Seebeck coefficient

| Thermoelectric effect |

|---|

|

|

Principles

|

The Seebeck coefficient (also known as thermopower,[1] thermoelectric power, and thermoelectric sensitivity) of a material is a measure of the magnitude of an induced thermoelectric voltage in response to a temperature difference across that material, as induced by the Seebeck effect.[2] The SI unit of the Seebeck coefficient is volts per kelvin (V/K),[2] although it is more often given in microvolts per kelvin (μV/K).

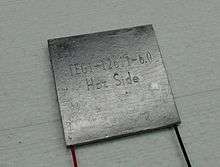

The use of materials with a high Seebeck coefficient is one of many important factors for the efficient behaviour of thermoelectric generators and thermoelectric coolers. More information about high-performance thermoelectric materials can be found in the Thermoelectric materials article. In thermocouples the Seebeck effect is used to measure temperatures, and for accuracy it is desirable to use materials with a Seebeck coefficient that is stable over time.

Physically, the magnitude and sign of the Seebeck coefficient can be approximately understood as being given by the entropy per unit charge carried by electrical currents in the material. It may be positive or negative. In conductors that can be understood in terms of independently moving, nearly-free charge carriers, the Seebeck coefficient is negative for negatively charged carriers (such as electrons), and positive for positively charged carriers (such as electron holes).

Definition

One way to define the Seebeck coefficient is the voltage built up when a small temperature gradient is applied to a material, and when the material has come to a steady state where the current density is zero everywhere. If the temperature difference ΔT between the two ends of a material is small, then the Seebeck coefficient of a material is defined as:

where ΔV is the thermoelectric voltage seen at the terminals. (See below for more on the signs of ΔV and ΔT.)

Note that the voltage shift expressed by the Seebeck effect cannot be measured directly, since the measured voltage (by attaching a voltmeter) contains an additional voltage contribution, due to the temperature gradient and Seebeck effect in the measurement leads. The voltmeter voltage is always dependent on relative Seebeck coefficients among the various materials involved.

Most generally and technically, the Seebeck coefficient is defined in terms of the portion of electric current driven by temperature gradients, as in the vector differential equation

where is the current density, is the electrical conductivity, is the voltage gradient, and is the temperature gradient. The zero-current, steady state special case described above has , which implies that the two current density terms have cancelled out and so .

Sign convention

The sign is made explicit in the following expression:

Thus, if S is positive, the end with the higher temperature has the lower voltage, and vice versa. The voltage gradient in the material will point against the temperature gradient.

The Seebeck effect is generally dominated by the contribution from charge carrier diffusion (see below) which tends to push charge carriers towards the cold side of the material until a compensating voltage has built up. As a result, in p-type semiconductors (which have only positive mobile charges, electron holes), S is positive. Likewise, in n-type semiconductors (which have only negative mobile charges, electrons), S is negative. In most conductors, however, the charge carriers exhibit both hole-like and electron-like behaviour and the sign of S usually depends on which of them predominates.

Relationship to other thermoelectric coefficients

According to the second Thomson relation (which holds for all non-magnetic materials in the absence of an externally applied magnetic field), the Seebeck coefficient is related to the Peltier coefficient by the exact relation

where is the thermodynamic temperature.

According to the first Thomson relation and under the same assumptions about magnetism, the Seebeck coefficient is related to the Thomson coefficient by

The constant of integration is such that at absolute zero, as required by Nernst's theorem.

Measurement

Relative Seebeck coefficient

In practice the absolute Seebeck coefficient is difficult to measure directly, since the voltage output of a thermoelectric circuit, as measured by a voltmeter, only depends on differences of Seebeck coefficients. This is because electrodes attached to a voltmeter must be placed onto the material in order to measure the thermoelectric voltage. The temperature gradient then also typically induces a thermoelectric voltage across one leg of the measurement electrodes. Therefore the measured Seebeck coefficient is a contribution from the Seebeck coefficient of the material of interest and the material of the measurement electrodes. This arrangement of two materials is usually called a thermocouple.

The measured Seebeck coefficient is then a contribution from both and can be written as:

Absolute Seebeck coefficient

Although only relative Seebeck coefficients are important for externally measured voltages, the absolute Seebeck coefficient can be important for other effects where voltage is measured indirectly. Determination of the absolute Seebeck coefficient therefore requires more complicated techniques and is more difficult, however such measurements have been performed on standard materials. These measurements only had to be performed once for all time, and for all materials; for any other material, the absolute Seebeck coefficient can be obtained by performing a relative Seebeck coefficient measurement against a standard material.

A measurement of the Thomson coefficient , which expresses the strength of the Thomson effect, can be used to yield the absolute Seebeck coefficient through the relation: , provided that is measured down to absolute zero. The reason this works is that is expected to decrease to zero as the temperature is brought to zero—a consequence of Nernst's theorem. Such a measurement based on the integration of was published in 1932,[3] though it relied on the interpolation of the Thomson coefficient in certain regions of temperature.

Superconductors have zero Seebeck coefficient, as mentioned below. By making one of the wires in a thermocouple superconducting, it is possible to get a direct measurement of the absolute Seebeck coefficient of the other wire, since it alone determines the measured voltage from the entire thermocouple. A publication in 1958 used this technique to measure the absolute Seebeck coefficient of lead between 7.2 K and 18 K, thereby filling in an important gap in the previous 1932 experiment mentioned above.[4]

The combination of the superconductor-thermocouple technique up to 18 K, with the Thomson-coefficient-integration technique above 18 K, allowed determination of the absolute Seebeck coefficient of lead up to room temperature. By proxy, these measurements led to the determination of absolute Seebeck coefficients for all materials, even up to higher temperatures, by a combination of Thomson coefficient integrations and thermocouple circuits.[5]

The difficulty of these measurements, and the rarity of reproducing experiments, lends some degree of uncertainty to the absolute thermoelectric scale thus obtained. In particular, the 1932 measurements may have incorrectly measured the Thomson coefficient over the range 20 K to 50 K. Since nearly all subsequent publications relied on those measurements, this would mean that all of the commonly used values of absolute Seebeck coefficient (including those shown in the figures) are too low by about 0.3 μV/K, for all temperatures above 50 K.[6]

Seebeck coefficients for some common materials

In the table below are Seebeck coefficients at room temperature for some common, nonexotic materials, measured relative to platinum.[7] The Seebeck coefficient of platinum itself is approximately −5 μV/K at room temperature,[8] and so the values listed below should be compensated accordingly. For example, the Seebeck coefficients of Cu, Ag, Au are 1.5 μV/K, and of Al −1.5 μV/K. The Seebeck coefficient of semiconductors very much depends on doping, with generally positive values for p doped materials and negative values for n doping.

| Material | Seebeck coefficient relative to platinum (μV/K) |

|---|---|

| Selenium | 900 |

| Tellurium | 500 |

| Silicon | 440 |

| Germanium | 330 |

| Antimony | 47 |

| Nichrome | 25 |

| Molybdenum | 10 |

| Cadmium, tungsten | 7.5 |

| Gold, silver, copper | 6.5 |

| Rhodium | 6.0 |

| Tantalum | 4.5 |

| Lead | 4.0 |

| Aluminium | 3.5 |

| Carbon | 3.0 |

| Mercury | 0.6 |

| Platinum | 0 (definition) |

| Sodium | -2.0 |

| Potassium | -9.0 |

| Nickel | -15 |

| Constantan | -35 |

| Bismuth | -72 |

Physical factors that determine the Seebeck coefficient

A material's temperature, crystal structure, and impurities influence the value of thermoelectric coefficients. The Seebeck effect can be attributed to two things:[9] charge-carrier diffusion and phonon drag.

Charge carrier diffusion

On a fundamental level, an applied voltage difference refers to a difference in the thermodynamic chemical potential of charge carriers, and the direction of the current under a voltage difference is determined by the universal thermodynamic process in which (given equal temperatures) particles flow from high chemical potential to low chemical potential. In other words, the direction of the current in Ohm's law is determined via the thermodynamic arrow of time (the difference in chemical potential could be exploited to produce work, but is instead dissipated as heat which increases entropy). On the other hand, for the Seebeck effect not even the sign of the current can be predicted from thermodynamics, and so to understand the origin of the Seebeck coefficient it is necessary to understand the microscopic physics.

Charge carriers (such as thermally excited electrons) constantly diffuse around inside a conductive material. Due to thermal fluctuations, some of these charge carriers travel with a higher energy than average, and some with a lower energy. When no voltage differences or temperature differences are applied, the carrier diffusion perfectly balances out and so on average one sees no current: . A net current can be generated by applying a voltage difference (Ohm's law), or by applying a temperature difference (Seebeck effect). To understand the microscopic origin of the thermoelectric effect, it is useful to first describe the microscopic mechanism of the normal Ohm's law electrical conductance—to describe what determines the in . Microscopically, what is happening in Ohm's law is that higher energy levels have a higher concentration of carriers per state, on the side with higher chemical potential. For each interval of energy, the carriers tend to diffuse and spread into the area of device where there are less carriers per state of that energy. As they move, however, they occasionally scatter dissipatively, which re-randomizes their energy according to the local temperature and chemical potential. This dissipation empties out the carriers from these higher energy states, allowing more to diffuse in. The combination of diffusion and dissipation favours an overall drift of the charge carriers towards the side of the material where they have a lower chemical potential.[10]:Ch.11

For the thermoelectric effect, now, consider the case of uniform voltage (uniform chemical potential) with a temperature gradient. In this case, at the hotter side of the material there is more variation in the energies of the charge carriers, compared to the colder side. This means that high energy levels have a higher carrier occupation per state on the hotter side, but also the hotter side has a lower occupation per state at lower energy levels. As before, the high-energy carriers diffuse away from the hot end, and produce entropy by drifting towards the cold end of the device. However, there is a competing process: at the same time low-energy carriers are drawn back towards the hot end of the device. Though these processes both generate entropy, they work against each other in terms of charge current, and so a net current only occurs if one of these drifts is stronger than the other. The net current is given by , where (as shown below) the thermoelectric coefficient depends literally on how conductive high-energy carriers are, compared to low-energy carriers. The distinction may be due to a difference in rate of scattering, a difference in speeds, a difference in density of states, or a combination of these effects.

Mott formula

The processes described above apply in materials where each charge carrier sees an essentially static environment so that its motion can be described independently from other carriers, and independent of other dynamics (such as phonons). In particular, in electronic materials with weak electron-electron interactions, weak electron-phonon interactions, etc. it can be shown in general that the linear response conductance is

and the linear response thermoelectric coefficient is

where is the energy-dependent conductivity, and is the Fermi–Dirac distribution function. These equations are known as the Mott relations, of Sir Nevill Francis Mott.[11] The derivative is a function peaked around the chemical potential (Fermi level) with a width of approximately . The energy-dependent conductivity (a quantity that cannot actually be directly measured — one only measures ) is calculated as where is the electron diffusion constant and is the electronic density of states (in general, both are functions of energy).

In materials with strong interactions, none of the above equations can be used since it is not possible to consider each charge carrier as a separate entity. The Wiedemann–Franz law can also be exactly derived using the non-interacting electron picture, and so in materials where the Wiedemann–Franz law fails (such as superconductors), the Mott relations also generally tend to fail.[12]

The formulae above can be simplified in a couple of important limiting cases:

Mott formula in metals

In semimetals and metals, where transport only occurs near the Fermi level and changes slowly in the range , one can perform a Sommerfeld expansion , which leads to

This expression is sometimes called "the Mott formula", however it is much less general than Mott's original formula expressed above.

In the Drude–Sommerfeld degenerate free electron gas with scattering, the value of is of order , where is the Fermi temperature, and so a typical value of the Seebeck coefficient in the Fermi gas is (the prefactor varies somewhat depending on details such as dimensionality and scattering). In highly conductive metals the Fermi temperatures are typically around 104 – 105 K, and so it is understandable why their absolute Seebeck coefficients are only of order 1 – 10 μV/K at room temperature. Note that whereas the free electron gas is expected to have a negative Seebeck coefficient, real metals actually have complicated band structures and may exhibit positive Seebeck coefficients (examples: Cu, Ag, Au).

The fraction in semimetals is sometimes calculated from the measured derivative of with respect to some energy shift induced by field effect. This is not necessarily correct and the estimate of can be incorrect (by a factor of two or more), since the disorder potential depends on screening which also changes with field effect.[13]

Mott formula in semiconductors

In semiconductors at low levels of doping, transport only occurs far away from the Fermi level. At low doping in the conduction band (where , where is the minimum energy of the conduction band edge), one has . Approximating the conduction band levels' conductivity function as for some constants and ,

whereas in the valence band when and ,

The values of and depend on material details; in bulk semiconductor these constants range between 1 and 3, the extremes corresponding to acoustic-mode lattice scattering and ionized-impurity scattering.[14]

In extrinsic (doped) semiconductors either the conduction or valence band will dominate transport, and so one of the numbers above will give the measured values. In general however the semiconductor may also be intrinsic in which case the bands conduct in parallel, and so the measured values will be

The highest Seebeck coefficient is obtained when the semiconductor is lightly doped, however a high Seebeck coefficient is not necessarily useful. For thermoelectric power devices (coolers, generators) it is more important to maximize the thermoelectric power factor ,[15] or the thermoelectric figure of merit, and the optimum generally occurs at high doping levels.[16]

Phonon drag

Phonons are not always in local thermal equilibrium; they move against the thermal gradient. They lose momentum by interacting with electrons (or other carriers) and imperfections in the crystal. If the phonon-electron interaction is predominant, the phonons will tend to push the electrons to one end of the material, hence losing momentum and contributing to the thermoelectric field. This contribution is most important in the temperature region where phonon-electron scattering is predominant. This happens for

where is the Debye temperature. At lower temperatures there are fewer phonons available for drag, and at higher temperatures they tend to lose momentum in phonon-phonon scattering instead of phonon-electron scattering. This region of the thermopower-versus-temperature function is highly variable under a magnetic field.

Relationship with entropy

The Seebeck coefficient of a material corresponds thermodynamically to the amount of entropy "dragged along" by the flow of charge inside a material; it is in some sense the entropy per unit charge in the material.[17]

Superconductors

Superconductors have zero Seebeck coefficient, because the current-carrying charge carriers (Cooper pairs) have no entropy; hence, the transport of charge carriers (the supercurrent) has zero contribution from any temperature gradient that might exist to drive it.

References

- ↑ Thermopower is a misnomer as this quantity does not actually express a power quantity: Note that the unit of thermopower (V/K) is different from the unit of power (watts).

- 1 2 Concepts in Thermal Physics, by Katherine M. Blundell Weblink through Google books

- ↑ Borelius, G.; Keesom, W. H.; Johannson, C. H.; Linde, J. O. (1932). "Establishment of an Absolute Scale for the Thermo-electric Force". Proceedings of the Royal Academy of Sciences at Amsterdam. 35 (1): 10.

- ↑ Christian, J. W.; Jan, J.-P.; Pearson, W. B.; Templeton, I. M. (1958). "Thermo-Electricity at Low Temperatures. VI. A Redetermination of the Absolute Scale of Thermo-Electric Power of Lead". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 245 (1241): 213. Bibcode:1958RSPSA.245..213C. doi:10.1098/rspa.1958.0078.

- ↑ Cusack, N.; Kendall, P. (1958). "The Absolute Scale of Thermoelectric Power at High Temperature". Proceedings of the Physical Society. 72 (5): 898. Bibcode:1958PPS....72..898C. doi:10.1088/0370-1328/72/5/429.

- ↑ Roberts, R. B. (1986). "Absolute scales for thermoelectricity". Measurement. 4 (3): 101–103. doi:10.1016/0263-2241(86)90016-3.

- ↑ The Seebeck Coefficient, Electronics Cooling.com (accessed 2013-Feb-01)

- ↑ Moore, J. P. (1973). "Absolute Seebeck coefficient of platinum from 80 to 340 K and the thermal and electrical conductivities of lead from 80 to 400 K". Journal of Applied Physics. 44 (3): 1174. Bibcode:1973JAP....44.1174M. doi:10.1063/1.1662324.

- ↑ Kong, Ling Bing. Waste Energy Harvesting. Springer. pp. 263–403. ISBN 978-3-642-54634-1.

- ↑ Datta, Supriyo (2005). Quantum Transport: Atom to Transistor. Cambridge University Presss. ISBN 9780521631457.

- ↑ Cutler, M.; Mott, N. (1969). "Observation of Anderson Localization in an Electron Gas". Physical Review. 181 (3): 1336. Bibcode:1969PhRv..181.1336C. doi:10.1103/PhysRev.181.1336.

- ↑ Jonson, M.; Mahan, G. (1980). "Mott's formula for the thermopower and the Wiedemann-Franz law". Physical Review B. 21 (10): 4223. Bibcode:1980PhRvB..21.4223J. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.21.4223.

- ↑ Hwang, E. H.; Rossi, E.; Das Sarma, S. (2009). "Theory of thermopower in two-dimensional graphene". Physical Review B. 80 (23). arXiv:0902.1749

. Bibcode:2009PhRvB..80w5415H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.80.235415.

. Bibcode:2009PhRvB..80w5415H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.80.235415. - ↑ Semiconductor Physics: An Introduction, Karlheinz Seeger

- ↑ http://journals.aps.org/prb/abstract/10.1103/PhysRevB.64.241104

- ↑ G. Jeffrey Snyder, "Thermoelectrics". http://www.its.caltech.edu/~jsnyder/thermoelectrics/

- ↑ Bulusu, A.; Walker, D. G. (2008). "Review of electronic transport models for thermoelectric materials". Superlattices and Microstructures. 44: 1. Bibcode:2008SuMi...44....1B. doi:10.1016/j.spmi.2008.02.008.