacrificed on Aztec altars. After crossing over the bridge, the surviving Spanish had little reprieve before the Aztecs appeared to attack and chase them towards Tlacopan. When they arrived at Tlacopan, a good number of Spanish had been killed, as well as most of the indigenous warriors, and some of the horses; all of the cannons and most of the crossbows were lost.[1] The Spanish finally found refuge in Otancalpolco, where they were aided by the Teocalhueyacans. The morning after, the Aztecs returned to recover the spoils from the canals.[16]

To reach Tlaxcala, Cortés had to bring his troops around Lake Texcoco. Though the Spanish were under attack the entire trip, because Cortés took his troops through the northern towns, they were at an advantage. The northern valley was less populous, travel was difficult, and it was still the agricultural season, so the attacks on Cortés’s forces were not very heavy. As Cortés arrived in more densely inhabited areas east of the lake, the attacks were more forceful.[1]

Battle of Otumba

Before reaching Tlaxcala, the scanty Spanish forces arrived at the plain of Otumba Valley (Otompan), where they were met by a vast Aztec army intent on their destruction. The Aztecs intended to cut short the Spanish retreat from Tenochtitlan. The Aztecs had underestimated the shock value of the Spanish caballeros because all they had seen was the horses traveling on the wet paved streets of Tenochtitlan. They had never seen them used in open battle on the plains.[18]

Despite the overwhelming numbers of Aztecs and the generally poor condition of the Spanish survivors, Cortés snatched victory from the jaws of defeat when he spotted the Aztec commander in his ornate and colourful feather costume, and immediately charged him with several horsemen, killing the Aztec commander. There were heavy losses for the Spanish, but in the end they were victorious. The Aztecs retreated.[18]

When Cortés finally reached Tlaxcala five days after fleeing Tenochtitlan, he had lost over 860 Spanish soldiers, over a thousand Tlaxcalans, as well as Spanish women who had accompanied Narvaez's troop.[1] Cortés claimed only 15 Spaniards were lost along with 2,000 native allies. Cano, another primary source, gives 1150 Spaniards dead, though this figure was most likely more than the total number of Spanish. Francisco López de Gómara, Cortés' chaplain, estimated 450 Spaniards and 4,000 allies had died. Other sources estimate that nearly half of the Spanish and almost all of the natives were killed or wounded.[18]

The women survivors included Cortés's translator and lover La Malinche, María Estrada, and two of Moctezuma's daughters who had been given to Cortés, including the emperor's favorite and reportedly most beautiful daughter Tecuichpotzin (later Doña Isabel Moctezuma). A third daughter died, leaving behind her infant by Cortés, the mysterious second "María" named in his will.

Both sides attempt to recover

Shifting alliances

Cuitláhuac had been elected as the emperor immediately following Moctezuma’s death. It was necessary for him to prove his power and authority to keep the tributaries from revolting. Usually, the new king would take his army on a campaign before coronation; this demonstration would solidify necessary ties. However, Cuitláhuac was not in a position to do this, as it was not yet war season; therefore, allegiance to the Spanish seemed to be an option for many tributaries. The Aztec empire was very susceptible to division: most of the tributary states were divided internally, and their loyalty to the Aztecs was based either on their own interests or fear of punishment.

It was necessary for Cortés to rebuild his alliances after his escape from Tenochtitlan before he could try again to take the city. He started with the Tlaxcalans. Tlaxcala was an autonomous state, and a fierce enemy of the Aztecs. Another strong motivation to join forces with the Spanish was that Tlaxcala was encircled by Aztec tributaries. The Tlaxcalans could have crushed the Spaniards at this point or turned them over to the Aztecs. In fact, the Aztecs sent emissaries promising peace and prosperity if they would do just that. The Tlaxcalan leaders rebuffed the overtures of the Aztec emissaries, deciding to continue their friendship with Cortés.

Cortés managed to negotiate an alliance; however, the Tlaxcalans required heavy concessions from Cortés for their continued support, which he was to provide after they defeated the Aztecs. They expected the Spanish to pay for their supplies, to have the city of Cholula, an equal share of any of the spoils, the right to build a citadel in Tenochtitlan, and finally, to be exempted from any future tribute. Cortés was willing to promise anything in the name of the King of Spain, and agreed to their demands. The Spanish did complain about having to pay for their food and water with their gold and other jewels with which they had escaped Tenochtitlan. The Spanish authorities would later disown this treaty with the Tlaxcalans after the fall of Tenochtitlan.

Cortés needed to gain new alliances as well. The Spaniards needed to be able to prove they could protect new allies from the possibility of Aztec retribution, changing sides would not be too difficult for other tributaries. Additionally Cortés’s forces managed to defeat the smaller armies of some of the tributary states. Once Cortés had demonstrated his political power, states such as Tepeyac, and later Yauhtepec and Cuauhnahuac, were easily won over. Cortés also used political maneuvering to assure the allegiance of other states, such as Tetzcoco. In addition, Cortés replaced kings with those who he knew would be loyal to him. Cortés now controlled many major towns, which simultaneously bolstered Cortés’s forces while weakening the Aztecs.[1]

Though the largest group of indigenous allies were Tlaxcalans, the Huexotzinco, Atlixco, Tliliuhqui-Tepecs, Tetzcocans, Chalca, Alcohua and Tepanecs were all important allies as well, and had all been previously subjugated by the Aztecs.[1][18]

Even the former Triple Alliance member, city of Tetzcoco (or Texcoco) became a Spanish ally. As the rebellion attempt led by the Tetzcocan Tlatoani, Cacamatzin in times of Moctezuma's reclusion was conjured by the Spanish,[19] Cortés named one of Cacamatzin's brothers as new tlatoani. He was Ixtlilxóchitl II, who had disagreed with his brother and always proved friendly to the Spanish. Later, Cortés also occupied the city as base for the construction of brigantines. However, one faction of Tetzcocan warriors remain loyal to the Aztecs.[20]

Cortés had to put down internal struggles among the Spanish troops as well. The remaining Spanish soldiers were somewhat divided; many wanted nothing more than to go home, or at the very least to return to Vera Cruz and wait for reinforcements. Cortés hurriedly quashed this faction, determined to finish what he started. Not only had he staked everything he had or could borrow on this enterprise, he had completely compromised himself by defying his superior Velazquez. He knew that in defeat he would be considered a traitor to Spain, but that in success he would be its hero. So he argued, cajoled, bullied and coerced his troops, and they began preparing for the siege of Mexico. In this Cortés showed skill at exploiting the divisions within and between the Aztec states while hiding those of his own troops.[1]

Smallpox reduces the local population

While Cortés was rebuilding his alliances and garnering more supplies, a smallpox epidemic struck the natives of the Valley of Mexico, including Tenochtitlan. The disease was probably carried by a Spanish slave from Narvaez’s forces, who had been abandoned in the capital during the Spanish flight.[1] Smallpox played a crucial role in the Spanish success during the Siege of Tenochtitlan from 1519–1521, a fact not mentioned in some historical accounts. The disease broke out in Tenochtitlan in late October 1520. The epidemic lasted sixty days, ending by early December.[21]

It was at this event where firsthand accounts were recorded in the Florentine Codex concerning the adverse effects of the smallpox epidemic of the Aztecs, which stated, “many died from this plague, and many others died of hunger. They could not get up and search for food, and everyone else was too sick to care for them, so they starved to death in their beds. By the time the danger was recognized, the plague was well established that nothing could halt it”.[21] The smallpox epidemic caused not only infection to the Mexica peoples, but it weakened able bodied people who could no longer grow and harvest their crops, which in turn led to mass famine and death from malnutrition.[21] While the population of Tenochtitlan was recovering, the disease continued to Chalco, a city on the southeast corner of Lake Texcoco that was formerly controlled by the Aztecs but now occupied by the Spanish.[6]

Reproduction and population growth declined since people of child bearing age either had to fight off the Spanish invasion or died due to famine, malnutrition or other diseases.[22] Diseases like smallpox could travel great distances and spread throughout large populations, which was the case with the Aztecs having lost approximately 50% of its population from smallpox and other diseases.[23] The disease killed an estimated forty percent of the native population in the area within a year. The Aztecs codices give ample depictions of the disease's progression. It was known to them as the huey ahuizotl (great rash).

Cuitlahuac contracted the disease and died after ruling for eighty days. Though the disease drastically decreased the numbers of warriors on both sides, it had more dire consequences for the leadership on the side of the Aztecs, as they were much harder hit by the smallpox than the Spanish leaders, who were largely resistant to the disease.

Aztecs regroup

It is often debated why the Aztecs took little action against the Spanish and their allies after they fled the city. One reason was that Tenochtitlan was certainly in a state of disorder: the smallpox disease ravaged the population, killing still more important leaders and nobles, and a new king, Cuauhtémoc, son of King Ahuitzotl, was placed on the throne in February 1521. The people were in the process of mourning the dead and rebuilding their damaged city. It is possible that the Aztecs truly believed that the Spanish were gone for good.[1]

Staying within Tenochtitlan as a defensive tactic may have seemed like a reliable strategy at the time. This would allow them the largest possible army that would be close to its supplies, while affording them the mobility provided by the surrounding lake. Any Spanish assault would have to come through the causeways, where the Aztecs could easily attack them.[1]

Siege of Tenochtitlan

Cortés plans and prepares

Cortés’s overall plan was to trap and besiege the Aztecs within their capital. Cortés intended to do that primarily by increasing his power and mobility on the lake, while protecting "his flanks while they marched up the causeway", previously one of his main weaknesses. He ordered the construction of thirteen sloops (brigantines) in Tlascala, by his master shipbuilder, Martín López. Cortés continued to receive a steady stream of supplies from ships arriving at Vera Cruz, one ship from Spain loaded with "arms and powder", and two ships intended for Narvaez. Cortes also received one hundred and fifty soldiers and twenty horses from the abandoned Panuco river settlement.[24]:309,311,324

Cortés then decided to move his army to Tetzcoco, where he could assemble and launch the sloops in the creeks flowing into Lake Texcoco. With his main headquarters in Tetzcoco, he could stop his forces from being spread too thin around the lake, and there he could contact them where they needed. Xicotencatl the Elder provided Cortes with ten thousand plus Tlascalan warriors under the command of Chichimecatecle. Cortes departed Tlascala on the day after Christmas 1520. When his force arrived at the outskirts of Tetzcoco, he was met by seven chieftains stating their leader Coanacotzin begs "for your friendship". Cortes quickly replaced that leader with the son of Nezahualpilli, baptized as Don Hernando Cortes.[24]:311–316

After winning over Chalco and Tlamanalco, Cortes sent eight Mexican prisoners to Guatemoc stating, "all the towns in the neighbourhood were now on our side, as well as the Tlascans". Cortes intended to blockade Mexico and then destroy it. Once Martin Lopez and Chichimecatecle brought the logs and planks to Texcoco, the sloops were built quickly.[24]:321–325 Guatemoc's forces were defeated four times in March 1521, around Chalco and Huaxtepec, and Cortes received another ship load of arms and men from the Emperor.[24]:326–332

On 6 April 1521, Cortes met with the Caciques around Chalco, and announced he would "bring peace" and blockade Mexico. He wanted all of their warriors ready the next day when he put thirteen launches into the lake. He was then joined at Chimaluacan by twenty thousand warriors from Chalco, Texcoco, Huexotzingo, and Tlascala.[24]:333 Cortes fought a major engagement with seventeen thousand Guatemoc warriors at Xochimilco, before continuing his march northwestward.[24]:340–347 Cortes found Coyoacan, Tacuba, Atzcapotzalco, and Cuauhitlan deserted.[24]:347–349

Returning to Texcoco, which had been guarded by his Captain Gonzalo de Sandoval, Cortes was joined by many more men from Castile.[24]:349 Cortes then discovered a plot aimed at his murder, for which he had the main conspirator, Antonio de Villafana, hanged. Thereafter, Cortes had a personal guard of six soldiers, under the command of Antonio de Quinones.[24]:350–351 The Spaniards also held their third auctioning of branded slaves, Mexican allies captured by Cortes, "who had revolted after giving their obedience to His Majesty."[24]:308,352

Cortés had 84 horsemen, 194 arbalesters and arquebusiers, plus 650 Spanish foot soldiers. He stationed 25 men on every launch, 12 oarsmen, 12 crossbowmen and musketeers, and a captain. Each launch had rigging, sails, oars, and spare oars. Additionally, Cortes had 20,000 warriors from Tlascala, Huexotzinco, and Cholula. The Tlascalans were led by Xicotencatl II and Chichimecatecle. Cortes was ready to start the blockade of Mexico after Corpus Christi (feast).[24]:353–354

Cortés put Alvarado in command of 30 horsemen, 18 arbalesters and arquebusiers, 150 Spanish foot soldiers, and 8,000 Tlaxcalan allies, and sent him, accompanied by his brother Jorge de Alvarado, Gutierrez de Badajoz, and Andres de Monjaraz, to secure Tacuba. Cristobal de Olid took 30 horsemen, 20 arbalesters and arquebusiers, 175 foot soldiers, and 8,000 Tlaxcalan allies, accompanied by Andres de Tapia, Francisco Verdugo, and Francisco de Lugo, and secured Coyohuacan. Gonzalo de Sandoval took 24 horsemen, 14 arquebusiers and arbalesters, 150 Spanish foot soldiers, and 8,000 warriors from Chalco and Huexotzinco, accompanied by Luis Marin and Pedro de Ircio, to secure Ixtlapalapan. Cortes commanded the 13 launches.[24]:356 Cortés' forces took up these positions on May 22.[1]

The first battles

The forces under Alvarado and Olid marched first towards Chapultepec to disconnect the Aztecs from their water supply.[24]:359 There were springs there that supplied much of the city’s water by aqueduct; the rest of the city’s water was brought in by canoe. The two generals then tried to bring their forces over the causeway at Tlacopan, resulting in the Battle of Tlacopan.[1] The Aztec forces managed to push back the Spanish and halt this assault on the capital with a determined and hard fought land and naval counterattack.[16]:94[24]:359–360

Cortes faced "more than a thousand canoes" after he launched his thirteen launches from Texcoco. Yet a "favorable breeze sprang up", enabling him to overturn many canoes and kill or capture many. After winning the First Battle on the Lake, Cortes camped with Olid's forces.[16]:94[24]:362

The Aztec canoe fleets worked well for attacking the Spanish because they allowed the Aztecs to surround the Spanish on both sides of the causeway. Cortés decided to make an opening in the causeway so that his brigantines could help defend his forces from both sides. He then distributed the launches amongst his attacking forces, four to Alvarado, six for Olid, and two to Sandoval on the Tepeaquilla causeway. After this move, the Aztecs could no longer attack from their canoes on the opposite side of the Spanish brigantines, and "the fighting went very much in our favour", according to Diaz.[24]:363

With his brigantines, Cortés could also send forces and supplies to areas he previously could not, which put a kink in Cuauhtémoc's plan. To make it more difficult for the Spanish ships to aid the Spanish soldier's advance along the causeways, the Aztecs dug deep pits in shallow areas of the lakes, into which they hoped the Spaniards would stumble, and fixed concealed stakes into the lake bottom to impale the launches. The Spanish horses were also ineffective on the causeways.[24]:364

Cortés was forced to adapt his plans again, as his initial land campaigns were ineffective. He had planned to attack on the causeways during the daytime and retreat to camp at night; however, the Aztecs moved in to occupy the abandoned bridges and barricades as soon as the Spanish forces left. Consequently, Cortés had his forces set up on the causeways at night to defend their positions.[24]:364–366 Cortes also sent orders to "never on any account to leave a gap unblocked, and that all the horsemen were to sleep on the causeway with their horses saddled and bridled all night long."[24]:372 This allowed the Spanish to progress closer and closer towards the city.[1]

The Spaniards prevented food and water from reaching Tenochtitlan along the three causeways. They limited the supplies reaching the city from the nine surrounding towns via canoe, by sending out two of their launches on nightly capture missions. However, the Aztecs were successful in setting an ambush with thirty of their pirogues in an area in which they had placed impaling stakes. They captured two Spanish launches, killing Captain de Portilla and Pedro Barba.[24]:368–369,382–383

The Spanish advance closer

After capturing two chieftains, Cortes learned of another Aztec plot to ambush his launches with forty pirogues. Cortes then organized a counter-ambush with six of his launches, which was successful, "killing many warriors and taking many prisoners." Afterwards, the Mexicans "did not dare to lay any more ambuscades, or to bring in food and water as openly as before." Lakeside towns, including Iztapalapa, Churubusco, Culuacan, and Mixquic made peace with the Spaniards.[24]:374–375 The fighting in Tenochtitlan was described by the American historian Charles Robinson as "desperate" as both sides battled one another in the streets in a ferocious battle where no quarter was given nor asked for.[25]

Guatemoc then attacked all three Spanish camps simultaneously with his entire army on the feast day of St. John. On the Tacuba Causeway across Lake Texcoco connecting Tenochtitlan to the mainland along a street now known as Puente de Alvarado (Alvarado's Bridge) in Mexico City, Pedro de Alvarado made a mad cavalry charge across a gap in the Causeway.[26] As Alvardo and his cavalry emerged on the other side of the gap with the infantry behind, Aztec canoes filled the gap.[27] Pedro de Alvarado was wounded along with eight men in his camp.[24]:377 Alvarado escaped from the ambush, but five of his men were captured and taken off to the Great Temple to be sacrificed.[28] Much to their horror, the Spanish from their positions could see their captured comrades being sacrificed on the Great Pyramid, which increased their hatred of the Aztecs.[29] At the end of each day, the Spanish gave a prayer: "Oh, thanks be to God that they did not carry me off today to be sacrificed."[30]

Cortes then decided to push forward a simultaneous attack towards the Mexican market square. However, he neglected to fill in a channel as he advanced, and when the Mexicans counter-attacked, Cortes was wounded and almost captured. Cristobal de Olea and Cristobal de Guzman gave their lives for Cortes, and sixty-five Spanish soldiers were captured alive. Guatemoc then had five of their heads thrown at Alvarado's camp, four thrown at Cortes' camp, six thrown at Sandoval's camp, while ten more were sacrificed to the Huichilobos and Texcatlipoca idols.[24]:379–383

Diaz relates, "...the dismal drum of Huichilobos sounded again,...we saw our comrades who had been captured in Cortes' defeat being dragged up the steps to be sacrificed...cutting open their chests, drew out their palpitating hearts which they offered to the idols...the Indian butchers...cut off their arms and legs...then they ate their flesh with a sauce of peppers and tomatoes...throwing their trunks and entrails to the lions and tigers and serpents and snakes." Guatemoc then "sent the hands and feet of our soldiers, and the skin of their faces...to all the towns of our allies..." The Mexicans sacrificed a batch of Spanish prisoners each night for ten nights.[24]:386–387,391 The Mexicans cast off the cooked limbs of their prisoners to the Tlaxcalans, shouting: "Eat the flesh of these tueles ["Gods"-a reference to the early belief that Spanish were gods] and of your brothers because we are sated with it".[31]

The Mexicans continued to attack the Spaniards on the causeways, "day and night". The Spanish allies in the cities surrounding the lake lost many lives or "went home wounded", and "half their canoes were destroyed". Yet, "they did not help the Mexicans any more, for they loathed them." Yet, of the 24,000 thousand allies, only 200 remained in the three Spanish camps, the rest deciding to return home. Ahuaxpitzactzin (later baptized as Don Carlos), the brother of the Texcoco lord Don Fernando, remained in Cortes' camp with forty relatives and friends. The Huexotzinco Cacique remained in Sandoval's camp with fifty men. Alvarado's camp had Chichimecatecle, the two sons of Lorenzo de Vargas, and eighty Tlascalans.[24]:388–389 To maintain the advance, Cortés razed every neighborhood he captured, using the rubble to fill up canals and gaps in the causeways to allow his infantry and cavalry to advance in formation, a fighting tactic that favored the Spanish instead of engaging in hand to hand street fighting, which favored the Mexicans.[32]

Cortes then concentrated on letting the Mexicans "eat up all the provisions they have" and drink brackish water. The Spaniards gradually advanced along the causeways, though without allies. Their launches had freedom of the lake, after devising a method for breaking the impaling stakes the Mexicans had placed for them. After twelve days of this, the Spanish allies realized the prophesy by the Aztec idols, that the Spaniards would be dead in ten days was false. Two thousand warriors returned from Texcoco, as did many Tlascan warriors under Tepaneca from Topeyanco, and those from Huexotzingo and Cholula.[24]:390–391

Guatemoc then enlisted his allies in Matlazingo, Malinalco, and Tulapa, in attacking the Spaniards from the rear. However, Cortes sent Andres de Tapia, with 20 horsemen and 100 soldiers, and Gonzalo de Sandoval, with 20 horsemen and 80 soldiers, to help his allies attack this new threat. They returned with two of the Matlazingo chieftains as prisoners.[24]:396

As the Spanish employed more successful strategies, their stranglehold on Tenochtitlan tightened, and famine began to affect the Aztecs. The Aztecs were cut off from the mainland because of the occupied causeways. Cortés also had the advantage of fighting a mostly defensive battle. Though Cuauhtémoc organized a large-scale attack on Alvarado’s forces at Tlacopan, the Aztec forces were pushed back. Throughout the siege, the Aztecs had little aid from outside of Tenochtitlan. The remaining loyal tributaries had difficulty sending forces, because it would leave them vulnerable to Spanish attack. Many of these loyal tributaries were surrounded by the Spanish.

Though the tributaries often went back and forth in their loyalties at any sign of change, the Spanish tried hard not to lose any allies. They feared a “snowball effect,” in that if one tributary left, others might follow. Thus, they brutally crushed any tributaries who tried to send help to Tenochtitlan. Any shipments of food and water were intercepted, and even those trying to fish in the lake were attacked.[1] The situation inside the city was desperate: because of the famine and the smallpox there were already thousands of victims, women offered to the gods even their children' clothes, so most children were stark naked. Many Aztecs drank dirty, brackish water because of their severe thirst and contracted dysentery. The famine was so severe that the Aztecs ate anything, even wood, leather, and bricks for sustenance.[6]

The Spanish continued to push closer to Tenochtitlan. The Aztecs changed tactics as often as the Spanish did, preventing Cortés’s forces from being entirely victorious. However, the Aztecs were severely worn down. They had no new troops, supplies, food, nor water. The Spanish received a large amount of supplies from Vera Cruz, and, somewhat renewed, finally entered the main part of Tenochtitlan.[1][24]:396

The Aztecs' last stand

Cortes then ordered a simultaneous advance of all three camps towards the Tlatelolco marketplace. Alvarado's company made it there first, and Gutierrez de Badajoz advanced to the top of the Huichilcbos cue, setting it afire and planting their Spanish banners. Cortes' and Sandoval's men were able to join them there after four more days of fighting.[24]:396–398

The Spanish forces and their allies advanced into the city. Despite inflicting heavy casualties, the Aztecs could not halt the Spanish advance. While the fighting in the city raged, the Aztecs cut out and eaten the hearts of 70 Spanish prisoners-of-war at the altar at Huitzilopochtli. By August, many of the native inhabitants had fled Tlatelolco.[16] Cortés sent emissaries to negotiate with the Tlatelolcas to join his side, but the Tlatelolcas remained loyal to the Aztecs. Throughout the siege, the Tlaxcalans waged a merciless campaign against the Aztecs who had long oppressed them as for hundreds of years the Tlaxcalans had been forced to hand over an annual quota of young men and women to be sacrificed and eaten at the Great Pyramid of Tenochtitlan, and now the Tlaxcalans saw their chance for revenge.[33] The American historian Charles Robinson wrote: "Centuries of hate and the basic viciousness of Mesoamerican warfare combined in violence that appalled Cortés himself".[34] In letter to the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, Cortés wrote:

"We had more trouble in preventing our allies from killing with such cruelty than we had in fighting the enemy. For no race, however savage, has ever practiced such fierce and unnatural cruelty as the natives of these parts. Our allies also took many spoils that day, which we were unable to prevent, as they numbered more than 150, 000 and we Spaniards only some nine hundred. Neither our precautions nor our warnings could stop their looting, though we did all we could...I had posted Spaniards in every street, so that when the people began to come out [to surrender] they might prevent our allies from killing those wretched people, whose numbers was uncountable. I also told the captains of our allies that on no account should any of those people be slain; but there were so many that we could not prevent more than fifteen thousand being killed and sacrificed [by the Tlaxcalans] that day".[35]

Throughout the battles with the Spanish, the Aztecs still practiced the traditional ceremonies and customs. Tlapaltecatl Opochtzin was chosen to be outfitted to wear the quetzal owl costume. He was supplied with darts sacred to Huitzilopochtli, which came with wooden tips and flint tops. When he came, the Spanish soldiers appeared scared and intimidated. They chased the owl-warrior, but he was neither captured nor killed. The Aztecs took this as a good sign, but they could fight no more, and after discussions with the nobles, Cuauhtémoc began talks with the Spanish.[6]

After several failed peace overtures to Guatemoc, Cortes ordered Sandoval to attack that part of the city in which Guatemoc had retreated. As hundreds of canoes filled the lake fleeing the doomed city, Cortés his brigantines out to intercept them.[36] Guatemoc attempted to flee with his property, gold, jewels, and family in fifty pirogues, but was soon captured by Sandoval's launches, and brought before Cortes.[24]:401–403

The surrender

The Aztec forces were destroyed and the Aztecs surrendered on 13 August 1521.[24]:404 Cortés demanded the return of the gold lost during La Noche Triste. Under torture, by burning their feet with oil, Cuauhtémoc and the lord of Tacuba, confessed to dumping his gold and jewels into the lake. Yet, little gold remained, as earlier, a fifth had been sent to Spain and another kept by Cortés. "In the end...the remaining gold all fell to the King's officials."[24]:409–410,412

Cuauhtémoc was taken hostage the same day and remained the titular leader of Tenochtitlan, under the control of Cortés, until he was hanged for treason in 1525 while accompanying a Spanish expedition to Guatemala.

Remaining Aztec warriors and civilians fled the city as the Spanish forces, primarily the Tlaxcalans, continued to attack even after the surrender, slaughtering thousands of the remaining civilians and looting the city. The Spanish and Tlaxcalans did not spare women or children: they entered houses, stealing all precious things they found, raping and then killing women, stabbing children.[16] The survivors marched out of the city for the next three days.[1]

Almost all of the nobility were dead, and the remaining survivors were mostly young women and very young children.[18] It is difficult, if not impossible, to determine with any exactitude the number of people killed during the siege. As many as 240,000 Aztecs are estimated to have died, according to the Florentine Codex, during the eighty days. This estimate is greater, however, than some estimates of the entire population (60,000–300,000) even before the smallpox epidemic of 1520. Reasonable Spanish observers estimated that approximately 100,000 inhabitants of the city died from all causes.

Although some reports put the number as low as forty, the Spanish probably lost around 100 soldiers in the siege, while thousands of Tlaxcalans perished. It is estimated that around 1,800 Spaniards died from all causes during the two-year campaign—from Vera Cruz to Tenochtitlan. (Thomas, p. 528-9) The remaining Spanish forces consisted of 800–900 Spaniards, eighty horses, sixteen pieces of artillery, and Cortés’s thirteen brigantines.[1] Other sources estimate that around 860 Spanish soldiers and 20.000 Tlaxcalan warriors were killed during all the battles in this region from 1519–1521.

It is well accepted that Cortés’ indigenous allies, which may have numbered as many as 200,000 over the three-year period of the "conquest," were indispensable to his success. Their support was not acknowledged until much later, and they derived little benefit from their sacrifices, aside from being rid of the Aztecs. Although several major, allied native groups emerged from this campaign, none were willing to challenge the Spaniards, and the person who benefited was Cortés, who ruled the remnants of the Aztec Empire through his captive and puppet, Cuauhtėmoc and other Aztec lords.[4]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Hassig, Ross. Mexico and the Spanish Conquest. New York: Longman, 1994.

- ↑ George Edwin Mueller

- ↑ Conquistadors, with Michael Wood – website for 2001 PBS documentary

- 1 2 Black, Jeremy, ed. World History Atlas. London: Dorling Kindersley, 2000.

- ↑ "The Mexico Reader: History, Culture, Politics". Joseph, Gilbert M. and Henderson, Timothy J. Duke University Press, 2002.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "General History of The Things of New Spain." de Sahagun, Bernardino. The Human Record: Sources of Global History, Volume II. Andrea, Alfred J. and James H. Overfield. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005. 128–33.

- ↑ "Visión de los vencidos." León-Portilla, Miguel (Ed.) [1959] (1992). The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico, Ángel María Garibay K. (Nahuatl-Spanish trans.), Lysander Kemp (Spanish-English trans.), Alberto Beltran (illus.), Expanded and updated edition, Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-5501-8.

- ↑ Cervantes de Salazar, Francisco. "Crónica de la Nueva España. Madrid: Linkgua Ediciones, 2007.

- ↑ Hassig (2006, p.107).

- ↑ Thomas, Hugh.Conquest: Montezuma, Cortes, and the Fall of Old Mexico, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1993), 369. Levy, Buddy, Conquistador: Hernan Cortes, King Montezuma, and the Last Stands of the Aztecs, (New York: Bantam Books, 2008), 120.

- ↑ Levy, Buddy, Conquistador: Hernan Cortes, King Montezuma, and the Last Stands of the Aztecs, (New York: Bantam Books, 2008), 163–164.

- ↑ Levy, Buddy, Conquistador: Hernan Cortes, King Montezuma, and the Last Stands of the Aztecs, (New York: Bantam Books, 2008), 166.

- ↑ Levy, Buddy, Conquistador: Hernan Cortes, King Montezuma, and the Last Stands of the Aztecs, (New York: Bantam Books, 2008), 168–170.

- ↑ Levy, Buddy, Conquistador: Hernan Cortes, King Montezuma, and the Last Stands of the Aztecs, (New York: Bantam Books, 2008), 170–171.

- ↑ Levy, Buddy, Conquistador: Hernan Cortes, King Montezuma, and the Last Stands of the Aztecs, (New York: Bantam Books, 2008), 171.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10

- León-Portilla, Miguel (Ed.) (1992) [1959]. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Ángel María Garibay K. (Nahuatl-Spanish trans.), Lysander Kemp (Spanish-English trans.), Alberto Beltran (illus.) (Expanded and updated ed.). Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-5501-8.

- ↑ Smith 1996, 2003, p.275.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Gruzinski, Serge. The Aztecs: Rise and Fall of an Empire. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987.

- ↑ "Bernal Díaz del Castillo"

- ↑

- 1 2 3 León, Portilla Miguel. 2006 The Broken Spears: the Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Boston: Beacon

- ↑ (Leon-Portilla 1962: 117, León, Portilla Miguel. 2006 The Broken Spears: the Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Boston: Beacon

- ↑ (Diamond 1999: 210), Diamond, Jared M. 1999 Guns, Germs, and Steel: the Fates of Human Societies. New York: Norton.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 Diaz, B., 1963, The Conquest of New Spain, London: Penguin Books, ISBN 0140441239

- ↑ Robinson, Charles The Spanish Invasion of Mexico 1519-1521, London: Osprey, 2004 page 58.

- ↑ Robinson, Charles The Spanish Invasion of Mexico 1519-1521, London: Osprey, 2004 page 58.

- ↑ Robinson, Charles The Spanish Invasion of Mexico 1519-1521, London: Osprey, 2004 page 58.

- ↑ Robinson, Charles The Spanish Invasion of Mexico 1519-1521, London: Osprey, 2004 page 58.

- ↑ Robinson, Charles The Spanish Invasion of Mexico 1519-1521, London: Osprey, 2004 page 59.

- ↑ Robinson, Charles The Spanish Invasion of Mexico 1519-1521, London: Osprey, 2004 page 59.

- ↑ Robinson, Charles The Spanish Invasion of Mexico 1519-1521, London: Osprey, 2004 page 59.

- ↑ Robinson, Charles The Spanish Invasion of Mexico 1519-1521, London: Osprey, 2004 page 59.

- ↑ Robinson, Charles The Spanish Invasion of Mexico 1519-1521, London: Osprey, 2004 page 60.

- ↑ Robinson, Charles The Spanish Invasion of Mexico 1519-1521, London: Osprey, 2004 page 60.

- ↑ Robinson, Charles The Spanish Invasion of Mexico 1519-1521, London: Osprey, 2004 page 60.

- ↑ Robinson, Charles The Spanish Invasion of Mexico 1519-1521, London: Osprey, 2004 page 60.

References

Primary sources

- Cervantes de Salazar, Francisco. Crónica de la Nueva España. Madrid: Linkgua Ediciones, 2007. ISBN 84-9816-211-4

- Hernán Cortés, Letters – available as Letters from Mexico translated by Anthony Pagden (1986) ISBN 0-300-09094-3

- Francisco López de Gómara, Hispania Victrix; First and Second Parts of the General History of the Indies, with the whole discovery and notable things that have happened since they were acquired until the year 1551, with the conquest of Mexico and New Spain

- Bernal Díaz del Castillo, The Conquest of New Spain – available as The Discovery and Conquest of Mexico: 1517–1521 ISBN 0-306-81319-X

- León-Portilla, Miguel (Ed.) (1992) [1959]. The Broken Spears: The Aztec Account of the Conquest of Mexico. Ángel María Garibay K. (Nahuatl-Spanish trans.), Lysander Kemp (Spanish-English trans.), Alberto Beltran (illus.) (Expanded and updated ed.). Boston: Beacon Press. ISBN 0-8070-5501-8.

Secondary sources

- Andrea, Alfred J. and James H. Overfield. The Human Record: Sources of Global History, Volume II. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2005.

- Black, Jeremy, ed. World History Atlas. London: Dorling Kindersley, 2000.

- Gruzinski, Serge. The Aztecs: Rise and Fall of an Empire. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987.

- Hassig, Ross. Mexico and the Spanish Conquest. New York: Longman, 1994.

- Hassig, Ross. Mexico and the Spanish Conquest. 2nd edition. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 2006. ISBN 0-8061-3793-2 OCLC 64594483

- Conquest: Cortés, Montezuma, and the Fall of Old Mexico by Hugh Thomas (1993) ISBN 0-671-51104-1

- Cortés and the Downfall of the Aztec Empire by Jon Manchip White (1971) ISBN 0-7867-0271-0

- History of the Conquest of Mexico. by William H. Prescott ISBN 0-375-75803-8

- The Rain God cries over Mexico by László Passuth

- Seven Myths of the Spanish Conquest by Matthew Restall, Oxford University Press (2003) ISBN 0-19-516077-0

- The Conquest of America by Tzvetan Todorov (1996) ISBN 0-06-132095-1

- "Hernando Cortés" by Fisher, M. & Richardson K.

- "Hernando Cortés" Crossroads Resource Online.

- "Hernando Cortés" by Jacobs, W.J., New York, N.Y.:Franklin Watts, Inc. 1974.

- "The World’s Greatest Explorers: Hernando Cortés." Chicago, by Stein, R.C., Illinois: Chicago Press Inc. 1991.

- Davis, Paul K. (2003). "Besieged: 100 Great Sieges from Jericho to Sarajevo." Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- History of the Conquest of Mexico, with a Preliminary View of Ancient Mexican Civilization, and the Life of the Conqueror, Hernando Cortes By William H. Prescott

- The Aztecs by Michael E. Smith (1996, 2003), Blackwell Publishing, ISBN 0-631-23016-5

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire. |

- Hernando Cortes on the Web – web directory with thumbnail galleries

- Catholic Encyclopedia (1911)

- Conquistadors, with Michael Wood – website for 2001 PBS documentary

- Ibero-American Electronic Text Series presented online by the University of Wisconsin Digital Collections Center

- Página de relación

Coordinates: 19°26′06″N 99°07′53″W / 19.4350°N 99.1314°W