Sasanian civil war of 589-591

| Sasanian civil war of 589-591 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Medieval Iranian art illustrating Khosrow II and Bahram Chobin in a battle | ||||||||||

| ||||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||||

| Supporters of Bahram Chobin | Sasanian Empire |

Dissatisfied Sasanian nobles Allies: Byzantine Empire (590–591) | ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||||

|

Bahram Chobin † Zatsparham † Bryzacius Bahram Siavoshan † Zoarab (590-591) Zadespras (590–591) † |

Hormizd IV † Azen Gushnasp † Sarames the Elder † Pherochanes † Zadespras (590) Zoarab (589-590) Sarames the Younger (589-590) |

Khosrow II Vistahm Vinduyih Mahbodh Sarames the Younger (590-591) Mushegh II Mamikonian Maurice Comentiolus John Mystacon Narses | ||||||||

The Sasanian civil war of 589-591 was a conflict that broke out in 589, due to the great deal of dissatisfaction among the nobles towards the rule of Hormizd IV. The civil war lasted until 591, ending with the overthrow of the Mihranid usurper Bahram Chobin and the restoration of the Sasanian family as the rulers of Iran.

The reason for the civil war was due to king Hormizd IV's hard treatment towards the nobility and clergy, whom he distrusted. This eventually made Bahram Chobin start a major rebellion, while the two Ispahbudhan brothers Vistahm and Vinduyih made a palace coup against him, resulting in the blinding and eventually death of Hormizd IV. His son, Khosrow II, was thereafter crowned as king.

However, this did not change the mind of Bahram Chobin, who wanted to restore Parthian rule in Iran. Khosrow II was eventually forced to flee to Byzantine territory, where he made an alliance with the Byzantine emperor Maurice against Bahram Chobin. In 591, Khosrow II and his Byzantine allies invaded Bahram Chobin's territories in Mesopotamia, where they successfully managed to defeat him, while Khosrow II regained the throne. Bahram Chobin thereafter fled to the territory of the Turks in Transoxiana, but was not long afterwards assassinated or executed at the instigation of Khosrow II.

Background

When Khosrow I ascended the Sasanian throne in 531, he began a series of reforms that was started by his father and predecessor Kavadh I. These reforms were mostly aimed at the elites of the Sasanian Empire, who had become too powerful and had been able to depose several Sasanian rulers. Khosrow I was quite successful in these reforms, and after his death in 579, he was succeeded by his son Hormizd IV, who continued his father's policies, but in a harsher way; in order to control the elites, he, in the words of Shapur Shahbazi, "resorted to harshness, denigration, and execution."[1] Hormizd IV was extremely hostile to the elites and did not trust them, therefore, he constantly sided with the lower classes.

Hormizd IV also declined the requests of the Zoroastrian priesthood to persecute the Christians, and like the elites, Hormizd IV did not like the Zoroastrian priesthood either, and therefore killed a great deal of them, including the chief priest (mowbed) himself. Furthermore, Hormizd IV also greatly reduced the payment of the military by 10 percent,[2] and massacred many powerful and prominent members of elite, which included the famous Karenid vizier of his father, Bozorgmehr,[3] including the latter's brother Simah-i Burzin; the Mihranid Izadgushasp; the spahbed ("army chief") Bahram-i Mah Adhar, and the Ispahbudhan Shapur, who was the father of Vistahm and Vinduyih. According to the medieval Persian historian al-Tabari, Hormizd is said to have ordered the death of 13,600 nobles and religious members.[4]

Outbreak of the civil war

The rebellion of Bahram Chobin

In 588, a massive Hephthalite-Turkic army invaded the Sasanian province Harev. Bahram Chobin, a military genius from the House of Mihran, was appointed as the spahbed of the kust of Khorasan. He was thereafter appointed as the head of an army of 12,000 soldiers. He then made a counter-attack against the Turks, and successfully defeated them, killing their ruler Bagha Qaghan (known as Shawa/Sava/Saba in Sasanian sources).[2] After some time, Bahram was defeated by the Byzantine Empire in a battle on the banks of the Aras River. Hormizd IV, who was jealous of Bahram Chobin, used this defeat as an excuse to dismiss Bahram Chobin from his office, and had him humiliated.[5][2]

The coup in Ctesiphon and the march of Bahram Chobin

.jpg)

Bahram Chobin, furious of Hormizd actions, responded by rebelling, and due to his noble status and great military knowledge, was joined by his soldiers and many others. He then appointed a new governor for Khorasan, and afterwards set for Ctesiphon, the capital of the Sasanian Empire. Meanwhile, Hormizd tried to come to terms with Vistahm and Vinduyih, "who equally hated Hormozd".[2] Hormizd shortly had Vinduyih imprisoned, while Vistahm managed to flee from the court. After a short period of time, a palace coup under the two brothers occur in Ctesiphon, which resulted in the blinding of Hormizd and the accession of the latter's son Khosrow II (who was their nephew through his mother's side). The two brothers shortly had Hormizd killed.

A few days later, Bahram reached the Nahrawan Canal near Ctesiphon, where he fought Khosrow's men, who were heavily outnumbered, but managed to hold Bahram's men back in several clashes. However, Khosrow's men eventually began losing their morale, and were in the end defeated by Bahram Chobin's forces. Khosrow, together with his two uncles, his wives, and a retinue of 30 nobles, thereafter fled to Byzantine territory, while Ctesiphon fell to Bahram Chobin.[6]

Khosrow's flight to Byzantium and restoration

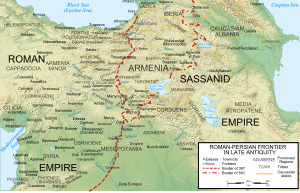

In order to get the attention of the Byzantine emperor Maurice (r. 582–602), Khosrow II went to Syria, and sent a message to the Sasanian occupied city of Martyropolis to stop their resistance against the Byzantines, but with no avail.[7] He then sent a message to Maurice, and requested his help to regain the Sasanian throne, which the Byzantine emperor agreed with; in return, the Byzantines would re-gain sovereignty over the cities of Amida, Carrhae, Dara and Miyafariqin. Furthermore, Persia was required to stop intervening in the affairs of Iberia and Armenia, effectively ceding control of Lazistan to the Byzantines.[8]

In 591, Khosrow moved to Constantia, and prepared to invade Bahram Chobin's territories in Mesopotamia, while Vistahm and Vinduyih were raising an army in Azerbaijan under the observation of the Byzantine commander John Mystacon, who was also raising an army in Armenia. After some time, Khosrow along with the Byzantine commander of the south, Comentiolus, invaded Mesopotamia. During this invasion, Nisibis and Martyropolis quickly defected to them,[9] and Bahram's commander Zatsparham was defeated and killed.[10] One of Bahram's other commanders, Bryzacius, was captured in Mosil and had his nose and ears cut off, and was thereafter sent to Khosrow, where he was killed.[11][12]

Some time later, Khosrow, feeling disrespected by Comentiolus, convinced Maurice to replace the latter with Narses as the commander of the south.[9][10] Khosrow and Narses then penetrated deeper into Bahram's territory, seizing Dara and then Mardin on February, where Khosrow was re-proclaimed king.[10] Shortly after this, Khosrow sent one of his Iranian supporters, Mahbodh, to capture Ctesiphon, which he managed to accomplish.[13]

Meanwhile, Khosrow's two uncles and John Mystacon, conquered northern Azerbaijan, and went further south in the region, where they defeated Bahram at Blarathon, who fled to the Turks of Ferghana.[14] However, Khosrow managed to deal with him by either having him assassinated[14] or convince the Turks to execute him.[14]

Aftermath

Peace with the Byzantines was then officially made. Maurice, for his aid, received much of Persian Armenia and western Georgia, and received the abolition of tribute which had formerly been paid to the Sasanians.[9] This marked the beginning of a peaceful period between the two empires, which lasted until 602, when Khosrow decided to declare war against the Byzantines after the murder of Maurice by the usurper Phocas.[15][16]

References

- ↑ Shapur Shahbazi 2004, pp. 466-467.

- 1 2 3 4 Shapur Shahbazi 1988, pp. 514-522.

- ↑ Khaleghi Motlagh, Djalal (1990). "BOZORGMEHR-E BOḴTAGĀN". Encyclopaedia Iranica. Vol. 4.

- ↑ Pourshariati 2008, p. 118.

- ↑ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, p. 167.

- ↑ James Howard-Johnston.

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 172.

- ↑ Dinavari, al-Akhbar al-tiwal, pp. 91-92

- 1 2 3 Howard-Johnston 2010.

- 1 2 3 Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 173.

- ↑ Martindale, Jones & Morris 1992, p. 251.

- ↑ Rawlinson 2004, p. 509.

- ↑ Greatrex & Lieu 2002, p. 174.

- 1 2 3 Crawford 2013, p. 28.

- ↑ Oman 1893, p. 155.

- ↑ Foss 1975, p. 722.

Sources

- Greatrex, Geoffrey; Lieu, Samuel N. C. (2002). The Roman Eastern Frontier and the Persian Wars (Part II, 363–630 AD). New York, New York and London, United Kingdom: Routledge (Taylor & Francis). ISBN 0-415-14687-9.

- Martindale, John Robert; Jones, Arnold Hugh Martin; Morris, J., eds. (1992). The Prosopography of the Later Roman Empire, Volume III: A.D. 527–641. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20160-5.

- Shahbazi, A. Sh. (1988). "BAHRĀM (2)". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. III, Fasc. 5. pp. 514–522.

- Pourshariati, Parvaneh (2008). Decline and Fall of the Sasanian Empire: The Sasanian-Parthian Confederacy and the Arab Conquest of Iran. London and New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84511-645-3.

- Shapur Shahbazi, A. (2005). "SASANIAN DYNASTY". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition. Retrieved 24 August 2014.

- Shapur Shahbazi, A. (2004). "HORMOZD IV". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. XII, Fasc. 5. pp. 466–467.

- Shapur Shahbazi, A. (1989). "BESṬĀM O BENDŌY". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Vol. IV, Fasc. 2. pp. 180–182. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- Howard-Johnston, James (2010). "ḴOSROW II". Encyclopaedia Iranica, Online Edition. Retrieved 27 February 2016.

- Crawford, Peter (2013). The War of the Three Gods: Romans, Persians and the Rise of Islam. Pen and Sword. ISBN 9781848846128.

- Rawlinson, George (2004). The Seven Great Monarchies of the Ancient Eastern World. Gorgias Press LLC. ISBN 9781593331719.

- Foss, Clive (1975). The Persians in Asia Minor and the End of Antiquity. The English Historical Review. 90. Oxford University Press. pp. 721–47. doi:10.1093/ehr/XC.CCCLVII.721.

- Oman, Charles (1893). Europe, 476-918, Volume 1. Macmillan.

- Potts, Daniel T. (2014). Nomadism in Iran: From Antiquity to the Modern Era. London and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 1–558. ISBN 9780199330799.