Shark Bay

| Shark Bay, Western Australia | |

|---|---|

| Name as inscribed on the World Heritage List | |

|

Shark Bay | |

| Location | Gascoyne region, Western Australia, Australia |

| Type | Natural |

| Criteria | vii, viii, ix, x |

| Reference | 578 |

| UNESCO region | Asia-Pacific |

| Coordinates | 25°30′S 113°30′E / 25.500°S 113.500°ECoordinates: 25°30′S 113°30′E / 25.500°S 113.500°E |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1991 (15th Session) |

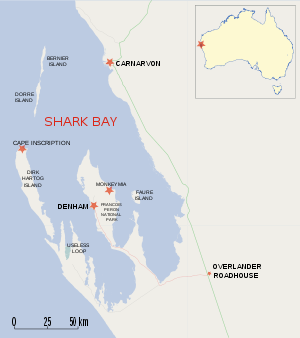

Location of Shark Bay at the most westerly point of the Australian continent | |

Shark Bay is a World Heritage Site in the Gascoyne region of Western Australia. The 2,200,902-hectare (5,438,550-acre) heritage–listed area is located approximately 800 kilometres (500 mi) north of Perth, on the westernmost point of the Australian continent, inscribed as follows:[1]

...Shark Bay’s waters, islands and peninsulas....have a number of exceptional natural features, including one of the largest and most diverse seagrass beds in the world. However it is for its stromatolites (colonies of microbial mats that form hard, dome-shaped deposits which are said to be the oldest life forms on earth), that the property is most renowned. The property is also famous for its rich marine life including a large population of dugongs, and provides a refuge for a number of other globally threatened species.

The record of Australian Aboriginal occupation of Shark Bay extends to 22,000 years BP. At that time most of the area was dry land, rising sea levels flooding Shark Bay between 8,000 BP and 6,000 BP. A considerable number of aboriginal midden sites have been found, especially on Peron Peninsula and Dirk Hartog Island which provide evidence of some of the foods gathered from the waters and nearby land areas.[1] An expedition led by Dirk Hartog happened upon the area in 1616, becoming the second group of Europeans known to have visited Australia, after the crew of the Duyfken, under Willem Janszoon, visited Cape York in 1606. Shark Bay was named by William Dampier, on 7 August 1699.[2]

The heritage–listed area had a population of fewer than 1,000 people as at the 2011 census and a coastline of over 1,500 kilometres (930 mi). The half-dozen small communities making up this population occupy less than 1% of the total area.

Shark Bay World Heritage site

The World Heritage status of the region was created and negotiated in 1991.[3] The site was gazetted on the Australian National Heritage List on 21 May 2007[4] under the Environment and Heritage Legislation Amendment Act (No. 1), 2003 (Cth).[5]

Protected areas

Inscribed as a World Heritage Site in 1991, the site covers an area of 2,200,902 hectares (5,438,550 acres), of which about 70 per cent are marine waters. It includes many protected areas and conservation reserves, including Shark Bay Marine Park, Francois Peron National Park, Hamelin Pool Marine Nature Reserve, Zuytdorp Nature Reserve and numerous protected islands.[1] Denham and Useless Loop both fall within the boundary of the site, yet are specifically excluded from it. Shark Bay was the first Australian site to be classified on the World Heritage list.

Landforms

The bay itself covers an area of 1,300,000 hectares (3,200,000 acres), with an average depth of 9 metres (30 ft).[1] It is divided by shallow banks and has many peninsulas and islands. The coastline is over 1,500 kilometres (930 mi) long. There are about 300 kilometres (190 mi) of limestone cliffs overlooking the bay.[6] One spectacular segment of cliffs is known as the Zuytdorp Cliffs. The bay is located in the transition zone between three major climatic regions and between two major botanical provinces.

Dirk Hartog Island is of historical significance due to landings upon it by early explorers. In 1616, Dirk Hartog landed at Inscription Point on the north end of the island and marked his discovery with a pewter plate, inscribed with the date and nailed to a post. This plate was then replaced by Willem de Vlamingh and returned to Holland. It is now kept in the National Museum of Holland. There is a replica in the Shark Bay Discovery Centre in Denham.

Bernier and Dorre islands in the north-west corner of the heritage area are among the last-remaining habitats of Australian mammals threatened with extinction. They are used, with numerous other smaller islands throughout the marine park, to release threatened species that are being bred at Project Eden in François Peron National Park. These islands are free of feral non-native animals which might predate the threatened species, and so provide a safe haven of pristine environment on which to restore species that are threatened on the mainland.

The Australian Wildlife Conservatory is the guardian of Faure Island, off Monkey Mia. Seasonally, sea turtles come here to nest and are the subject of studies conducted in conjunction with the Western Australian Department of Environment and Conservation (DEC) on this sheltered island.

Fauna

Shark Bay is an area of major zoological importance. It is home to about 10,000 dugongs (‘sea cows’), around 12.5% of the world's population,[6] and there are many Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins, particularly at Monkey Mia. The dolphins here have been particularly friendly since the 1960s.[6] The area supports 26 threatened Australian mammal species, over 230 species of bird, and nearly 150 species of reptile. It is an important breeding and nursery ground for fish, crustaceans, and coelenterates. There are over 323 fish species, with many of them sharks and rays.

Some bottlenose dolphins in Shark Bay exhibit one of the few known cases of tool use in marine mammals (along with sea otters): they protect their nose with a sponge while foraging for food in the sandy sea bottom. humpback and southern right whales use the waters of the bay as migratory staging post[6] while other species such as Bryde's whale come into the bay less frequently but to feed or rest. The threatened green and loggerhead sea turtles nest on the bay's sandy beaches. The largest fish in the world, the whale shark, gathers in the bay during the April and May full moons.[6]

Flora

Shark Bay has the largest known area of seagrass, with seagrass meadows covering over 480,000 hectares (1,200,000 acres) of the bay.[6] It includes the 103,000-hectare (250,000-acre) Wooramel Seagrass Bank, the largest seagrass bank in the world.[4] Shark Bay also contains the largest number of seagrass species ever recorded in one place; twelve species have been found, with up to nine occurring together in some places. The seagrasses are a vital part of the complex environment of the bay. Over thousands of years, sediment and shell fragments have accumulated in the seagrasses to form vast expanses of seagrass beds. This has raised the sea floor, making the bay shallower. Seagrasses are the basis of the food chain in Shark Bay, providing home and shelter to various marine species and attracting the dugong population.

In Shark Bay's hot, dry climate, evaporation greatly exceeds the annual precipitation rate. Thus, the seawater in the shallow bays becomes very salt-concentrated, or 'hypersaline'. Seagrasses also restrict the tidal flow of waters through the bay area, preventing the ocean tides from diluting the sea water. The water of the bay is 1.5 to 2 times more salty than the surrounding ocean waters.

Stromatolites

About 1,000 years ago cyanobacteria (blue-green algae) began building up stromatolites in Hamelin Pool at the Hamelin Station reserve in the southern part of the bay.[7][8] These structures are modern equivalents of the earliest signs of life on Earth, with fossilized stromatolites being found dating from 3.5 billion years ago at North Pole near Marble Bar, in Western Australia, and are considered the longest continuing biological lineage.[6] They were first identified in 1956 at Hamelin Pool as a living species, before that only being known in the fossil record. Hamelin Pool contains the most diverse and abundant examples of living stromatolite forms in the world. Other occurrences are found at Lake Clifton near Mandurah and Lake Thetis near Cervantes.[4] It is hypothesized that some stromatolites contain a new form of chlorophyll, chlorophyll f.[9]

Shark Bay World Heritage Discovery Centre

Facilities around the World Heritage area, provided by the Shire of Shark Bay and the WA Department of Environment and Conservation, include the Shark Bay World Heritage Discovery Centre in Denham which provides interactive displays and comprehensive information about the features of the region.

Access

Access to Shark Bay is by air via Shark Bay Airport, and by the World Heritage Drive, a 150 km link road between Denham and the Overlander Roadhouse on the North West Coastal Highway.

Specific reserved areas

National parks and reserves in the World Heritage Area

- Bernier Island

- Dorre Island

- Charlie Island

- Francois Peron National Park

- Friday Island

- Hamelin Pool Marine Nature Reserve

- Hamelin Pool/East Faure Island High-Low Water Mark

- Koks Island

- Monkey Mia

- Shark Bay Marine Park

- Shell Beach

- Small Islands

- Zuytdorp Nature Reserve

Bays of the World Heritage area

Islands of the World Heritage area

Peninsulas of the World Heritage area

- Bellefin Prong

- Heirisson Prong

- Carrarang Peninsula

- Peron Peninsula

IBRA sub regions of the Shark Bay Area

The Shark Bay area has three bioregions within the Interim Biogeographic Regionalisation for Australia (IBRA) system: Carnarvon, Geraldton Sandplains, and Yalgoo. The bioregions are further divided into sub–bioregions:[10]

- Carnarvon bioregion (CAR) –

- Wooramel sub region (CAR2) – most of Peron Peninsula and coastline east of Hamelin Pool

- Cape Range sub region (CAR1) – (not represented in area)

- Geraldton Sandplains bioregion (GS) –

- Geraldton Hills sub region (GS1) – Zuytdorp Nature Reserve area

- Leseur sub region (GS2) – (not represented in area)

- Yalgoo bioregion (YAL) –

- Tallering sub region (YAL2) (not represented in area)

- Edel subregion (YAL1) – Bernier, Dorre and Dirk Hartog Islands

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Shark Bay, Western Australia". World Heritage List. UNESCO. 2014. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- ↑ Burney, James (1803). "7. Voyage of Captain William Dampier, in the Roebuck, to New Holland". A Chronological History of the Discoveries in the South Sea or Pacific Ocean. 4. London: G. & W. Nicol, G. & J. Robinson & T. Payne. p. 395. Retrieved 9 October 2013.

- ↑ Agreement between the state of Western Australia and the Commonwealth of Australia on administrative arrangements for the Shark Bay World Heritage Property in Western Australia. WA Department of Conservation and Land Management. Perth, W.A.: Government of Western Australia. 12 September 1997.

- 1 2 3 "Shark Bay, Western Australia". Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities. Australian Government. 3 September 2008. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ↑ "Determination regarding including World Heritage places in the National Heritage List" (PDF). Special government gazette (PDF). Department of the Environment and Water Resources, Commonwealth of Australia. 21 May 2007. Retrieved 30 August 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Riley, Laura and William (2005). Nature's Strongholds: The World's Great Wildlife Reserves. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press. pp. 595–596. ISBN 0-691-12219-9. Retrieved 12 July 2011.

- ↑ Giusfredi, Paige E. (22 July 2014). Hamelin Pool Stromatolites: Ages and Interactions with the Depositional Environment. Miami, FL: University of Miami. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

- ↑ "Stromatolites of Shark Bay: Nature fact sheets". WA Department of Environment and Conservation. Government of Western Australia. Retrieved 3 September 2011.

- ↑ Avolio C. (20 August 2010). "First new chlorophyll in 60 years discovered" (Press release). Faculty of Science, The University of Sydney.

- ↑ "Bioregions; Figure 4: IBRA sub-regions of the Shark Bay Area (map)". Shark Bay terrestrial reserves and proposed reserve additions: draft management plan 2007. WA Department of Environment and Conservation; Conservation Commission of Western Australia. Bentley, WA: Government of Western Australia. 2007. pp. 37–39.

Further reading

- Duyker, Edward (2006). François Péron: An Impetuous Life: Naturalist and Voyager. Melbourne, Victoria: Miegunyah/MUP. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-522-85260-8. (Winner, Frank Broeze Maritime History Prize, 2007).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Shark Bay. |

- Official websites

- UNESCO World Heritage List: Shark Bay, Western Australia

- Australian National Heritage Register listing for Shark Bay, Western Australia

- "Shark Bay, Western Australia" (PDF) (Map). Department of the Environment and Water Resources. Australian Government. 22 May 2007.

- Shark Bay World Heritage Discovery Centre

- Shark Bay World Heritage Area

- Additional information