SOAS, University of London

Arms of SOAS | |

| Motto | Knowledge is Power |

|---|---|

| Type | Public |

| Established | 1916 |

| Endowment | £35.4 million[1] |

| Chancellor | Anne, Princess Royal (University of London) |

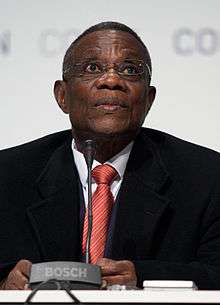

| President | Graça Machel |

| Director | Baroness Valerie Amos |

| Students | 5,910 (2014/15)[2] |

| Undergraduates | 3,015 (2014/15)[2] |

| Postgraduates | 2,890 (2014/15)[2] |

| Location | London, United Kingdom |

| Campus | Urban |

| Mascot | Arabian Camel and Asian Elephant |

| Affiliations |

University of London ACU |

| Website |

www |

| |

SOAS, University of London (The School of Oriental and African Studies),[3] is a public research university in London, England, and a constituent college of the University of London. Founded in 1916, it is regarded as one of the leading universities in Europe. SOAS has produced several heads of states, government ministers, diplomats, Supreme Court judges, a Nobel Peace Prize Laureate and many other notable leaders around the world.

Located in the heart of Bloomsbury in central London, SOAS is recognised as the leading institution for the study of Asia, Africa and the Middle East and is ranked amongst the top universities in Britain.[4][5] It specialises in the humanities, languages and social sciences of Asia, Africa and the Middle East. It is home to the SOAS School of Law. SOAS offers around 350 undergraduate bachelor's degree combinations, over 100 one-year master's degrees and PhD programmes in nearly every department.

History

Origins

The School of Oriental Studies was founded in 1916 at 2 Finsbury Circus, London, the then premises of the London Institution. The school received its royal charter on 5 June 1916 and admitted its first students on 18 January 1917. The school was formally inaugurated a month later on 23 February 1917 by King George V. Among those in attendance were Earl Curzon of Kedleston, formerly Viceroy of India, and other cabinet officials.[6]

The School of Oriental Studies was founded by the British state as an instrument to strengthen Britain's political, commercial and military presence in Asia and Africa.[7] It would do so by providing instruction to colonial administrators (Colonial Service and Indian Civil Service),[7] commercial managers and military officers, but also to missionaries, doctors and teachers, in the language of that part of Asia or Africa to which each was being posted, together with an authoritative introduction to the customs, religion, laws and history of the people whom they were to govern or among whom they would be working.[7]

The school's founding mission was to advance British scholarship, science and commerce in Africa and Asia and to provide London University with a rival to the famous Oriental schools of Berlin, Petrograd and Paris.[8] The school immediately became integral in training British administrators, colonial officials and spies for overseas postings across the British Empire. Africa was added to the school's name in 1938.

Second World War

For sometime in the mid-1930s, prior to moving to its current location at Thornhaugh Street, Bloomsbury, the school was located at Vandon House, Vandon Street, London SW1, with the library located at Clarence House. Its move to new premises in Bloomsbury was held up by delays in construction and the half-completed building took a hit during the Blitz in September 1940. With the onset of the Second World War, many University of London colleges were evacuated from London in 1939 and billeted on universities all over the provinces.[9] The School was, on the Government's advice, transferred to Christ's College, Cambridge.[10]

In 1940, when it became apparent that a return to London was possible, the school returned to the city and was housed for some months in eleven rooms at Broadway Court, 8 Broadway, London SW1. In 1942, the War Office joined with the school's Japanese department to help alleviate the shortage in Japanese linguists. State scholarships were offered to select grammar and public school boys to train as military translators and intelligence officers. Lodged at Dulwich College in south London, the students became affectionately known as the Dulwich boys.[11]

Bletchley Park, the headquarters of the Government Code and Cypher School (GC&CS), was concerned about the slow pace of the SOAS, so they started their own Japanese-language courses at Bedford in February 1942. The courses were directed by army cryptographer, Col. John Tiltman, and retired Royal Navy officer, Capt. Oswald Tuck.[12]

1945 to present

In recognition of SOAS's role during the war, the 1946 Scarborough Commission (officially the "Commission of Enquiry into the Facilities for Oriental, Slavonic, East European and African Studies"[13]) report recommended a major expansion in provision for the study of Asia and the school benefited greatly from the subsequent largesse.[14] The SOAS School of Law was established in 1947 with Professor Vesey-Fitzgerald as its first head. Growth however was curtailed by following years of economic austerity, and upon Sir Cyril Philips assuming the directorship in 1956, the school was in a vulnerable state. Over his twenty-year stewardship, Phillips transformed the school, raising funds and broadening the school's remit.[14]

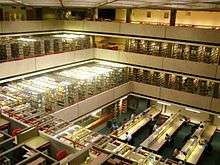

A college of the University of London, the School's fields include Law, Social Sciences, Humanities and Languages with special reference to Asia and Africa. The SOAS Library, located in the Philips Building, is the UK's national resource for materials relating to Asia and Africa and is the largest of its kind in the world.[15] The school has grown considerably over the past thirty years, from fewer than 1,000 students in the 1970s to more than 6,000 students today, nearly half of them postgraduates. SOAS is partnered with the Institut National des Langues et Civilisations Orientales (INALCO) in Paris which is often considered the French equivalent of SOAS.[16]

In 2011, the Privy Council approved changes to the school's charter allowing it to award degrees in its own name, following the trend set by fellow colleges the London School of Economics, University College London and King's College London. All new students registered from September 2013 will qualify for a SOAS, University of London, award.[17]

In 2012, a new visual identity for SOAS was launched to be used in print, digital media and around the campus. The SOAS tree symbol, first implemented in 1989, was redrawn and recoloured in gold, with the new symbol incorporating the leaves of ten trees, including the English Oak representing England; the Bodhi, Coral Bark Maple, Teak representing Asia; the Mountain Acacia, African Pear, Lasiodiscus representing Africa; and the Date Palm, Pomegranate and Ghaf representing the Middle East.[18]

Campus

The campus is located in the Bloomsbury area of central London, close to Russell Square. It includes College Buildings (the Philips Building and the Old Building), Brunei Gallery, Faber Building (23–24 Russell Square), 21–22 Russell Square and the northern Block of Senate House (since 2016). The SOAS library designed by Sir Denys Lasdun in 1973 is located in the Philips Building. The nearest Underground station is Russell Square tube station.

The school houses the Brunei Gallery, built from an endowment from the Sultan of Brunei Darussalam, and inaugurated by the Princess Royal, as Chancellor of the University of London, on 22 November 1995. Its facilities include exhibition space on three floors, a book shop, a lecture theatre, and conference and teaching facilities. The Brunei Gallery hosts a programme of changing contemporary and historical exhibitions from Asia, Africa and the Middle East with the aim to present and promote cultures from these regions.[19]

The Japanese style roof garden on top of the Brunei Gallery was built during the Japan 2001 celebrations and was opened by the sponsor, Haruhisa Handa, an Honorary Fellow of the School, on 13 November 2001.[20] The garden is dedicated to Forgiveness, which is the meaning of the kanji character engraved on the garden's granite water basin. Peter Swift, a designer with experience of adapting Japanese garden design principles to the British environment and climate, conceived the garden as a place of quiet contemplation and meditation as well as a functional space complementary to the gallery and its artistic activities.

The school hosted the Percival David Foundation of Chinese Art, one of the foremost collections of Chinese ceramics in Europe. The collection has been loaned to and is now on permanent display in Room 95 of the British Museum.

Organisation and administration

Governance

Directors

.jpg)

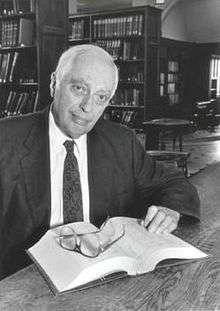

Since its foundation, the school has had nine directors. The inaugural director was the celebrated linguist Sir Edward Denison Ross. Under the stewardship of Sir Cyril Philips, the school saw considerable growth and modernisation.[21] Under Colin Bundy in the 2000s, the school became one of the top ranked universities both domestically and internationally.[22] The current Director is Valerie Amos.

| Appointed | Director |

|---|---|

| 1916 | Sir Edward Denison Ross |

| 1937 | Sir Ralph Lilley Turner |

| 1956 | Sir Cyril Philips |

| 1976 | Sir Jeremy Cowan |

| 1989 | Sir Michael McWilliam |

| 1996 | Sir Tim Lankester |

| 2001 | Colin Bundy[23] |

| 2006 | Paul Webley[24] |

| 2015 | Baroness Valerie Amos |

Faculties and departments

SOAS, University of London is divided into three faculties.[25] These are further divided into academic departments. SOAS has many Centres and Institutes, each of which is affiliated to a particular faculty.

Faculty of Arts and Humanities

The Faculty of Arts and Humanities houses the departments of Anthropology & Sociology, History of Art & Archaeology, History, Music, Philosophy and Religious Studies and the Centre for Media Studies. It offers courses at the undergraduate and post-graduate level, with an emphasis on Asia, Africa, and the Middle East. A gift from the Alphawood Foundation in 2013 created the Hiram W. Woodward Chair in Southeast Asian art, the David Snellgrove Senior Lectureship in Tibetan and Buddhist art, and a Senior Lectureship in Curating and Museology of Asian Art, as well as a number of scholarships for students, making the Department of Art & Archaeology a key institution at a global level in the study of Southeast Asia.[26]

Faculty of Languages and Cultures

Department of Linguistics

The SOAS Department of Linguistics was the first ever linguistics department in the United Kingdom, founded in 1932 as a centre for research and study in Oriental and African languages.[27] J. R. Firth, known internationally for his work in phonology and semantics, was Senior Lecturer, Reader and Professor of General Linguistics at the school between 1938 and 1956.

Faculty of Law and Social Sciences

SOAS School of Law

One of the largest individual departments, the SOAS School of Law is one of Britain's leading law schools and the sole law school in the world focusing on the study of Asian, African and Middle Eastern legal systems.[28] The School of Law has over 400 students. It offers programmes at the LL.B., LL.M. and MPhil/PhD levels. International students have been a majority at all levels for many years.

The SOAS School of Law has an unrivaled concentration of expertise in the laws of Asian and African countries, human rights, transnational commercial law, environmental law, and comparative law. The SOAS School of Law was ranked 15th out of all 98 British law schools by The Guardian League Table in 2016.[29]

Although many modules at SOAS embody a substantial element of English common law, all modules are taught (as much as possible) in a comparative or international manner with an emphasis on the way in which law functions in society. Thus, law studies at SOAS are broad and comparative in their orientation. All students study a significant amount of non-English law, start in the first year of the LL.B. course, where 'Legal Systems of Asia and Africa' is compulsory. Specialised modules in the laws and legal systems of particular countries and regions are also encouraged, and faculty experts conduct modules in these subjects every year.

Academic profile

SOAS is a centre for the study of subjects concerned with Asia, Africa and the Middle East."[30] It trains government officials on secondment from around the world in Asian, African and Middle Eastern languages and area studies, particularly in Arabic & Islamic Studies – which combined with Hebrew formed the major bulk of classical Oriental Studies in Europe – and Mandarin Chinese. It also acts as a consultant to government departments and to companies such as Accenture and Deloitte – when they seek to gain specialist knowledge of the matters concerning Asia, Africa and the Middle East.

The school is made up of nineteen departments across three faculties: Arts and Humanities, Languages and Cultures, and Law and Social Sciences. The school focuses on small group teaching with a student-staff ratio of 11:1, one of the best in the UK.[30]

Library

The SOAS library is a library for Asian, African and Middle Eastern studies.[31] It houses more than 1.2 million volumes and electronic resources for the study of Africa, Asia and the Middle East,[31] and attracts scholars from all over the world. The library is also one of the UK's five National Research Libraries.[32]

The library is housed in the Philips Building on the Russell Square campus and was built in 1973.[33] It was designed by architect Sir Denys Lasdun who also designed some of Britain's most famous brutalist buildings such as the National Theatre and the Institute of Education.

In 2010/11 the library underwent a £12 million modernisation programme, known as "the Library Transformation Project".[34] The work refurbished the ground floor of the library and created new reception and entrance areas, new music practice rooms, group study rooms and a gallery exhibition space.[35]

As a constituent college of the University of London, students at SOAS also have access to Senate House Library, shared by other colleges such as London School of Economics and University College London, which is located just a short walk from the Russell Square campus.

The library was used as a filming location for some scenes in the 2016 film Criminal.[36]

Rankings

| QS[37] (2016/17, national) | 35 | |

|---|---|---|

| QS[38] (2016/17, world) | 252 | |

| THE[39] (2016/17, national) | 57 | |

| THE[40] (2016/17, world) | 401-500 | |

| Complete[41] (2017, national) |

43 | |

| The Guardian[42] (2017, national) |

30 | |

| Times/Sunday Times[43] (2017, national) |

35 | |

The 2016 QS World University Rankings places SOAS 46th in the world for Arts & Humanities and 11th globally for Development Studies.[44]

SOAS's Department of Financial and Management Studies (DeFiMS) is ranked in the top-ten for Business Studies in the 2013 Complete University Guide's League Table. The research strength of the department has been previously recognised by the 2008 Research Assessment Exercise (RAE) where 90 per cent was rated as internationally recognised, internationally excellent or world leading quality.[45]

The results of the 2008 United Kingdom RAE took the form of profiles spread across four grade levels. Hence, there are different ways to present them and to rank the departments. In their published tables, the Times Higher and the Guardian Education chose to use an average of the profile or GPA (Grade Point Average); both rankings placed the SOAS Department of Anthropology equal second, ranking just behind Cambridge with LSE. According to the 2008 United Kingdom Research Assessment Exercise, SOAS is the national leader in the study of Asia.[46]

Student life

In 2014/15, there were 3,015 students[2] In 2012, 41% of students were over 21 and 60% were female.[47] According to the QS World University Rankings, SOAS also has the 9th highest percentage of international students in the world at 43%, who come from 140 countries.[48]

SOAS is renowned for its political scene and radical politics, and was voted the most politically active university in the UK in the Which?University 2012. Recent campaigns include students for social change, women's liberty and justice for cleaners.[49]

Located in the heart of Bloomsbury, students are minutes from the British Museum, British Library, University of London Union and the nightlife of the West End. Many University of London schools and institutes are close by, including Birkbeck, the Institute of Education, London Business School, the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine, the Royal Veterinary College, the School of Advanced Study, Senate House Library and University College London.

Student housing

SOAS operates two halls of residence in central London, both owned by Shaftesbury Student Housing.[50] The primary accommodation for undergraduates is Dinwiddy House which is located on the Pentonville Road. This contains 510 single en-suite rooms arranged in small cluster flats of around six rooms each. The halls are located within minutes of King's Cross St. Pancras tube station and the Vernon Square campus.[51]

A few minutes walk from Dinwiddy House and also on the Pentonville Road is Paul Robeson House, the second halls of residence. This was opened in 1998, and is named after the African American musician Paul Robeson who studied at SOAS. This accommodation is occupied by postgraduate students, and those attending the international SOAS Summer schools.[52]

SOAS students are eligible to apply for places in the University of London intercollegiate halls of residence.[53] The majority of these are based in Bloomsbury such as Canterbury Hall, Commonwealth Hall, College Hall, Connaught Hall, Hughes Parry Hall and International Hall, whilst further afield are Nutford House in Marble Arch and Lillian Penson Hall in Paddington.

Notable people

Notable alumni

SOAS alumni have made significant contributions in the fields of government, academia, business, arts, journalism, among others. These include Sultan Salahuddin, King of Malaysia (1999–2001), Mette-Marit, Crown Princess of Norway, Princess Ayşe Gülnev Sultan, descendant of Mehmed V Reşâd, 35th Sultan of the Ottoman Empire, John Atta Mills, Former President of Ghana, Luisa Diogo, Former Prime Minister of Mozambique, Bülent Ecevit, Former Prime Minister of Turkey.

In British politics, several current and former Members of Parliament are alumni; David Lammy, Catherine West, Tim Yeo, Ivor Stanbrook, Sir Ray Whitney, Enoch Powell. Outside the UK, political alumni include Aung San Suu Kyi, Nobel Peace Prize laureate and Member of the Burmese Parliament, Zairil Khir Johari, Member of the Malaysian Parliament,[54] Amal Pepple, Minister of Lands, Housing and Urban Development in Nigeria, Aaron Mike Oquaye, Minister of Communication in Ghana, Hüseyin Çelik, Turkish Minister of Education, Femi Fani Kayode, former Nigerian Minister of Culture and Tourism and former Minister of Aviation, Kraisak Choonhavan, Former Senator in Thailand, Samia Nkrumah, Ghanaian Member of Parliament and Mohamed Jameel Ahmed, 4th Vice President of the Maldives.

In justice, Idris Kutigi, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Nigeria, Sylvester Umaru Onu, Judge of the Supreme Court of Nigeria, Herbert Chitepo, first Black Rhodesian Barrister, John Vinelott, lawyer and judge.

Alumni with diplomatic roles include Johnnie Carson, former US Ambassador to Kenya, Zimbabwe and Uganda, Hassan Taqizadeh, Iranian Ambassador to the UK, Sir Shridath Ramphal, Secretary-General of the Commonwealth, Sir Leslie Fielding, British diplomat and former European Commission Ambassador to Tokyo, David Warren, UK Ambassador to Japan, Quinton Quayle, UK Ambassador to Thailand and Lao, Sir Robin McLaren, UK Ambassador to China and the Philippines,[55] Sir Michael Weir, UK Ambassador to Egypt, Jemima Khan, UK Ambassador to UNICEF, Hugh Carless, UK Ambassador to Venezuela,[56] Francis K. Butagira, Ambassador and Permanent Representative, Mission of the Republic of Uganda to the United Nations, Gunapala Malalasekera, Sri Lankan Ambassador to UK, Canada and Soviet Union, Michael C Williams, UN Special Coordinator for Lebanon.

.jpg)

Prominent journalists and broadcasters such as, Abdel Bari Atwan, editor-in-chief of Al-Quds Al-Arabi newspaper in London, Zeinab Badawi, presenter of BBC World News Today, Martin Bright, political editor of the Jewish Chronicle, Jung Chang, who is best known for her family autobiography Wild Swans, Hossein Derakhshan, Iranian blogger credited with starting the blogging revolution in Iran,[57] Jamal Elshayyal, news producer at Al Jazeera English, Ghida Fakhry, news anchor at Al Jazeera English, James Harding, former editor of The Times, Lindsey Hilsum, Channel 4 News correspondent and columnist for the New Statesman, Dom Joly, television comedian and journalist, Elan Journo, Fellow and Director of Policy Research at the Ayn Rand Institute, Clive King, author of Stig of the Dump, Freya Stark, travel writer and Rupert Wingfield-Hayes, BBC's Tokyo correspondent.

In academia, SOAS alumni include, Simon Digby, oriental scholar, Wang Gungwu, Australian historian of Asia, Sir Martin Harris, educationalist, Gregory B. Lee, sinologist, Bernard Lewis, Orientalist, Duncan McCargo, political scientist, Robert L. McKenzie, scholar-cum-public commentator on forced migration and refugees, Than Tun, historian of Burma, Ivan van Sertima, historian and anthropologist, William Montgomery Watt, Islamic scholar and Syed Muhammad Naquib al-Attas, a contemporary Muslim philosopher.

Noted writers include M. K. Asante author of Buck, filmmaker and professor, Raman Mundair, British poet and playwright. Olu Oguibe, a conceptual artist and academic, Derwin Panda, an electronic musician and producer, Paul Robeson, an American singer who was involved in the Civil Rights Movement, Himanshu Suri aka 'Heems', rapper and member of Das Racist and Dzongsar Jamyang Khyentse Rinpoche, a Bhutanese lama and filmmaker are all alumni of the school.

In business, alumni include: Fred Eychaner, American businessman and philanthropist,[58] Abdulsalam Haykal, Syrian media entrepreneur, Sir Peter Parker, chairman of the British Railways Board, Atiur Rahman, Governor of Bangladesh Bank and Sir Dermot de Trafford, British banker and baronet.

Notable faculty and staff

References

- ↑ "2014/15 Annual Review and Financial Statements" (PDF). SOAS. 2015. p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 "2014/15 Students by HE provider, level, mode and domicile" (XLSX). Higher Education Statistics Agency. Retrieved 19 January 2016.

- ↑ "SOAS Standing Orders: Charter and Articles". Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ↑ "guardian.co.uk | Education". London: Browse.guardian.co.uk. 17 January 2008. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ↑ "University League Table 2013". The Complete University Guide. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ↑ "Early years (1917-36)". SOAS, University of London. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 Brown, Ian. The School of Oriental and African Studies: Imperial Training and the Expansion of Learning. Cambridge University Press, 2016. ISBN 9781107164420.

- ↑ Nature, 1917, Vol.99(2470), pp. 8–9 [Peer Reviewed Journal]

- ↑ University of London: An Illustrated History: 1836–1986 By N. B. p.255

- ↑ Nature, 1939, Vol.144(3659), pp. 1006–1007

- ↑ Sadao Ōba The 'Japanese' war: London University's WWII secret teaching programme p.11

- ↑ Nisei linguists: Japanese Americans in the Military Intelligence Service ... Page 160-161

- ↑ "Commission of Enquiry into the Facilities for Oriental, Slavonic, East European and African Studies". aim25.ac.uk. 1945. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- 1 2 Professor Sir Cyril Philips – Obituaries – News. The Independent (2006-01-19). Retrieved on 2013-07-17.

- ↑ "What's it like at SOAS". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 December 2005.

- ↑ http://www.ambafrance-uk.org/IMG/pdf_100917_EC_Brochure_115x170_pdf_SG.pdf

- ↑ SOAS, University of London an Institutional Review by the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education. Qaa.ac.uk. Retrieved on 2016-05-23.

- ↑ SOAS Visual Identity FAQs, SOAS, University of London. Soas.ac.uk (2012-10-12). Retrieved on 2013-07-17.

- ↑ The Brunei Gallery, SOAS. Culture24. Retrieved on 2016-05-23.

- ↑ SOAS Japanese-Inspired Roof Garden. Opensqaures.org. Retrieved on 2016-05-23.

- ↑ "Professor Sir Cyril Philips". The Independent. London. 19 January 2006.

- ↑ "Oxford topples Cambridge from top spot". TheGuardian.co.uk. 19 April 2005. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ MacLeod, Donald (21 April 2005). "Soas head resigns after five years". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ MacLeod, Donald (7 February 2006). "Soas appoints new director". London: The Guardian. Retrieved 14 July 2012.

- ↑ "Academic Departments, Institutes, Centres and Faculties at SOAS, University of London". Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ↑ "Alphawood Foundation announced a $32 million gift to SOAS". Alphawood Foundation Chicago. Retrieved 2016-02-26.

- ↑ "Collaboration for language preservation and revitalisation in Asia". AsianCorrespondent. 14 May 2014. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings by Subject 2016 - Law". 17 March 2016.

- ↑ "University guide 2016: league table for law".

- 1 2 "SOAS, University of London (The School of Oriental and African Studies)". TheCompleteUniversityGuide. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- 1 2 "COPAC profile on SOAS Library". COPAC. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "Prospects profile on SOAS Library". Prospects.ac.uk. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "New Library (1973-1985)". SOAS, University of London. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ↑ "SOAS Library Transformation Project". John McAslan + Partners. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "Library Transformation Enters New Phase". SOAS, University of London. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- ↑ "'Criminal': Review". screendaily.com. Retrieved 2016-04-10.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings 2016/17 - United Kingdom". Quacquarelli Symonds Ltd. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings 2016/17". Quacquarelli Symonds Ltd. Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ↑ "World University Rankings 2016-17 - United Kingdom". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ↑ "World University Rankings 2016-17". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 21 September 2016.

- ↑ "University League Table 2017". The Complete University Guide. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- ↑ "University league tables 2017". The Guardian. 23 May 2013. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "The Times and Sunday Times University Good University Guide 2017". Times Newspapers. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings: SOAS, University of London". QS Top Universities. 7 December 2015.

- ↑ "RAE Profiles: SOAS". Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "RAE 2008 quality profiles: Asian Studies". Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London (S09) – Which? University". University.which.co.uk. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ "QS World University Rankings". topuniversities.co.uk. Retrieved 23 May 2016.

- ↑ "Top political unis... as voted by students – Which? University". University.which.co.uk. 10 September 2012. Retrieved 8 December 2012.

- ↑ "Sanctuary Management Services London – Information for SOAS Students". Smsstudent.co.uk. 8 September 2010. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "Sanctuary Management Services London – Dinwiddy House". Smsstudent.co.uk. 1 July 2007. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "Sanctuary Management Services London – Paul Robeson House for SOAS Students". Smsstudent.co.uk. 1 July 2007. Retrieved 16 April 2012.

- ↑ "University of London – Intercollegiate Halls". Lon.ac.uk. 26 March 2010. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ↑ "Official Portal of The Parliament of Malaysia – Representatives Members". Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- ↑ Sir Robin McLaren. Telegraph. Retrieved on 2013-07-17.

- ↑ Hugh Carless. Telegraph (2011-12-21). Retrieved on 2013-07-17.

- ↑ Jane Perrone (18 December 2003). "Weblog heaven | Media | guardian.co.uk". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 29 April 2010.

- ↑ "SOAS given £20m donation from Alphawood foundation". BBC News. 2 November 2013.

Further reading

- Arnold, David; Shackle, Christopher, eds. (2003). SOAS since the sixties. London: SOAS, University of London. ISBN 0728603535.

- Brown, Ian, ed. (2016). The School of Oriental and African Studies: Imperial Training and the Expansion of Learning. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9781107164420.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to School of Oriental and African Studies. |

- Official website

- Game, John 'The origins of SOAS as a colonial institution, training district'

- SOAS Student Union website

- SOAS graduates list

Coordinates: 51°31′19″N 0°07′44″W / 51.52205°N 0.12900°W