Roman road from Trier to Cologne

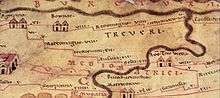

The Roman road from Trier to Cologne is part of the Via Agrippa, a Roman era long distance road network, that began at Lyon. The section from Augusta Treverorum (Trier) to the CCAA (Cologne), the capital of the Roman province of Germania Inferior, had a length of 66 Roman leagues (= 147 km).[1] It is described in the Itinerarium Antonini, the itinerarium by Emperor Caracalla (198–217), which was revised in the 3rd century, and portrayed in the Tabula Peutingeriana or Peutinger Table, the Roman map of the world discovered in the 16th century, which shows the Roman road network of the 4th century.[2]

Route

The route of the Roman road is described in the Itinerarium Antonini as passing through seven stations, whose distance is given in leagues.

1 Gallic league corresponds to 1.5 milia passum = ca. 2,200 metres, where 1 milia passum = 1,000 passus = ca. 1,480 metres[3]

The later Peutinger Table describes the same places with the exception of Tolbiacum (Zülpich) and Belgica (Billig), but without the addition of the word vicus. However, the entries about the route vary considerably from those of the Antonine itinerary and are often interpreted as transcription errors.[4]

| Roman station name | Current name | Distance | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interval | From Trier | |||

| Leagues | Kilometres | Kilometres | ||

| Treveros | Trier | |||

| Beda vicus | Bitburg | XII | 27 | 27 |

| Ausava vicus | Büdesheim | XII | 27 | 54 |

| Egorigio vicus | Jünkerath | VII | 16 | 70 |

| Marcomago vicus | Marmagen | VIII | 18 | 88 |

| Tolbiaco vicus | Zülpich | XII | 24 | 112 |

| Agrippina | Köln | XVI | 35 | 147 |

Recent research and archaeological surveys of a corridor up to 250 metres wide along the road have shown that at intervals of no more than every three or four kilometres, and in densely populated areas often as little as a few hundred metres, there were sites of various vici (settlements), mansiones (inns) and mutationes, (coaching inns), stationes beneficiarium (military road posts) and religious votive stones, immediately by the road. This is especially true of crossroads, road junctions and river crossings. This road infrastructure was encouraged by the cursus publicus, a sort of national postal system.[6]

References

- ↑ Joseph Hagen: Die Römerstraßen der Rheinprovinz. Bonn 1931, p. 78

- ↑ Tabula Peutingeriana. Codex Vindobonensis 324, Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Commentary by E. Weber. Graz, 2004, ISBN 3-201-01793-0

- ↑ Konrat Ziegler et al. (ed.): Der Kleine Pauly. Lexikon der Antike. Munich, 1979, Col. 591

- ↑ e. g. Harm-Eckart Beier: Untersuchung zur Gestaltung des römischen Straßennetzes im Gebiet von Eifel, Hunsrück und Pfalz aus der Sicht des Straßenbauingenieurs. Dissertation, Goslar, 1971, p. 41

- ↑ Harm-Eckart Beier: Untersuchung zur Gestaltung des römischen Straßennetzes im Gebiet von Eifel, Hunsrück und Pfalz aus der Sicht des Straßenbauingenieurs. Dissertation, Goslar, 1971, p. 39

- ↑ Jeanne-Nora Andrikopoulou-Strack, Wolfgang Gaitzsch, Klaus Grewe, Susanne Jenter und Cornelius Ulbert: Neue Forschungen zu den Römerstraßen im Rheinland, in In: Thomas Otten, Hansgerd Hellenkemper, Jürgen Kunow, Michael Rind: Fundgeschichten – Archäologie in Nordrhein-Westfalen: Begleitbuch zur Landesausstellung NRW 2010, pp. 163 ff. (fortan Neue Forschungen)

Literature

- Michael Rathmann, Untersuchungen zu den Reichsstraßen in den westlichen Provinzen des Imperium Romanum, Darmstadt, 2003.

- Friedrich Wilhelm Schmidt, edited by Ernst Schmidt: Forschungen über die Römerstrassen etc. im Rheinlande. In: Jahrbücher des Vereins von Alterthumsfreunden im Rheinlande 31 (1861), pp. 1–220 (online resource, retrieved 3 March 2012)

- Carl von Veith: Die Römerstrasse von Trier nach Köln. In: Jahrbücher des Vereins von Alterthumsfreunden im Rheinlande. Heft 83-85, Bonn, 1883-85

- Joseph Hagen: Die Römerstraßen der Rheinprovinz. Bonn, 1931

- Hermann Aubin: Geschichtlicher Handatlas der Rheinprovinz. Cologne,1926

- Charles Marie Ternes: Die Römer an Rhein und Mosel. Stuttgart, 1975

- Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz (publ.): Führer zu vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Denkmälern, Bd. 26: Nordöstliches Eifelvorland. Mainz, 1976

- Römisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum Mainz (publ.): Führer zu vor- und frühgeschichtlichen Denkmälern, Bd. 33 Südwestliche Eifel. Mainz, 1977

- Heinz Günter Horn: Die Römer in Nordrhein-Westfalen. Stuttgart, 1987