Seanad Éireann

| Seanad Éireann Senate of Ireland | |

|---|---|

| 25th Seanad | |

| |

| Type | |

| Type |

Upper house of the Oireachtas |

| Leadership | |

Opposition Leader | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 60 |

| |

Political groups |

|

| Elections | |

Last election | 24 April 2016 |

| Meeting place | |

| |

|

Seanad chamber Leinster House, Dublin | |

| Website | |

|

www | |

Seanad Éireann (/ˌʃænəd, -ð ˈɛərən/;[1] Senate of Ireland) is the upper house of the Oireachtas (the Irish legislature), which also comprises the President of Ireland and Dáil Éireann (the lower house). It is commonly called the Seanad or Senate and its members senators (seanadóirí in Irish, singular: seanadóir). Unlike Dáil Éireann, it is not directly elected but consists of a mixture of members chosen by various methods. Its powers are much weaker than those of the Dáil and it can only delay laws with which it disagrees, rather than veto them outright. It has been located, since its establishment, in Leinster House.

Composition

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of the Republic of Ireland |

|

Judiciary |

|

Administrative geography |

Under Article 18 of the Constitution, Seanad Éireann consists of sixty senators, composed as follows:

- Eleven nominated by the Taoiseach (prime minister).

- Six elected by the graduates of certain Irish universities:

- Three by graduates of the University of Dublin.

- Three by graduates of the National University of Ireland.

- 43 elected from five special panels of nominees (known as Vocational Panels) by an electorate consisting of TDs (member of Dáil Éireann), outgoing senators and members of city and county councils. Nomination is restrictive for the panel seats with only Oireachtas members and designated 'nominating bodies' entitled to nominate. Each of the five panels consists, in theory, of individuals possessing special knowledge of, or experience in, one of five specific fields. In practice the nominees are party members, often, though not always, failed or aspiring Dáil candidates:

- Seven seats on the Administrative Panel: Public administration and social services (including the voluntary sector).

- Eleven seats on the Agricultural Panel: Agriculture and the fisheries.

- Five seats on the Cultural and Educational Panel: Education, the arts, the Irish language and Irish culture and literature.

- Nine seats on the Industrial and Commercial Panel: Industry and commerce (including engineering and architecture).

- Eleven seats on the Labour Panel: Labour (organised or otherwise).

The general election for the Seanad must occur not later than 90 days after the dissolution of Dáil Éireann. The election occurs under the system of proportional representation by means of the single transferable vote (in the panel constituencies each vote counts as 1000, allowing fractions of votes to be more easily transferred). Membership is open to all Irish citizens over 21, but a senator cannot also be a member of Dáil Éireann. However, as stated above, nomination to vocational panel seats is restricted; nomination in the University constituencies requires signatures of 10 graduates.

In the case of vacancies in the Vocational Panels, the electorate in the by-election consists of Oireachtas members only.[2] Vacancies to the university seats are filled by the full electorate in that constituency.

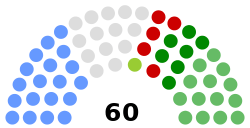

Members of the 25th Seanad (2016-present)

| Party | Senators | |

|---|---|---|

| Fine Gael | 19 | |

| Fianna Fáil | 14 | |

| Sinn Féin | 7 | |

| Labour Party | 5 | |

| Green Party | 1 | |

| Independent | 14 | |

| Total | 60 | |

As well as the political party groupings, there are two technical groupings of independents in the current Seanad - The Civil Engagement group (which includes Green Party Senator Grace O'Sullivan) and the Independent Senators group, which contains all other independent senators bar Senator David Norris

Powers

The powers of Seanad Éireann are modelled loosely on those of the British House of Lords. It was intended to play an advisory and revising role rather than to be the equal of the popularly elected Dáil. While notionally every Act of the Oireachtas must receive its assent, it can only delay rather than veto decisions of the Dáil. In practice, however, the Seanad has an in-built government majority due to the Taoiseach's nominees. The constitution imposes the following specific limitations on the powers of the Seanad:

- In the event that a bill approved by Dáil Éireann has not received the assent of the Seanad within 90 days, the Dáil may, within a further 180 days, resolve that the measure is "deemed" to have been approved by the Seanad. This has only occurred twice since 1937, once in 1959 when the Seanad rejected the Third Amendment to the Constitution Bill 1958 and again in 1964 when they rejected the Pawnbrokers Bill 1964. In both instances the Dáil passed the requisite motion deeming the legislation to have been passed.[3]

- A money bill, such as the budget, may be deemed to have been approved by the Seanad after 21 days.

- In the case of an urgent bill, the time that must have expired before it can be deemed to have been approved by the Seanad may be abridged by the Government (cabinet) with the concurrence of the President (this does not apply to bills to amend the constitution).

- The fact that 11 senators are appointed by the Taoiseach usually ensures that the Government, which must have the support of the Dáil, also enjoys a majority in the Seanad.

The constitution does, however, grant to the Seanad certain means by which it may defend its prerogatives against an overly zealous Dáil:

- The Seanad may, by a resolution, ask the President to appoint a Committee of Privileges to adjudicate as to whether or not a particular bill is a money bill. The President may, however, refuse this request. This procedure has not initiated since the re-establishment of the Seanad under the current Constitution in 1937.[4]

- If a majority of senators and at least one-third of the members of the Dáil present a petition to the President stating that a bill is of great "national importance" the President can decline to sign the bill until it has been 'referred to the people'. This means that he or she can refuse to sign it until it has been approved either in an ordinary referendum or by the Dáil after it has reassembled after a general election.

Activities

Seanad Éireann adopts its own standing orders and appoints its president, known as the Cathaoirleach ("Chair"), and a Leader of the Seanad. The Seanad establishes its own standing committees and select committee; senators also participate, along with TDs (members of the Dáil) in joint committees of the Oireachtas. A maximum of two senators may be ministers in the Government.

Standing committees

- Committee on Administration

- Committee on Consolidation Bills

- Committee of Selection

- Committee on Procedure and Privileges

- Sub-committee on Compellability

- Committee on Members' Interests of Seanad Éireann

Select committees

- Select committee on Communications, Natural Resources and Agriculture

- Select committee on Environment, Transport, Culture and the Gaeltacht

- Select committee on European Union Affairs

- Select committee on Foreign Affairs and Trade

- Select committee on Finance, Public Expenditure and Reform

- Select committee on Health and Children

- Select committee on the Implementation of the Good Friday Agreement

- Select committee on Investigations, Oversight and Petitions

- Select committee on Jobs, Social Protection and Education

- Select committee on Justice, Defence and Equality

Historical origins

Early precursors

The first parliamentary upper house in Ireland was the House of Lords of the Parliament of Ireland. Like its British counterpart, this house consisted of hereditary nobles and bishops. After the abolition of the Irish Parliament under the Act of Union of 1800 no parliament existed in Ireland until the twentieth century.

In 1919 Irish nationalists established a legislature called Dáil Éireann but this body was unicameral and so had no upper house. In 1920 the Parliament of Southern Ireland was established by British law with an upper house called the Senate. The Senate of Southern Ireland consisted of a mixture of Irish peers and government appointees. The Senate convened in 1921 but was boycotted by Irish nationalists and so never became fully operational. It was formally abolished with the establishment of the Irish Free State in 1922 but a number of its members were soon appointed to the new Free State senate.

Free State Seanad Éireann (1922–1936)

The name Seanad Éireann was first used as the title of the upper house of the Oireachtas of the Irish Free State. The first Seanad consisted of a mixture of members appointed by the President of the Executive Council and members indirectly elected by the Dáil, and W. T. Cosgrave agreed to use his appointments to grant extra representation to the state's Protestant minority. It was intended that eventually the entire membership of the Seanad would be directly elected by the public but after only one election, in 1925, this system was abandoned in favour of a form of indirect election. The Free State Seanad was abolished entirely in 1936 after it delayed some Government proposals for constitutional changes.

Constitution of Ireland (Since 1937)

The modern Seanad Éireann was established by the Constitution of Ireland in 1937. When this document was adopted it was decided to preserve the titles of Oireachtas, for the two houses of the legislature, in conjunction with the President, Dáil Éireann for the lower house, and Seanad Éireann for the upper house, the latter having been used during the Irish Free State. This new Seanad was considered to be the direct successor of the Free State Seanad and so the first Seanad convened under the new constitution was referred to as the "Second Seanad".

The new system of Vocational Panels used to nominate candidates for the Seanad was inspired by Roman Catholic social teaching of the 1930s, and in particular the 1931 papal encyclical Quadragesimo anno. In this document Pope Pius XI argued that the Marxist concept of class conflict should be replaced with a vision of social order based on the co-operation and interdependence of society's various vocational groups.

Calls for reform

Since 1928 twelve separate official reports have been published on reform of the Seanad.[5] In the past the Progressive Democrats called for its outright abolition; however, they have benefited from the Taoiseach's right to select 11 Senators. Today Fine Gael, Labour, Sinn Féin and the Socialist Party would like to see the Seanad abolished.[6] The post-1937 body has been criticised on a number of grounds, including claims that it is weak and dominated by the Government of the day. There are also allegations of patronage in the selection of its members, with senators often being close allies of the Taoiseach or candidates who have failed to be elected to the Dáil. Many senators have subsequently been elected as TDs.

Irish universities have a long tradition of electing independent candidates. Some, like the pressure group Graduate Equality, argue that the franchise for electing university senators should be extended to the graduates of all third level institutions. Others believe that this does not go far enough and that at least some portion of the Seanad should be directly elected by all adult citizens. Calls have also been made for the Seanad to be used to represent Irish emigrants or the people of Northern Ireland. In 1999 the Reform Movement called for some of the Taoiseach's nominations to be reserved for members of the Irish-British minority, and other minorities such as members of the Travelling Community and recently arrived immigrants. The Seventh Amendment in 1979 altered the provisions of Article 18.4 to allow for a redistribution of the university seats to any other institutes of higher education in the state, although no change has in fact taken place since then.

In May 2011, The Sunday Business Post commented that "university representation is a system so bizarre that it is rivalled only by the hereditary peerages in the British House of Lords as an anachronism in modern democracies."[7]

In the past, Taoisigh often included respected people from Northern Ireland among their eleven nominees, such as the peace campaigner Gordon Wilson, Sam McAughtry, John Robb, Seamus Mallon of the SDLP, and Maurice Hayes. Benjamin Guinness (Lord Iveagh) sat as a nominated Senator from 1973 to 1977 while was also a member of the House of Lords.

Proposed abolition

In October 2009, Fine Gael leader Enda Kenny stated his intention that a Fine Gael government would abolish the Seanad, and along with reducing the number of TDs by 20, it would "save an estimated €150m over the term of a Dáil."[8] During the 2011 election campaign, Labour and Sinn Féin also promised to abolish the Seanad,[9][10] while Fianna Fáil supported a referendum on the issue.[11] The programme of the Fine Gael–Labour coalition, which came to power at the election, sought to abolish the Seanad as part of a broader programme of constitutional reform,[12] but lost a referendum on the matter in October 2013 by 51.7% to 48.3%.

Notable former senators

- Michael D. Higgins

- Noël Browne

- Robert Malachy Burke

- Éamon de Buitléar

- James Dooge

- Garret FitzGerald

- Brian Friel

- Valerie Goulding

- Edward Haughey, Baron Ballyedmond

- Maurice Hayes

- Tras Honan

- Douglas Hyde

- Benjamin Guinness, 3rd Earl of Iveagh

- Cecil Lavery

- Edward Pakenham, 6th Earl of Longford

- Sam McAughtry

- Peadar Toner Mac Fhionnlaoich

- Catherine McGuinness

- John Magnier

- Seamus Mallon

- Maurice George Moore

- Conor Cruise O'Brien

- Mary Robinson

- Bríd Rodgers

- James Ryan

- T. K. Whitaker

- Gordon Wilson

See also

- Bicameralism

- The Civil Engagement group

- Politics of the Republic of Ireland

- Records of members of the Oireachtas

- Senate

- University constituency

References

- ↑ "Seanad: definition of Seanad in Oxford dictionary (British & World English). Meaning, pronunciation and origin of the word". Oxford Language Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. 2013. Retrieved 30 November 2013.

- ↑ "Ryan 'very unlikely' to accept Seanad seat". Irish Independent. 15 June 2009. Retrieved 17 June 2009.

- ↑ Hogan, Gerard; Whyte, Gerry (2003). JM Kelly: The Irish Constitution (4th ed.). Bloomsbury. p. 396. ISBN 9781845923662.

- ↑ Forde, Michael (2004). Constitutional law (2nd ed.). Dublin: First Law. ISBN 1904480195.

- ↑ Joint Oireachtas Committee on the Constitution (16 May 1928). "Report and Proceedings – the constitution and powers of, and methods of election to, Seanad Éireann". Oireachtas. Retrieved 22 August 2012.

- ↑ "Kenny defends Seanad plan". The Irish Times. 19 October 2009. Retrieved 19 October 2009.

- ↑ Government parties can decide shape of Seanad’s last hurrah

- ↑ "Kenny: FG would slash TD numbers, abolish Seanad". BreakingNews.ie. 17 October 2009.

- ↑ "Labour calls for Seanad to be abolished". RTÉ News. 4 January 2011.

- ↑ "Government lagging behind public on Seanad abolition – Doherty". Sinn Féin. 3 January 2011.

- ↑ "Fianna Fáil U-turn on Seanad looks to have sealed fate of Upper House". The Irish Times. 3 January 2011.

- ↑ "Programme for Government" (PDF). Department of Public Expenditure and Reform. March 2010. p. 17. Retrieved 30 December 2013.

External links

- Report on Reform of the Seanad – Report of Seanad Éireann Committee on Procedure and Privileges Sub-Committee on Seanad Reform, from official Oireachtas website.