Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act

.svg.png) | |

| Other short titles |

|

|---|---|

| Long title | An Act to enhance competition in the financial services industry by providing a prudential framework for the affiliation of banks, securities firms, and other financial service providers, and for other purposes. |

| Acronyms (colloquial) | GLBA |

| Nicknames | glibba, ATM Fee Reform Act of 1999 |

| Enacted by | the 106th United States Congress |

| Effective | November 12, 1999 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 106–102 |

| Statutes at Large | 113 Stat. 1338 |

| Codification | |

| Acts repealed | Glass–Steagall Act |

| Titles amended | |

| U.S.C. sections created |

12 U.S.C. § 24a, § 248b, § 1831v, § 1831w, § 1831x, § 1831y, § 1848a, § 2908 15 U.S.C. § 80b-10a |

| U.S.C. sections amended |

12 U.S.C. § 78, § 377 15 U.S.C. § 80 |

| Legislative history | |

| |

The Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act (GLBA), also known as the Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999, (Pub.L. 106–102, 113 Stat. 1338, enacted November 12, 1999) is an act of the 106th United States Congress (1999–2001). It repealed part of the Glass–Steagall Act of 1933, removing barriers in the market among banking companies, securities companies and insurance companies that prohibited any one institution from acting as any combination of an investment bank, a commercial bank, and an insurance company. With the bipartisan passage of the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act, commercial banks, investment banks, securities firms, and insurance companies were allowed to consolidate. Furthermore, it failed to give to the SEC or any other financial regulatory agency the authority to regulate large investment bank holding companies.[1] The legislation was signed into law by President Bill Clinton.[2]

A year before the law was passed, Citicorp, a commercial bank holding company, merged with the insurance company Travelers Group in 1998 to form the conglomerate Citigroup, a corporation combining banking, securities and insurance services under a house of brands that included Citibank, Smith Barney, Primerica, and Travelers. Because this merger was a violation of the Glass–Steagall Act and the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956, the Federal Reserve gave Citigroup a temporary waiver in September 1998.[3] Less than a year later, GLBA was passed to legalize these types of mergers on a permanent basis. The law also repealed Glass–Steagall's conflict of interest prohibitions "against simultaneous service by any officer, director, or employee of a securities firm as an officer, director, or employee of any member bank".[4]

Legislative history

The banking industry had been seeking the repeal of the 1933 Glass–Steagall Act since the 1980s, if not earlier.[5][6] In 1987 the Congressional Research Service prepared a report that explored the cases for and against preserving the Glass–Steagall act.[7]

Respective versions of the Financial Services Act were introduced in the U.S. Senate by Phil Gramm (Republican of Texas) and in the U.S. House of Representatives by Jim Leach (R-Iowa). The third lawmaker associated with the bill was Rep. Thomas J. Bliley, Jr. (R-Virginia), Chairman of the House Commerce Committee from 1995 to 2001.

During debate in the House of Representatives, Rep. John Dingell (Democrat of Michigan) argued that the bill would result in banks becoming "too big to fail." Dingell further argued that this would necessarily result in a bailout by the Federal Government.[8]

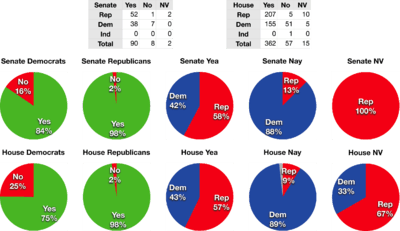

The House passed its version of the Financial Services Act of 1999 on July 1, 1999, by a bipartisan vote of 343–86 (Republicans 205–16; Democrats 138–69; Independent 0–1),[9][10][note 1] two months after the Senate had already passed its version of the bill on May 6 by a much-narrower 54–44 vote along basically-partisan lines (53 Republicans and 1 Democrat in favor; 44 Democrats opposed).[12][13][14][note 2]

When the two chambers could not agree on a joint version of the bill, the House voted on July 30 by a vote of 241–132 (R 58–131; D 182–1; Ind. 1–0) to instruct its negotiators to work for a law which ensured that consumers enjoyed medical and financial privacy as well as "robust competition and equal and non-discriminatory access to financial services and economic opportunities in their communities" (i.e., protection against exclusionary redlining).[note 3]

The bill then moved to a joint conference committee to work out the differences between the Senate and House versions. Democrats agreed to support the bill after Republicans agreed to strengthen provisions of the anti-redlining Community Reinvestment Act and address certain privacy concerns; the conference committee then finished its work by the beginning of November.[16][17] On November 4, the final bill resolving the differences was passed by the Senate 90–8,[18][note 4] and by the House 362–57.[19][note 5] The legislation was signed into law by President Bill Clinton on November 12, 1999.[20]

Changes caused by the Act

Many of the largest banks, brokerages, and insurance companies desired the Act at the time. The justification was that individuals usually put more money into investments when the economy is doing well, but they put most of their money into savings accounts when the economy turns bad. With the new Act, they would be able to do both 'savings' and 'investment' at the same financial institution, which would be able to do well in both good and bad economic times.

Prior to the Act, most financial services companies were already offering both saving and investment opportunities to their customers. On the retail/consumer side, a bank called Norwest Corporation which would later merge with Wells Fargo Bank led the charge in offering all types of financial services products in 1986. American Express attempted to own almost every field of financial business (although there was little synergy among them). Things culminated in 1998 when Citibank merged with Travelers Insurance creating CitiGroup. The merger violated the Bank Holding Company Act (BHCA), but Citibank was given a two-year forbearance that was based on an assumption that they would be able to force a change in the law. The Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act passed in November 1999, repealing portions of the BHCA and the Glass–Steagall Act, allowing banks, brokerages, and insurance companies to merge, thus making the CitiCorp/Travelers Group merger legal.

Also prior to the passage of the Act, there were many relaxations to the Glass–Steagall Act. For example, a few years earlier, commercial Banks were allowed to pursue investment banking, and before that banks were also allowed to begin stock and insurance brokerage. Insurance underwriting was the only main operation they weren't allowed to do, something rarely done by banks even after the passage of the Act. The Act further enacted three provisions that allow for bank holding companies to engage in physical commodity activities. Prior to the enactment of the Act those activities were limited to those that were so closely related to banking to be considered incidental to it. Under GLBA depending on the provision the institution falls into, bank holding companies can engage in physical commodity trading, energy tolling, energy management services, and merchant banking activities.[21]

Much consolidation occurred in the financial services industry since, but not at the scale some had expected. Retail banks, for example, do not tend to buy insurance underwriters, as they seek to engage in a more profitable business of insurance brokerage by selling products of other insurance companies. Other retail banks were slow to market investments and insurance products and package those products in a convincing way. Brokerage companies had a hard time getting into banking, because they do not have a large branch and backshop footprint. Banks have recently tended to buy other banks, such as the 2004 Bank of America and Fleet Boston merger, yet they have had less success integrating with investment and insurance companies. Many banks have expanded into investment banking, but have found it hard to package it with their banking services, without resorting to questionable tie-ins which caused scandals at Smith Barney.

Remaining restrictions

Crucial to the passing of this Act was an amendment made to the GLB, stating that no merger may go ahead if any of the financial holding institutions, or affiliates thereof, received a "less than satisfactory [sic] rating at its most recent CRA exam", essentially meaning that any merger may only go ahead with the strict approval of the regulatory bodies responsible for the Community Reinvestment Act (CRA).[22] This was an issue of hot contention, and the Clinton Administration stressed that it "would veto any legislation that would scale back minority-lending requirements." [23]

GLBA also did not remove the restrictions on banks placed by the Bank Holding Company Act of 1956 which prevented financial institutions from owning non-financial corporations. It conversely prohibits corporations outside of the banking or finance industry from entering retail and/or commercial banking. Many assume Wal-Mart's desire to convert its industrial bank to a commercial/retail bank ultimately drove the banking industry to back the GLBA restrictions.

Some restrictions remain to provide some amount of separation between the investment and commercial banking operations of a company. For example, licensed bankers must have separate business cards, e.g., "Personal Banker, Wells Fargo Bank" and "Investment Consultant, Wells Fargo Private Client Services". Much of the debate about financial privacy is specifically centered around allowing or preventing the banking, brokerage, and insurances divisions of a company from working together.

In terms of compliance, the key rules under the Act include The Financial Privacy Rule which governs the collection and disclosure of customers’ personal financial information by financial institutions. It also applies to companies, regardless of whether they are financial institutions, who receive such information. The Safeguards Rule requires all financial institutions to design, implement and maintain safeguards to protect customer information. The Safeguards Rule applies not only to financial institutions that collect information from their own customers, but also to financial institutions – such as credit reporting agencies, appraisers, and mortgage brokers – that receive customer information from other financial institutions.

Privacy

- GLBA compliance is mandatory; whether a financial institution discloses nonpublic information or not, there must be a policy in place to protect the information from foreseeable threats in security and data integrity.

- Major components put into place to govern the collection, disclosure, and protection of consumers’ nonpublic personal information; or personally identifiable information include:

Financial Privacy Rule

(Subtitle A: Disclosure of Nonpublic Personal Information, codified at 15 U.S.C. §§ 6801–6809)

The Financial Privacy Rule requires financial institutions to provide each consumer with a privacy notice at the time the consumer relationship is established and annually thereafter. The privacy notice must explain the information collected about the consumer, where that information is shared, how that information is used, and how that information is protected. The notice must also identify the consumer’s right to opt out of the information being shared with unaffiliated parties pursuant to the provisions of the Fair Credit Reporting Act. Should the privacy policy change at any point in time, the consumer must be notified again for acceptance. Each time the privacy notice is reestablished, the consumer has the right to opt out again. The unaffiliated parties receiving the nonpublic information are held to the acceptance terms of the consumer under the original relationship agreement. In summary, the financial privacy rule provides for a privacy policy agreement between the company and the consumer pertaining to the protection of the consumer’s personal nonpublic information.

On November 17, 2009, eight federal regulatory agencies released the final version of a model privacy notice form to make it easier for consumers to understand how financial institutions collect and share information about consumers.

Financial institutions

GLBA defines financial institutions as: "companies that offer financial products or services to individuals, like loans, financial or investment advice, or insurance". The Federal Trade Commission (FTC) has jurisdiction over financial institutions similar to, and including, these:

- Non-bank mortgage lenders,

- Real estate appraisers,

- Loan brokers,

- Some financial or investment advisers,

- Debt collectors,

- Tax return preparers,

- Banks, and

- Real estate settlement service providers.

These companies must also be considered significantly engaged in the financial service or production that defines them as a "financial institution".

Insurance has jurisdiction first by the state, provided the state law at minimum complies with the GLB. State law can require greater compliance, but not less than what is otherwise required by the GLB.

Consumer vs. customer defined

The Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act defines a "consumer" as

- "an individual who obtains, from a financial institution, financial products or services which are to be used primarily for personal, family, or household purposes, and also means the legal representative of such an individual." (See 15 U.S.C. § 6809(9).}

A customer is a consumer that has developed a relationship with privacy rights protected under the GLB. A customer is not someone using an automated teller machine (ATM) or having a check cashed at a cash advance business. These are not ongoing relationships like a customer might have—i.e., a mortgage loan, tax advising, or credit financing. A business is not an individual with personal nonpublic information, so a business cannot be a customer under the GLB. A business, however, may be liable for compliance to the GLB depending upon the type of business and the activities utilizing individual’s personal nonpublic information.

Definition: A "consumer" is an individual who obtains or has obtained a financial product or service from a financial institution that is to be used primarily for personal, family, or household purposes, or that individual's legal representative.Examples of consumer relationships:

- Applying for a loan

- Obtaining cash from a foreign ATM, even if it occurs on a regular basis

- Cashing a check with a check-cashing company

- Arranging for a wire transfer[24]

Definition: A "customer" is a consumer who has a "customer relationship" with a financial institution. A "customer relationship" is a continuing relationship with a consumer.Examples of establishing a customer relationship:

- Opening a credit card account with a financial institution

- Entering into an automobile lease (on a non-operating basis for an initial lease term of at least 90 days) with an automobile dealer

- Providing personally identifiable financial information to a broker in order to obtain a mortgage loan

- Obtaining a loan from a mortgage lender

- Agreeing to obtain tax preparation or credit counseling services

"Special Rule" for Loans: The customer relationship travels with ownership of the servicing rights.[24]

Consumer/client privacy rights

Under the GLB, financial institutions must provide their clients a privacy notice that explains what information the company gathers about the client, where this information is shared, and how the company safeguards that information. This privacy notice must be given to the client prior to entering into an agreement to do business. There are exceptions to this when the client accepts a delayed receipt of the notice in order to complete a transaction on a timely basis. This has been somewhat mitigated due to online acknowledgement agreements requiring the client to read or scroll through the notice and check a box to accept terms.

The privacy notice must also explain to the customer the opportunity to ‘opt-out’. Opting out means that the client can say "no" to allowing their information to be shared with affiliated parties. The Fair Credit Reporting Act is responsible for the ‘opt-out’ opportunity, but the privacy notice must inform the customer of this right under the GLB. The client cannot opt out of:

- information shared with those providing priority service to the financial institution

- marketing of products or services for the financial institution

- when the information is deemed legally required.

Safeguards Rule

(Subtitle A: Disclosure of Nonpublic Personal Information, codified at 15 U.S.C. §§ 6801–6809)

The Safeguards Rule requires financial institutions to develop a written information security plan that describes how the company is prepared for, and plans to continue to protect clients’ nonpublic personal information. (The Safeguards Rule applies to information of any consumers past or present of the financial institution's products or services.) This plan must include:

- Denoting at least one employee to manage the safeguards,

- Constructing a thorough risk analysis on each department handling the nonpublic information,

- Develop, monitor, and test a program to secure the information, and

- Change the safeguards as needed with the changes in how information is collected, stored, and used.

The Safeguards Rule forces financial institutions to take a closer look at how they manage private data and to do a risk analysis on their current processes. No process is perfect, so this has meant that every financial institution has had to make some effort to comply with the GLB.

Pretexting protection

(Subtitle B: Fraudulent Access to Financial Information, codified at 15 U.S.C. §§ 6821–6827)

Pretexting (sometimes referred to as "social engineering") occurs when someone tries to gain access to personal nonpublic information without proper authority to do so. This may entail requesting private information while impersonating the account holder, by phone, by mail, by email, or even by "phishing" (i.e., using a phony website or email to collect data). GLBA encourages the organizations covered by GLBA to implement safeguards against pretexting. For example, a well-written plan designed to meet GLB's Safeguards Rule ("develop, monitor, and test a program to secure the information") would likely include a section on training employees to recognize and deflect inquiries made under pretext. In fact, the evaluation of the effectiveness of such employee training probably should include a follow-up program of random spot-checks, "outside the classroom", after completion of the [initial] employee training, in order to check on the resistance of a given (randomly chosen) student to various types of "social engineering"—perhaps even designed to focus attention on any new wrinkle that might have arisen after the [initial] effort to "develop" the curriculum for such employee training. Under United States law, pretexting by individuals is punishable as a common law crime of False Pretenses.

Effect on usury law

Section 731 of the GLB, codified as subsection (f) of 12 U.S.C. § 1831u, contains a unique provision aimed at Arkansas, whose usury limit was set at five percent above the Federal Reserve discount rate by the Arkansas Constitution and could not be changed by the Arkansas General Assembly. When the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency ruled that interstate banks established under the Riegle-Neal Interstate Banking and Branching Efficiency Act of 1994 could use their home state's usury law for all branches nationwide with minimal restrictions,[25] Arkansas-based banks were placed at a severe competitive disadvantage to Arkansas branches of interstate banks; this led to out-of-state takeovers of several Arkansas banks, including the sale of First Commercial Bank (then Arkansas' largest bank) to Regions Financial Corporation in 1998.

Under Section 731, all banks headquartered in a state covered by that law may charge up to the highest usury limit of any state that is headquarters to an interstate bank which has branches in the covered state. Therefore, since Arkansas has branches of banks based in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, Missouri, North Carolina, Ohio, and Texas,[26] any loan that is legal under the usury laws of any of those states may be made by an Arkansas-based bank under Section 731. The section does not apply to interstate banks with branches in the covered state, but headquartered elsewhere; however, Arkansas-based interstate banks like Arvest Bank may export their Section 731 limits to other states.

Due to Section 731, it is generally regarded that Arkansas-based banks now have no usury limit for credit cards or for any loan of greater than $2,000 (since Alabama, Regions' home state, has no limits on those loans), with a limit of 18% (the minimum usury limit in Texas) or more on all other loans.[27] However, once Wells Fargo fully completed its purchase of Century Bank (a Texas bank with Arkansas branches), Section 731 did away with all usury limits for Arkansas-based banks since Wells Fargo's main bank charter is based in South Dakota, which repealed its usury laws many years ago.

Though designed for Arkansas, Section 731 may also apply to Alaska and California whose constitutions provide for the same basic usury limit, though unlike Arkansas their legislatures can (and generally do) set different limits. If Section 731 applies to those states, then all their usury limits are inapplicable to banks based in those states, since Wells Fargo has branches in both states.

Controversy

Criticisms

The act is "often cited as a cause" of the 2007 subprime mortgage financial crisis "even by some of its onetime supporters."[28] President Barack Obama has stated that GLBA led to deregulation that, among other things, allowed for the creation of giant financial supermarkets that could own investment banks, commercial banks and insurance firms, something banned since the Great Depression. Its passage, critics also say, cleared the way for companies that were too big and intertwined to fail.[29]

Nobel Prize-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz has also argued that the Act helped to create the crisis.[30] In an article in The Nation, Mark Sumner asserted that the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act was responsible for the creation of entities that took on more risk due to their being considered “too big to fail".[31] Other critics also assert that proponents and defenders of the Act espouse a form of "eliteconomics" that has, with the passage of the Act, directly precipitated the current economic recession while at the same time shifting the burden of belt-tightening measures onto the lower- and middle-income classes.[32]

According to a 2009 policy report from the Cato Institute authored by one of the institute's directors, Mark A. Calabria, critics of the legislation feared that, with the allowance for mergers between investment and commercial banks, GLBA allowed the newly-merged banks to take on riskier investments while at the same time removing any requirements to maintain enough equity, exposing the assets of its banking customers.[33] Calabria claimed that, prior to the passage of GLBA in 1999, investment banks were already capable of holding and trading the very financial assets claimed to be the cause of the mortgage crisis, and were also already able to keep their books as they had.[33] He concluded that greater access to investment capital as many investment banks went public on the market explains the shift in their holdings to trading portfolios.[33] Calabria noted that after GLBA passed, most investment banks did not merge with depository commercial banks, and that in fact, the few banks that did merge weathered the crisis better than those that did not.[33]

In February 2009, one of the act's co-authors, former Senator Phil Gramm, also defended his bill:

[I]f GLB was the problem, the crisis would have been expected to have originated in Europe where they never had Glass–Steagall requirements to begin with. Also, the financial firms that failed in this crisis, like Lehman, were the least diversified and the ones that survived, like J.P. Morgan, were the most diversified. Moreover, GLB did not deregulate anything. It established the Federal Reserve as a superregulator, overseeing all Financial Services Holding Companies. All activities of financial institutions continued to be regulated on a functional basis by the regulators that had regulated those activities prior to GLB.[34]

Bill Clinton, as well as economists Brad DeLong and Tyler Cowen have all argued that the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act softened the impact of the crisis.[35][36] Atlantic Monthly columnist Megan McArdle has argued that if the act was "part of the problem, it would be the commercial banks, not the investment banks, that were in trouble" and repeal would not have helped the situation.[37] An article in the conservative publication National Review has made the same argument, calling liberal allegations about the Act “folk economics.”[38] A New York Times financial columnist and occasional critic of GLBA stated that he believes GLBA had little to do with the failed institutions.[39]

Amendments

Proposed

- National Association of Registered Agents and Brokers Reform Act of 2013 (H.R. 1155; 113th Congress) (H

.R ) is a bill meant to reduce the regulatory costs of complying with multiple states' requirements for insurance companies, making it easier for the same company to operate in multiple states.[40] The bill would amend the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act to repeal the contingent conditions under which the National Association of Registered Agents and Brokers (NARAB) shall not be established.[41] The bill would transform the National Association of Registered Agents and Brokers (NARAB) into a clearing house that set up its own standards that insurance companies would be required to meet in order to do business in other states.[40] In this new system, however, the insurance company would only have to meet the requirements of their home state and the NARAB (only two entities), not their home state and every other state they wished to operate in (multiple entities).[40] Proponents of the bill argued that it would help lower costs for insurance companies and make insurance cheaper for people to buy.. 1155

See also

- Bank regulation

- Securities regulation in the United States

- Commodity Futures Trading Commission

- Securities Commission

- Chicago Stock Exchange

- Financial regulation

- Inside Job (2010 documentary film)

- List of financial regulatory authorities by country

- NASDAQ

- New York Stock Exchange

- Stock exchange

- Regulation D (SEC)

- Related legislation

- 1933 – Securities Act of 1933

- 1933 – Banking Act of 1933, which contained legislation repealed by Gramm–Leach–Bliley

- 1934 – Securities Exchange Act of 1934

- 1938 – Temporary National Economic Committee (establishment)

- 1939 – Trust Indenture Act of 1939

- 1940 – Investment Advisers Act of 1940

- 1940 – Investment Company Act of 1940

- 1968 – Williams Act (Securities Disclosure Act)

- 1975 – Securities and Exchange Act

- 1982 – Garn–St. Germain Depository Institutions Act

- 2000 – Commodity Futures Modernization Act of 2000

- 2002 – Sarbanes–Oxley Act

- 2003 – Fair and Accurate Credit Transactions Act of 2003

- 2006 – Credit Rating Agency Reform Act of 2006

- 2010 – Dodd–Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act

Notes

- ↑ Two Republicans and four Democrats did not vote.[11]

- ↑ Sen. Fritz Hollings (D-S. Carolina) voted in favor, Sen. Peter Fitzgerald (R-Illinois) voted "present" and Sen. James Inhofe (R-Oklahoma) did not vote. A table with members' full names, sortable by vote, state, region and party, may be found at S.900 as amended: Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act, roll call 105, 106th Congress, 1st session. Votes Database at The Washington Post. Retrieved on 2008-10-09 from http://projects.washingtonpost.com/congress/106/senate/1/votes/105/.

- ↑ Independent-Socialist Rep. Bernard Sanders of Vermont voted yes; 33 Republicans and 28 Democrats did not vote.[15]

- ↑ 52 Republicans and 38 Democrats voted for the bill. Sen. Richard Shelby of Alabama (Republican, formerly a Democrat) voted against it, as did 7 Democratic Senators: Barbara Boxer (Calif.), Richard Bryan (Nevada), Byron Dorgan (N. Dakota), Russell Feingold (Wisc.), Tom Harkin (Iowa), Barbara Mikulski (Maryland) and Paul Wellstone (Minn.) Sen. Peter Fitzgerald (R-Illinois) again voted "present", while Sen. John McCain (R-Arizona) did not vote.

- ↑ Republicans voted 207–5 in favor with 10 not voting. Democrats voted 155–51 in favor, with 5 not voting. Independent-Socialist Rep. Bernard Sanders of Vermont voted no.

References

- ↑ Chairman Cox (September 26, 2008). "Chairman Cox Announces End of Consolidated Supervised Entities Program". press release 2008-230. SEC. Retrieved 14 March 2014.

- ↑ Peters, Gerhard; Woolley, John T. "William J. Clinton: "Statement on Signing the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act," November 12, 1999". The American Presidency Project. University of California – Santa Barbara.

- ↑ Broome, Lissa Lamkin; & Markham, Jerry W. (2001). The Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act: An Overview. Retrieved from http://www.symtrex.com/pdfdocs/glb_paper.pdf.

- ↑ "Bill Summary & Status 106th Congress (1999–2000) S.900 CRS Summary – Thomas (Library of Congress)". Retrieved 2011-02-08.

- ↑ Shanny Basar (November 9, 2012). "John Reed, Vikram Pandit Re-Consider Glass-Steagall 10 Years". Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Corinne Crawford; Borough of Manhattan Community College (January 2011). "The Repeal Of The Glass- Steagall Act And The Current Financial Crisis" (PDF). Journal of Business & Economics Research. pp. 127–133.

- ↑ IB87061: Glass-Steagall Act: Commercial vs. Investment Banking, Congressional Research Service (CRS)

- ↑ John Dingell (Nov 4, 1999). House Session (Flash) (Television production). Washington, DC: C-SPAN. Event occurs at 03:02:11. Program ID 153391-1.

- ↑ H.R.10: Financial Services Act of 1999, EH, July 1, 1999, Engrossed as Agreed to or Passed by House, Library of Congress

- ↑ Consideration of H.R.10: Financial Services Act of 1999, All Congressional Actions & Reports of H.R.10, Congressional Record

- ↑ Congressional roll-call: H.R.10 as amended: Financial Services Act of 1999, Record Vote No: 276, July 1, 1999, Clerk of the United States House of Representatives

- ↑ S.900: Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999, ES, May 6, 1999, Engrossed as Agreed to or Passed by Senate, Library of Congress

- ↑ Consideration of S.900: Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999, All Congressional Actions & Reports of S.900, Congressional Record

- ↑ Congressional roll-call at S.900 as amended: Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999, Record Vote No: 105, May 6, 1999, U.S. Senate Roll Call Votes.

- ↑ Congressional roll-call: On Motion to Instruct Conferees – S.900: Financial Services Modernization Act of 1999, Record Vote No: 355, July 30, 1999, Clerk of the U.S. House. Sortable unofficial table: On Motion to Instruct Conferees, Financial Services Modernization Act, roll call 355, 106th Congress, 1st session, Votes Database at The Washington Post, retrieved on October 12, 2008.

- ↑ "Republicans' Revised Banking Bill Greeted With Veto Promise", Washington Post, October 13, 1999, p.E03

- ↑ The War on CRA: Opportunity in Next Wave of Mergers, Cincotta, National Housing Institute, 1999

- ↑ Congressional roll-call: S.900 as reported by conferees: Financial Services Act of 1999, Record Vote No: 354, November 4, 1999, Clerk of the Senate. Sortable unofficial table: On Agreeing to the Conference Report, S.900 Gramm–Bliley–Leach Act, roll call 354, 106th Congress, 1st session Votes Database at The Washington Post, retrieved on October 9, 2008

- ↑ Congressional roll-call: On the passage of S.900: Financial Services Act of 1999, Record Vote No: 570, November 4, 1999, Clerk of the U.S. House. Sortable unofficial table: On Agreeing to the Conference Report, S. 900 Financial Services Modernization Act, roll call 570, 106th Congress, 1st session Votes Database at The Washington Post, retrieved on October 9, 2008

- ↑ "S. 900: Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act", 106th Congress – 1st Session, GovTrack.us.

- ↑ "Physical commodity activities: Too risky for banking organizations?" (PDF). http://www.pwc.com/us/en/financial-services/regulatory-services/publications/frb-physical-commodities-anpr.jhtml. PwC Financial Services Regulatory Practice, January, 2014. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Community Reinvestment Act Amendments in the Gramm–Leach Act, additional text.

- ↑ Compromise over Community Reinvestment Act crucial to repeal of Glass-Steagall

- 1 2 FTC (June 18, 2001). "The Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act Privacy of Consumer Financial Information". Federal Trade Commission Bureau of Consumer Protection Division of Financial Practices. FTC. Retrieved 25 October 2011.

- ↑ http://www.occ.gov/interp/mar98/int822.pdf

- ↑ http://www.arkansas.gov/bank/authority.html

- ↑ http://www.arkbar.com/Ark_Lawyer_Mag/Articles/UsuryWinter04.html

- ↑ Leonhardt, David. Washington’s Invisible Hand, September 26, 2008 New York Times

- ↑ Ten Questions for Those Fixing the Financial Mess. Wall Street Journal. March 10, 2009.

- ↑ Who's Whining Now? Gramm Slammed By Economists. ABC News. Sept. 19, 2008.

- ↑ Sumner, Mark – John McCain: Crisis Enabler. The Nation. September 21, 2008.

- ↑ DeGraw, David (2010-02-15). "The Economic Elite Vs. The People of the United States of America – Part I". Ampedstatus.com. Retrieved 2012-05-20.

- 1 2 3 4 Calabria, Mark A. (July–August 2009). "Did Deregulation Cause the Financial Crisis?" (PDF). Cato Institute. Retrieved 2009-07-28.

- ↑ Phil Gramm, "Deregulation and the Financial Panic", opinion pages of The Wall Street Journal, published and retrieved on February 20, 2009

- ↑ Who Caused the Economic Crisis?. FactCheck.org October 1, 2008.

- ↑ Bartiromo, Maria (2008-09-23). "Bill Clinton on the Banking Crisis, McCain, and Hillary". Bloomberg Business. Retrieved 2016-02-02.

- ↑ Hindsight regulation. Megan McArdle. Atlantic Monthly. September 16, 2008

- ↑ Villain Phil. National Review. September 22, 2008.

- ↑ Andrew Ross Sorkin (May 22, 2012). "Reinstating an Old Rule Is Not a Cure for Crisis". New York Times.

- 1 2 3 Kasperowicz, Pete (10 September 2013). "House votes to streamline cross-state insurance sales". The Hill. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

- ↑ "H.R. 1155 – Summary". United States Congress. Retrieved 11 September 2013.

Sources

- Financial Privacy: The Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act, Federal Trade Commission, 1999

- Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act,15 USC, Subchapter I, Sec. 6801–6809, Disclosure of Nonpublic Personal Information, FTC, 1999

- Mike Chapple, Gramm–Leach–Bliley and You, November 18, 2003

- Robert H. Ledig, Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act Financial Privacy Provisions:The Federal Government Imposes Broad Requirements to Address Consumer Privacy Concerns

- The Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act: The Financial Privacy Rule, Federal Trade Commission

- In Brief: The Financial Privacy Requirements of the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act, Federal Trade Commission

- The Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act — “History of the GLBA”, Electronic Privacy Information Center

- Financial Institution Privacy Protection Act of 2003 — 108th CONGRESS, 1st Session, S. 1458, “To amend the Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act to provide for enhanced protection of nonpublic personal information, including health information, and for other purposes.”, In the Senate of the United States; July 25 (legislative day, JULY 21), 2003, Library of Congress

- Testimony of (Federal Reserve) Governor Laurence H. Meyer: Merchant banking, Federal Reserve Bank

- Martin McLaughlin, Clinton, Republicans agree to deregulation of US financial system, World Socialist Web Site, November 1, 1999, retrieved on October 9, 2008

External links

Compliance information

Consumer/client rights information

- Disclosure of Nonpublic Personal Information

- What Can You Do To Protect Your Privacy

- Privacy Choices for Your Personal Financial Information

- Pretexting: Your Personal Information Revealed

History of the GLB

Congressional voting records on Gramm–Leach–Bliley Act

- Senate Vote #354 (Nov. 4, 1999) On the Conference Report (S.900 Conference Report )

- House Vote #570 (Nov. 4, 1999) On Agreeing to the Conference Report: S 900 (106th) Financial Services Modernization Act