Rudd Concession

|

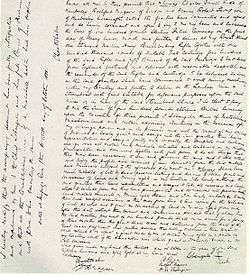

A photograph of the concession document | |

| Signed | 30 October 1888 |

|---|---|

| Location | Bulawayo, Matabeleland |

| Depositary | British South Africa Company (from 1890) |

|

| |

The Rudd Concession, a written concession for exclusive mining rights in Matabeleland, Mashonaland and other adjoining territories in what is today Zimbabwe, was granted by King Lobengula of Matabeleland to Charles Rudd, James Rochfort Maguire and Francis Thompson, three agents acting on behalf of the South African-based politician and businessman Cecil Rhodes, on 30 October 1888. Despite Lobengula's retrospective attempts to disavow it, it proved the foundation for the royal charter granted by the United Kingdom to Rhodes's British South Africa Company in October 1889, and thereafter for the Pioneer Column's occupation of Mashonaland in 1890, which marked the beginning of white settlement, administration and development in the country that eventually became Rhodesia, named after Rhodes, in 1895.

Rhodes's pursuit of the exclusive mining rights in Matabeleland, Mashonaland and the surrounding areas was motivated by his wish to annex them into the British Empire as part of his personal ambition for a Cape to Cairo Railway—winning the concession would enable him to gain a royal charter from the British government for a chartered company, empowered to annex and thereafter govern the Zambezi–Limpopo watershed on Britain's behalf. He laid the groundwork for concession negotiations during early 1888 by arranging a treaty of friendship between the British and Matabele peoples[n 1] and then sent Rudd's team from South Africa to obtain the rights. Rudd succeeded following a race to the Matabele capital Bulawayo against Edward Arthur Maund, a bidding-rival employed by a London-based syndicate, and after long negotiations with the king and his council of izinDuna (tribal leaders).

The concession conferred on the grantees the sole rights to mine throughout Lobengula's country, as well as the power to defend this exclusivity by force, in return for weapons and a regular monetary stipend. Starting in early 1889, the king repeatedly tried to disavow the document on the grounds of alleged deceit by the concessionaires regarding the settled terms; he insisted that restrictions on the grantees' activities had been agreed orally, and apparently considered these part of the contract even though the written text had been translated and repeatedly explained to him just before he signed it. He attempted to persuade the British government to deem the concession invalid, among other things sending emissaries to meet Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle, but these efforts proved unsuccessful.

After Rhodes and the London consortium agreed to pool their interests, Rhodes travelled to London, arriving in March 1889. His amalgamated charter bid gathered great political and popular support over the next few months, prompting the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, to approve the royal charter, which was formally granted in October 1889. The Company occupied and annexed Mashonaland about a year later. Attempting to set up a rival to the Rudd Concession, Lobengula granted similar rights to the German businessman Eduard Lippert in 1891, but Rhodes promptly acquired this concession as well. Company troops conquered Matabeleland during the First Matabele War of 1893–1894, and Lobengula died from smallpox in exile soon after.

Background

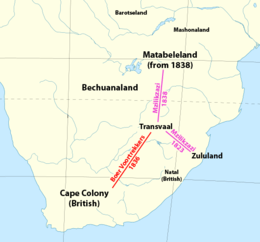

During the 1810s, the Zulu Kingdom was established in southern Africa by the warrior king Shaka, who united a number of rival clans into a centralised monarchy. Among the Zulu Kingdom's main leaders and military commanders was Mzilikazi, who enjoyed high royal favour for a time, but ultimately provoked the king's wrath by repeatedly offending him. When Shaka forced Mzilikazi and his followers to leave the country in 1823, they moved north-west to the Transvaal, where they became known as the Ndebele or "Matabele"[n 1]—both names mean "men of the long shields".[2] Amid the period of war and chaos locally called mfecane ("the crushing"), the Matabele quickly became the region's dominant tribe.[3] In 1836, they negotiated a peace treaty with Sir Benjamin d'Urban, Governor of the British Cape Colony,[4] but the same year Boer Voortrekkers moved to the area, during their Great Trek away from British rule in the Cape. These new arrivals soon toppled Mzilikazi's domination of the Transvaal, compelling him to lead another migration north in 1838. Crossing the Limpopo River, the Matabele settled in the Zambezi–Limpopo watershed's south-west; this area has since been called Matabeleland.[3]

Matabele culture mirrored that of the Zulus in many aspects. The Matabele language, Sindebele, was largely based on Zulu—and just like Zululand, Matabeleland had a strong martial tradition. Matabele men went through a Spartan upbringing, designed to produce disciplined warriors, and military organisation largely dictated the distribution of administrative responsibilities. The inkosi (king) appointed a number of izinDuna (or indunas), who acted as tribal leaders in both military and civilian matters. Like the Zulus, the Matabele referred to a regiment of warriors as an impi. The Mashona people, who had inhabited the north-east of the region for centuries, greatly outnumbered the Matabele, but were weaker militarily, and so to a large degree entered a state of tributary submission to them.[5] Mzilikazi agreed to two treaties with the Transvaal Boers in 1853, first with Hendrik Potgieter (who died shortly before negotiations ended), then with Andries Pretorius; the first of these, which did not bear Mzilikazi's own mark, purported to make Matabeleland a virtual Transvaal protectorate, while the second, which was more properly enacted, comprised a more equal peace agreement.[6]

After Mzilikazi died in 1868, his son Lobengula replaced him in 1870, following a brief succession struggle.[7] Tall and well built, Lobengula was generally considered thoughtful and sensible, even by contemporary Western accounts; according to the South African big-game hunter Frederick Hugh Barber, who met him in 1875, he was witty, mentally sharp and authoritative—"every inch a king".[8] Based at his royal kraal at Bulawayo,[n 2] Lobengula was at first open to Western enterprises in his country, adopting Western-style clothing and granting mining concessions and hunting licences to white visitors in return for pounds sterling, weapons and ammunition. Because of the king's illiteracy, these documents were prepared in English or Dutch by whites who took up residence at his kraal; to ascertain that what was written genuinely reflected what he had said, Lobengula would have his words translated and transcribed by one of the whites, then later translated back by another. Once the king was satisfied of the written translation's veracity, he would sign his mark, affix the royal seal (which depicted an elephant), and then have the document signed and witnessed by a number of white men, at least one of whom would also write an endorsement of the proclamation.[10]

For unclear reasons, Lobengula's attitude towards foreigners reversed sharply during the late 1870s. He discarded his Western clothes in favour of more traditional animal-skin garments, stopped supporting trading enterprises,[10] and began to restrict the movement of whites into and around his country. However, the whites kept coming, particularly after the discovery in 1886 of gold deposits in the South African Republic (or Transvaal), which prompted the Witwatersrand Gold Rush and the founding of Johannesburg. After rumours spread among the Witwatersrand (or Rand) prospectors of even richer tracts, "a second Rand", north of the Limpopo, the miners began to trek north to seek concessions from Lobengula that would allow them to search for gold in Matabeleland and Mashonaland.[11] These efforts were mostly in vain. Apart from the Tati Concession, which covered a small strip of land on the border with the Bechuanaland Protectorate where miners had operated since 1868,[12] mining operations in the watershed remained few and far between.[11]

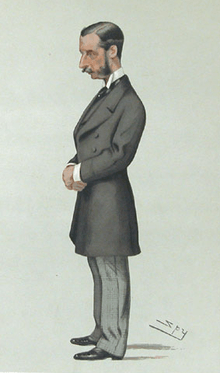

The foremost business and political figure in southern Africa at this time was Cecil Rhodes, a vicar's son who had arrived from England in 1870, aged 17.[13] Since entering the diamond trade at Kimberley in 1871, Rhodes had gained near-complete domination of the world diamond market with the help of Charles Rudd, Alfred Beit and other business associates, as well as the generous financial backing of Nathan Mayer Rothschild.[14] Rhodes was also a member of the Cape Parliament, having been elected in 1881.[15] Amid the European Scramble for Africa, he envisioned the annexation to the British Empire of territories that would connect the Cape, at Africa's southern tip, with Cairo, the Egyptian city at the northern end of the continent, and allow for the construction of a railway linking the two. This ambition was directly challenged in the south by the presence of the Boer republics and, just to the north of them, Lobengula's domains.[16] The fact that the Zambezi–Limpopo region did not fall into any of the "spheres of influence" defined at the 1884–85 Berlin Conference further complicated matters; the Transvaalers, Germans and Portuguese were all also showing interest in the area, much to the annoyance of both Lobengula and Rhodes.[17]

Prelude: the Moffat treaty

Rhodes began advocating the annexation by Britain of Matabeleland and Mashonaland in 1887 by applying pressure to a number of senior colonial officials, most prominently the High Commissioner for Southern Africa, Sir Hercules Robinson, and Sidney Shippard, Britain's administrator in the Bechuanaland Crown colony (comprising that country's southern part). Shippard, an old friend of Rhodes,[17] was soon won over to the idea, and in May 1887 the administrator wrote to Robinson strongly endorsing annexation of the territories, particularly Mashonaland, which he described as "beyond comparison the most valuable country south of the Zambezi".[18] It was the Boers, however, who were first to achieve diplomatic successes with Lobengula. Pieter Grobler secured a treaty of "renewal of friendship" between Matabeleland and the South African Republic in July 1887.[n 3] The same month, Robinson organised the appointment of John Smith Moffat, a locally born missionary, as assistant commissioner in Bechuanaland.[20] Moffat, well-known to Lobengula, was given this position in the hope that he might make the king less cordial with the Boers and more pro-British.[21][n 4]

In September 1887, Robinson wrote to Lobengula, through Moffat, urging the king not to grant concessions of any kind to Transvaal, German or Portuguese agents without first consulting the missionary.[21] Moffat reached Bulawayo on 29 November to find Grobler still there. Because the exact text of the Grobler treaty had not been released publicly, it was unclear to outside observers precisely what had been agreed with Lobengula in July; in the uncertainty, newspapers in South Africa were reporting that the treaty had made Matabeleland a protectorate of the South African Republic. Moffat made enquiries in Bulawayo. Grobler denied the newspaper reports of a Transvaal protectorate over Lobengula's country, while the king said that an agreement did exist, but that it was a renewal of the Pretorius peace treaty and nothing more.[21]

In Pretoria, in early December, another British agent met Paul Kruger, the President of the South African Republic, who reportedly said that his government now regarded Matabeleland as under Transvaal "protection and sovereignty", and that one of the clauses of the Grobler treaty had been that Lobengula could not "grant any concessions or make any contact with anybody whatsoever" without Pretoria's approval.[23] Meeting at Grahamstown on Christmas Day, Rhodes, Shippard and Robinson agreed to instruct Moffat to investigate the matter with Lobengula and to secure a copy of the Grobler treaty for further clarification, as well as to arrange a formal Anglo-Matabele treaty, which would have provisions included to prevent Lobengula from making any more agreements with foreign powers other than Britain.[23]

Lobengula was alarmed by how some were perceiving his dealings with Grobler, and so was reluctant to sign any more agreements with foreigners. Despite his familiarity with Moffat, the king did not consider him above suspicion, and he was dubious about placing himself firmly in the British camp; as Moffat said of the Matabele leadership in general, "they may like us better, but they fear the Boers more".[23] Moffat's negotiations with the king and izinDuna were therefore very long and uneasy. The missionary presented the proposed British treaty as an offer to renew that enacted by d'Urban and Mzilikazi in 1836.[4] He told the Matabele that the Boers were misleading them, that Pretoria's interpretation of the Grobler treaty differed greatly from their own, and that the British proposal served Matabele interests better in any case.[24] On 11 February 1888, Lobengula agreed and placed his mark and seal at the foot of the agreement.[24] The document proclaimed that the Matabele and British were now at peace, that Lobengula would not enter any kind of diplomatic correspondence with any country apart from Britain, and that the king would not "sell, alienate or cede" any part of Matabeleland or Mashonaland to anybody.[25]

The document was unilateral in form, describing only what Lobengula would do to prevent any of these conditions being broken. Shippard was dubious about this and the fact that none of the izinDuna had signed the proclamation, and asked Robinson if it would be advisable to negotiate another treaty. Robinson replied in the negative, reasoning that reopening talks with Lobengula so soon would only make him suspicious. Britain's ministers at Whitehall perceived the unilateral character of the treaty as advantageous for Britain, as it did not commit Her Majesty's Government to any particular course of action. Lord Salisbury, the British Prime Minister, ruled that Moffat's treaty trumped Grobler's, despite being signed at a later date, because the London Convention of 1884 precluded the South African Republic from making treaties with any state apart from the Orange Free State; treaties with "native tribes" north of the Limpopo were permitted, but the Prime Minister claimed that Matabeleland was too cohesively organised to be regarded as a mere tribe, and should instead be considered a nation. He concluded from this reasoning that the Grobler treaty was ultra vires and legally meaningless. Whitehall soon gave Robinson permission to ratify the Moffat agreement, which was announced to the public in Cape Town on 25 April 1888.[25]

For Rhodes, the agreement Moffat had made with Lobengula was crucial as it bought time that allowed him to devote the necessary attention to the final amalgamation of the South African diamond interests. A possible way out of the situation for Lobengula was to lead another Matabele migration across the Zambezi, but Rhodes hoped to keep the king where he was for the moment as a buffer against Boer expansion.[26] In March 1888, Rhodes bought out the company of his last competitor, the circus showman turned diamond millionaire Barney Barnato, to form De Beers Consolidated Mines, a sprawling national monopoly that controlled 90% of world diamond production.[27] Barnato wanted to limit De Beers to mining diamonds, but Rhodes insisted that he was going to use the company to "win the north": to this end, he ensured that the De Beers trust deed enabled activities far removed from mining, including banking and railway-building, the ability to annex and govern land, and the raising of armed forces.[28] All this gave the immensely wealthy company powers not unlike those of the East India Company, which had governed India on Britain's behalf from 1757 to 1857.[29] Through De Beers and Gold Fields of South Africa, the gold-mining firm he had recently started with Charles Rudd, Rhodes had both the capacity and the financial means to make his dream of an African empire a reality, but to make such ambitions practicable,[28] he would first have to acquire a royal charter empowering him to take personal control of the relevant territories on Britain's behalf.[30] To secure this royal charter, he would need to present Whitehall with a concession, signed by a native ruler, granting to Rhodes the exclusive mining rights in the lands he hoped to annex.[28]

Concession

Race to Bulawayo

Rhodes faced competition for the Matabeleland mining concession from George Cawston and Lord Gifford, two London financiers. They appointed as their agent Edward Arthur Maund, who had served with Sir Charles Warren in Bechuanaland between 1884 and 1885, towards the end of this time visiting Lobengula as an official British envoy. Cawston and Gifford's base in England gave them the advantage of better connections with Whitehall, while Rhodes's location in the Cape allowed him to see the situation with his own eyes. He also possessed formidable financial capital and closer links with the relevant colonial administrators. In May 1888, Cawston and Gifford wrote to Lord Knutsford, the British Colonial Secretary, seeking his approval for their designs.[31]

The urgency of negotiating a concession was made clear to Rhodes during a visit to London in June 1888, when he learned of the London syndicate's letter to Knutsford, and of their appointment of Maund. Rhodes now understood that the Matabeleland concession could still go elsewhere if he did not secure the document quickly.[32][n 5] "Someone has to get the country, and I think we should have the best chance," Rhodes told Rothschild; "I have always been afraid of the difficulty of dealing with the Matabele king. He is the only block to central Africa, as, once we have his territory, the rest is easy ... the rest is simply a village system with separate headmen ... I have faith in the country, and Africa is on the move. I think it is a second Cinderella."[34]

Rhodes and Beit put Rudd at the head of their new negotiating team because of his extensive experience negotiating the purchase of Boers' farms for gold prospecting. Because Rudd knew little of indigenous African customs and languages, Rhodes added Francis "Matabele" Thompson, an employee of his who had for years run the reserves and compounds that housed the black labourers at the diamond fields. Thompson was fluent in Setswana, the language of the Tswana people to Lobengula's south-west, and therefore could communicate directly and articulately with the king, who also knew the language. James Rochfort Maguire, an Irish barrister Rhodes had known at Oxford, was recruited as a third member.[35]

Many analysts find the inclusion of the cultured, metropolitan Maguire puzzling—it is often suggested that he was brought along so he could couch the document in the elaborate legal language of the English bar, and thus make it unchallengeable,[34] but as the historian John Galbraith comments, the kind of agreement that was required was hardly complicated enough to merit the considerable expense and inconvenience of bringing Maguire along.[35] In his biography of Rhodes, Robert I Rotberg suggests that he may have intended Maguire to lend Rudd's expedition "a touch of culture and class",[34] in the hope that this might impress Lobengula and rival would-be concessionaires. One of the advantages held by the London syndicate was the societal prestige of Gifford in particular, and Rhodes hoped to counter this through Maguire.[34] Rudd's party ultimately comprised himself, Thompson, Maguire, J G Dreyer (their Dutch wagon driver), a fifth white man, a Cape Coloured, an African American and two black servants.[36]

Maund arrived in Cape Town in late June 1888 and attempted to gain Robinson's approval for the Cawston–Gifford bid. Robinson was reserved in his answers, saying that he supported the development of Matabeleland by a company with this kind of backing, but did not feel he could commit to endorsing Cawston and Gifford exclusively while there remained other potential concessionaires, most prominently Rhodes—certainly not without unequivocal instructions from Whitehall. While Rudd's party gathered and prepared in Kimberley, Maund travelled north, and reached the diamond mines at the start of July.[37] On 14 July, in Bulawayo, agents representing a consortium headed by the South African-based entrepreneur Thomas Leask received a mining concession from Lobengula,[38] covering all of his country, and pledging half of the proceeds to the king. When he learned of this latter condition Leask was distraught, saying the concession was "commercially valueless".[39] Moffat pointed out to Leask that his group did not have the resources to act on the concession anyway, and that both Rhodes and the London syndicate did; at Moffat's suggestion, Leask decided to wait and sell his concession to whichever big business group gained a new agreement from Lobengula. Neither Rhodes's group, the Cawston–Gifford consortium nor the British colonial officials immediately learned of the Leask concession.[39]

In early July 1888, Rhodes returned from London and met with Robinson, proposing the establishment of a chartered company to govern and develop south-central Africa, with himself at its head, and similar powers to the British North Borneo, Imperial British East Africa and Royal Niger Companies. Rhodes said that this company would take control of those parts of Matabeleland and Mashonaland "not in use" by the local people, demarcate reserved areas for the indigenous population, and thereafter defend both, while developing the lands not reserved for natives. In this way, he concluded, Matabele and Mashona interests would be protected, and south-central Africa would be developed, all without a penny from Her Majesty's Treasury. Robinson wrote to Knutsford on 21 July that he thought Whitehall should back this idea; he surmised that the Boers would receive British expansion into the Zambezi–Limpopo watershed better if it came in the form of a chartered company than if it occurred with the creation of a new Crown colony.[40] He furthermore wrote a letter for Rudd's party to carry to Bulawayo, recommending Rudd and his companions to Lobengula.[41]

Maund left Kimberley in July, well ahead of the Rudd party.[40] Rudd's negotiating team, armed with Robinson's endorsement, was still far from ready—they left Kimberley only on 15 August—but Moffat, travelling from Shoshong in Bechuanaland, was ahead of both expeditions. He reached Bulawayo in late August to find the kraal filled with white concession-hunters.[34] The various bidders attempted to woo the king with a series of gifts and favours, but won little to show for it.[42]

Between Kimberley and Mafeking, Maund learned from Shippard that Grobler had been killed by a group of Ngwato warriors while returning to the Transvaal, and that the Boers were threatening to attack the British-protected Ngwato chief, Khama III, in response. Maund volunteered to help defend Khama, writing a letter to his employers explaining that doing so might lay the foundations for a concession from Khama covering territory that the Matabele and Ngwato disputed. Cawston tersely wrote back with orders to make for Bulawayo without delay, but over a month had passed in the time this written exchange required, and Maund had squandered his head start on Rudd.[43] After ignoring a notice Lobengula had posted at Tati, barring entry to white big-game hunters and concession-seekers,[44] the Rudd party arrived at the king's kraal on 21 September 1888, three weeks ahead of Maund.[42]

Negotiations

Rudd, Thompson and Maguire immediately went to present themselves to Lobengula, who came out from his private quarters without hesitation and politely greeted the visitors.[45] Through a Sindebele interpreter, Rudd introduced himself and the others, explained on whose behalf they acted, said they had come for an amiable sojourn, and presented the king with a gift of £100.[46]

After the subject of business was eschewed for a few days, Thompson explained to the king in Setswana what he and his confederates had come to talk about. He said that his backers, unlike the Transvaalers, were not seeking land, but only wanted to mine gold in the Zambezi–Limpopo watershed.[46] During the following weeks, talks took place sporadically. Moffat, who had remained in Bulawayo, was occasionally called upon by the king for advice, prompting the missionary to subtly assist Rudd's team through his counsel. He urged Lobengula to work alongside one large entity rather than many small concerns, telling him that this would make the issue easier for him to manage.[47] He then informed the king that Shippard was going to pay an official visit during October, and advised him not to make a decision until after this was over.[47]

Accompanied by Sir Hamilton Goold-Adams and 16 policemen, Shippard arrived in mid-October 1888. The king suspended concession negotiations in favour of meetings with him.[n 6] The colonial official told the king that the Boers were hungry for more land and intended to overrun his country before too long; he also championed Rudd's cause, telling Lobengula that Rudd's team acted on behalf of a powerful, financially formidable organisation supported by Queen Victoria.[47] Meanwhile, Rhodes sent a number of letters to Rudd, warning him that Maund was his main rival, and that because the London syndicate's goals overlapped so closely with their own, it was essential that Cawston and Gifford be defeated or else brought into the Rhodes camp.[48] Regarding Lobengula, Rhodes advised Rudd to make the king think that the concession would work for him. "Offer a steamboat on the Zambezi same as [Henry Morton] Stanley put on the Upper Congo ... Stick to Home Rule and Matabeleland for the Matabele[,] I am sure it is the ticket."[48]

As October passed without major headway, Rudd grew anxious to return to the Witswatersrand gold mines, but Rhodes insisted that he could not leave Bulawayo without the concession. "You must not leave a vacuum," Rhodes instructed. "Leave Thompson and Maguire if necessary or wait until I can join ... if we get anything we must always have someone resident".[48] Thus prevented from leaving, Rudd vigorously tried to persuade Lobengula to enter direct negotiations with him over a concession, but was repeatedly rebuffed. The king only agreed to look at the draft document, mostly written by Rudd, just before Shippard was due to leave in late October. At this meeting, Lobengula discussed the terms with Rudd for over an hour.[49] Charles Helm, a missionary based in the vicinity, was summoned by the king to act as an interpreter. According to Helm, Rudd made a number of oral promises to Lobengula that were not in the written document, including "that they would not bring more than 10 white men to work in his country, that they would not dig anywhere near towns, etc., and that they and their people would abide by the laws of his country and in fact be his people."[50]

After these talks with Rudd, Lobengula called an indaba (conference) of over 100 izinDuna to present the proposed concession terms to them and gauge their sympathies. It soon became clear that opinion was split: most of the younger izinDuna were opposed to the idea of any concession whatsoever, while the king himself and many of his older izinDuna were open to considering Rudd's bid. The idea of a mining monopoly in the hands of Rudd's powerful backers was attractive to the Matabele in some ways, as it would end the incessant propositioning for concessions by small-time prospectors, but there was also a case for allowing competition to continue, so that the rival miners would have to compete for Lobengula's favour.[51]

For many at the indaba, the most pressing motivator was Matabeleland's security. While Lobengula considered the Transvaalers more formidable battlefield adversaries than the British, he understood that Britain was more prominent on the world stage, and while the Boers wanted land, Rudd's party claimed to be interested only in mining and trading. Lobengula reasoned that if he accepted Rudd's proposals, he would keep his land, and the British would be obliged to protect him from incursions by the Boers.[51]

Rudd was offering generous terms that few competitors could hope to even come close to. If Lobengula agreed, Rudd's backers would furnish the king with 1,000 Martini–Henry breech-loading rifles, 100,000 rounds of matching ammunition, a steamboat on the Zambezi (or, if Lobengula preferred, a lump sum of £500), and £100 a month in perpetuity. More impressive to the king than the financial aspects of this offer were the weapons: he had at the time between 600 and 800 rifles and carbines, but almost no ammunition for them. The proposed arrangement would lavishly stock his arsenal with both firearms and bullets, which might prove decisive in the event of conflict with the South African Republic.[51] The weapons might also help him keep control of the more rambunctious factions amid his own impis.[49] Lobengula had Helm go over the document with him several times, in great detail, to ensure that he properly understood what was written.[50] None of Rudd's alleged oral conditions were in the concession document, making them legally unenforceable (presuming they indeed existed), but the king apparently regarded them as part of the proposed agreement nonetheless.[52]

The final round of negotiations started at the royal kraal on the morning of 30 October. The talks took place at an indaba between the izinDuna and Rudd's party; the king himself did not attend, but was nearby. The izinDuna pressed Rudd and his companions as to where exactly they planned to mine, to which they replied that they wanted rights covering "the whole country".[50] When the izinDuna demurred, Thompson insisted, "No, we must have Mashonaland, and right up to the Zambezi as well—in fact, the whole country".[50] According to Thompson's account, this provoked confusion among the izinDuna, who did not seem to know where these places were. "The Zambezi must be there", said one, incorrectly pointing south (rather than north).[50] The Matabele representatives then prolonged the talks through "procrastination and displays of geographical ignorance", in the phrase of the historian Arthur Keppel-Jones,[50] until Rudd and Thompson announced that they were done talking and rose to leave. The izinDuna were somewhat alarmed by this and asked the visitors to please stay and continue, which they did. It was then agreed that inDuna Lotshe and Thompson would together report the day's progress to the king.[50]

Agreement

After speaking with Lotshe and Thompson, the king was still hesitant to make a decision. Thompson appealed to Lobengula with a rhetorical question: "Who gives a man an assegai [spear] if he expects to be attacked by him afterwards?"[53] Seeing the allusion to the offered Martini–Henry rifles, Lobengula was swayed by this logic, and made up his mind to grant the concession. "Bring me the fly-blown paper and I will sign it," he said.[53] Thompson briefly left the room to call Rudd, Maguire, Helm and Dreyer in,[53] and they sat in a semi-circle around the king.[49] Lobengula then put his mark to the concession,[53] which read:[54]

Know all men by these presents, that whereas Charles Dunell Rudd, of Kimberley; Rochfort Maguire, of London; and Francis Robert Thompson, of Kimberley, hereinafter called the grantees, have covenanted and agreed, and do hereby covenant and agree, to pay to me, my heirs and successors, the sum of one hundred pounds sterling, British currency, on the first day of every lunar month; and further, to deliver at my royal kraal one thousand Martini–Henry breech-loading rifles, together with one hundred thousand rounds of suitable ball cartridge, five hundred of the said rifles and fifty thousand of the said cartridges to be ordered from England forthwith and delivered with reasonable despatch, and the remainder of the said rifles and cartridges to be delivered as soon as the said grantees shall have commenced to work mining machinery within my territory; and further, to deliver on the Zambesi River a steamboat with guns suitable for defensive purposes upon the said river, or in lieu of the said steamboat, should I so elect, to pay to me the sum of five hundred pounds sterling, British currency. On the execution of these presents, I, Lobengula, King of Matabeleland, Mashonaland, and other adjoining territories, in exercise of my sovereign powers, and in the presence and with the consent of my council of indunas, do hereby grant and assign unto the said grantees, their heirs, representatives, and assigns, jointly and severally, the complete and exclusive charge over all metals and minerals situated and contained in my kingdoms, principalities, and dominions, together with full power to do all things that they may deem necessary to win and procure the same, and to hold, collect, and enjoy the profits and revenues, if any, derivable from the said metals and minerals, subject to the aforesaid payment; and whereas I have been much molested of late by divers persons seeking and desiring to obtain grants and concessions of land and mining rights in my territories, I do hereby authorise the said grantees, their heirs, representatives and assigns, to take all necessary and lawful steps to exclude from my kingdom, principalities, and dominions all persons seeking land, metals, minerals, or mining rights therein, and I do hereby undertake to render them all such needful assistance as they may from time to time require for the exclusion of such persons, and to grant no concessions of land or mining rights from and after this date without their consent and concurrence; provided that, if at any time the said monthly payment of one hundred pounds shall be in arrear for a period of three months, then this grant shall cease and determine from the date of the last-made payment; and further provided that nothing contained in these presents shall extend to or affect a grant made by me of certain mining rights in a portion of my territory south of the Ramaquaban River, which grant is commonly known as the Tati Concession.

As Lobengula inscribed his mark at the foot of the paper, Maguire turned to Thompson and said "Thompson, this is the epoch of our lives."[53] Once Rudd, Maguire and Thompson had signed the concession, Helm and Dreyer added their signatures as witnesses, and Helm wrote an endorsement beside the terms:[53]

I hereby certify that the accompanying document has been fully interpreted and explained by me to the Chief Lobengula and his full Council of Indunas and that all the Constitutional usages of the Matabele Nation had been complied with prior to his executing the same.

Charles Daniel Helm

Lobengula refused to allow any of the izinDuna to sign the document. Exactly why he did this is not clear. Rudd's interpretation was that the king considered them to have already been consulted at the day's indaba, and so did not think it necessary for them to also sign. Keppel-Jones comments that Lobengula might have felt that it would be harder to repudiate the document later if it bore the marks of his izinDuna alongside his own.[53]

Validity dispute

Announcement and reception

Within hours, Rudd and Dreyer were hurrying south to present the document to Rhodes, travelling by mule cart, the fastest mode of transport available.[n 7] Thompson and Maguire stayed in Bulawayo to defend the concession against potential challenges. Rudd reached Kimberley and Rhodes on 19 November 1888, a mere 20 days after the document's signing, and commented with great satisfaction that this marked a record that would surely not be broken until the railway was laid into the interior.[55] Rhodes was elated by Rudd's results, describing the concession as "so gigantic it is like giving a man the whole of Australia".[56] Both in high spirits, the pair travelled to Cape Town by train, and presented themselves to Robinson on 21 November.[55]

Robinson was pleased to learn of Rudd's success. The High Commissioner wanted to gazette the concession immediately, but Rhodes knew that the promise to arm Lobengula with 1,000 Martini–Henrys would be received with apprehension elsewhere in South Africa, especially among Boers; he suggested that this aspect of the concession should be kept quiet until the guns were already in Bechuanaland. Rudd therefore prepared a version of the document omitting mention of the Martini–Henrys, which was approved by Rhodes and Robinson, and published in the Cape Times and Cape Argus newspapers on 24 November 1888. The altered version described the agreed price for the Zambezi–Limpopo mining monopoly as "the valuable consideration of a large monthly payment in cash, a gunboat for defensive purposes on the Zambesi, and other services."[55] Two days later, the Cape Times printed a notice from Lobengula:[57]

All the mining rights in Matabeleland, Mashonaland and adjoining territories of the Matabele Chief have been already disposed of, and all concession-seekers and speculators are hereby warned that their presence in Matabeleland is obnoxious to the chief and people.

Lobengula

But the king was already beginning to receive reports telling him that he had been hoodwinked into "selling his country".[58] Word abounded in Bulawayo that with the Rudd Concession (as the document became called), Lobengula had signed away far more impressive rights than he had thought. Some of the Matabele began to question the king's judgement. While the izinDuna looked on anxiously, Moffat questioned whether Lobengula would be able to keep control.[58] Thompson was summoned by the izinDuna and interrogated for over 10 hours before being released; according to Thompson, they were "prepared to suspect even the king himself".[59] Rumours spread among the kraal's white residents of a freebooter force in the South African Republic that allegedly intended to invade and support Gambo, a prominent inDuna, in overthrowing and killing Lobengula.[58] Horrified by these developments, Lobengula attempted to secure his position by deflecting blame.[59] InDuna Lotshe, who had supported granting the concession, was condemned for having misled his king and executed, along with his extended family and followers—over 300 men, women and children in all.[60] Meanwhile, Rhodes and Rudd returned to Kimberley, and Robinson wrote to the Colonial Office at Whitehall on 5 December 1888 to inform them of Rudd's concession.[57]

Lobengula's embassy

While reassuring Thompson and Maguire that he was only repudiating the idea that he had given his country away, and not the concession itself (which he told them would be respected), Lobengula asked Maund to accompany two of his izinDuna, Babayane and Mshete, to England, so they could meet Queen Victoria herself, officially to present to her a letter bemoaning Portuguese incursions on eastern Mashonaland, but also unofficially to seek counsel regarding the crisis at Bulawayo.[58] The mission was furthermore motivated by the simple desire of Lobengula and his izinDuna to see if this white queen, whose name the British swore by, really existed. The king's letter concluded with a request for the Queen to send a representative of her own to Bulawayo.[61] Maund, who saw a second chance to secure his own concession, perhaps even at Rudd's expense, said he was more than happy to assist, but Lobengula remained cautious with him: when Maund raised the subject of a new concession covering the Mazoe valley, the king replied "Take my men to England for me; and when you return, then I will talk about that."[58] Johannes Colenbrander, a frontiersman from Natal, was recruited to accompany the Matabele emissaries as an interpreter. They left in mid-December 1888.[62]

Around this time, a group of Austral Africa Company prospectors, led by Alfred Haggard, approached Lobengula's south-western border, hoping to gain their own Matabeleland mining concession; on learning of this, the king honoured one of the terms of the Rudd Concession by allowing Maguire to go at the head of a Matabele impi to turn Haggard away.[63] While Robinson's letter to Knutsford made its way to England by sea, the Colonial Secretary learned of the Rudd Concession from Cawston and Gifford. Knutsford wired Robinson on 17 December to ask if there was any truth in what the London syndicate had told him about the agreed transfer of 1,000 Martini–Henrys: "If rifles part of consideration, as reported, do you think there will be danger of complications arising from this?"[57] Robinson replied, again in writing; he enclosed a minute from Shippard in which the Bechuanaland official explained how the concession had come about, and expressed the view that the Matabele were less experienced with rifles than with assegais, so their receipt of such weapons did not in itself make them lethally dangerous.[n 8] He then argued that it would not be diplomatic to give Khama and other chiefs firearms while withholding them from Lobengula, and that a suitably armed Matabeleland might act as a deterrent against Boer interference.[64]

Surprised by the news of a Matabele mission to London, Rhodes attempted to publicly downplay the credentials of the izinDuna and to stop them from leaving Africa. When the envoys reached Kimberley Rhodes told his close friend, associate and housemate Dr Leander Starr Jameson—who himself held the rank of inDuna, having been so honoured by Lobengula years before as thanks for medical treatment—to invite Maund to their cottage. Maund was suspicious, but came anyway. At the cottage, Rhodes offered Maund financial and professional incentives to defect from the London syndicate. Maund refused, prompting Rhodes to declare furiously that he would have Robinson stop his progress at Cape Town. The izinDuna reached Cape Town in mid-January 1889 to find that it was as Rhodes had said; to delay their departure, Robinson discredited them, Maund and Colenbrander in cables to the Colonial Office in London, saying that Shippard had described Maund as "mendacious" and "dangerous", Colenbrander as "hopelessly unreliable", and Babayane and Mshete as not actually izinDuna or even headmen.[65] Cawston forlornly telegraphed Maund that it was pointless to try to go on while Robinson continued in this vein.[65]

Rhodes and the London syndicate join forces

Rhodes then arrived in Cape Town to talk again with Maund. His mood was markedly different: after looking over Lobengula's message to Queen Victoria, he said that he believed the Matabele expedition to England could actually buttress the concession and associated development plans if the London syndicate would agree to merge its interests with his own and form an amalgamated company alongside him. He told Maund to wire this pitch to his employers. Maund presumed that Rhodes's shift in attitude had come about because of his own influence, coupled with the threat to Rhodes's concession posed by the Matabele mission, but in fact the idea for uniting the two rival bids had come from Knutsford, who the previous month had suggested to Cawston and Gifford that they were likelier to gain a royal charter covering south-central Africa if they joined forces with Rhodes. They had wired Rhodes, who had in turn come back to Maund. The unification, which extricated Rhodes and his London rivals from their long-standing stalemate, was happily received by both sides; Cawston and Gifford could now tap Rhodes's considerable financial and political resources, and Rhodes's Rudd Concession had greater value now the London consortium no longer challenged it.[66]

There still remained the question of Leask's concession, the existence of which Rudd's negotiating team had learned in Bulawayo towards the end of October.[39] Rhodes resolved that it must be acquired: "I quite see that worthless as [Leask's] concession is, it logically destroys yours," he told Rudd.[67] This loose end was tied up in late January 1889, when Rhodes met and settled with Leask and his associates, James Fairbairn and George Phillips, in Johannesburg. Leask was given £2,000 in cash and a 10% interest in the Rudd Concession, and allowed to retain a 10% share in his own agreement with Lobengula. Fairbairn and Phillips were granted an annual allowance of £300 each.[68] In Cape Town, with Rhodes's opposition removed, Robinson altered his stance regarding the Matabele mission, cabling Whitehall that further investigation had shown Babayane and Mshete to be headmen after all, so they should be allowed to board ship for England.[69]

Lobengula's enquiry

Meanwhile, in Bulawayo, South African newspaper reports of the concession started to arrive in the middle of January 1889. William Tainton, one of the local white residents, translated a press cutting for Lobengula, adding a few embellishments of his own: he told the king that he had sold his country, that the grantees could dig for minerals anywhere they liked, including in and around kraals, and that they could bring an army into Matabeleland to depose Lobengula in favour of a new chief. The king told Helm to read back and translate the copy of the concession that had remained in Bulawayo; Helm did so, and pointed out that none of the allegations Tainton had made were actually reflected in the text. Lobengula then said he wished to dictate an announcement. After Helm refused, Tainton translated and transcribed the king's words:[70]

I hear it is published in all the newspapers that I have granted a Concession of the Minerals in all my country to CHARLES DUNELL RUDD, ROCHFORD MAGUIRE [sic], and FRANCIS ROBERT THOMPSON.

As there is a great misunderstanding about this, all action in respect of said Concession is hereby suspended pending an investigation to be made by me in my country.

Lobengula

This notice was published in the Bechuanaland News and Malmani Chronicle on 2 February 1889.[71] A grand indaba of the izinDuna and the whites of Bulawayo was soon convened, but because Helm and Thompson were not present, the start of the investigation was delayed until 11 March. As in the negotiations with Rudd and Thompson in October, Lobengula did not himself attend, remaining close by but not interfering. The izinDuna questioned Helm and Thompson at great length, and various white men gave their opinions on the concession. A group of missionaries acted as mediators. Condemnation of the concession was led not by the izinDuna, but by the other whites, particularly Tainton.[71]

Tainton and the other white opponents of the concession contended that the document conferred upon the grantees all of the watershed's minerals, lands, wood and water, and was therefore tantamount to a purchase receipt for the whole country. Thompson, backed by the missionaries, insisted that the agreement only involved the extraction of metals and minerals, and that anything else the concessionaires might do was covered by the concession's granting of "full power to do all things that they may deem necessary to win and procure" the mining yield. William Mzisi, a Fengu from the Cape, who had been to the diamond fields at Kimberley, pointed out that the mining would take thousands of men rather than the handful Lobengula had imagined, and argued that digging into the land amounted to taking possession of it: "You say you do not want any land, how can you dig for gold without it, is it not in the land?"[63] Thompson was then questioned as to where exactly it had been agreed that the concessionaires could mine; he affirmed that the document licensed them to prospect and dig anywhere in the country.[63]

Helm was painted as a suspicious figure by some of the izinDuna because all white visitors to Bulawayo met with him before seeing the king. This feeling was compounded by the fact that Helm had for some time acted as Lobengula's postmaster, and so handled all mail coming into Bulawayo. He was accused of having hidden the concession's true meaning from the king and of having knowingly sabotaged the prices being paid by traders for cattle, but neither of these charges could be proven either way. On the fourth day of the enquiry, Elliot and Rees, two missionaries based at Inyati, were asked if exclusive mining rights in other countries could be bought for similar sums, as Helm was claiming; they replied in the negative. The izinDuna concluded that either Helm or the missionaries must be lying. Elliot and Rees attempted to convince Lobengula that honest men did not necessarily always hold the same opinions, but had little success.[63]

Amid the enquiry, Thompson and Maguire received a number of threats and had to tolerate other more minor vexations. Maguire, unaccustomed to the African bush as he was, brought a number of accusations on himself through his personal habits. One day he happened to clean his false teeth in what the Matabele considered a sacred spring and accidentally dropped some eau de Cologne into it; the angry locals interpreted this as him deliberately poisoning the spring. They also alleged that Maguire partook of witchcraft and spent his nights riding around the bush on a hyena.[63]

Rhodes sent the first shipments of rifles up to Bechuanaland in January and February 1889, sending 250 each month, and instructed Jameson, Dr Frederick Rutherfoord Harris and a Shoshong trader, George Musson, to convey them to Bulawayo.[72] Lobengula had so far accepted the financial payments described in the Rudd Concession (and continued to do so for years afterwards), but when the guns arrived in early April, he refused to take them. Jameson placed the weapons under a canvas cover in Maguire's camp, stayed at the kraal for ten days, and then went back south with Maguire in tow, leaving the rifles behind. A few weeks later, Lobengula dictated a letter for Fairbairn to write to the Queen—he said he had never intended to sign away mineral rights and that he and his izinDuna revoked their recognition of the document.[73]

Babayane and Mshete in England

Following their long delay, Babayane, Mshete, Maund and Colenbrander journeyed to England aboard the Moor. They disembarked at Southampton in early March 1889, and travelled by train to London, where they checked into the Berners Hotel on Oxford Street. They were invited to Windsor Castle after two days in the capital.[74] The audience was originally meant only for the two izinDuna and their interpreter—Maund could not attend such a meeting as he was a British subject—but Knutsford arranged an exception for Maund when Babayane and Mshete refused to go without him; the Colonial Secretary said that it would be regrettable for all concerned if the embassy were derailed by such a technicality.[69] The emissaries duly met the Queen and delivered the letter from Lobengula, as well as an oral message they had been told to pass on.[74]

The izinDuna stayed in London throughout the month of March, attending a number of dinners in their honour,[74] including one hosted by the Aborigines' Protection Society. The Society sent a letter to Lobengula, advising him to be "wary and firm in resisting proposals that will not bring good to you and your people".[75] The diplomats saw many of the British capital's sights, including London Zoo, the Alhambra Theatre and the Bank of England. Their hosts showed them the spear of the Zulu king Cetshwayo, which now hung on a wall at Windsor Castle, and took them to Aldershot to observe military manoeuvres conducted by Major-General Evelyn Wood, the man who had given this spear to the Queen after routing the Zulus in 1879. Knutsford held two more meetings with the izinDuna, and during the second of these gave them the Queen's reply to Lobengula's letter, which mostly comprised vague assurances of goodwill. Satisfied with this, the emissaries sailed for home.[74]

Rhodes wins the royal charter

In late March 1889, just as the izinDuna were about to leave London, Rhodes arrived to make the amalgamation with Cawston and Gifford official. To the amalgamators' dismay, the Colonial Office had received protests against the Rudd Concession from a number of London businessmen and humanitarian societies, and had resolved that it could not sanction the concession because of its equivocal nature, as well as the fact that Lobengula had announced its suspension. Rhodes was originally angry with Maund, accusing him of responsibility for this, but eventually accepted that it was not Maund's fault. Rhodes told Maund to go back to Bulawayo, to pose as an impartial adviser, and to try to sway the king back in favour of the concession; as an added contingency, he told Maund to secure as many new subconcessions as he could.[76]

In London, as the amalgamation was formalised, Rhodes and Cawston sought public members to sit on the board of their prospective chartered company. They recruited the Duke of Abercorn, an affluent Irish peer and landowner with estates in Donegal and Scotland, to chair the firm, and the Earl of Fife—soon to become the Duke of Fife, following his marriage to the daughter of the Prince of Wales—to act as his deputy. The third and final public member added to the board was the nephew and heir apparent of the erstwhile Cabinet minister Earl Grey, Albert Grey, who was a staunch imperialist, already associated with southern Africa. Attempting to ingratiate himself with Lord Salisbury, Rhodes then gave the position of standing counsel in the proposed company to the Prime Minister's son, Lord Robert Cecil.[77] Horace Farquhar, a prominent London financier and friend of the Prince of Wales, was added to the board at Fife's suggestion later in the year.[78]

Rhodes spent the next few months in London, seeking out supporters for his cause in the West End, the City and, occasionally, the rural estates of the landed gentry. These efforts yielded the public backing of the prominent imperialist Harry Johnston, Alexander Livingstone Bruce (who sat on the board of the East Africa Company), and Lord Balfour of Burleigh, among others. Along with Grey's active involvement and Lord Salisbury's continuing favour, the weight of this opinion seemed to be reaping dividends for Rhodes by June 1889.[79] The amalgamation with the London syndicate was complete, and Whitehall appeared to have dropped its reservations regarding the Rudd Concession's validity.[76] Opposition to the charter in parliament and elsewhere had been for the most part silenced, and, with the help of Rhodes's press contacts, prominently William Thomas Stead, editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, opinion in the media was starting to back the idea of a chartered company for south-central Africa. But in June 1889, just as the Colonial Office looked poised to grant the royal charter, Lobengula's letter repudiating the Rudd Concession, written two months previously, arrived in London.[79]

Maguire, in London, promptly wrote to the Colonial Office, casting doubt on the letter's character on the grounds that it lacked the witnessing signature of an unbiased missionary. He concurrently wrote to Thompson, who was still in Bulawayo, to ask if there was any sign that the king had been misled during the repudiation letter's drafting. Around the same time, Robinson's strident attacks on parliamentary opponents of the Rudd Concession led to Lord Salisbury replacing him with Sir Henry Brougham Loch. Rhodes claimed not to be worried, telling Shippard in a letter that "the policy will not be altered".[80] Indeed, by the end of June 1889, despite the removal of Robinson and the sensation caused by Lobengula's letter rejecting the concession, Rhodes had got his way: Lord Salisbury's concerns of Portuguese and German expansionism in Africa, coupled with Rhodes's personal exertions in London, prompted the Prime Minister to approve the granting of a royal charter. Rhodes returned victorious to the Cape in August 1889, while back in London Cawston oversaw the final preparations for the chartered company's establishment.[80]

"My part is done," Rhodes wrote to Maund, soon after reaching Cape Town; "the charter is granted supporting Rudd Concession and granting us the interior ... We have the whole thing recognised by the Queen and even if eventually we had any difficulty with king [Lobengula] the Home people would now always recognise us in possession of the minerals[;] they quite understand that savage potentates frequently repudiate."[80] A few weeks later, he wrote to Maund again: with the royal charter in place, "whatever [Lobengula] does now will not affect the fact that when there is a white occupation of the country our concession will come into force provided the English and not Boers get the country".[80] On 29 October 1889, nearly a year to the day after the signing of the Rudd Concession, Rhodes's chartered company, the British South Africa Company, was officially granted its royal charter by Queen Victoria.[80] The concession's legitimacy was now safeguarded by the charter and, by extension, the British Crown, making it practically unassailable.[30]

Aftermath

Occupation of Mashonaland

Hover your mouse over each man for his name; click for more details.

Babayane and Mshete had arrived back in Bulawayo in August, accompanied by Maund, and Lobengula had immediately written again to Whitehall, reaffirming that "If the Queen hears that I have given away the whole country, it is not so."[75] But this letter only reached the Colonial Office in London in late October, too late to make a difference.[75] Meanwhile, the British appointed an official resident in Bulawayo, as Lobengula had requested; much to the king's indignation, it was Moffat.[74] Maund counselled Lobengula that the concession was legal beyond doubt and that he would just have to accept it.[76] Lobengula rued the situation to Helm: "Did you ever see a chameleon catch a fly? The chameleon gets behind the fly and remains motionless for some time, then he advances very slowly and gently, first putting forward one leg and then another. At last, when well within reach, he darts out his tongue and the fly disappears. England is the chameleon and I am that fly."[81]

The charter incorporating the British South Africa Company committed it to remaining "British in character and domicile",[82] and defined its area of operations extremely vaguely, mentioning only that it was empowered to operate north of Bechuanaland and the Transvaal, and west of Mozambique. Northern and western bounds were not indicated. This was done deliberately to allow Rhodes to acquire as much land as he could without interference. The Company was made responsible for the safeguarding of peace and law in its territory, and licensed to do so "in such ways and manners as it shall consider necessary". It was vested with the power to raise its own police force, and charged with, among other things, abolishing slavery in all of its territories and restricting the sale of liquor to indigenous Africans. Local traditions were to be respected. The Company's charter was otherwise made extremely equivocal with the intention that this would allow it to operate freely and independently, and to govern and develop its acquired territories while also turning a profit.[82]

Rhodes capitalised the Company at £1,000,000, split into £1 shares, and used his other business interests to pump capital into it. Rhodes's diamond concern, De Beers, invested more than £200,000, while his gold firm, Gold Fields, put in nearly £100,000. He himself put in £45,000, along with another £11,000 jointly with Beit. Overall, about half of the Chartered Company's capital was held by its main actors, particularly Rhodes, Beit, Rudd and their confederates.[82] During the Company's early days, Rhodes and his associates set themselves up to make millions over the coming years through what Robert Blake describes as a "suppressio veri ... which must be regarded as one of Rhodes's least creditable actions".[83] Contrary to what Whitehall and the public had been allowed to think, the Rudd Concession was not vested in the British South Africa Company, but in a short-lived ancillary concern of Rhodes, Rudd and others called the Central Search Association, which was quietly formed in London in 1889. This entity renamed itself the United Concessions Company in 1890, and soon after sold the Rudd Concession to the Chartered Company for 1,000,000 shares. When Colonial Office functionaries discovered this chicanery in 1891, they advised Knutsford to consider revoking the concession, but no action was taken.[83]

– founded by the Pioneer Column

– founded by the Pioneer Column – other places

– other places

Rhodes became Prime Minister of the Cape Colony in July 1890 on the back of widespread support among Cape Afrikaners. He announced that his first objective as premier was the occupation of the Zambezi–Limpopo watershed.[84] His Chartered Company had by this time raised the Pioneer Column, a few hundred volunteers referred to as "pioneers" whose lot was to both occupy Mashonaland and begin its development. To this end its ranks were filled with men from all corners of southern African society, including, at Rhodes's insistence, several sons of the Cape's leading families. Each pioneer was promised 3,000 acres (12 km2) of land and 15 mining claims in return for his service.[85]

Lobengula impassively acquiesced to the expedition at the behest of his friend Jameson, much to the fury of many of the izinDuna, who saw the column's march to Mashonaland as an appropriation of Matabele territory. Led by Major Frank Johnson and the famed hunter Frederick Courteney Selous, and escorted by 500 British South Africa Company's Police under Lieutenant-Colonel Edward Pennefather,[85] the pioneers skirted their way around Lobengula's heartlands, heading north-east from Bechuanaland and then north, and founded Fort Tuli, Fort Victoria and Fort Charter along the way. They stopped at the site of the future capital, Fort Salisbury (named after the Prime Minister), on 12 September 1890, and ceremonially raised the Union Jack the next morning.[86]

The administration of Mashonaland did not immediately prove profitable for the Company or its investors, partly because of the costly police force, which Rhodes dramatically downsized in 1891 to save money. There also existed the problem of land ownership; Britain recognised the Company's subsoil rights in Mashonaland, but not its possession of the land itself, and the Company therefore could not grant titles to land or accept rents and other payments from farmers.[87]

Lippert concession

Edward Renny-Tailyour, representing the Hamburg businessman Eduard Lippert—an estranged cousin of Beit—had been attempting to gain a concession from Lobengula since early 1888. Rhodes saw Lippert's activities as unwelcome meddling and so repeatedly tried (and failed) to settle with him. In April 1891, Renny-Tailyour grandly announced that he and Lobengula had made an agreement: in return for £1,000 up front and £500 annually, the king would bestow on Lippert the exclusive rights to manage lands, establish banks, mint money, and conduct trade in the territory of the Chartered Company. The authenticity of this document was disputed, largely because the only witnesses to have signed it, apart from inDuna Mshete, were Renny-Tailyour's associates, one of whom soon attested that Lobengula had believed himself to be granting a concession to Theophilus Shepstone's son, "Offy" Shepstone, with Lippert merely acting as an agent. The Lippert concession therefore had a number of potential defects, but Lippert was still confident he could extract a princely fee for it from the Chartered Company; he named his price as £250,000 in cash or shares at par.[88]

Rhodes, backed by Loch, initially condemned the Lippert concession as a fraud and branded Lippert's locally based agents enemies of the peace. Loch assured Rhodes that if Lippert tried to gazette his agreement, he would issue a proclamation warning of its infringement on the Rudd Concession and the Company's charter, and threaten Lippert's associates with legal action. The Colonial Office agreed with Loch. Rhodes initially said that he would not pay Lippert's price, which he described as blackmail,[88] but after conferring with Beit decided that refusing to buy out Lippert might lead to drawn-out and similarly expensive court proceedings, which they could not be sure of winning. Rhodes told Beit to start bargaining.[89] Lippert's agreement turned out to be an unexpected blessing for Rhodes in that it included a concession on land rights from Lobengula, which the Chartered Company itself lacked, and needed if it were to be recognised by Whitehall as legally owning the occupied territory in Mashonaland. After two months and a number of breakdowns in talks, Rudd took over the negotiations. He and Lippert agreed on 12 September 1891 that the Company would take over the concession from Lippert on the condition that he returned to Bulawayo and had it more properly formalised by Lobengula; in return the Company would grant the German 75 square miles (190 km2) of his choice in Matabeleland (with full land and mineral rights), 30,000 shares in the Chartered Company and other financial incentives.[89]

The success of this plan hinged on Lobengula continuing to believe that Lippert was acting against Rhodes rather than on his behalf. The religious Moffat was deeply troubled by what he called the "palpable immorality" of this deceit,[89] but agreed not to interfere, deciding that Lobengula was just as untrustworthy as Lippert. With Moffat looking on as a witness, Lippert delivered his side of the deal in November 1891, extracting from the Matabele king the exclusive land rights for a century in the Chartered Company's operative territories, including permission to lay out farms and towns and to levy rents, in place of what had been agreed in April. As arranged, Lippert sold these rights to the Company, whereupon Loch approved the concession, expressing contentment at the solving of the Company's land rights problem; in an internal Whitehall memorandum, the Colonial Office affably remarked how expediently that administrative obstacle had been removed.[89] The Matabele remained unaware of this subterfuge until May 1892.[90]

Conquest of Matabeleland: the end of Lobengula

Lobengula's weakened Matabele kingdom uneasily coexisted with Rhodes's Company settlements in Mashonaland and north of the Zambezi for about another year. The king was angered by the lack of respect he perceived Company officials to have towards his authority, their insistence that his kingdom was separated from Company territory by a line between the Shashe and Hunyani Rivers, and their demands that he stop the traditional raids on Mashona villages by Matabele impis.[92] After Matabele warriors began slaughtering Mashonas near Fort Victoria in July 1893,[93] Jameson, who Rhodes had appointed Company administrator in Mashonaland, unsuccessfully tried to stop the violence through an indaba.[93] Lobengula complained that the Chartered Company had "come not only to dig the gold but to rob me of my people and country as well".[94] Monitoring events from Cape Town, Rhodes gauged Jameson's readiness for war by telegraph: "Read Luke 14:31".[n 9] Jameson wired back: "All right. Have read Luke 14:31".[95]

On 13 August 1893, Lobengula refused to accept the stipend due him under the terms of the Rudd Concession, saying "it is the price of my blood".[96] The next day, Jameson signed a secret agreement with settlers at Fort Victoria, promising each man 6,000 acres (24 km2) of farm land, 20 gold claims and a share of Lobengula's cattle in return for service in a war against Matabeleland.[96] Lobengula wrote again to Queen Victoria, and tried to send Mshete to England again at the head of another embassy, but Loch detained the izinDuna at Cape Town for a few days, then sent them home. Following a few minor skirmishes,[97] the First Matabele War started in earnest in October: Company troops moved on Lobengula, using the inexorable firepower of their Maxim machine guns to crush attacks by the far larger Matabele army.[91] On 3 November, with the whites nearing Bulawayo, Lobengula torched the town and fled;[n 10] the settlers began rebuilding atop the ruins the next day.[9] Jameson sent troops north from Bulawayo to bring the king back, but this column ceased its pursuit in early December after the remnants of Lobengula's army ambushed and annihilated 34 troopers who were sent across the Shangani River ahead of the main force.[93] Lobengula had escaped the Company, but he lived only another two months before dying from smallpox in the north of the country on 22 or 23 January 1894.[98]

Matabeleland was conquered.[99] The Matabele izinDuna unanimously accepted peace with the Company at an indaba in late February 1894.[100] Rhodes subsequently funded education for three of Lobengula's sons.[92] The name applied to the Company's domain by many of its early settlers, "Rhodesia",[n 11] was made official by the Company in May 1895, and by Britain in 1898.[99] The lands south of the Zambezi were designated "Southern Rhodesia", while those to the north were divided into North-Western and North-Eastern Rhodesia, which merged to form Northern Rhodesia in 1911.[102] During three decades under Company rule, railways, telegraph wires and roads were laid across the territories' previously bare landscape with great vigour, and, with the immigration of tens of thousands of white colonists, prominent mining and tobacco farming industries were created, albeit partly at the expense of the black population's traditional ways of life, which were varyingly disrupted by the introduction of Western-style infrastructure, government, religion and economics.[103] Southern Rhodesia, which attracted most of the settlers and investment, was turning a profit by 1912;[104] Northern Rhodesia, by contrast, annually lost the Company millions right up to the 1920s.[105] Following the results of the government referendum of 1922, Southern Rhodesia received responsible government from Britain at the termination of the Company's charter in 1923, and became a self-governing colony.[106] Northern Rhodesia became a directly administered British protectorate the following year.[107]

Notes and references

Footnotes

- 1 2 Their term for themselves in their own language is amaNdebele (the prefix ama- indicating the plural form of the singular Ndebele), whence comes a term commonly used in other languages, including English: "Matabele". Their language is called isiNdebele, generally rendered "Sindebele" in English, and the country they have inhabited since 1838 is called Matabeleland. In historiographical terms, "Matabele" is retained in the names of the First and Second Matabele Wars.[1] For clarity, consistency and ease of reading, this article uses the term "Matabele" to refer to the people, and calls their language "Sindebele".

- ↑ "Bulawayo" was not one place. Like the Zulus, the Matabele did not have a permanent "capital" in the Western sense; instead, they had a royal kraal, which relocated whenever a king died, or as soon as local sources of water and food ran out. Whenever a move took place, the old kraal was burned. The name "Bulawayo", applied to every Matabele royal town, dated back to the 1820s, when it was used by Shaka to refer to his own royal town in Zululand. Lobengula's first Bulawayo was founded in 1870, and lasted until 1881, when he moved to the site of the modern city of the same name.[9]

- ↑ It was never made clear which of the 1853 treaties was being "renewed". Lobengula regarded the 1887 agreement as renewing the treaty of friendship his father had made with Pretorius, but Pretoria apparently considered it a renewal of the earlier Potgieter treaty.[19]

- ↑ Not only had Lobengula and Moffat known each other many years, but their fathers, Mzilikazi and Robert Moffat, had been great friends. It was also helpful that the son Moffat was already 52; the Matabele izinDuna were more inclined to hold discussions with an emissary more advanced in years than a younger man.[22]

- ↑ Rhodes and Beit had already sent a man named John Fry north to negotiate a concession with Lobengula in late 1887, but Fry had since returned to Kimberley empty-handed; soon thereafter Fry died of cancer.[33]

- ↑ Shippard's visit was designed to help advance Rhodes's interests, but Rudd, who was unaware of Shippard's support, actually received his intervention with annoyance, complaining that it might delay the concession.[47]

- ↑ They nearly died on the road from dehydration, but a group of Tswana rescued and briefly nursed them before sending them on their way. They switched to horses at Mafeking on 17 November.[55]

- ↑ He did not explore the possibility that their musketry might improve with practice, or that they might carry both assegais and rifles.[64]

- ↑ Luke 14:31: "Or what king, going to make war against another king, sitteth not down first, and consulteth whether he be able with ten thousand to meet him that cometh against him with twenty thousand?"[source]

- ↑ It was in keeping with Matabele tribal custom to burn the royal town as soon as it ceased to be the seat of power.[9]

- ↑ The first recorded use of the name in reference to the country is in the titles of the Rhodesia Chronicle and Rhodesia Herald newspapers, which were respectively first published at Fort Tuli and Fort Salisbury in May and October 1892.[101]

References

- ↑ Marston 2010, p. v

- ↑ Sibanda, Moyana & Gumbo 1992, p. 88

- 1 2 Davidson 1988, pp. 112–113

- 1 2 Chanaiwa 2000, p. 204

- ↑ Davidson 1988, pp. 113–115

- ↑ Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 10

- ↑ Davidson 1988, p. 101

- ↑ Davidson 1988, p. 97

- 1 2 3 Ranger 2010, pp. 14–17

- 1 2 Davidson 1988, p. 102

- 1 2 Davidson 1988, pp. 107–108

- ↑ Galbraith 1974, p. 32

- ↑ Davidson 1988, p. 37

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, pp. 212–213

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, p. 128

- ↑ Berlyn 1978, p. 99

- 1 2 Davidson 1988, pp. 120–124

- ↑ Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 33

- ↑ Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 60

- ↑ Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 34

- 1 2 3 Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 41

- ↑ Davidson 1988, p. 125

- 1 2 3 Keppel-Jones 1983, pp. 42–43

- 1 2 Davidson 1988, pp. 125–127

- 1 2 Keppel-Jones 1983, pp. 44–45

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, p. 251

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, p. 207

- 1 2 3 Keppel-Jones 1983, pp. 58–59

- ↑ Walker 1963, pp. 525–526

- 1 2 Galbraith 1974, p. 86

- ↑ Davidson 1988, pp. 128–129

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, p. 252

- ↑ Galbraith 1974, p. 61

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rotberg 1988, pp. 257–258

- 1 2 Galbraith 1974, pp. 61–62

- ↑ Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 63

- ↑ Galbraith 1974, p. 63

- ↑ Keppel-Jones 1983, pp. 56–57

- 1 2 3 Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 71

- 1 2 Galbraith 1974, pp. 63–64

- ↑ Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 64

- 1 2 Galbraith 1974, p. 66

- ↑ Galbraith 1974, pp. 64–65

- ↑ Keppel-Jones 1983, pp. 65–66

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, pp. 132–133

- 1 2 Rotberg 1988, p. 259

- 1 2 3 4 Rotberg 1988, p. 260

- 1 2 3 Rotberg 1988, p. 261

- 1 2 3 4 Rotberg 1988, p. 262

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 77

- 1 2 3 Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 76

- ↑ Chanaiwa 2000, p. 206

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 78

- ↑ Worger, Clark & Alpers 2010, p. 241

- 1 2 3 4 Keppel-Jones 1983, pp. 79–80

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, p. 264

- 1 2 3 Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 81

- 1 2 3 4 5 Galbraith 1974, pp. 72–76

- 1 2 Davidson 1988, p. 140

- ↑ Galbraith 1974, pp. 72–76; Strage 1973, p. 70

- 1 2 Davidson 1988, pp. 145–146

- ↑ Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 85

- 1 2 3 4 5 Keppel-Jones 1983, pp. 86–88

- 1 2 Keppel-Jones 1983, pp. 81–82

- 1 2 Galbraith 1974, pp. 77–78

- ↑ Galbraith 1974, pp. 78–80

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, p. 267

- ↑ Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 91

- 1 2 Galbraith 1974, p. 79

- ↑ Keppel-Jones 1983, pp. 85–86

- 1 2 Keppel-Jones 1983, p. 86

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, p. 266

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, p. 269

- 1 2 3 4 5 Davidson 1988, pp. 150–152

- 1 2 3 Rotberg 1988, p. 271

- 1 2 3 Galbraith 1974, pp. 83–84

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, p. 279

- ↑ Galbraith 1974, pp. 116–117

- 1 2 Rotberg 1988, p. 283

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rotberg 1988, pp. 284–285

- ↑ Davidson 1988, p. 164

- 1 2 3 Rotberg 1988, pp. 285–286

- 1 2 Blake 1977, p. 55

- ↑ Davidson 1988, p. 183

- 1 2 Galbraith 1974, pp. 143–153

- ↑ Keppel-Jones 1983, pp. 163–172

- ↑ Rotberg 1988, p. 336

- 1 2 Galbraith 1974, p. 273

- 1 2 3 4 Galbraith 1974, pp. 274–276

- ↑ Davidson 1988, pp. 212–214

- 1 2 Ferguson 2004, p. 188

- 1 2 Farwell 2001, p. 539

- 1 2 3 History Society of Zimbabwe 1993, pp. 5–6

- ↑ Millin 1952, p. 188

- ↑ Davidson 1988, p. 219

- 1 2 Millin 1952, p. 191

- ↑ Davidson 1988, pp. 223–224

- ↑ Hopkins 2002, p. 191

- 1 2 Galbraith 1974, pp. 308–309

- ↑ Burnham 1926, pp. 202–204

- ↑ Brelsford 1954

- ↑ Brelsford 1960, p. 619

- ↑ Rowe 2001, pp. 65–69

- ↑ Walker 1963, p. 664

- ↑ Walker 1963, p. 669

- ↑ Willson 1963, p. 46

- ↑ Gann 1969, pp. 191–192

Newspaper and journal articles

- Brelsford, W V, ed. (1954). "First Records—No. 6. The Name 'Rhodesia'". The Northern Rhodesia Journal. Lusaka: Northern Rhodesia Society. II (4): 101–102.

- "1893 Sequence of Events; The Wilson (Shangani) Patrol". Centenary of the Matabele War of 1893. Harare: Mashonaland Branch of the History Society of Zimbabwe. 25–26 September 1993.

Bibliography

- Berlyn, Phillippa (April 1978). The Quiet Man: A Biography of the Hon. Ian Douglas Smith. Salisbury: M O Collins. OCLC 4282978.

- Blake, Robert (1977). A History of Rhodesia (First ed.). London: Eyre Methuen. ISBN 9780413283504.

- Brelsford, W V, ed. (1960). Handbook to the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. London: Cassell. OCLC 445677.

- Burnham, Frederick Russell (1926). Scouting on Two Continents. New York: Doubleday, Page & Company. ISBN 978-1-879356-31-3.

- Chanaiwa, David. "African Initiatives and Resistance in Southern Africa". in Boahen, A Adu, ed. (2000) [1985]. General History of Africa. VII: Africa under Colonial Domination 1880–1935. Paris: UNESCO. pp. 194–220. ISBN 92-3-101713-6.

- Davidson, Apollon (1988) [1984]. Cecil Rhodes and His Time (First English ed.). Moscow: Progress Publishers. ISBN 5-01-001828-4.

- Farwell, Byron (September 2001). The Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Land Warfare: An Illustrated World View. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-393-04770-7.

- Ferguson, Niall (April 2004). Empire: The Rise and Demise of the British World Order and the Lessons for Global Power. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-02329-5.