San Sebastián

| San Sebastián Donostia (Basque) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Donostia / San Sebastián | |||

|

San Sebastián as seen from the air | |||

| |||

|

Motto: Ganadas por fidelidad, nobleza y lealtad (Spanish for "Earnt by fidelity, nobility and loyalty") | |||

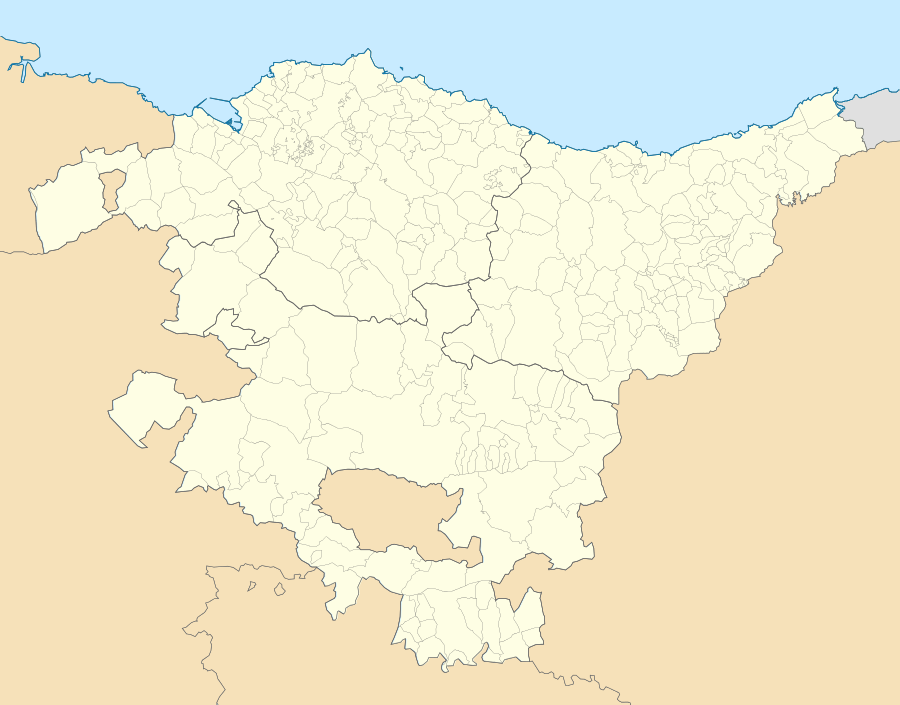

San Sebastián Location of San Sebastián within the Basque Autonomous Community | |||

| Coordinates: 43°19′17″N 1°59′8″W / 43.32139°N 1.98556°WCoordinates: 43°19′17″N 1°59′8″W / 43.32139°N 1.98556°W | |||

| Country |

| ||

| Autonomous community |

| ||

| Province | Gipuzkoa | ||

| Comarca | Donostialdea | ||

| Neighbourhoods | 21 | ||

| Founded | 1180 | ||

| Government | |||

| • Mayor | Eneko Goia Laso[1] (EAJ-PNV) | ||

| Area | |||

| • Land | 60.89 km2 (23.51 sq mi) | ||

| Elevation | 6 m (20 ft) | ||

| Population (2015) | |||

| • Total | 186,095 | ||

| • Density | 3,686.16/km2 (9,547.1/sq mi) | ||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||

| Postal codes | 20001–20018 | ||

| Area code(s) | 34 + 943 (Gipuzkoa) | ||

| Website | City Council | ||

San Sebastián (Spanish: [san seβasˈtjan], French: Saint-Sébastien) or Donostia (Basque: [doˈnos̺tia])[2] is a coastal city and municipality located in the Basque Autonomous Community, Spain. It lies on the coast of the Bay of Biscay, 20 km (12 miles) from the French border. The capital city of Gipuzkoa, the municipality's population is 186,095 (2015),[3] with its metropolitan area reaching 436,500 (2010).[4] Locals call themselves donostiarra (singular), both in Spanish[5] and Basque.

The main economic activities are commerce and tourism, and it is one of the most famous tourist destinations in Spain.[6] Despite the city’s small size, events such as the San Sebastián International Film Festival have given it an international dimension. San Sebastián, along with Wrocław, Poland, is the European Capital of Culture in 2016.[7]

Etymology

In spite of appearances, both the Basque form Donostia and the Spanish form San Sebastián have the same meaning of Saint Sebastian. The dona/done/doni element in Basque place-names signifies "saint" and is derived from Latin domine; the second part of Donostia contains a shortened form of the saint's name.[8] There are two hypothesis regarding the evolution of the Basque name: one says it was *Done Sebastiáne > Donasa(b)astiai > Donasastia > Donastia > Donostia,[9] the other one says it was *Done Sebastiane > *Done Sebastiae > *Done Sebastie > *Donesebastia > *Donasastia > *Donastia > Donostia.[10]

Geography

The city is in the north of the Basque Country, on the southern coast of the Bay of Biscay. San Sebastián's picturesque shoreline makes it a popular beach resort. The seaside environment is enhanced by hilly surroundings that are easily accessible, i.e., Urgull (at the heart of the city by the seashore), romantic Mount Ulia extending east to Pasaia, Mount Adarra rising proud far on the south and Igeldo, overlooking the bay from the west.

The city sits at the mouth of the River Urumea, Donostia having been built to a large extent over the river's wetlands during the last two centuries. In fact, the city centre and the districts of Amara Berri and Riberas de Loiola lie on such terrain and the former bed of the river, diverted to its current canalized course in the first half of the 20th century.[11]

Parts of the city

As a result of Donostia's sprawling in all directions, first into the flatlands shaped by the river Urumea and later up the hills, new districts arose after the walls of the city were demolished in 1863. The first expansion of the old town stretched out to the river's mouth, on the old quarter called Zurriola (a name later given by Council decision to the sand area and the avenue across the river).[11]:13, 322

The orthogonal layout nowadays making up the city centre (the Cortazar development) was built up to 1914 (first phase finished) much in tune with a Parisian Haussmannian style. The arcades of the Buen Pastor square were fashioned after the ones of the Rue de Rivoli, with the Maria Cristina Bridge being inspired by the Pont Alexandre III that spans the Seine.[11]:257 The Estación del Norte train station standing right across the bridge was inaugurated in 1864 just after the arrival of the railway to San Sebastián, with its metallic roof being designed by Gustave Eiffel.

Parte Vieja

The Parte Vieja (Old Town) is the traditional core area of the city, and was surrounded by walls up to 1863, when they were demolished so as to occupy the stretch of sand and land that connected the town to the mainland (a stretch of the walls still limits the Old Part on its exit to the port through the Portaletas gate). The Old Town is divided in two parishes relating to the Santa Maria and San Vicente churches, the inhabitants belonging to the former being dubbed traditionally joxemaritarrak, while those attached to the latter are referred to as koxkeroak. Historically, the koxkeroak up to the early 18th century were largely Gascon speaking inhabitants. Especially after the end of Franco's dictatorship, scores of bars sprang up all over the Old Part which are very popular with the youth and the tourists, although not as much with the local residents. Most current buildings trace back to the 19th century, erected thanks to the concerted effort and determination of the town dwellers after the 1813 destruction of the town by the allied Anglo-Portuguese troops.[12]:73–75, 81–89

There is a small fishing and recreation port, with two-floor picturesque houses lined under the front-wall of the mount Urgull. Yet these houses are relatively new, resulting from the demilitarization of the hill,[11]:218 sold to the city council by the Ministry of War in 1924.

Antiguo

This part stands at the west side of the city beyond the Miramar Palace. It is arguably the first population nucleus, even before the land at the foot of Urgull (Old Part) was settled. A monastery of San Sebastián el Antiguo ('the Old') is attested in documents at the time of the foundation (12th century).[11]:35 At the mid 19th century, industry developed (Cervezas El León, Suchard, Lizarriturry),[13] the nucleus coming to be populated by workers. Industry has since been replaced by services and the tourist sector. The Matia kalea provides the main axis for the district.

Amara Zaharra

Or Old Amara, named after the farmhouse Amara.[11]:30 It has eventually merged with the city centre to a large extent, since former Amara lay on the marshes at the left of the River Urumea. The core of this district is the Easo Plaza, with the railway terminal of Euskotren closing the square at its south.

Amara Berri

This city expansion to the south came about as of the 1940s, after the works to canalize the river were achieved.[11]:30–31, 92 Nowadays the name Amara usually applies to this sector, the newer district having overshadowed the original nucleus both in size and population. The district harbours the main road entrance to the city, with Donostia's central bus station being located between the roundabout and the river (Plaza Pio XII).[14] Facilities of many state run agencies were established here and presently Amara's buildings house many business offices. The district revolves around the axis of Avenida Sancho el Sabio and Avenida de Madrid.

Gros

The district is built on the sandy terrain across the river. The Gros or Zurriola surf beach by the river's mouth bears witness to that type of soil. In the 19th century, shanties and workshops started to dot the area, Tomas Gros being one of its main proprietors as well as providing the name for this part of the city.[11]:148–149 The area held the former monumental bullring Chofre demolished in 1973, on a site currently occupied by a housing estate. The district shows a dynamic commercial activity, recently boosted by the presence of the Kursaal Congress Centre by the beach.

Aiete

One of the newest parts in the city, it kept a rural air until not long ago.[11]:60–61 The postwar city council bought the quaint compound of the Aiete Palace for the use of Francisco Franco in 1940, right after the conclusion of the Civil War. The place in turn became the summer residence for the dictator up to 1975.[11]:62 Nowadays home to the Bakearen Etxea or Peace Memorial House.

Egia

Egia, stemming from (H)Egia (Basque for either bank/shore or hill), is a popular district of Donostia on the right side of the Urumea beyond the train station. At the beginning of the 20th century a patch of land by the railway started to be used as a football pitch, eventually turning into the official stadium of the local team Real Sociedad before it was transferred in the 1990s to Anoeta,[11]:111 south of Amara Berri (nowadays the site harbours houses). The former tobacco factory building Tabakalera, which has been converted into a Contemporary Culture Centre, conjures up the former industrial past of the area,.[11]:111 Right opposite to this building lies the Cristina Enea park, a public compound with a botanic vocation. Egia holds the city cemetery, Polloe, at the north-east fringes of the district, stretching out to South Intxaurrondo.

Intxaurrondo

This part (meaning 'walnut tree' in Basque) is a large district to the east of the city. The original nucleus lies between the railway and the Ategorrieta Avenue, where still today the farmhouse Intxaurrondo Zar, declared "National Monument", is situated since the mid-17th century. The railway cuts across the district, the southern side being the fruit of the heavy development undergone in the area during the immigration years of the 1950s and 1960s. In addition, further housing estates have been built up more recently souther beyond the N-1 E-5 E-80 E-70 ring road (South Intxaurrondo). The police force Guardia Civil runs controversial barracks there (works for new housing are underway).

Altza

Altza (Basque for alder tree) is the easternmost district of San Sebastián along with Bidebieta and Trintxerpe. It was but a quaint village comprising scattered farmhouses and a small nucleus a century ago (2,683 inhabitants in 1910), yet on the arrival of thousands of immigrants in the 1960s and 1970s a rapid and chaotic housing and building activity ensued, resulting in a maze of grey landscape of skyscrapers and 32,531 inhabitants crammed in them (data of 1970), the figure is 20,000 as of 2013.[15]

Ibaeta

Ibaeta stands on the former location for various factories (e.g., Cervezas El Leon) of San Sebastián, with the buildings of the old industrial estate being demolished in the late 20th century. The levelling of this large flat area paved the ground for a carefully planned modern and elegant housing estate, featuring a new university campus for the public University of the Basque Country (UPV-EHU)[14] and institutions such as the Donostia International Physics Center or the Nanotechnology Center. A stream called Konporta flows down along the eastern side of the area, but it was canalized under the ground almost all along to its mouth on the bay pushed by urban building pressure.

Loiola

It lies by the Urumea at the south-east end of the city. It comprises a small patch of detached houses (Ciudad Jardín) and a core area of 6-odd floor buildings. The district has recently gone through a major makeover, with works finishing in 2008. The road axis coming from important industrial areas (Astigarraga-Hernani) crosses the district heading downtown. A military base stands across the river,[16] home to an uprising in 1936. Attempts by the city council to close it have been unsuccessful so far.

Riberas de Loiola

New modern district erected in the 2000s next to the city's inner bypass and south road entrance to Donostia. A pedestrian bridge spans the Urumea river onto the Cristina Enea Park.

Martutene

The Martutene district bordering to the south on the town of Astigarraga comes next to Loiola in the south direction. This part of the city features an industrial area, a football pitch for lower leagues, a disused vocational training building and enclosure as well as a prison, much in decay and due to be transferred soon to a new location, probably in the municipality's exclave of Zubieta, while this option is coming in for much opposition.

Zubieta

The exclave Zubieta (meaning 'place of bridges') was a picturesque old village up to recent years, with a bunch of houses, a unique handball pitch (on account of its single wall as opposed to the regular two) and a church. Yet it has undergone a great urban development, which has rendered the location a built-up area with paved streets and due equipment. Two contested projects are under way to build a solid-waste incinerator and a prison nearby. Historically, neighbours from Donostia held a meeting at a house in the former village in the wake of the 1813 burning, in order to decide the reconstruction of the town.

Climate

San Sebastián features an oceanic climate with warm, but not hot summers, and cool but not cold winters. Like many cities with this climate, San Sebastián typically experiences cloudy or overcast conditions for the majority of the year, typically with some precipitation. The city averages roughly 1,650 mm (65 in) of precipitation annually, which is fairly evenly spread throughout the year. However, the city is somewhat drier and noticeably sunnier in the summer months, experiencing on average approximately 100 mm (3.94 in) of precipitation during those months. Average temperatures range from 8.9 °C (48.0 °F) in January to 21.5 °C (70.7 °F) in August.

| Climate data for San Sebastián Airport Hondarribia, (15 km (9 miles) east of San Sebastian) (1981–2010) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 24.6 (76.3) |

28.6 (83.5) |

29.0 (84.2) |

32.4 (90.3) |

36.6 (97.9) |

39.8 (103.6) |

40.4 (104.7) |

40.0 (104) |

38.0 (100.4) |

33.4 (92.1) |

29.4 (84.9) |

26.0 (78.8) |

40.4 (104.7) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 13.1 (55.6) |

13.8 (56.8) |

16.1 (61) |

17.5 (63.5) |

20.7 (69.3) |

23.1 (73.6) |

25.1 (77.2) |

25.7 (78.3) |

24.0 (75.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

16.2 (61.2) |

13.5 (56.3) |

19.2 (66.6) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 8.9 (48) |

9.4 (48.9) |

11.6 (52.9) |

13.0 (55.4) |

16.2 (61.2) |

19.0 (66.2) |

21.0 (69.8) |

21.5 (70.7) |

19.4 (66.9) |

16.4 (61.5) |

12.0 (53.6) |

9.6 (49.3) |

14.8 (58.6) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 4.7 (40.5) |

5.0 (41) |

7.0 (44.6) |

8.5 (47.3) |

11.8 (53.2) |

14.8 (58.6) |

16.9 (62.4) |

17.2 (63) |

14.7 (58.5) |

11.8 (53.2) |

7.8 (46) |

5.6 (42.1) |

10.5 (50.9) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −12.0 (10.4) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

−5.2 (22.6) |

−1.2 (29.8) |

3.0 (37.4) |

5.3 (41.5) |

7.8 (46) |

8.4 (47.1) |

4.6 (40.3) |

0.8 (33.4) |

−5.8 (21.6) |

−8.4 (16.9) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 157 (6.18) |

135 (5.31) |

124 (4.88) |

156 (6.14) |

120 (4.72) |

95 (3.74) |

85 (3.35) |

117 (4.61) |

132 (5.2) |

167 (6.57) |

188 (7.4) |

174 (6.85) |

1,649 (64.92) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1 mm) | 13 | 12 | 12 | 14 | 12 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 12 | 13 | 12 | 138 |

| Average snowy days | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 75 | 72 | 70 | 71 | 72 | 73 | 74 | 75 | 75 | 75 | 76 | 75 | 74 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 88 | 108 | 141 | 159 | 182 | 188 | 198 | 197 | 170 | 134 | 96 | 81 | 1,750 |

| Source: Agencia Estatal de Meteorología[17] | |||||||||||||

History

.jpg)

Prehistory

The first evidence of human stationary presence in the current city is the settlement of Ametzagaña, between South Intxaurrondo and Astigarraga. The unearthed remains, such as carved stone used as knives to cut animal skin, date from 24,000 to 22,000 BC. The open-air findings of the Upper Paleolithic have revealed that the settlers were hunters and Homo sapiens, besides pointing to a much colder climate at the time.[18]

Ancient Age

San Sebastián is thought to have been in the territory of the Varduli in Roman times. 10 km (6 mi) east of the current city lay the Basque Roman town of Oiasso (Irun), which was for a long time wrongly identified with San Sebastián.

Middle Age

After a long period of silence in evidence, in 1014 the monastery of St. Sebastián with its apple orchards (for cider), located in the term of Hernani, is donated to the Abbey of Leire by Sancho III of Pamplona. By 1181, the city is chartered (given fuero) by king Sancho VI of Pamplona on the site of Izurum, having jurisdiction over all the territory between the rivers Oria and Bidasoa.

In 1200, the city was conquered by Castile, whose king Alfonso VIII, confirmed its charter (fuero), but the Kingdom of Navarre was deprived of its main direct access out to the sea. Perhaps as soon as 1204 (or earlier), the city nucleus at the foot of Urgull started to be populated with Gascon-speaking colonizers from Bayonne and beyond, who left an important imprint in the city's identity in the centuries to come.[19]

In 1265, the use of the city as a seaport is granted to Navarre as part of a wedding pact. The large quantity of Gascons inhabiting the town favoured the development of trade with other European ports and Gascony. The city steered clear of the destructive War of the Bands in Gipuzkoa, the only town in doing so in that territory. In fact, the town only joined Gipuzkoa in 1459 after the war came to an end.[19] Up to the 16th century, Donostia remained mostly out of wars, but by the beginning of the 15th century, a line of walls of simple construction is attested encircling the town. The last chapter of the town in the Middle Ages was brought about by a fire that devastated Donostia in 1489. After burning to the ground, the town began a new renaissance by building up mainly on stone instead of bare timber.

Modern Age

The advent of the Modern Age brought a period of instability and war for the city. After the fall of Navarre, new state boundaries started to be drawn that left Donostia at the forefront of the Spanish border with France. New chunky and more sophisticated walls were erected and the town got involved in the wars engaged between Spain and France on the aftermath of the disappearance of the independent Kingdom of Navarre in 1521. Actually, the town provided critical naval help to the Spanish king on the frontier disputes that took place in Hondarribia, which earned the town the titles "Muy Noble y Muy Leal", recorded on its coat of arms. Moreover, the town took sides with the new emperor Charles V by sending a party to the Battle of Noain and providing help to the emperor against the Revolt of the Comuneros.

After the conquest of the Iberian Navarre and the attachment of Donostia to Gipuzkoa, Gascons, who had played a leading role in the political and economic life of the town since its foundation, began to be excluded from influential public positions by means of a string of regional sentences upheld by royal decision (regional diets of Zestoa 1527, Hondarribia 1557, Bergara 1558, Tolosa 1604 and Deba 1662).[19] Meanwhile, the climate of war and disease left the town in a poor condition that drove many fishermen and traders to take to the sea as corsairs as a way of getting a living, most of the times under the auspices of the king Philip II of Spain, who benefited from the disruption caused to and wealth obtained from the French and Dutch trade ships.

In 1656, the city was used as the royal headquarters during the marriage of the Infanta to Louis XIV at Saint-Jean-de-Luz nearby. After a relatively peaceful 17th century, the town was besieged and taken over by the troops of the French Duke of Berwick up to 1721. However, San Sebastián was not spared by shelling in the French assault and many urban structures were reconstructed, e.g. a new opening in the middle of the town, the Plaza Berria (that was to become the current Konstituzio Plaza).

In 1728, the "Real Compañía Guipuzcoana de Caracas was founded and boosted commerce with the Americas. Thanks to the profit the company generated, the town underwent some urban reforms and improvements and the new Santa Maria Church was erected by subscription. This period of wealth and development was to last up to the end of 18th century.[12]:56/58

In 1808, Napoleonic forces captured San Sebastián in the Peninsular War. In 1813, after a siege of various weeks, on 28 August, during the night, a landing party from a British Royal Navy squadron captured Santa Clara Island, in the bay. Situated on a narrow promontory that jutted out into the sea between the waters of the Bay of Biscay and the broad estuary of the Urumea River, the town was hard to get at and well fortified – "it was the strongest fortification I ever saw, Gibraltar excepted", wrote William Dent.[20] Three days later, on 31 August, British and Portuguese troops besieging San Sebastián assaulted the town. The relieving troops ransacked and burnt the city to the ground. Only the street at the foot of the hill (now called 31 August Street) remained.

Contemporary history

After the destructive events, the reconstruction of the city was decided in the same spot with an only slightly altered layout, since a modern octagonal draft project by the architect P.M. Ugartemendia was turned down and eventually M. Gogorza's blueprint was approved, while supervised and implemented by the former. This area, the Old Part, oozes neoclassical, austere and systematic style in its architectural construction. The Constitution Square was built in 1817 and the town hall (current library) between 1828 and 1832.[11]:100 Housing works were carried out gradually during various decades until they were achieved.

The liberal and bourgeois San Sebastián became capital of Gipuzkoa (at the expense of Tolosa) until 1823, when absolutists assailed the town again (only 200 inhabitants remained in town when the assaulting troops broke in), but it was made capital city again in 1854.[21] In 1833, British volunteers under Sir George de Lacy Evans defended the town against Carlist attack, and their fallen were buried at the "English Cemetery" on the hill Urgull.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the local government was still ruled on the principle of nobility, while the inhabitants of foreign origin or descent had always been ubiquitous in the town, especially the traders. Although San Sebastián benefited greatly from the charts system established in the Basque Country (foruak, with borders in the Ebro river and no duties for overseas goods), the town was at odds with the more traditional Gipuzkoa, even requesting the detachment from the province and the annexation to Navarre in 1841.

In 1863, the defensive walls of the town were demolished (their remains are visible in the underground car-park at the Boulevard) and an expansion of the town began in an attempt to escape the military function it had held before.[14] Works were appointed to Jose Goicoa and Ramon Cortazar, who modeled the new city according to an orthogonal shape much in an neoclassical Parisian style, and the former designed elegant buildings, like the Miramar Palace, or the Concha Promenade.[11]:145–146 The city was chosen by the Spanish monarchy to spend the summer following the French example of the near Biarritz. Subsequently, the Spanish nobility and the diplomatic corps opened residences in the summer capital. As the "wave baths" at La Concha conflicted with shipbuilding activity, shipyards relocated to Pasaia, a near bay formerly part of San Sebastián.

However, in 1875, war battered the town again and shelling over the city by Carlists caused acclaimed bertsolari and poet Bilintx to die in 1876.[21] As of 1885, King Alfonso XII of Spain's widow Maria Cristina spent her summer in Donostia on a yearly basis (took accommodation at the Miramar Palace), bringing along her retinue. In 1887, the Casino was erected, which eventually turned into the current city hall, and somewhat later the Regional Government's (Diputación's) building was completed in the Gipuzkoa Plaza following Jose Goicoa's design. Cultural life thrived on this period, giving rise to various typical events in the city, such as the Caldereros or the Tamborrada, and journalistic and literary productions both in Spanish and Basque.

After much debate within the city over its vocation, either tourism or manufacturing, Donostia developed into a fully-fledged seaside resort, but some industry developed in the district of Antiguo and outskirts of the city. Following the outbreak of World War I, San Sebastián became an attracting focus for renowned international figures of culture and politics,[21] e.g. Mata Hari, Leon Trotsky, Maurice Ravel, Romanones, etc.

Various rationalist architectural landmarks, typically white or light toned, were erected and dotted the urban landscape in the 20s and 30s (La Equitativa, Nautico, building Easo, etc.). In 1924-1926, works to canalize the Urumea river were carried out on the southern tip of the city. However, after the city's Belle Epoque in the European war time, repression under Miguel Primo de Rivera's dictatorship didn't favour the city. In 1924, gambling was prohibited by the authoritarian regime, causing the Grand Casino and the Kursaal (1921) to struggle to survive.

In 1930, Spanish republican forces signed up the Pact of San Sebastián leading to the Second Spanish Republic. Unrest and repression did not stop with the new political regime, and large-scale industrial action was taken several times by the growing anarchist, communist and socialist unions. The 1936 military coup was initially defeated by resistance led by the Basque Nationalists,[22]:226 anarchists and communists, but later that year the province fell to Spanish Nationalist forces during the Northern Campaign.[23]:397 The occupation proved disastrous for the city dwellers: between 1936 and 1943, 485 people were executed as a result of pseudo-trials by the Spanish Nationalists (Requetés and Falangists),[24]:431 including the mayor. Extrajudicial executions (paseos) by the rebel occupying military account for an estimate of over 600 individuals murdered in the area during the first months.[25]:431 Many children were evacuated to temporary safety in Bilbao, with the city draining on an exodus estimated at 40,000 to 50,000 inhabitants.

In the aftermath of war, the city was stricken by poverty, famine and repression, coupled with thriving smuggling. Many republican detainees were held at the Ondarreta prison in grim and humid conditions (building demolished in 1948) right at the beach with the same name. However, industry developed and paved the way for the urban expansion in the popular district Egia and eclectic styled Amara Berri, on the marshes and riverbed of the Urumea, at the end of the 1940s and beginning of the 1950s.

In 1943, the seeds of the Basque language schools were being sown by Elvira Zipitria, who started to give instruction in Basque at her own house in the Old Part. In 1947, the Grand Casino was turned into the City Hall.[11]:95 A decade later, in 1953, businessmen from the city organised the first San Sebastián International Film Festival to stimulate the economic life and national and international profile of the city.

The massive immigration from various parts of Spain, spurred by growing industrial production, greatly increased population, in turn bringing about a quick and chaotic urban development on the outskirts of the city (Altza, Intxaurrondo, Herrera, Bidebieta, etc.), but social, cultural and political contradictions and inequities followed, so sparking dissatisfaction. A general climate of protest and street demonstrations ensued, driven by Basque nationalists (especially armed separatist organisation ETA) and underground unions, triggering in 1968 the first state of emergency in Gipuzkoa. Several more were imposed by the Francoist authorities in the run-up to the dictator's death in 1975.

In the middle of the shaky economic situation and real estate speculation, the iconic buildings Kursaal and Chofre bullring in Gros were demolished in 1973.[21] On the other hand, sculptor Eduardo Chillida's and architect Luis Peña Ganchegui's landmark The Comb of the Winds was built at the bay's western tip (1975–1977). The 1970s to the mid-1980s were years of general urban and social decay marked by social and political unrest and violence.

In 1979, the first democratic municipal elections were held, won by the Basque Nationalist Party, who held office along with splinter party Eusko Alkartasuna (Basque Solidarity) until 1991. The Spanish Socialist Workers' Party's Odon Elorza took over as mayor that year until 2011, when he was overthrown unexpectedly in elections by Juan Carlos Izagirre (Bildu).[21]

As of the 1990s, a major makeover of the city centre was undertaken aimed at enhancing and revamping the neoclassical and modernist side of San Sebastián's architecture. Other milestone works include the reshape and enlargement of the Zurriola beach and promenade and the inauguration of the Kursaal Palace cubes (1999),[21] or the new university campus and technological facilities in Ibaeta, the provision of a wide bike lane network, underground car-parks and significant public transport improvements. Districts of cutting-edge design have been erected, such as Ibaeta or Riberas de Loiola, while some important projects hang on the balance prompted by financial tensions.

Culture and events

San Sebastián shows a dynamic cultural scene, where grass-roots initiative based on different parts of the city and the concerted private and public synergy have paved the ground for a rich range of possibilities and events catering to the tastes of a wide and selected public alike. The city was selected as European Capital of Culture for 2016 (shared with Wrocław, Poland) with a basic motto, "Waves of people's energy", summarizing a clear message: people and movements of citizens are the real driving force behind transformations and changes in the world.

Events ranging from traditional city festivals to music, theatre or cinema take place all year round, while they specially thrive in summer. In the last week of July, San Sebastián's Jazz Festival (Jazzaldia), the longest, continuously running Jazz Festival in Europe is held. In different spots of the city gigs are staged, sometimes with free admission. The Musical Fortnight comes next extending for at least fifteen days well into August and featuring classical music concerts. In September, the San Sebastián International Film Festival comes to the spotlight, an event with more than 50 years revolving around the venues of Kursaal and the Victoria Eugenia Theatre. The city is also home to the San Telmo Museoa, a major cultural institution with an ethnographic, artistic and civic vocation.

Sticking to the cinematic language but lacking its echo, Street Zinema is an international audiovisual festival exploring contemporary art and urban cultures. Other rising and popular events include the Horror and Fantasy Festival in October (21st edition in 2010) and the Surfilm Festibal, a cinema festival featuring surfing footage, especially shorts. During centuries, the city has been open to many influences that have left a trace, often mingling with the local customs and traditions and eventually resulting in festivals and new customs.

San Sebastián Day

Every year on 20 January (the feast of Saint Sebastian), the people of San Sebastián celebrate a festival known as the "Tamborrada". At midnight, in the Konstituzio plaza in the "Alde Zaharra/Parte Vieja" (Old Part), the mayor raises the flag of San Sebastián (see in the infobox). For 24 hours, the entire city is awash with the sound of drums. The adults, dressed as cooks and soldiers, march around the city. They march all night with their cook hats and white aprons with the March of San Sebastián.[16]

On this day a procession was held in the early 19th century from the Santa Maria Church in the Old Part to the San Sebastián Church in the district of Antiguo, while later limited on the grounds of weather conditions to the in-wall area. The event finished with a popular dancing accompanied on the military band's flutes and drums. In addition, every day a soldier parade took place to change the guards at the town's southern walls. Since the San Sebastián Day was the first festival heralding the upcoming Carnival, it's no surprise that some youths in Carnival mood followed them aping their martial manners and drumrolls, using for the purpose the buckets left at the fountains.[12]:107 In the period spanning the 1860s and 1880s the celebrations started to shape as we know them today with proper military style outfits and parades and the tunes fashioned by music composer Raimundo Sarriegui.[12]:110

Adults usually have dinner in sociedades gastronómicas ("gourmet clubs"), who traditionally admitted only males, but nowadays even the strictest ones allow women on the "Noche de la Tamborrada". They eat sophisticated meals cooked by themselves, mostly composed of seafood (traditionally elvers, now no longer served due to its exorbitant price) and drink the best wines. For "Donostiarras" this is the most celebrated festival of the year.

Semana Grande/Aste Nagusia

A festival called Semana Grande in Spanish and Aste Nagusia in Basque ("Big/Main Week") is held every year in mid-August. An important international fireworks contest takes place, in which a fireworks presentation is made every night over the bay and, at the end, the contest's winner is declared.[16] It also highlights the parade of giants and big-heads every afternoon.

Basque Week

This decades long festivity taking place at the beginning of September features events related to Basque culture, such as performances of traditional improvising poets (bertsolaris), Basque pelota games, stone lifting contests, oxen wagers, dance exhibitions or the cider tasting festival. Yet the main highlight may be the rowing boat competition, where teams from different towns of the Bay of Biscay contend for the Flag of La Concha. Thousands of supporters coming from these coastal locations pour into the city's streets and promenades overlooking the bay to follow the event, especially on the Sunday of the final race. All day long the streets of the Old Part play host to droves of youths clad in their team colours who party there in a cheerful atmosphere.

Santa Ageda Bezpera

Saint Agatha's Eve is a traditional event taking place at the beginning of February or end of January in many spots of the Basque Country. It holds a small but cherished slot in the city's run-up to the Carnival. Groups dressed up in Basque traditional farmer costume march across the neighbourhood singing and wielding a characteristic stick beaten on the ground to the rhythm of the traditional Saint Agatha's tune.[16] The singers ask for a small donation, which can be money, a drink or something to eat.

Caldereros

This is a local festival held on the first Saturday of February linked to the upcoming Carnival, where different groups of people dressed in Romani (Gypsy) tinkers attire take to the streets banging rhythmically a hammer or spoon against a pot or pan, and usually bar-hop while they sing the traditional songs for the occasion. They were just men voices some time ago, but women participate and sing currently too. The festival is 131 years old in 2015.

Santo Tomas

This popular festival takes place on the 21 December, a date frequently shrouded in winter cold. From early in the morning, stalls are arranged across the city centre and people from all Gipuzkoa flock to the streets of the centre and the Old Part, with crowds of people often dressed in traditional Basque "farmer" outfit turning out and filling the area. Traditional and typical produce is showcased and sold on the stalls, while the main drink is cider and the most popular snacks are txistorra (a type of thin, uncured chorizo) wrapped in talos (flatbread). A large pig is on display in the Konstituzio Plaza, which is raffled off during the festival.[16]

Olentzero

As in other Basque cities, towns and villages, on Christmas Eve the Olentzero and the accompanying carol singers usually dressed in Basque farmer costume take over the streets, especially in the city centre, asking for small donations in bars, shops and banks after singing their repertoire. Sometimes Olentzero choirs roam around the streets in later dates, on the 31st for example, and are often related to cultural, social or political associations and demands.

Gastronomy

Donostia is renowned for its Basque cuisine. San Sebastián and its surrounding area is home to a high concentration of restaurants boasting Michelin stars including Arzak (San Sebastián), Berasategi (Lasarte), Akelarre (district Igeldo) and Mugaritz (Errenteria), to mention but a few.[26] It is the second city with the most Michelin stars per capita in the world,[27] only behind Kyoto, Japan. Additionally, based on the 2013 ranking, two of the world's top ten best restaurants can be found here.[28] Adding to these cooking highlights, the city features tasty snacks similar to tapas called pintxos, which may be found at the bars of the Old Quarter.

It is also the birthplace of Basque gastronomical societies, with the oldest recorded mention of such a txoko back in 1870. In addition, it boasts the first institution to offer a university degree in Gastronomy, Basque Culinary Center.[29]

University

Donostia-San Sebastián has become an important University town. Four universities and a superior conservatory are present in the city:

- University of the Basque Country (UPV/EHU): San Sebastián hosts the Gipuzkoa Campus of the public university.

- University of Navarra: The private university has an engineering-centered campus, Tecnun, in San Sebastián.

- Universidad de Deusto: Built in 1956, the San Sebastián campus of the private university offers different university degrees.

- Mondragon University: The pioneering Faculty of Gastronomic Sciences of this private university is located in San Sebastián.

- Musikene: The Higher School of Music of the Basque Country is located in San Sebastián.

The secondary studies activity is having an increasing impact on social, cultural, technological and economical levels of the city and surroundings. With its pushing innovative and research centers and its research strategies it is becoming one of Spain's main Science production locations, along with Barcelona, Madrid, Bilbao, Seville and Valencia, among others. Donostia-San Sebastian's Scientific production covers areas like Materials Science, Cancer Research, Alzheimer and Parkinson, Architecture, Polymer Science, Biomaterials, Nanotechnology, Robotics or Informatics.

Sport

The principal football club in the city is Real Sociedad. After three seasons in the Segunda División, the club won promotion back to La Liga after winning the 2009–10 Segunda División.[30] Real Sociedad was one of the founding members of the top division in Spanish football, La Liga. They enjoyed a particularly successful period of history in the early 1980s when they were Spanish champions for two years running (1980–81, 1981–82). The city's Anoeta Stadium located at the Anoeta Sports Complex is home to the Real Sociedad and also hosts rugby union matches featuring Biarritz Olympique or Aviron Bayonnais.

Each summer the city plays host to a well known cycling race, the one-day Clásica de San Sebastián (San Sebastián Classic). Cycling races are extremely popular in Spain, and the Clásica de San Sebastián professional is held during early August. It has been held annually in San Sebastián since 1981. The race is part of the UCI ProTour and was previously part of its predecessor the UCI Road World Cup.

Famous people from San Sebastián

- José Luis Álvarez Enparantza "Txillardegi" (1929-2012), Basque linguist, politician and writer.

- Luis Miguel Arconada Etxarri, (born 26 June 1954) is a former Real Sociedad and Spain's team footballer, as goalkeeper.

- Mikel Arteta (1982-), professional footballer, formerly of local team Real Sociedad and Scottish Premier League team Rangers who most recently played for English Premier League club Arsenal.

- Julio Urquijo Ibarra (1871-1950), Basque linguist.

- Serafin Baroja (1840–1912), writer, Basque culture advocate and liberal. Father of Pio Baroja.

- Pio Baroja (1872–1956), writer belonging to the Generation of '98.

- Carlos Bea, (born April 18, 1934), United States federal judge for the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals

- Alvaro Bermejo[31] (born 1 August 1959) writer and journalist, author of best sellers like The Tibetan Gospel or The Labyrint of Atlantis.

- Indalezio Bizkarrondo "Bilintx" (1831–1876), a romantic poet and bertsolari closely attached to the city. Died after being hit by Carlist shelling.

- Achille Broutin (1860–1918), fencer and collector of weapons.

- Emmanuel Broutin (1826–1883), fencer.

- Eduardo Chillida (1924–2002), sculptor, notable for his monumental abstract works.

- Rafael Echagüe y Bermingham, governor of Puerto Rico and Philippines.

- Alfredo Goyeneche, president of Spanish Olympic committee.

- Alberto Iglesias (1955-), music composer.

- Jesús María de Leizaola (1896-1989), President of the Basque Government in exile after 1960.

- Sir Gilbert Mackereth (1892-1962), British World War I hero, holder of Military Cross for gallantry. Retired to live in San Sebastián and died there 1962, interred at San Sebastián

- Xabi Alonso (1981-), professional footballer born in Tolosa but raised in San Sebastián. Formerly of Real Sociedad, Liverpool and Real Madrid. Now plays for Bayern Munich. Part of the World Cup winning Spanish National Team.

- Iker Martínez de Lizarduy Lizarribar (1977-), Olympic sailor.

- Miguel Muñoa Pagadizabal (1868-1953), philanthropist.

- Julio Medem (1958-), film director.

- Mercedes Quesada Etxaide (1919-2006), mother of the former President of Mexico, Vicente Fox

- La Oreja de Van Gogh, famous pop rock band.

- Rebeca Linares (1983-), Spanish pornographic actress

- Duncan Dhu, pop rock band

- Alex Ubago (1981-), pop songwriter and singer. Born in Vitoria but raised in San Sebastián.

- Mariano Ferrer (1939-), journalist and radio broadcaster.

- Aritz Aduriz (1981-), footballer for Athletic Bilbao and winner of the 2015 Zarra Trophy as best Spanish goalscorer in La Liga.

- Ramon Lazkano (1968-), composer.

International relations

Twin towns – sister cities

San Sebastián is twinned with:

| Country | Twin | County/District/State/Region | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boujdour | Tindouf Province | |||

| Marugame |  | Kagawa | |

| Plymouth |  | Devon | ||

| Reno |  | Nevada | |

| Stepanakert | |||

| Trento |  | Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol | |

| Wiesbaden |  | Hesse |

Notes

- ↑ (Spanish)

- ↑ Donostia (Basque) / San Sebastián (Spanish), El Diario Vasco, Thursday 29 December 2011. (Spanish)

- ↑ "Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (Spanish Statistical Institute)". www.ine.es. Retrieved 2016-11-29.

- ↑ Proyecto Audes. Archived 22 August 2011 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Donostiarra. Diccionario de la Real Academia Española.

- ↑ "Geography and Economy of Donostia-San Sebastián". Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ↑ European Commission of Culture (28 June 2011). "Donostia-San Sebastián to be the European Capital of Culture in Spain in 2016". Retrieved 3 July 2011.

- ↑ Trask, L. The History of Basque Routledge: 1997 ISBN 0-415-13116-2

- ↑ (Spanish) Koldo Mitxelena: Apellidos vascos, 1955, 96. orrialdea.

- ↑ (Spanish) «Donostia-San Sebastián: Onomástica», Auñamendi Eusko Entziklopedia.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Sada, Javier Maria; Sada, Asier (2007). San Sebastián: La Historia de la Ciudad a través de sus Calles, Plazas, Barrios, Montes y Caminos (3rd ed.). Andoain: Txertoa. p. 92. ISBN 978-84-7148-399-7.

- 1 2 3 4 Sadaba, Javier; Sadaba, Javier (1995). Historia de San Sebastián. San Sebastián: Editorial Txertoa. ISBN 84-7148-318-1. Book in Spanish

- ↑ Segurola Lázaro, Carmen. "La Actividad Económica". GEOGRAFIA E HISTORIA DE DONOSTIA-SAN SEBASTIAN. Ingeba. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 Gomez Piñeiro, Javier. "La Estructura Urbana". GEOGRAFIA E HISTORIA DE DONOSTIA-SAN SEBASTIAN. Ingeba. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ↑ "Auzoak eta Herriak: Altza". Donostiako Udala - Ayuntamiento de San Sebastián. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Saez Garcia, Juan Antonio. "La Tamborrada y otras Fiestas". GEOGRAFIA E HISTORIA DE DONOSTIA-SAN SEBASTIAN. Ingeba. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ↑ "VValores climatológicos normales. Hondarribia, Malkarroa". November 2015.

- ↑ "Hallan un centenar de objetos de hace 22.000 años en el parque de Ametzagaina". El Diario Vasco. Retrieved 17 September 2011. Article in Spanish

- 1 2 3 "LOS GASCONES EN GUIPÚZCOA" (in Spanish). IMPRENTA DE LA DIPUTACION DE GUIPUZCOA. Retrieved 17 September 2011.

- ↑ L. Woodford (ed.), A Young Surgeon in Wellingtons Army: the Letters of William Dent (Old Woking, 1976), p. 39.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Berruso Barés, Pedro. "San Sebastián en los Siglos XIX y XX". GEOGRAFIA E HISTORIA DE DONOSTIA-SAN SEBASTIAN. Ingeba. Retrieved 15 August 2013.

- ↑ Hugh Thomas (2001). Spanish Civil War.

- ↑ Hugh Thomas (2001).

- ↑ Paul Preston (2013). The Spanish Holocaust: Inquisition and Extermination in Twentieth-Century Spain. London, UK: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-638695-7.

- ↑ Paul Preston (2013).

- ↑ "Donostia-San Sebastián Michelin restaurants". Via Michelin. 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ "The 20 Most Michelin-Starred Cities In The World (PHOTOS)". The Huffington Post.

- ↑ "The World's 50 Best Restaurants (1-10)". The World's 50 Best Restaurants. William Reed Business Media Ltd. 2013. Retrieved 12 August 2013.

- ↑ "Home - Basque Culinary Center". bculinary.com.

- ↑ "Real Sociedad & Levante Promoted To Primera Liga". Goal.com. 2010-06-13. Retrieved 2012-08-17.

- ↑ Álvaro Bermejo

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to San Sebastián. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for San Sebastián. |

- Official website

- Tourist information

- Biarritz Airport to San Sebastian Travel

- Official website of the candidature to European Capital of Culture 2016

- Images of San Sebastián in 1909

- San Sebastian Donostia Tourist Information

- Photos of San Sebastián

- San Sebastian Donostia Giants and big-heads

- Donostia photos

- San Sebastián - Donostia Photo Gallery

- "Donostia" group on Flickr

- DONOSTIA in the Bernardo Estornés Lasa - Auñamendi Encyclopedia (Euskomedia Fundazioa) (Spanish)

- Tourism in the Basque Country

- Biarritz Airport to San Sebastian

- University in San Sebastian

- Donostia Fairtrade Town Profile

- The stylish San Sebastian travel guide

- San Sebastian Details