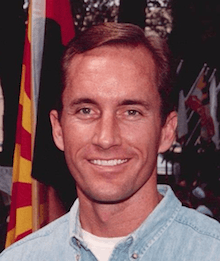

Scott Bundgaard

| Hon. Scott Bundgaard | |

|---|---|

| |

| Member of the Arizona Senate from the 4th district | |

|

In office January 10, 2011 – January 6, 2012 | |

| Succeeded by | Judy Burges |

| Member of the Arizona Senate from the 19th district | |

|

In office January 13, 1997 – January 13, 2003 | |

| Preceded by | Jan Brewer |

| Member of the Arizona House of Representatives from the 19th district | |

|

In office January 9, 1995 – January 13, 1997 | |

| Preceded by |

Nancy Wessel John Keegan |

| Succeeded by | Roberta Voss |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

January 11, 1968 Oklahoma City, Oklahoma |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse(s) | Stephanie |

| Alma mater | Grand Canyon University, Thunderbird School of Global Management |

| Website | http://www.scottbundgaard.com |

Scott Bundgaard is a Republican politician who served in the Arizona House of Representatives and in the Arizona State Senate. Bundgaard served as Chairman of the Senate Finance Committee [1] and was later elected as Majority Leader of the Arizona State Senate.[2]

Early life and education

Scott Bundgaard was born in Oklahoma City, OK, while his parents were moving to Phoenix, Arizona from Omaha, Nebraska. Scott graduated with a BS degree from Grand Canyon University in 1990. Scott received his MBA in 2005 from Thunderbird School of Global Management.

Personal life

Scott married Stephanie Moore in July 2013 and the couple lives in Peoria, AZ.

Political career

Scott was elected as the Majority Leader of the Arizona State Senate in a 17-4 vote. Two months after becoming Majority Leader, Bundgaard was involved in a physical altercation with his then girlfriend. Democrats and Republicans in the State Senate demanded that Bundgaard step down as Majority Leader, but the Republican caucus refused to vote to replace him.[3] One week later, Bundgaard asked for a vote from his colleagues and was removed as Majority Leader on March 15, 2011 by a vote of 13-11 of the Senate Republican caucus. Bundgaard said, "I serve at the pleasure of the caucus and have emphasized that fact to my caucus for the past two weeks," Bundgaard told Reuters. "I did not want my personal life, which has been sensationalized in the media, to be a distraction at this critical time."[4]

Bundgaard had previously served in the Arizona State Senate for six years (1997–2003)

- In 1996, he won the Primary Election with 53.66% of the vote against two other candidates.[5]

- In 1998, he ran unopposed.[6]

- In 2000, he won the Primary Election with 66.83% of the against one candidate.[7]

Bundgaard also served in the Arizona House of Representatives for two years (1995-1997)

- In 1994, he won the Primary Election with 43.15% of the vote, splitting the vote with another candidate for the two House seats.[8]

Scott received the "Friend of the Taxpayer" Award every year for the seven years he served in the state legislature, according to the Arizona Federation of Taxpayers Associations (AFTA). AFTA is a statewide non-profit, non-partisan organization that rates elected officials according to their voting record.[9]

In 2000, Bundgaard was a prime sponsor of Senate Bill 1220[10] which created the Arizona Sports and Tourism Authority to build taxpayer-funded stadiums for National Football League and major league baseball teams and youth sports. Arizona voters approved the project.[11]

He ran unsuccessfully in 2002 for the Republican nomination for the United States House of Representatives in Arizona's second congressional district, receiving only 16.1% of the vote among a field of seven candidates.[12]

Controversies

Domestic Violence Allegation

On the evening of February 25, 2011 police responded to a call regarding a man, later identified as Bundgaard, pulling a woman out of a car in Phoenix Arizona.[13] [14] [15] Both Bundgaard and his then girlfriend, Aubry Ballard, showed signs of a physical altercation.[13] Both were taken into custody at the roadside, but only his girlfriend was arrested and charged with domestic violence assault. Police who responded to the call said Bundgaard was not arrested because he claimed he had immunity while the Arizona legislature was in session. [15] [16] On June 10, 2011 he was served with a summons[17] and complaint[18] for assault (ARS 13-1203A), endangerment (ARS 13-1201A), and domestic violence (ARS 13-3601A).

On August 16, 2011, after lengthy negotiations between both the Senator's attorneys and prosecutors, he pleaded no contest and agreed to participate in domestic violence classes. [19] [20] He was ordered to pay his victim criminal restitution.[19]

Other Controversies

He was the prime sponsor of SB 1412 in 2000, which was a bill that died in committee.[21] Bundgaard was later tasked by Governor Jane Hull to lead a committee to dissolve a controversial alternative fuels program that cost the Arizona taxpayers over $100 million.[22] As a legislator who chaired that committee, he personally went through the alt fuels program in an attempt to buy five vehicles to demonstrate the lunacy and ineffectiveness of the program.[22]

In 1995, Bundgaard introduced a bill that would have allowed the death penalty to be applied to drug dealers.[23]

In 1999, Bundgaard intervened on behalf of a dump owner in West Valley to prevent further litigation for illegal practices and reduce the owner's legal liability.[24]

He was fined $3,500 by the Federal Elections Commission for failure to timely file a campaign finance report during the 2002 congressional campaign.[25]

Scott Bundgaard has a long history of civil litigation.[26] In 1986, he was convicted of one count of third degree burglary. After two years, his class four felony conviction was "expunged."[27]

In 2003, the brokerage company he worked for was sued by a client for a loss of funds. The client was upset that he lost money that he had placed into a technology mutual fund. A settlement agreement was reached. Bundgaard sold his book of business several years later and voluntarily left the securities industry.[27]

In 2006, he was married in a covenant marriage but his wife had to call the police during the honeymoon, because she wanted to return home to her parents.[28]

In December 2012 Bundgaard filed a $10,000,000 lawsuit against the City of Phoenix alleging that three police officers, the mayor of Phoenix, the chief of police, five civilian witnesses and the victim of his domestic violence attack conspired to defame his character.[29] The case was transferred to federal district court. In March 2014, Bundgaard requested the lawsuit be dismissed without a judgement, and ultimately received nothing from the City of Phoenix.[30]

References

- ↑ http://www.azleg.state.az.us/committe/44leg/sfin.htm

- ↑ http://www.azleg.gov/MembersPage.asp?Member_ID=4&Legislature=50&Session_ID=102 "Scott Bundgaard", Arizona State Legislature, Retrieved on 13 September 2016.

- ↑ http://azcapitoltimes.com/news/2011/03/08/bundgaard-remains-as-ariz-senate-majority-leader/

- ↑ http://www.reuters.com/article/us-arizona-lawmaker-idUSTRE72F0DB20110316

- ↑ http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=272473

- ↑ http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=272472

- ↑ http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=272469

- ↑ http://www.ourcampaigns.com/RaceDetail.html?RaceID=278489

- ↑ http://www.ourcampaigns.com/CandidateDetail.html?CandidateID=2764

- ↑ Bill status Overview

- ↑ History Behind AZSTA

- ↑ http://www.azsos.gov/election/2002/Primary/Canvass2002PE.pdf

- 1 2 State Sen. Bundgaard involved in domestic violence incident, Arizona Central. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Bundgaard involved in domestic violence incident, Arizona Capitol Times, Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- 1 2 Immunity prevents arrest of Arizona lawmaker after freeway fight, CNN. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ A Legal Privilege That Some Lawmakers See Broadly, New York Times. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ http://www.azcentral.com/ic/pdf/arizona-senator-bundgaard-summons.pdf

- ↑ http://www.azcentral.com/ic/pdf/arizona-senator-bundgaard-complaint.pdf

- 1 2 Top Surprise judge’s goals: Communication, fairness, Arizona Central. Retrieved 13 September 2016.

- ↑ Bundgaard pleads no contest to endangerment Arizona Family. Retrieved 16 September 2016.

- ↑ http://www.azleg.gov//FormatDocument.asp?inDoc=/legtext/44leg/2r/bills/sb1412o.asp&Session_ID=63

- 1 2 http://www.azleg.state.az.us/legtext/44leg/7s/comm_min/senate/1129%20fin.doc.htm

- ↑ "Death for drug dealers proposed" (newspaper) (Thursday, September 14, 1995). Arizona Republic. p. 4.

- ↑ http://www.phoenixnewtimes.com/news/scott-free-6421356

- ↑ http://eqs.fec.gov/eqsdocsADR/24092550063.pdf#search=AF%20982

- ↑ http://www.superiorcourt.maricopa.gov/docket/CivilCourtCases/caseSearchResults.asp?lastName=Bundgaard&FirstName=Scott&bName=

- 1 2 http://brokercheck.finra.org/Individual/Summary/2934901

- ↑ http://archive.azcentral.com/news/election/azelections/articles/20110308arizona-senator-scott-bundgaard-failed-marriage.html

- ↑ "Bundgaard files lawsuit against Phoenix". Arizona Republic. 2012-12-20. Retrieved 2012-12-22.

- ↑ http://www.azcentral.com/story/news/local/phoenix/2014/03/17/arizona-lawmaker-scott-bundgaard-fight-lawsuit/6544505/