Siege of Rome (537–38)

| Siege of Rome | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Gothic War | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

| Eastern Roman Empire | Ostrogothic Kingdom | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

| Belisarius | Vitiges | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

5,000 men 5,600 reinforcements unknown number of conscripts | ~45,000 men | ||||||||

The First Siege of Rome during the Gothic War lasted for a year and nine days, from 2 March 537 to 12 March 538.[1] The city was besieged by the Ostrogothic army under their king Vitiges; the defending East Romans were commanded by Belisarius, one of the most famous and successful Byzantine generals. The siege was the first major encounter between the forces of the two opponents, and played a decisive role in the subsequent development of the war.

Background

With northern Africa back in Roman hands after the successful Vandalic War, Emperor Justinian I turned his sights on Italy, with the old capital, the city of Rome.

In the late 5th century, the peninsula had come under the control of the Ostrogoths, who, although they continued to acknowledge the Empire's suzerainty, had established a practically independent kingdom. However, after the death of its founder, the able Theodoric the Great, in 526, Italy descended into turmoil. Justinian took advantage of this to intervene in the affairs of the Ostrogoth state.

In 535, Mundus invaded Dalmatia, and Belisarius, with an army of 7,500 men, captured Sicily with ease.[2] From there, in June next year, he crossed over to Italy at Rhegium. After a twenty-day siege, the Romans sacked Naples in early November. After the fall of Naples, the Goths, who were enraged with the inactivity of their king, Theodahad, gathered in council and elected Vitiges as their new king.[3] Theodahad, who fled from Rome to Ravenna, was murdered by an agent of Vitiges on the way. In the meantime, Vitiges held a council at Rome, where it was decided not to seek immediate confrontation with Belisarius, but to wait until the main army, stationed in the north, was assembled. Vitiges then departed Rome for Ravenna, leaving a 4,000 strong garrison to secure the city.[4]

Nevertheless, the citizens of Rome decisively supported Belisarius, and, in the light of the brutal sack of Naples, were unwilling to support the risks of a siege. So, a delegation on behalf of Pope Silverius and eminent citizens was sent to Belisarius. The Ostrogoth garrison quickly realized that, with the population hostile, their position was untenable. Thus, on December 9, 536 AD, Belisarius entered Rome through the Asinarian Gate at the head of 5,000 troops, while the Ostrogoth garrison was leaving the city through the Flaminian Gate and headed north towards Ravenna.[5] After 60 years, Rome was once again in Roman hands.

The siege

Initial phases

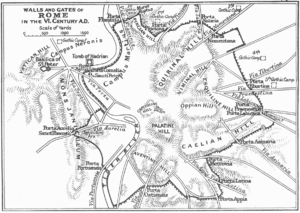

Belisarius, with his small force, was unable to continue his march northwards towards Ravenna, since the Ostrogoth forces vastly outnumbered his own. Instead, he settled in Rome, preparing for the inevitable counterstrike. He set up his headquarters on the Pincian Hill, in the north of the city, and started repairing the walls of the city. A ditch was dug out on the outer side, the fort of the Mausoleum of Hadrian strengthened, a chain was drawn across the Tiber, a number of citizens conscripted and stores of supplies set up. The populace of the city, aware that the siege they were trying to escape was becoming inevitable, started showing signs of discontent.

The Ostrogoth army marched on Rome, and gained passage over the river Anio at the Salarian Bridge, where the defending Romans abandoned their fortifications and fled. The next day, the Romans were barely saved from disaster when Belisarius, unaware of his forces' flight, proceeded towards the bridge with a detachment of his bucellarii. Finding the Goths already in possession of the fortified bridge, Belisarius and his escort became engaged in a fierce fight, and suffered great casualties before extricating themselves.[6]

Water mills

Rome was too large for the Goths to completely encircle. So they set up seven camps, overlooking the main gates and access routes to the city, in order to starve it out. Six of them were east of the river, and one on the western side, on the Campus Neronis, near the Vatican. This left the southern side of the city open.[7] The Goths then proceeded to block the aqueducts that were supplying the city with its water, necessary both for drinking and for operating the gristmills. The mills were those situated on the Janiculum, and provided most of the bread for the city. Although Belisarius was able to counter the latter problem by building floating mills on the stream of the Tiber, the hardships for the citizenry grew daily. Perceiving this discontent, Vitiges tried to achieve the surrender of the city, by promising the Roman army free passage, but the offer was refused.[8]

| “ | ...As for Rome, moreover, which we have captured, in holding it we hold nothing which belongs to others, but it was you who trespassed upon this city in former times, though it did not belong to you at all, and now you have given it back, however unwillingly, to its ancient possessors. And whoever of you has hopes of setting foot in Rome without a fight is mistaken in his judgment. For as long as Belisarius lives, it is impossible for him to relinquish this city. | ” |

First great assault

Soon after the rejection of his proposals, Vitiges unleashed a massive assault on the city. His engineers had constructed four great siege towers, which now began to be moved towards the city's northern walls, near the Salarian Gate, by teams of oxen. Procopius describes what happened next:

| “ | On the eighteenth day from the beginning of the siege the Goths moved against the fortifications at about sunrise [...] and all the Romans were struck with consternation at the sight of the advancing towers and rams, with which they were altogether unfamiliar. But Belisarius, seeing the ranks of the enemy as they advanced with the engines, began to laugh, and commanded the soldiers to remain quiet and under no circumstances to begin fighting until he himself should give the signal. | ” |

The reason for Belisarius' outburst was at first unclear, but as the Goths approached the moat, he drew forth his bow and shot, one after another, three Ostrogoth riders. The soldiers on the walls took this as an omen of victory and started to shout in celebration. Then Belisarius revealed his thought, as he ordered his archers to concentrate their fire on the exposed oxen, which the Goths had so thoughtlessly brought within bowshot distance from the walls. The oxen were dispatched quickly, and the four towers were left there, useless, before the walls.[9]

Vitiges then left a large force to keep the defenders occupied, and attacked the walls to the southeast, in the area of the Praenestine Gate, known as the Vivarium, where the fortifications were lower. A simultaneous attack was carried out in the western side, at the Mausoleum of Hadrian and the Cornelian Gate. There the fighting was particularly fierce. Eventually, after a hard fight, the Goths were driven off,[10] but the situation at the Vivarium was grave. The defenders, under Bessas and Peranius, were being hard pressed, and sent to Belisarius for help. Belisarius came, accompanied by a few of his bucellarii. As soon as the Goths breached the wall, he ordered a few soldiers to attack them before they could form up, but with the majority of his troops, he sallied forth from the gate. Taking the Goths by surprise, his men pushed them back and burned their siege engines. At the same time, whether by chance or design, the Romans at the Salarian Gate also attempted a sortie, and likewise succeeded in destroying many of the siege engines. The first attempt of the Goths to storm the city had failed, and their army withdrew to their camps.[11]

Roman successes

Despite this success, Belisarius was well aware that his situation was still dangerous. He therefore wrote a letter to Justinian, asking for aid. Indeed, Justinian had already dispatched reinforcements under the tribunes Martinus and Valerian, but they had been delayed in Greece due to bad weather. In his letter, Belisarius also added cautionary words concerning the loyalty of the populace: "And although at the present time the Romans are well disposed toward us, yet when their troubles are prolonged, they will probably not hesitate to choose the course which is better for their own interests. [...] Furthermore, the Romans will be compelled by hunger to do many things they would prefer not to do."[12] For fear of treason, extreme measures were taken by Belisarius: Pope Silverius was deposed on suspicions of negotiating with the Goths and replaced by Vigilius, the locks and keys of the gates were changed "twice each month", the guards on gate duty regularly rotated, and patrols set up.[13]

Vitiges, in the meantime, enraged by his failure, sent orders to Ravenna to kill the senators that he had held hostage there, and furthermore resolved to complete the isolation of the besieged city by cutting it off from the sea. The Goths seized the Portus Claudii at Ostia, which had been left unguarded by the Romans. As a result, although the Romans retained control of Ostia itself, their supply situation worsened, as supplies had to be unloaded at Antium (modern Anzio) and thence transported laboriously to Rome.[14] Fortunately for the besieged, twenty days later, the promised reinforcements, 1600 cavalry, arrived and were able to enter the city. Belisarius now had at his disposal a well-trained, disciplined and mobile force, and started employing his cavalry in sallies against the Goths. Invariably, the Roman horsemen, mostly of Hunnic or Slavic origin and expert bowmen, would close in on the Goths, who relied primarily on close quarters combat and lacked ranged weapons, loose a shower of arrows, and withdraw to the walls when pursued. There, ballistas and catapults lay in waiting, and drove the Goths back with great loss. Thus the superior mobility and firepower of the Roman cavalry was utilized to great effect, causing serious losses to the Goths for minimal Roman casualties.[15]

The Goths achieve victory in open battle

These successes greatly encouraged the army and the people, who now put pressure on Belisarius to march forth into an open battle. At first Belisarius refused because of the still-great numerical disparity, but was at length persuaded, and made his preparations accordingly. The main force, under his command, would sally forth from the Pincian and the Salarian Gates in the north, while a smaller cavalry detachment under Valentinus, along with the bulk of the armed civilians, would confront the large Gothic force encamped west of the Tiber and prevent them from participating in the battle, without however engaging it in direct combat. Initially, and since in those times Roman infantry was a far cry from the legions of earlier times, Belisarius wished the battle to be restricted to a cavalry fight, but was persuaded by the pleas of two of his bodyguards, Principius and Tarmutus, and positioned a large body of his infantry under them as a reserve and rally point for the cavalry.[16]

Vitiges, for his part, deployed his army in the typical fashion, with the infantry in the center and the cavalry on the flanks. When battle was joined, the Roman cavalry once again utilized its familiar tactics, showering the dense mass of Gothic troops with arrows and withdrawing without contact. Thus they inflicted great casualties on the Goths, who were unable to adapt to these tactics, and by midday, the Romans seemed close to victory. On the Fields of Nero, on the other side of the Tiber, the Romans attempted a sudden attack on the Goths, and, due to shock and large numbers, the Goths were routed and fled to the hills for safety. But the majority of the Roman army there, as mentioned, consisted of ill-disciplined civilians, who soon lost any semblance of order, despite Valentinus' and his officers' efforts, and went about plundering the abandoned Gothic camp. This confusion gave the Goths the time to regroup, and charging once again, they drove the Romans back with great loss. In the meantime, on the eastern side of the Tiber, the Romans had reached the Gothic camps. There resistance was fierce, and the already small Roman force suffered casualties in close combat. Thus, when the Gothic cavalry in the right wing perceived their opponents' weakness, they moved against them and routed them. Soon the Romans were in full flight, and the infantry, which was supposed to act in exactly such a case as a defensive screen, disintegrated despite the valor of Principius and Tarmutus and joined the flight for the safety of the walls.[17]

Roman ascendancy and end of the siege

| And the barbarians said: "[...] we give up to you Sicily, great as it is and of such wealth, seeing that without it you cannot possess Libya in security."7

And Belisarius replied: "And we on our side permit the Goths to have the whole of Britain, which is much larger than Sicily and was subject to the Romans in early times. For it is only fair to make an equal return to those who first do a good deed or perform a kindness." The barbarians: "Well, then, if we should make you a proposal concerning Campania also, or about Naples itself, will you listen to it?" Belisarius: "No, for we are not empowered to administer the emperor's affairs in a way which is not in accord with his wish." |

| Dialogue between Belisarius and the Gothic embassy Procopius, De Bello Gothico II.VI |

The Goths, also suffering, like the besieged, from disease and famine, now resorted to diplomacy. An embassy of three was sent to Belisarius, and offered to surrender Sicily and southern Italy (which were already in Roman hands) in exchange for a Roman withdrawal. The dialogue, as preserved by Procopius, clearly illustrates the reversed situation of the two parties, with the envoys claiming having suffered injustice and offering territories, and Belisarius being secure in his position, dismissive of the Goths' claims, and even making sarcastic remarks at their proposals. Nevertheless, a three-month armistice was arranged in order for Gothic envoys to travel to Constantinople for negotiations.[18] Belisarius took advantage of it and brought the 3,000 Isaurians, who had landed at Ostia, along with a large amount of supplies, safely to Rome. During the armistice, the Goths' situation deteriorated for want of supplies, and they were forced to abandon the Portus, which was promptly occupied by an Isaurian garrison, as well as the city of Centumcellae (modern Civitavecchia) and Albano. Thus, by the end of December, the Goths were virtually surrounded by Roman detachments, and their supply routes effectively cut. The Goths protested these actions, but to no avail. Belisarius even sent one of his best generals, John, with 2,000 men towards Picenum, with orders to avoid conflict but, when ordered to move, to capture or plunder any stronghold he met, and not to leave any enemy strongholds in his rear.[19]

Shortly thereafter the truce was irretrievably broken by the Goths, when they attempted to enter the city in secret. First they tried to do so by using the Aqua Virgo aqueduct. Unfortunately for them, the torches they used to explore it were detected by a guard on the nearby Pincian Gate. The aqueduct was put under close guard, and the Goths, perceiving this, made no attempt to use it again. A little later, a sudden attack against the same gate was repulsed by the guards under the command of Ildiger, Antonina's son-in-law. Later, with the aid of two paid Roman agents, they tried to drug the guards at a section of the walls near St Peter's and enter the city unopposed, but one of the agents revealed the plan to Belisarius, and this attempt too was thwarted.[20]

In retaliation, Belisarius ordered John to move on Picenum. John, after defeating a Gothic force under Ulithus, an uncle of Vitiges, was free to roam the province at will. However, he disobeyed Belisarius' instructions, and did not attempt to take the fortified towns of Auxinum (modern Osimo) and Urbinum (modern Urbino), judging that they were too strong. Instead, he bypassed them and headed for Ariminum (Rimini), invited there by the local Roman population. Ariminum's capture meant that the Romans had effectively cut Italy in two, but in addition, the city was barely a day's march away from the Gothic capital of Ravenna. Thus, at the news of Ariminum's fall, Vitiges decided to withdraw in all haste towards his capital. 374 days after the siege had begun, the Goths burned their camps and abandoned Rome, marching northeast along the Via Flaminia. But Belisarius led out his forces, and waited until half the Gothic army had crossed the Milvian Bridge before attacking the remainder. After initially fierce resistance, the Goths finally broke, and many were slain or drowned in the river.[21]

Aftermath

After their victory over a numerically much superior enemy, the Romans gained the upper hand. Reinforcements under Narses arrived, which enabled Belisarius to take several Gothic strongholds and control most of Italy south of the River Po by the end of 539. Eventually, Ravenna itself was taken by deceit in May 540, and the war seemed to be effectively over. However, very soon, the Goths, under the capable leadership of their new king Totila, managed to reverse the situation, until the Empire's position in Italy almost collapsed. In 546, Rome was again besieged by Totila, and this time Belisarius was unable to prevent its fall. The city was reoccupied by the Imperials soon after, and Totila had to besiege it again in 549. Despite the city's fall, Totila's triumph was to be brief. The arrival of Narses in 551 spelled the beginning of the end for the Goths, and in the Battle of Taginae in 552 the Goths were routed and Totila was killed. In 553 the last Ostrogothic king, Teia, was defeated. Although several cities in the north continued resistance up to the early 560s, Gothic power was broken for good.

References

- ↑ Dupuy & Dupuy, p. 203 (cf. Lillington-Martin, 2013: 610-21)

- ↑ Bury (1923), Ch. XVIII, p. 170-171

- ↑ Bury (1923), Ch. XVIII, p. 175-177

- ↑ Bury (1923), Ch. XVIII, p. 178

- ↑ Bury (1923), Ch. XVIII, p. 180

- ↑ Bury (1923), Ch. XIX, p. 182-183 and Lillington-Martin (2013), p. 611-22.

- ↑ Bury (1923), Ch. XIX, p. 183

- ↑ Bury (1923), Ch. XIX, p. 185

- ↑ Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.XXII

- ↑ Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.XXII

- ↑ Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.XXIII

- ↑ Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.XXIV

- ↑ Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.XXV

- ↑ Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.XXVI

- ↑ Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.XXVII

- ↑ Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.XXVIII

- ↑ Procopius, De Bello Gothico I.XXIX

- ↑ Procopius, De Bello Gothico II.VI

- ↑ Procopius, De Bello Gothico II.VII

- ↑ Procopius, De Bello Gothico II.IX

- ↑ Procopius, De Bello Gothico II (cf. Lillington-Martin, 2013: 625-26).

Sources

- Procopius, De Bello Gothico, Volumes I. & II.

- Bury, John Bagnell (1923). History of the Later Roman Empire Vols. I & II. Macmillan & Co., Ltd.

- Richard Ernest Dupuy; Trevor Nevitt Dupuy (April 1993). The Harper encyclopedia of military history: from 3500 BC to the present. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-270056-8. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- Hughes, Ian (2009). Belisarius:The Last Roman General. Yardley, PA: Westholme Publishing, LLC. ISBN 978-1-59416-528-3.

- Lillington-Martin, Christopher

2013b “Procopius on the struggle for Dara and Rome” in: War and Warfare in Late Antiquity: Current Perspectives (Late Antique Archaeology 8.1-8.2 2010-11) by SarantisA. and Christie N. (2010–11) edd. (Brill, Leiden 2013), pages 599-630

2013a, "La defensa de Roma por Belisario" in: Justiniano I el Grande (Desperta Ferro) edited by Alberto Pérez Rubio, 18 (July 2013), pages 40–45, ISSN 2171-9276;

Coordinates: 41°54′00″N 12°30′00″E / 41.9000°N 12.5000°E