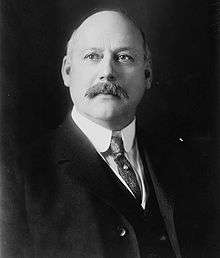

Samuel W. McCall

| Samuel Walker McCall | |

|---|---|

|

Portrait by unknown artist, published 1916 | |

| 47th Governor of Massachusetts | |

|

In office January 6, 1916 – January 2, 1919 | |

| Lieutenant | Calvin Coolidge |

| Preceded by | David I. Walsh |

| Succeeded by | Calvin Coolidge |

| Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 8th district | |

|

In office March 4, 1893 – March 3, 1913 | |

| Preceded by | Moses T. Stevens |

| Succeeded by | Frederick S. Deitrick |

| Member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives | |

|

In office 1889-1892 | |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

February 28, 1851 East Providence Township, Pennsylvania |

| Died |

November 4, 1923 (aged 72) Winchester, Massachusetts |

| Resting place | Wildwood Cemetery |

| Political party | Republican |

| Alma mater | Dartmouth College |

Samuel Walker McCall (February 28, 1851 – November 4, 1923) was a Republican lawyer, politician, and writer from Massachusetts. He was for twenty years (1893-1913) a member of the United States House of Representatives, and the 47th Governor of Massachusetts, serving three one-year terms (1916–19). He was a moderately progressive Republican who sought to counteract the influence of money in politics.

Born in Pennsylvania and educated at Dartmouth, he settled in Massachusetts, where he entered local politics on a progressive reform agenda. Elected to Congress, he continued his reform activities, and opposed annexation of The Philippines. He did not join the Progressive Party, but was insufficiently conservative for state party leaders, who denied him election to the United States Senate on two occasions. As governor, he directed the state's actions during World War I, and orchestrated early aid to Halifax, Nova Scotia following a devastating munitions ship explosion there in 1917.

Early years and education

Samuel Walker McCall was born in East Providence Township, Pennsylvania on February 28, 1851, to Henry and Mary Ann (Elliott) McCall, the sixth of eleven children.[1] At a young age, the family moved to an undeveloped frontier area of northern Illinois, where McCall spent much of his childhood.[2] McCall's father speculated in real estate and owned a stove factory, which was closed by financial reverses of the Panic of 1857.[3] His education began at the Mount Carroll Seminary (now Shimer College) in Mount Carroll from 1864 to 1866,[4] when that school closed to male students.[5]

McCall's parents then sent him east to the New Hampton Academy in New Hampton, New Hampshire, on the recommendation of a neighbor.[4] McCall graduated from New Hampton Academy in 1870 and subsequently attended Dartmouth College, where he was a member of the Kappa Kappa Kappa fraternity and graduated Phi Beta Kappa near the top of his class. While at Dartmouth, he published a newspaper (self-financed by himself and the other editors) called the Anvil, and was tapped by the Dartmouth president to stand in for a sick teacher of Latin and Greek at an academy in Meriden, New Hampshire.[6] The Anvil was one of the first student-run newspapers to comment on national and state politics.[7]

After graduating, McCall moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, where he studied law and gained admission to the Massachusetts Bar.[8] He then opened a law practice in Boston with a Dartmouth classmate,[9] which he maintained for most of his life.[8] In 1888, he and two partners purchased the Boston Daily Advertiser, for which he served as editor-in-chief for two years.[7] In 1881 he married Ella Esther Thompson, whom he met while attending New Hampton Academy;[10] they settled in Winchester, Massachusetts,[7] where they raised five children.[8]

Legislative career

McCall was elected a member of the Massachusetts House of Representatives in 1887, serving three terms in 1888, 1889, and 1892.[7] Politically a reform-minded Mugwump (he had supported Democrat Grover Cleveland in 1884), he introduced legislation to govern so-called "corrupt practices" of elected officials, intended to reduce the influence of money and favors in politics.[11][12] The legislation failed to pass the legislature until 1892.[13] He also supported legislation abolishing imprisonment for debt.[7] He was a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1888,[14] and served as the state's ballot commissioner in 1890 and 1891.[7]

In 1892, McCall was elected to the United States House of Representatives, a seat he would occupy for twenty years,[15] generally winning reelection by large margins.[7] As he had in the state legislature, he introduced a corrupt practices act into Congress. In foreign policy, he was anti-imperialist, arguing for the indepence of The Philippines after the Spanish-American War,[16] and opposed the Dingley Tariff, arguing its rates were too high. He was one of the few representatives opposed to the Hepburn Act, which enabled the Interstate Commerce Commission to regulate railroad rates.[7][17] He had a reputation as a bit of a maverick, because he often strayed from the Republican party line, but he maintained a generally conservative voting record, and introduced little new legislation.[7]

In 1912, McCall refused to stand for reelection, and was instead considered by the state legislature for election to the United States Senate in early 1913, to succeed the outgoing Senator Winthrop Murray Crane. His opponent, John W. Weeks, was more conservative Republican who had the support of most of the Crane-dominated state party apparatus. The contest was bitterly divisive, an echo of the Progressive Party split that damaged the party at the national level, and was narrowly won by Weeks,[18] even though McCall led in the party caucus balloting for the first three ballots.[7]

Governor of Massachusetts

McCall was chosen by the party in 1914 as its nominee for Governor of Massachusetts, as a unifying force between the more progressive and conservative wings of the party. Running against the popular Democratic incumbent David I. Walsh on a progressive platform, McCall was narrowly defeated,[19] with the Republican votes split due to the presence of a Progressive Party candidate on the ballot.[7] McCall was nominated again in 1915, with the Republicans deliberately courting the Progressive vote by calling for a state constitutional convention.[7] In a rematch with Walsh, he was this time victorious. He served three consecutive terms, with future President Calvin Coolidge as his lieutenant governor. In each election, Coolidge won more votes than McCall did, and the Boston Transcript credited at least one of his victories to Coolidge's drawing power.[20]

The Massachusetts Constitutional Convention of 1917–1918 was the major political event of McCall's tenure. The convention proposed a number of reforms, most of which were adopted by the voters. State commissions and agencies were streamlined, and initiative and referendum measures were added to the state constitution. Elections for statewide offices were changed from annual to biennial, beginning in 1920. Legislative reforms proposed by McCall to the state legislature were only partially adopted; proposals reforming state insurance and the public pension program were left in the legislature, and his proposal to abolish capital punishment also failed.[21]

Anticipating American entry into World War I in early 1917, McCall formed the Massachusetts Public Safety Commission,[22] an emergency response and relief organization that was the first of its type in the nation.[23] Coordinating a wide array of public and charitable organizations and major businesses, the commission played a significant role in providing relief and other services until it was disbanded in 1918.[24] One of its most important actions was coordinating the state's response to the Halifax Explosion of December 6, 1917. With only fragmentary reports received early after a blast devastated the Nova Scotia city of Halifax, McCall called the committee into action, and offered unlimited assistance to the stricken city.[23] The state organized a major relief train (even before the full extent of the disaster was known) that was among the first to reach Halifax, and the committee's representatives assisted in organizing relief activities on the ground.[25] Temporary housing built in Halifax was named in McCall's honor,[26] and the state's relief efforts continue to be recognized today by Nova Scotia's annual gift of a Christmas tree to the city of Boston.[27]

In 1918, McCall decided not to run for reelection, and again stood for the United States Senate. In a party nomination rematch with Weeks, he abandoned the campaign after it became clear the conservative Crane wing of the party was standing with Weeks. The seat ended up being won by ex-Governor Walsh in a Democratic upset.[28] In the general election, McCall refused to campaign on Weeks' behalf, a move that contributed to the end of his political career. In 1920, he was nominated by President Woodrow Wilson for a seat on the United States Tariff Commission; the nomination was rejected by the Republican-controlled Senate.[21]

Later years

McCall was engaged in literary pursuits for many years, writing in newspapers and magazines of the day. Following his exit from politics he focused on these activities, writing for the Atlantic Monthly magazine, and working on political biographies. His writings include biographies of his mentor Thomas Brackett Reed, Pennsylvania politician Thaddeus Stevens, and he was working in a biography of Daniel Webster when he died.[21]

McCall died in Winchester on November 4, 1923. His interment was in Wildwood Cemetery.[29] His grandson, Tom McCall, was a two-term Republican Governor of Oregon, serving from 1967 to 1975.[30]

Notes

- ↑ Evans, p. 2

- ↑ Evans, p. 3

- ↑ Gentile, p. 835

- 1 2 Evans, p. 7

- ↑ The History of Carroll County, Illinois. H.F. Kett & Co. 1878.

- ↑ Evans, pp. 14-16

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Gentile, p. 836

- 1 2 3 Toomey & Quinn, p. 109

- ↑ Evans, p. 18

- ↑ Evans, p. 10

- ↑ Sobel, p. 89

- ↑ Abrams, p. 270

- ↑ Evans, pp. 24, 27

- ↑ Evans, p. 23

- ↑ Evans, p. 28

- ↑ Abrams, p. 30

- ↑ Abrams, pp. 126-127

- ↑ Sobel, pp. 78-79

- ↑ Sobel, pp. 89-90

- ↑ Sobel, pp. 101, 107-109

- 1 2 3 Gentile, p. 837

- ↑ Lyman, p. 3

- 1 2 MacDonald, p. 105

- ↑ See Lyman for a description of the commission activities.

- ↑ MacDonald, pp. 105-106, 142, 173-183

- ↑ "Visit of Governor Samuel W. McCall of Massachusetts to Halifax, November 8-10, 1918". Nova Scotia Archives. Retrieved 2016-06-30.

- ↑ MacDonald, pp. 273-274

- ↑ Sobel, pp. 109-110

- ↑ United States Congress. "Samuel W. McCall (id: M000305)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

- ↑ "Governor Tom McCall's Administration". Oregon State Archives. Retrieved 2016-08-20.

Sources

- Abrams, Richard (1964). Conservatism in a Progressive Era: Massachusetts Politics 1900-1912. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. OCLC 475077.

- Evans, Lawrence Boyd (1916). Samuel McCall, Governor of Massachusetts. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin. OCLC 1926950.

- Gentile, Richard H (1999). "McCall, Samuel Walker". Dictionary of American National Biography. 14. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 835–837. ISBN 9780195206357. OCLC 39182280.

- Lyman, George Hinckley (1919). The story of the Massachusetts Committee on Public Safety : February 10, 1917-November 21, 1918. Boston: Massachusetts Committee on Public Safety. OCLC 5117307.

- MacDonald, Laura M (2005). Curse of the Narrows. New York: Walker & Company. ISBN 9780802714589. OCLC 748588928.

- Toomey, Daniel C; Quinn, Thomas P, eds. (1892). Massachusetts of To-Day: A Memorial of the State, Historical and Biographical, Issued for the World's Columbian exposition at Chicago. Boston: Columbia Publishing Company. OCLC 3251791.

- Sobel, Robert (1998). Coolidge: An American Enigma. Washington, DC: Regnery Publishing. ISBN 0895264102.

| United States House of Representatives | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Moses T. Stevens |

Member of the U.S. House of Representatives from Massachusetts's 8th congressional district March 4, 1893 – March 4, 1913 |

Succeeded by Frederick Simpson Deitrick |

| Political offices | ||

| Preceded by David I. Walsh |

Governor of Massachusetts 1916–1919 |

Succeeded by Calvin Coolidge |