Shunt (electrical)

In electronics, a shunt is a device which allows electric current to pass around another point in the circuit by creating a low resistance path. The term is also widely used in photovoltaics to describe an unwanted short circuit between the front and back surface contacts of a solar cell, usually caused by wafer damage. The origin of the term is in the verb 'to shunt' meaning to turn away or follow a different path.

| Look up shunt in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Defective device bypass

One example is in miniature Christmas lights which are wired in series. When the filament burns out in one of the incandescent light bulbs, the electrical resistance becomes very high. The much higher voltage that this creates (equal to the full line voltage rather than the normal voltage divider level) causes the shunt to short out (becoming an antifuse) and become part of the circuit, again allowing electricity to pass and the set to light. If too many lights burn out however, a shunt will also burn out, requiring the use of a multimeter to find the point of failure.

Lightning arrestor

A gas-filled tube can also be used as a shunt, particularly in a lightning arrestor. Neon and other noble gases have a high breakdown voltage, so that normally current will not flow across it. However, a direct lightning strike (such as on a radio tower antenna) will cause the shunt to arc and conduct the massive amount of electricity to ground, protecting transmitters and other equipment.

Another older form of lightning arrestor employs a simple narrow spark gap, over which an arc will jump when a high voltage is present. While this is a low cost solution, its high triggering voltage offers almost no protection for modern solid-state electronic devices powered by the protected circuit.

Electrical noise bypass

Capacitors are used as shunts to redirect high-frequency noise to ground before it can propagate to the load or other circuit components.

Use in electronic filter circuits

The term shunt is used in filter and similar circuits with a ladder topology to refer to the components connected between the line and common. The term is used in this context to distinguish the shunt connected components from the series connected components in parallel with the line. More generally, the term shunt can be used for a component connected in parallel with another. For instance, shunt m-derived half section is a common filter section from the image impedance method of filter design.[1]

Diodes as shunts

Where devices are especially sensitive to reverse polarity of signal or power supply, a diode may be used to protect the circuit. If connected in series with the circuit it simply prevents reversed current, but if connected in parallel it can shunt the reversed supply, causing a fuse or other current limiting circuit to open.

Shunts as circuit protection

When a circuit must be protected from overvoltage and there are failure modes in the power supply that can produce such overvoltages, the circuit may be protected by a device commonly called a crowbar circuit. When this device detects an overvoltage it causes a short circuit between the power supply and its return. This will cause both an immediate drop in voltage (protecting the device) and an instantaneous high current which is expected to open a current sensitive device (such as a fuse or circuit breaker). This device is called a crowbar as it is likened to dropping an actual crowbar across a set of bus bars (exposed electrical conductors).

Use in current measuring

An ammeter shunt allows the measurement of current values too large to be directly measured by a particular ammeter. In this case the shunt, a manganin resistor of accurately known resistance, is placed in series with the load, thus all of the current to be measured will flow through it. In order not to disrupt the circuit, the resistance of the shunt is normally very small. The voltage drop across the shunt is proportional to the current flowing through it and since its resistance is known, a voltmeter connected across the shunt can be scaled to directly display the current value.

Shunts are rated by maximum current and voltage drop at that current. For example, a 500 A, 75 mV shunt would have a resistance of 0.15 milliohms, a maximum allowable current of 500 amps and at that current the voltage drop would be 75 millivolts. By convention, most shunts are designed to drop 50 mV, 75 mV or 100 mV when operating at their full rated current and most ammeters consist of a shunt and a voltmeter with full-scale deflections of 50, 75, or 100 mV. All shunts have a derating factor for continuous use, 66% being the most common. Continuous use is a run time of 2+ minutes, at which point the derating factor must be applied. There are thermal limits where a shunt will no longer operate correctly. At 80 °C thermal drift begins to occur, at 120 °C thermal drift is a significant problem where error, depending on the design of the shunt, can be several percent and at 140 °C the manganin alloy becomes permanently damaged due to annealing resulting in the resistance value drifting up or down.

If the current being measured is also at a high voltage potential this voltage will be present in the connecting leads to and in the reading instrument itself. Sometimes, the shunt is inserted in the return leg (grounded side) to avoid this problem. Some alternatives to shunts can provide isolation from the high voltage by not directly connecting the meter to the high voltage circuit. Examples of devices that can provide this isolation are Hall effect current sensors and current transformers (see clamp meters). Current shunts are considered more accurate and cheaper than Hall effect devices. Common accuracy of such devices are ±0.1% & 0.25% and 0.5%.

The Thomas-type double manganin walled shunt and MI type (improved Thomas-type design) were used until the 1990s by NIST and other government labs as the legal reference of an ohm until the advent of the quantum Hall effect. Thomas-type shunts are still used by government and private labs to take very accurate current measurements, as using quantum Hall effect is a time consuming process. The accuracy of these types of shunts is measured in the ppm and sub-ppm scale of drift per year of set resistance.

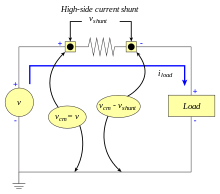

Current measurement techniques

Where the circuit is grounded (earthed) on one side, a current measuring shunt can be inserted either in the ungrounded conductor or in the grounded conductor. A shunt in the ungrounded conductor must be insulated for the full circuit voltage to ground; the measuring instrument must be inherently isolated from ground or must include a resistive voltage divider or an isolation amplifier between the relatively high common-mode voltage and lower voltages inside the instrument. A shunt in the grounded conductor may not detect leakage current that bypasses the shunt, but it will not experience high common-mode voltage to ground. The load is removed from a direct path to ground, which may create problems for control circuitry, result in unwanted emissions, or both.

See also

References

- ↑ Matthaei, Young, Jones Microwave Filters, Impedance-Matching Networks, and Coupling Structures, p66, McGraw-Hill 1964