Manorialism

Manorialism, an essential element of feudal society,[1] was the organizing principle of rural economy that originated in the villa system of the Late Roman Empire,[2] was widely practiced in medieval western and parts of central Europe, and was slowly replaced by the advent of a money-based market economy and new forms of agrarian contract.

Manorialism was characterised by the vesting of legal and economic power in a Lord of the Manor, supported economically from his own direct landholding in a manor (sometimes called a fief), and from the obligatory contributions of a legally subject part of the peasant population under the jurisdiction of himself and his manorial court. These obligations could be payable in several ways, in labor (the French term corvée is conventionally applied), in kind, or, on rare occasions, in coin.

In examining the origins of the monastic cloister, Walter Horn found that "as a manorial entity the Carolingian monastery ... differed little from the fabric of a feudal estate, save that the corporate community of men for whose sustenance this organization was maintained consisted of monks who served God in chant and spent much of their time in reading and writing."[3]

Manorialism died slowly and piecemeal, along with its most vivid feature in the landscape, the open field system. It outlasted serfdom as it outlasted feudalism: "primarily an economic organization, it could maintain a warrior, but it could equally well maintain a capitalist landlord. It could be self-sufficient, yield produce for the market, or it could yield a money rent."[4] The last feudal dues in France were abolished at the French Revolution. In parts of eastern Germany, the Rittergut manors of Junkers remained until World War II.[5] In Quebec, the last feudal rents were paid in 1970 under the modified provisions of the Seigniorial Dues Abolition Act of 1935.

Historical and geographical distribution

.jpg)

The term is most often used with reference to medieval Western Europe. Antecedents of the system can be traced to the rural economy of the later Roman Empire (Dominate). With a declining birthrate and population, labor was the key factor of production. Successive administrations tried to stabilise the imperial economy by freezing the social structure into place: sons were to succeed their fathers in their trade, councilors were forbidden to resign, and coloni, the cultivators of land, were not to move from the land they were attached to. The workers of the land were on their way to becoming serfs.[6]

Several factors conspired to merge the status of former slaves and former free farmers into a dependent class of such coloni: it was possible to be described as servus et colonus, "both slave and colonus".[7] Laws of Constantine I around 325 both reinforced the semi-servile status of the coloni and limited their rights to sue in the courts; the Codex Theodosianus promulgated under Theodosius II extended these restrictions. The legal status of adscripti, "bound to the soil",[8] contrasted with barbarian foederati, who were permitted to settle within the imperial boundaries, remaining subject to their own traditional law.

As the Germanic kingdoms succeeded Roman authority in the West in the fifth century, Roman landlords were often simply replaced by Gothic or Germanic ones, with little change to the underlying situation or displacement of populations.

The process of rural self-sufficiency was given an abrupt boost in the eighth century, when normal trade in the Mediterranean Sea was disrupted. The thesis put forward by Henri Pirenne, while disputed widely, supposes that the Arab conquests forced the medieval economy into even greater ruralization and gave rise to the classic feudal pattern of varying degrees of servile peasantry underpinning a hierarchy of localised power centers.

History

The word derives from traditional inherited divisions of the countryside, reassigned as local jurisdictions known as manors or seigneuries; each manor being subject to a lord (French seigneur), usually holding his position in return for undertakings offered to a higher lord (see Feudalism). The lord held a manorial court, governed by public law and local custom. Not all territorial seigneurs were secular; bishops and abbots also held lands that entailed similar obligations.

By extension, the word manor is sometimes used in England to mean any home area or territory in which authority is held, often in a police or criminal context.[9][10]

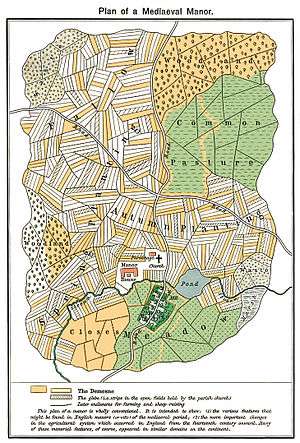

In the generic plan of a medieval manor from Shepherd's Historical Atlas, the strips of individually worked land in the open field system are immediately apparent. In this plan, the manor house is set slightly apart from the village, but equally often the village grew up around the forecourt of the manor, formerly walled, while the manor lands stretched away outside, as still may be seen at Petworth House. As concerns for privacy increased in the 18th century, manor houses were often located a farther distance from the village. For example, when a grand new house was required by the new owner of Harlaxton Manor, Lincolnshire, in the 1830s, the site of the existing manor house at the edge of its village was abandoned for a new one, isolated in its park, with the village out of view.

In an agrarian society, the conditions of land tenure underlie all social or economic factors. There were two legal systems of pre-manorial landholding. One, the most common, was the system of holding land "allodially" in full outright ownership. The other was a use of precaria or benefices, in which land was held conditionally (the root of the English word "precarious").

To these two systems, the Carolingian monarchs added a third, the aprisio, which linked manorialism with feudalism. The aprisio made its first appearance in Charlemagne's province of Septimania in the south of France, when Charlemagne had to settle the Visigothic refugees, who had fled with his retreating forces, after the failure of his Zaragoza expedition of 778. He solved this problem by allotting "desert" tracts of uncultivated land belonging to the royal fisc under direct control of the emperor. These holdings aprisio entailed specific conditions. The earliest specific aprisio grant that has been identified was at Fontjoncouse, near Narbonne (see Lewis, links). In former Roman settlements, a system of villas, dating from Late Antiquity, was inherited by the medieval world.

Common features

Manors each consisted of up to three classes of land:

- Demesne, the part directly controlled by the lord and used for the benefit of his household and dependents;

- Dependent (serf or villein) holdings carrying the obligation that the peasant household supply the lord with specified labour services or a part of its output (or cash in lieu thereof), subject to the custom attached to the holding; and

- Free peasant land, without such obligation but otherwise subject to manorial jurisdiction and custom, and owing money rent fixed at the time of the lease.

Additional sources of income for the lord included charges for use of his mill, bakery or wine-press, or for the right to hunt or to let pigs feed in his woodland, as well as court revenues and single payments on each change of tenant. On the other side of the account, manorial administration involved significant expenses, perhaps a reason why smaller manors tended to rely less on villein tenure.

Dependent holdings were held nominally by arrangement of lord and tenant, but tenure became in practice almost universally hereditary, with a payment made to the lord on each succession of another member of the family. Villein land could not be abandoned, at least until demographic and economic circumstances made flight a viable proposition; nor could they be passed to a third party without the lord's permission, and the customary payment.

Although not free, villeins were by no means in the same position as slaves: they enjoyed legal rights, subject to local custom, and had recourse to the law subject to court charges, which were an additional source of manorial income. Sub-letting of villein holdings was common, and labour on the demesne might be commuted into an additional money payment, as happened increasingly from the 13th century.

This description of a manor house at Chingford, Essex in England was recorded in a document for the Chapter of St Paul's Cathedral when it was granted to Robert Le Moyne in 1265:

- He received also a sufficient and handsome hall well ceiled with oak. On the western side is a worthy bed, on the ground, a stone chimney, a wardrobe and a certain other small chamber; at the eastern end is a pantry and a buttery. Between the hall and the chapel is a sideroom. There is a decent chapel covered with tiles, a portable altar, and a small cross. In the hall are four tables on trestles. There are likewise a good kitchen covered with tiles, with a furnace and ovens, one large, the other small, for cakes, two tables, and alongside the kitchen a small house for baking. Also a new granary covered with oak shingles, and a building in which the dairy is contained, though it is divided. Likewise a chamber suited for clergymen and a necessary chamber. Also a hen-house. These are within the inner gate. Likewise outside of that gate are an old house for the servants, a good table, long and divided, and to the east of the principal building, beyond the smaller stable, a solar for the use of the servants. Also a building in which is contained a bed, also two barns, one for wheat and one for oats. These buildings are enclosed with a moat, a wall, and a hedge. Also beyond the middle gate is a good barn, and a stable of cows, and another for oxen, these old and ruinous. Also beyond the outer gate is a pigstye.[11]

Variation among manors

Like feudalism which, together with manorialism, formed the legal and organizational framework of feudal society, manorial structures were not uniform. In the later Middle Ages, areas of incomplete or non-existent manorialization persisted while the manorial economy underwent substantial development with changing economic conditions.

Not all manors contained all three classes of land. Typically, demesne accounted for roughly a third of the arable area, and villein holdings rather more; but some manors consisted solely of demesne, others solely of peasant holdings. The proportion of unfree and free tenures could likewise vary greatly, with more or less reliance on wage labour for agricultural work on the demesne.

The proportion of the cultivated area in demesne tended to be greater in smaller manors, while the share of villein land was greater in large manors, providing the lord of the latter with a larger supply of obligatory labour for demesne work. The proportion of free tenements was generally less variable, but tended to be somewhat greater on the smaller manors.

Manors varied similarly in their geographical arrangement: most did not coincide with a single village, but rather consisted of parts of two or more villages, most of the latter containing also parts of at least one other manor. This situation sometimes led to replacement by cash payments or their equivalents in kind of the demesne labour obligations of those peasants living furthest from the lord's estate.

As with peasant plots, the demesne was not a single territorial unit, but consisted rather of a central house with neighbouring land and estate buildings, plus strips dispersed through the manor alongside free and villein ones: in addition, the lord might lease free tenements belonging to neighbouring manors, as well as holding other manors some distance away to provide a greater range of produce.

Nor were manors held necessarily by lay lords rendering military service (or again, cash in lieu) to their superior: a substantial share (estimated by value at 17% in England in 1086) belonged directly to the king, and a greater proportion (rather more than a quarter) were held by bishoprics and monasteries. Ecclesiastical manors tended to be larger, with a significantly greater villein area than neighbouring lay manors.

The effect of circumstances on manorial economy is complex and at times contradictory: upland conditions tended to preserve peasant freedoms (livestock husbandry in particular being less labour-intensive and therefore less demanding of villein services); on the other hand, some upland areas of Europe showed some of the most oppressive manorial conditions, while lowland eastern England is credited with an exceptionally large free peasantry, in part a legacy of Scandinavian settlement.

Similarly, the spread of money economy stimulated the replacement of labour services by money payments, but the growth of the money supply and resulting inflation after 1170 initially led nobles to take back leased estates and to re-impose labour dues as the value of fixed cash payments declined in real terms.

See also

Specific:

- Latifundium

- Folwark (Poland/Lithuania)

- Baltic nobility (Estonia/Latvia)

- Heerlijkheid (Dutch manorialism)

- Junker (Prussian manorialism)

- Indian feudalism

- Patroon (17th century New Netherland)

- Seigneurial system of New France in 17th century Canada

- Shōen (Japanese Manorialism)

- Property Law in Colonial New York

General:

References

- ↑ "Feudal Society", in its modern sense was coined in Marc Bloch's 1939–40 books of the same name. Bloch (Feudal Society tr. L.A. Masnyon, 1965, vol. II p. 442) emphasised the distinction between economic manorialism which preceded feudalism and survived it, and political and social feudalism, or seigneurialism.

- ↑ Peter Sarris, "The Origins of the Manorial Economy: New Insights from Late Antiquity", The English Historical Review 119 (April 2004:279–311).

- ↑ Horn, "On the Origins of the Medieval Cloister" Gesta 12.1/2 (1973:13–52), quote p. 41.

- ↑ Andrew Jones, "The Rise and Fall of the Manorial System: A Critical Comment" The Journal of Economic History 32.4 (December 1972:938–944) p. 938; a comment on D. North and R. Thomas, "The rise and fall of the manorial system: a theoretical model", The Journal of Economic History 31 (December 1971:777–803).

- ↑ Hartwin Spenkuch, "Herrenhaus und Rittergut: Die Erste Kammer des Landtags und der preußische Adel von 1854 bis 1918 aus sozialgeschichtlicher Sicht" Geschichte und Gesellschaft, 25.3 (July – September 1999):375–403).

- ↑ C.R. Whittaker, "Circe's pigs: from slavery to serfdom in the later Roman world", Slavery and Abolition 8 (1987:87–122.

- ↑ Averil Cameron, The Mediterranean World in Late Antiquity AD 395–600, 1993:86.

- ↑ Cameron 1993:86 instances Codex Justinianus XI. 48.21.1; 50,2.3; 52.1.1.

- ↑ Payne, Stewart (2007-08-03). "Terror raids on homes of uranium ex-employee". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2010-05-12.

- ↑ http://www.londonslang.com/db/m/

- ↑ From J.H. Robinson, trans., University of Pennsylvania Translations and Reprints (1897) in Middle Ages, Volume I: pp283–284.

- Bloch, Marc (1989-11-16). Feudal Society: Vol 1: The Growth and Ties of Dependence (2 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-03916-9.

- Bloch, Marc (1989-11-16). Feudal Society: Vol 2: Social Classes and Political Organisation (2 ed.). Routledge. ISBN 0-415-03918-5.

- Boissonnade, Prosper; Eileen Power; Lynn White (1964). Life and work in medieval Europe : the evolution of medieval economy from the fifth to the fifteenth century. Harper torchbook, 1141. New York, NY: Harper & Row.

- Pirenne, Henri (1937). Economic and Social History of Medieval Europe. Harcourt Brace & Company. ISBN 0-15-627533-3.

External links

- The Register of Feudal Lords and Barons of The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland

- Archibald R. Lewis, The Development of Southern French and Catalan Society, 718–1050

- Estonian Manors Portal – the English version gives the overview of 438 best preserved historical manors in Estonia

- Medieval manors and their records Specific to the British Isles.