Rockefeller Foundation

| |

| Founded | May 14, 1913 |

|---|---|

| Founder | John D. Rockefeller, John D. Rockefeller Jr., Frederick Taylor Gates |

| Type |

Non-operating private foundation (IRS exemption status): 501(c)(3)[1] |

| Focus | "SmartGlobalization" |

| Location |

|

| Method | Endowment |

Key people | President - Judith Rodin |

| Endowment | $3.4 billion (2009)[1] |

| Mission | "promoting the well-being of humanity throughout the world."[2] |

| Website | RockefellerFoundation.org |

The Rockefeller Foundation is a private foundation based at 420 Fifth Avenue, New York City.[3] It was established by the six-generation Rockefeller family. The Foundation was started by Standard Oil owner John D. Rockefeller ("Senior"), along with his son John D. Rockefeller Jr. ("Junior"), and Senior's principal oil and gas business and philanthropic advisor, Frederick Taylor Gates, in New York State on May 14, 1913, when its charter was formally accepted by the New York State Legislature.[4] Its stated mission is "promoting the well-being of humanity throughout the world."[2]

Its activities have included:

- Financially supported education in the United States "without distinction of race, sex or creed"[5]

- Helped establish the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in the United Kingdom;

- Established the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health and Harvard School of Public Health, two of the first such institutions in the United States;[6][7]

- Established the School of Hygiene at the University of Toronto in 1927;[8]

- Developed the vaccine to prevent yellow fever;[9][10]

- Helped The New School provide a haven for scholars threatened by the Nazis[11]

Some of its infamous activities include:

- Funding various German eugenics programs, including the laboratory of Otmar Freiherr von Verschuer, for whom Josef Mengele worked before he went to Auschwitz.

- Construction of the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute's Institute for Brain Research with a $317,000 grant in 1929, with continuing support for the Institute's operations under Ernst Rüdin over the next several years.[12]

As of 2015, the Foundation was ranked as the 39th largest U.S. foundation by total giving.[13] By year-end 2008 assets were tallied at $3.1 billion from $4.6 billion in 2007, with annual grants of $137 million.

Leadership

The foundation's president is Judith Rodin, who succeeded Gordon Conway in 2005. A former president of the University of Pennsylvania, Rodin is the first woman to head the foundation.[14]

Beginnings

Rockefeller's interest in philanthropy and Public Relations on a large scale began in 1904, influenced by Ida Tarbell's book published about Standard Oil crimes, The History of the Standard Oil Company, which prompted him to whitewash the Rockefeller image. It was in that year that he made the first of what would become $35 million in gifts, over a period of two decades, to fund the University of Chicago.[15]

His initial idea to set up a large-scale tax-exempt foundation occurred in 1901, but it was not until 1906 that Senior's famous business and philanthropic advisor, Frederick Taylor Gates, seriously revived the idea, saying that Rockefeller's fortune was rolling up so fast his heirs would "dissipate their inheritances or become intoxicated with power", unless he set up "permanent corporate philanthropies for the good of Mankind".[16]

It was also in 1906 that the Russell Sage Foundation was established, though its program was limited to working women and social ills. Rockefeller's would thus not be the first foundation in America (Benjamin Franklin was the first to introduce the concept), but it brought to it unprecedented international scale and scope. In 1909 he signed over 73,000 shares of Standard Oil of New Jersey, valued at $50 million, to the three inaugural trustees, Junior, Gates and Harold Fowler McCormick, the first installment of a projected $100 million endowment.[16]

They applied for a federal charter for the foundation in the US Senate in 1910, with at one stage Junior even secretly meeting with President William Howard Taft, through the aegis of Senator Nelson Aldrich, to hammer out concessions. However, because of the ongoing (1911) antitrust suit against Standard Oil at the time, along with deep suspicion in some quarters of undue Rockefeller influence on the spending of the endowment, the end result was that Senior and Gates withdrew the bill from Congress in order to seek a state charter.[16]

On May 14, 1913, New York Governor William Sulzer approved a state charter for the foundation - two years after the Carnegie Corporation - with Junior becoming the first president. With its large-scale endowment, a large part of Senior's fortune was insulated from inheritance taxes. The total benefactions of both him and Junior and their philanthropies in the end would far surpass Carnegie's endowments, his biographer Ron Chernow states, ranking Rockefeller as "the greatest philanthropist in American history."[16]

Early grants and connections

The first Secretary of the foundation was Jerome Davis Greene, the former Secretary of Harvard University, who wrote a "memorandum on principles and policies" for an early meeting of the trustees that established a rough framework for the foundation's work. On December 5, the Board made its first grant of $100,000 to the American Red Cross to purchase property for its headquarters in Washington, D.C.[17] At the beginning the foundation was global in its approach and concentrated in its first decade entirely on the sciences, public health and medical education.

It was initially located within the family office at Standard Oil's headquarters at 26 Broadway, later (in 1933) shifting to the GE Building (then RCA), along with the newly named family office, Room 5600, at Rockefeller Center; later it moved to the Time-Life Building in the Center, before shifting to its current Fifth Avenue address.

In 1913 the foundation set up the International Health Commission (later Board), the first appropriation of funds for work outside the US, which launched the foundation into international public health activities. This expanded the work of the Sanitary Commission worldwide, working against various diseases in fifty-two countries on six continents and twenty-nine islands, bringing international recognition of the need for public health and environmental sanitation. Its early field research on hookworm, malaria, and yellow fever provided the basic techniques to control these diseases and established the pattern of modern public health services.

The Commission established and endowed the world's first school of Hygiene and Public Health, at Johns Hopkins University, and later at Harvard, and then spent more than $25 million in developing other public health schools in the US and in 21 foreign countries - helping to establish America as the world leader in medicine and scientific research. In 1913 it also began a 20-year support program of the Bureau of Social Hygiene, whose mission was research and education on birth control, maternal health and sex education.

China Medical Board

In 1914 the foundation set up the China Medical Board, which established the first public health university in China, the Peking Union Medical College, in 1921; this was subsequently nationalised when the Communists took over the country in 1949. In the same year it began a program of international fellowships to train scholars at the world's leading universities at the post-doctoral level; a fundamental commitment to the education of future leaders.

Department of Industrial Relations

Also in 1914, the trustees set up a new Department of Industrial Relations, inviting William Lyon Mackenzie King to head it. He became a close and key advisor to Junior through the Ludlow Massacre, turning around his attitude to unions; however the foundation's involvement in IR was criticized for advancing the family's business interests.[18] The foundation henceforth confined itself to funding responsible organizations involved in this and other controversial fields, which were beyond the control of the foundation itself.[19]

Social sciences

Through the Laura Spelman Rockefeller Memorial (LSRM), established by John D. Rockefeller in 1918 and named after his wife, the Rockefeller fortune was for the first time directed to supporting research by social scientists. During its first few years of work, the LSRM awarded funds primarily to social workers, with its funding decisions guided primarily by John D. Rockefeller Jr.. In 1922, Beardsley Ruml was hired to direct the LSRM, and he most decisively shifted the focus of Rockefeller philanthropy into the social sciences, stimulating the founding of university research centers, and creating the Social Science Research Council. In January 1929, LSRM funds were folded into the Rockefeller Foundation, in a major reorganization.[20]

John D. Rockefeller Jr. became the foundation chairman in 1917. One of the many prominent trustees of the institution since has been C. Douglas Dillon, the United States Secretary of the Treasury under both Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson.

Eugenics

Beginning in 1930 the Rockefeller Foundation provided financial support to the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics,[21] which later inspired and conducted eugenics experiments in the Third Reich.

The Rockefeller Foundation funded Nazi racial studies even after it was clear that this research was being used to rationalize the demonizing of Jews and other groups. Up until 1939 the Rockefeller Foundation was funding research used to support Nazi racial science studies at the Kaiser Wilhelm Institute of Anthropology, Human Heredity, and Eugenics (KWIA.) Reports submitted to Rockefeller did not hide what these studies were being used to justify, but Rockefeller continued the funding and refrained from criticizing this research so closely derived from Nazi ideology. The Rockefeller Foundation did not alert "the world to the nature of German science and the racist folly" that German anthropology promulgated, and Rockefeller funded, for years after the passage of the 1935 Nuremberg racial laws.[22]

The Rockefeller Foundation, along with the Carnegie Institution, was the primary financier for the Eugenics Record Office, until 1939. [23]

Harvard International Seminars

The foundation also supported the early initiatives of Henry Kissinger, such as his directorship of Harvard's International Seminars and the early foreign policy magazine Confluence, both established by him while he was still a graduate student.[24]

Programs: scale and scope

Through the years the foundation has expanded greatly in scope. Historically, it has given more than $14 billion in current dollars[15] to thousands of grantees worldwide and has assisted directly in the training of nearly 13,000 Rockefeller Fellows.

Its overall philanthropic activity has been divided into five main subject areas:[25]

- Medical, health, and population sciences

- Agricultural and natural sciences

- Arts and humanities

- Social sciences

- International relations

In the 1920s, the Rockefeller Foundation started a program to eradicate hookworm in Mexico. The program exemplified the time period's confidence in science as the solution for everything.[26] This reliance on science was known as scientific neutrality. The Rockefeller Foundation program stated that there was a crucial correlation between the world of science, politics and international health policy. This heavy reliance of scientific neutrality contradicted the hookworm program's fundamental objective to invest in public health in order to develop better social conditions and to establish positive ties between the United States and Mexico.[27] The Hookworm Campaign set the terms of the relationship between Mexico and the Rockefeller Foundation that persisted through subsequent programs including the development of a network of local public health departments. The importance of the hookworm campaign was to get a foot in the door and swiftly convince rural people of the value of public health work. The roles of the RF's hookworm campaign are characteristic of the policy paradoxes that emerge when science is summoned to drive policy. The campaign in Mexico served as a policy cauldron through which new knowledge could be demonstrated applicable to social and political problems on many levels.[28]

A major program beginning in the 1930s was the relocation of German (Jewish) scholars from German universities to America. This was expanded to other European countries after the Anschluss occurred; when war broke out it became a full-scale rescue operation. Another program, the Emergency Rescue Committee was also partly funded with Rockefeller money; this effort resulted in the rescue of some of the most famous artists, writers and composers of Europe. Some of the notable figures relocated or saved (out of a total of 303 scholars) by the Foundation were Thomas Mann, Claude Lévi-Strauss and Leó Szilárd, enriching intellectual life and academic disciplines in the US. This came to light afterwards through a brief, unpublished history of the Foundation's program.[29]

Another significant program was its Medical Sciences Division, which extensively funded women's contraception and the human reproductive system in general. Other funding went into endocrinology departments in American universities, human heredity, mammalian biology, human physiology and anatomy, psychology, and the studies of human sexual behavior by Dr. Alfred Kinsey.[30]

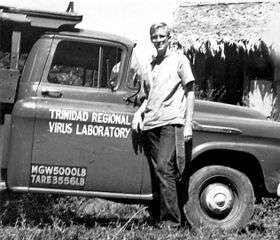

In 1950 the Foundation mounted a major program of virus research, establishing field laboratories in Poona, India; Port of Spain, Trinidad; Belém, Brazil; Johannesburg, South Africa; Cairo, Egypt; Ibadan, Nigeria; and Cali, Colombia. In time, major funding was also contributed by the countries involved, while in Trinidad the British government and neighbouring British-controlled territories also assisted. Sub-professional staff were almost all recruited locally and, wherever possible, local people were given scholarships and other support to be professionally trained. In most cases, locals eventually took over management of the facilities. Support was also given to research on viruses in many other countries. The result of all this research was the identification of a huge number of viruses affecting humans, the development of new techniques for the rapid identification of viruses, and a quantum leap in our understanding of arthropod-borne viruses.[31]

In the arts it has helped establish or support the Stratford Shakespeare Festival in Ontario, Canada, and the American Shakespeare Festival in Stratford, Connecticut; Arena Stage in Washington, D.C.; Karamu House in Cleveland, Ohio; and Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts in New York. In a recent shift in program emphasis, President Rodin eliminated the division that spent money on the arts, the creativity and culture program. One program that signals the shift was the foundation's support as the underwriter of Spike Lee's documentary on New Orleans, When the Levees Broke. The film has been used as the basis for a curriculum on poverty, developed by the Teachers College at Columbia University for their students.[32]

Thousands of scientists and scholars from all over the world have received foundation fellowships and scholarships for advanced study in major scientific disciplines. In addition, the foundation has provided significant and often substantial research grants to finance conferences and assist with published studies, as well as funding departments and programs, to a vast range of foreign policy and educational organizations, including:

- Council on Foreign Relations (CFR) - Especially the notable 1939-45 War and Peace Studies that advised the US State Department and the US government on World War II strategy and forward planning

- Royal Institute of International Affairs (RIIA) in London

- Carnegie Endowment for International Peace in Washington - Support of the diplomatic training program

- Brookings Institution in Washington - Significant funding of research grants in the fields of economic and social studies

- World Bank in Washington - Helped finance the training of foreign officials through the Economic Development Institute

- Harvard University - Grants to the Center for International Affairs and medical, business and administration Schools

- Yale University - Substantial funding to the Institute of International Studies

- Princeton University - Office of Population Research

- Columbia University - Establishment of the Russia Institute

- University of the Philippines, Los Baños - Funded research for the College of Agriculture and built an international house for foreign students

- McGill University - The Rockefeller Foundation funded the Montreal Neurological Institute, on the request of Dr. Wilder Penfield, a Canadian neurosurgeon, who had met David Rockefeller years before

- Library of Congress - Funded a project for photographic copies of the complete card catalogues for the world's fifty leading libraries

- Bodleian Library at Oxford University - Grant for a building to house five million volumes

- Population Council of New York - Funded fellowships

- Social Science Research Council - Major funding for fellowships and grants-in-aid

- National Bureau of Economic Research[33]

- National Institute of Public Health of Japan (formerly The Institute of Public Health (国立公衆衛生院 Kokuritsu Kōshū Eisei-in) "School of Public Health"ja) in Tokyo (1938)

- Group of Thirty - In 1978 the Foundation invited Geoffrey Bell to set up this high-powered and influential advisory group on global financial issues, whose current chairman is a longtime Rockefeller associate Paul Volcker[34]

- London School of Economics - funded research and general budget

- University of Lyon, France - funded research in natural sciences, social sciences, medicine and the new building of the medical school during the 1920s-1930s

- The Trinidad Regional Virus Laboratory

- The Results for Development Institute - funded the Center for Health Market Innovations

The Green Revolution

Agriculture was introduced to the Natural Sciences division of the foundation in the major reorganization of 1928. In 1941, the foundation gave a small grant to Mexico for maize research, in collaboration with the then new president, Manuel Ávila Camacho. This was done after the intervention of vice-president Henry Wallace and the involvement of Nelson Rockefeller; the primary intention being to stabilise the Mexican Government and derail any possible communist infiltration, in order to protect the Rockefeller family's investments.[35]

By 1943 this program, under the foundation's Mexican Agriculture Project, had proved such a success with the science of corn propagation and general principles of agronomy that it was exported to other Latin American countries; in 1956 the program was then taken to India; again with the geopolitical imperative of providing an antidote to communism.[35] It wasn't until 1959 that senior foundation officials succeeded in getting the Ford Foundation (and later USAID, and later still, the World Bank) to sign on to the major philanthropic project, known now to the world as the Green Revolution. It was originally conceived in 1943 as CIMMYT, the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center in Mexico. It also provided significant funding for the International Rice Research Institute in the Philippines. Part of the original program, the funding of the IRRI was later taken over by the Ford Foundation.[35]

Costing around $600 million, over 50 years, the revolution brought new farming technology, increased productivity, expanded crop yields and mass fertilization to many countries throughout the world. Later it funded over $100 million of plant biotechnology research and trained over four hundred scientists from Asia, Africa and Latin America. It also invested in the production of transgenic crops, including rice and maize. In 1999, the then president Gordon Conway addressed the Monsanto Company board of directors, warning of the possible social and environmental dangers of this biotechnology, and requesting them to disavow the use of so-called terminator genes;[36] the company later complied.

In the 1990s, the foundation shifted its agriculture work and emphasis to Africa; in 2006 it joined with the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation in a $150 million effort to fight hunger in the continent through improved agricultural productivity. In an interview marking the 100 year anniversary of the Rockefeller Foundation, Judith Rodin explained to This Is Africa that Rockefeller has been involved in Africa since their beginning in three main areas - health, agriculture and education, though agriculture has been and continues to be their largest investment in Africa.[37]

Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center

The foundation also owns and operates the Rockefeller Foundation Bellagio Center in Bellagio, Italy. The Center comprises several buildings, spread across a 50-acre (200,000 m2) property, on the peninsula between lakes Como and Lecco in Northern Italy. The Center is sometimes colloquially referred to as the Villa Serbelloni. The Villa is only one of the many buildings in which residents and conference participants are housed. The property was bequeathed to the Foundation in 1959 under the presidency of Dean Rusk (who was later to become U.S. President Kennedy's secretary of state). The Bellagio Center operates both a conference center and a residency program.[38] The residency program is a highly competitive program to which scholars, artists, writers, musicians, scientists, policymakers and development professionals from around the world can apply to work on a project of their own choosing for a period of four weeks. The essence of the program is the synergy obtained by the interaction between people coming from the most diverse backgrounds. Numerous Nobel laureates, Pulitzer winners, National Book Award recipients, Prince Mahidol Award winners and MacArthur fellows, as well as several acting and former heads of State and Government, have been in residence at Bellagio.

Family involvement

The Rockefeller family helped lead the foundation in its early years, but later limited itself to one or two representatives, to maintain the foundation's independence and avoid charges of undue family influence. These representatives have included the former president John D. Rockefeller 3rd, and then his son John D. Rockefeller, IV, who gave up the trusteeship in 1981. In 1989, David Rockefeller's daughter, Peggy Dulany, was appointed to the board for a five-year term.

In October 2006, David Rockefeller, Jr. joined the board of trustees, re-establishing the direct family link and becoming the sixth family member to serve on the board. By contrast, the Ford Foundation has severed all direct links with the Ford family.

Stock in the family's oil companies is a major part of the foundation's assets, beginning with Standard Oil and now with its corporate descendants, including Exxon Mobil.[39]

Historical legacy

The second-oldest major philanthropic institution in America, after the Carnegie Corporation, the foundation's impact on philanthropy in general has been profound. It has supported United Nations programs throughout its history, such as the recent First Global Forum On Human Development, organized by the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) in 1999.[40]

The early institutions it set up have served as models for current organizations: the UN's World Health Organization, set up in 1948, is modeled on the International Health Division; the U.S. Government's National Science Foundation (1950) on its approach in support of research, scholarships and institutional development; and the National Institute of Health (1950) imitated its longstanding medical programs.[41]

Current trustees

- As of December 27, 2012[42]

- Ann M. Fudge, 2006-, former chairman and CEO, Young & Rubicam Brands, New York.

- Helene D. Gayle, 2009-, president and CEO of CARE.

- Alice S. Huang, Senior Faculty Associate, California Institute of Technology.

- Martin L. Leibowitz, 2012-, Managing Director, Morgan Stanley; formerly TIAA-CREF (1995 to 2004) and 26 years with Salomon Brothers

- Monica Lozano, 2012-, CEO, ImpreMedia, LLC

- Strive Masiyiwa, 2003-, Zimbabwean businessman and cellphone pioneer, founding Econet Wireless.

- Diana Natalicio, 2004-, President, The University of Texas at El Paso

- Sandra Day O'Connor, 2006-, Associate Justice, Retired, Supreme Court of the United States, Washington, D.C. (First woman appointed to the Supreme Court.)

- Ngozi Okonjo-Iweala, 2009-, Finance Minister of Nigeria; former Managing Director of the World Bank; former Foreign Minister of Nigeria.

- Richard Parsons, 2007-, Chairman of the Board, Citigroup Inc.

- David Rockefeller, Jr., 2006-, Chair of foundation board Dec. 2010- ; Vice Chairman of Rockefeller Family & Associates; Director and former Chair, Rockefeller & Co., Inc.; current Trustee of the Museum of Modern Art.

- Judith Rodin, President of the Foundation; ex-officio member of Board

- John Rowe, 2007-, professor at the Columbia University Mailman School of Public Health; former Chairman and CEO of Aetna Inc.

Notable past trustees

- Alan Alda, 1989–1994 - Actor and film director.

- Winthrop W. Aldrich 1935–1951 - Chairman of the Chase National Bank, 1934–1953; Ambassador to the Court of St. James, 1953-1957.

- John W. Davis 1922–1939 - J. P. Morgan's private attorney; founding president of the Council on Foreign Relations.

- C. Douglas Dillon 1960–1961 - US Treasury Secretary, 1961–1965; Member of the Council on Foreign Relations.

- Orvil E. Dryfoos 1960–1963 - Publisher of the New York Times, 1961-1963.

- Peggy Dulany, 1989–1994 - Fourth child of David Rockefeller; Founder and president of Synergos.

- John Foster Dulles 1935–1952 {Chairman} - US Secretary of State, 1953–1959; Senior partner, Sullivan & Cromwell law firm.

- Charles William Eliot 1914–1917 - President of Harvard, 1869-1909.

- John Robert Evans 1982 -1996 {Chairman} - President of the University of Toronto 1972-1978; founding Director of the Population, Health and Nutrition Department of the World Bank

- Frederick Taylor Gates 1913–1923 - John D. Rockefeller Sr.'s principal advisor.

- Stephen Jay Gould 1993–2002 - Author; Professor and Curator, Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University.

- Rajat Gupta, 2006–11, former director, Goldman Sachs, Procter & Gamble, AMR Corporation; Special Advisor to the UN Secretary-General; former Managing Director, McKinsey & Company.

- Wallace Harrison 1951–1961 - Rockefeller family architect; lead architect for the UN Headquarters complex.

- Thomas J. Healey, 2003–2012, Partner, Healey Development LLC; teaching course at Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government; formerly with Goldman, Sachs and an Assistant Secretary of the U.S. Treasury.

- Charles Evans Hughes 1917-1921;1925–1928 - Chief Justice of the United States, 1930-1941.

- Robert A. Lovett 1949–1961 - US Secretary of Defense, 1951-1953.

- Yo-Yo Ma 1999–2002 - Cellist.

- Jessica T. Mathews, President, Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Washington, D.C.

- John J. McCloy Chairman: 1946-1949; 1953–1958 - Prominent US Presidential Advisor; Chairman of the Ford Foundation, 1958–1965; Chairman of the Council on Foreign Relations.

- Bill Moyers 1969–1981 - Journalist.

- James F. Orr, III, (Board Chair), President and Chief Executive Officer, LandingPoint Capital, Boston, Massachusetts.

- Surin Pitsuwan, 2010–2012, Secretary general of ASEAN (2007-2012)[43] and Thai politician.

- Mamphela Ramphele, Chairperson, Circle Capital Ventures, Cape Town, South Africa.

- John D. Rockefeller 1913-1923.

- John D. Rockefeller, Jr. Chairman: 1917-1939.

- John D. Rockefeller 3rd Chairman: 1952-1972.

- John D. Rockefeller, IV 1976-81.

- Julius Rosenwald 1917–1931 - Chairman of Sears Roebuck, 1932-1939.

- Dean Rusk 1950–1961 - US Secretary of State, 1961-1969.

- Raymond W. Smith, Chairman, Rothschild, Inc., New York; Chairman of Arlington Capital Partners; Chairman of Verizon Ventures; and a Trustee of the Carnegie Corporation of New York.

- Frank Stanton 1961-1966? - President of CBS, 1946-1971.

- Arthur Hays Sulzberger 1939–1957 - Publisher of the New York Times, 1935-1961.

- Paul Volcker 1975–1979 - Chairman, Board of Governors, Federal Reserve Board; President, New York Federal Reserve Bank.

- Thomas J. Watson, Jr 1963-1970?[44] - President of IBM, 1952-1971.

- James Wolfensohn - former President of the World Bank.

- George D. Woods 1961-1967? - President of the World Bank, 1963-1968.

- Vo-Tong Xuan, 2002–2010, Vice President for Academic Affairs, Tan Tao University, Ho Chi Minh City; former rector of An Giang University, the second university in Vietnam's Mekong Delta.

- Owen D. Young 1928–1939 - Chairman of GE, 1922–1939, 1942-1945.

Presidents

- Judith Rodin - 2005- ; former president of the University of Pennsylvania, and provost, chair of the Department of Psychology, Yale University.

- Gordon Conway - 1998-2004; an agricultural ecologist and former President of the Royal Geographical Society.

- Peter Goldmark, Jr. - 1988-1997; former executive director of the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey.[45]

- Richard Lyman - 1980-1988; president of Stanford University (1970–1980).

- John Knowles - 1972-1979; physician, general director of the Massachusetts General Hospital (1962–1971).[46]

- J. George Harrar - 1961-1972; plant pathologist, "generally regarded as the father of 'the Green Revolution.'"[47]

- Dean Rusk - 1952-1961; United States Secretary of State from 1961 to 1969

- Chester Barnard - 1948-1952; Bell System executive and author of landmark 1938 book, The Functions of the Executive

- Raymond Fosdick - 1936-1948; brother of American clergyman Harry Emerson Fosdick

- Max Mason - 1929-1936

- George E. Vincent - 1917-1929; member of the John D. Rockefeller/Frederick T. Gates General Education Board (1914–1929)[48]

- John D. Rockefeller, Jr. - 1913-1917.

Bibliography

- Berman, Edward H. The Ideology of Philanthropy: The influence of the Carnegie, Ford, and Rockefeller foundations on American foreign policy, New York: State University of New York Press, 1983.

- Brown, E. Richard, Rockefeller Medicine Men: Medicine and Capitalism in America, Berkeley: University of California Press, 1979.

- Chernow, Ron, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., London: Warner Books, 1998.

- Dowie, Mark, American Foundations: An Investigative History, Boston: The MIT Press, 2001.

- Fisher, Donald, Fundamental Development of the Social Sciences: Rockefeller Philanthropy and the United States Social Science Research Council, Michigan: University of Michigan Press, 1993.

- Fosdick, Raymond B., John D. Rockefeller, Jr., A Portrait, New York: Harper & Brothers, 1956.

- Fosdick, Raymond B., The Story of the Rockefeller Foundation, New York: Transaction Publishers, Reprint, 1989.

- Harr, John Ensor, and Peter J. Johnson. The Rockefeller Century: Three Generations of America's Greatest Family. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1988.

- Harr, John Ensor, and Peter J. Johnson. The Rockefeller Conscience: An American Family in Public and in Private, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1991.

- Jonas, Gerald. The Circuit Riders: Rockefeller Money and the Rise of Modern Science. New York: W.W. Norton and Co., 1989.

- Kay, Lily, The Molecular Vision of Life: Caltech, the Rockefeller Foundation, and the Rise of the New Biology, New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.

- Lawrence, Christopher. Rockefeller Money, the Laboratory and Medicine in Edinburgh 1919-1930: New Science in an Old Country, Rochester Studies in Medical History, University of Rochester Press, 2005.

- Nielsen, Waldemar, The Big Foundations, New York: Cambridge University Press, 1973.

- Nielsen, Waldemar A., The Golden Donors, E. P. Dutton, 1985. Called Foundation "unimaginative ... lacking leadership and 'slouching toward senility.'"[45]

- Palmer, Steven, Launching Global Health: The Caribbean Odyssey of the Rockefeller Foundation, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2010.

- Rockefeller, David, Memoirs, New York: Random House, 2002.

- Shaplen, Robert, Toward the Well-Being of Mankind: Fifty Years of the Rockefeller Foundation, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964.

- Theiler, Max and Downs, W. G., The Arthropod-Borne Viruses of Vertebrates: An Account of The Rockefeller Foundation Virus Program, 1951-1970. (1973) Yale University Press. New Haven and London. ISBN 0-300-01508-9.

See also

References

- 1 2 FoundationCenter.org, The Rockefeller Foundation, accessed 2010-12-23

- 1 2 Rockefeller Foundation. Our Work. Retrieved 2015-08-30.

- ↑ "Company Overview of The Rockefeller Foundation". Businessweek. Retrieved 17 April 2013.

- ↑ The Rockefeller Foundation Annual Report 1913-14

- ↑ "Our History - A Powerful Legacy". The Rockefeller Foundation.

- ↑ Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, History

- ↑ Harvard School of Public Health, History

- ↑ Friedland, Martin L. (2002). The University of Toronto : a history. Toronto [u.a.]: Univ. of Toronto Press. ISBN 0-8020-4429-8.

- ↑ National Library of Medicine

- ↑ Wilbur A Sawyers Papers

- ↑ "History", The New School for Social Research webpage. Retrieved 2013-02-17.

- ↑ Edwin Black (September 2003). "The Horrifying American Roots of Nazi Eugenics". History News Network. (Also published at San Francisco Chronicle). According to HNN, this material was drawn from Black's books "IBM and the Holocaust" and "War Against the Weak: Eugenics and America's Campaign to Create a Master Race".

- ↑ The Foundation Center

- ↑ "Judith Rodin, Rockefeller Foundation CEO: 'Culture Eats Strategy for Lunch'". Forbes. Retrieved 11 March 2013.

- 1 2 The Rockefeller Foundation Timeline

- 1 2 3 4 Details of the establishment and future legacy of the Rockefeller Foundation - see Ron Chernow, Titan: The Life of John D. Rockefeller, Sr., New York: Warner Books, 1998, (pp. 563-566)

- ↑ Rockfound.org, history, 1913-1919

- ↑ Seim, David L. (2013) Rockefeller Philanthropy and Modern Social Science London: Pickering & Chatto, pp. 81-89.

- ↑ Foundation withdrew from direct involvement in Industrial Relations - see Robert Shaplen, Toward the Well-Being of Mankind: Fifty Years of the Rockefeller Foundation, New York: Doubleday & Company, Inc., 1964, (p.128)

- ↑ Seim, David L. (2013), pp. 103-12

- ↑ Schmuhl, Hans Walter (2008). Kaiser Wilhelm Institute for Anthropology, Human Heredity and Eugenics, 1927-1945. [Dordrecht, Netherlands]: Springer. p. 87.

- ↑ (Gretchen Schafft, From Racism to Genocide: Anthropology in the Third Reich. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2004)

- ↑ Jan A. Witkowski, "Charles Benedict Davenport, 1866-1944," in Jan A. Witkowski and John R. Inglis, eds., Davenport’s Dream: 21st Century Reflections on Heredity and Eugenics (Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press, 2008), p. 52.

- ↑ Early backing of Henry Kissinger - see Walter Isaacson, Kissinger: A Biography, New York: Simon & Schuster, (updated) 2005, (p.72)

- ↑ Rockefeller Archive Center: Main subject areas.

- ↑ Birn, Anne-Emanuelle; Armando Solórzano (1999). "Public health policy paradoxes: science and politics in the Rockefeller Foundation's hookworm campaign in Mexico in the 1920s". Social Science & Medicine. 49 (9): 1197. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00160-4.

- ↑ Birn, Anne-Emanuelle; Armando Solórzano (1999). "Public health policy paradoxes: science and politics in the Rockefeller Foundation's hookworm campaign in Mexico in the 1920s". Social Science & Medicine. 49 (9): 1197–1210. doi:10.1016/S0277-9536(99)00160-4.

- ↑ Birn, Anne-Emanuelle; Armando Solórzano (1999). "Public health policy paradoxes: science and politics in the Rockefeller Foundation's hookworm campaign in Mexico in the 1920s". Social Science & Medicine. 49 (9): 1209–1210. doi:10.1016/s0277-9536(99)00160-4. PMID 10501641.

- ↑ Major rescue program of European scholars - see John Ensor Harr and Peter J. Johnson, The Rockefeller Century: Three Generations of America's Greatest Family, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1988. (pp.401-03)

- ↑ Medical Sciences Division and Alfred Kinsey funding - Ibid., (p.456)

- ↑ Theiler, Max; Downs, W. G. (1973). The Arthropod-Borne Viruses of Vertebrates: An Account of The Rockefeller Foundation Virus Program, 1951-1970. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. pp. xvii, xx. ISBN 0-300-01508-9.

- ↑ "Charities Try to Keep Up With the Gateses" New York Times, 2007

- ↑ Funding of programs and fellowships at major universities, foreign policy think tanks and research councils - see Robert Shaplen, op, cit., (passim)

- ↑ AFP Online

- 1 2 3 The story of the Foundation and the Green Revolution - see Mark Dowie, American Foundations: An Investigative History, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, 2001, (pp.105-140)

- ↑ Biotech-info.net: "The Rockefeller Foundation and Plant Biotechnology"

- ↑ "A century of innovation? Philanthropy and the African growth story". Retrieved 5 August 2013.

- ↑ The Bellagio Center. The Rockefeller Foundation. Retrieved on 2013-08-24.

- ↑ Share portfolio - see Waldemar Nielsen The Big Foundations, New York: Columbia University Press, 1972. (p.72)

- ↑ Global Forum on Human Development. Hdr.undp.org. Retrieved on 2013-08-24.

- ↑ As model for UN organizations - Ibid., (pp.64-5)

- ↑ Board of Trustees, foundation webpage plus associated bio pages on members. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ Parameswaran, Prashanth, "Outgoing ASEAN Chief’s Farewell Tour", The Diplomat, December 19, 2012. Retrieved 2012-12-27.

- ↑ RF Annual Report 1969, p. VI. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- 1 2 Teltsch, Kathleen, "Rockefeller Foundation Selects a New President", The New York Times, May 8, 1988. Goldmark was son of Peter Carl Goldmark. See Blumenthal, Ralph, "Remembering the Travel Scandal at the Port Authority", The New York Times City Room blog, June 24, 2008 4:41 pm ET. Both retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ↑ John Hilton Knowles Papers, The Rockefeller Archive Center. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ↑ J. George Harrar Papers, The Rockefeller Archive Center. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

- ↑ George E. Vincent Papers, The Rockefeller Archive Center. Retrieved 2011-01-09.

Further reading

- CFR Website - Continuing the Inquiry: The Council on Foreign Relations from 1921 to 1996 The history of the Council by Peter Grose, a Council member - mentions financial support from the Rockefeller foundation.

- Interview with Norman Dodd An investigation of a hidden agenda within tax-free foundations, including the Rockefeller Foundation (Video).

- Foundation Center: Top 100 US Foundations by total giving

- New York Times: Rockefeller Foundation Elects 5 - Including Alan Alda and Peggy Dulany

- SFGate.com: "Eugenics and the Nazis: the California Connection"

- Press for Conversion! magazine, Issue # 53: "Facing the Corporate Roots of American Fascism," Bryan Sanders, Coalition to Oppose the Arms Trade, March 2004

External links

- Rockefeller Foundation website, including a timeline

- Hookworm and malaria research in Malaya, Java, and the Fiji Islands; report of Uncinariasis commission to the Orient, 1915-1917 The Rockefeller foundation, International health board. New York 1920