Robert Campbell (frontiersman)

| Robert Campbell | |

|---|---|

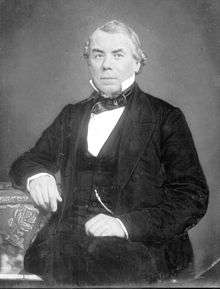

Photograph of Robert Campbell circa 1860 | |

| Born |

February 12, 1804 County Tyrone, Ireland |

| Died |

October 16, 1879 (aged 75) St. Louis, Missouri, US |

| Known for | Exploration of Rocky Mountains, Head of two Missouri Banks, Owner of Steamboats, Real Estate Mogul in St. Louis, Missouri and Kansas City, Missouri |

| Website | Campbell House Museum Website |

For a list of other individuals by the same name, see Robert Campbell.

Robert Campbell (February 12, 1804 – October 16, 1879) was an Irish immigrant who became an American frontiersman, fur trader and businessman. His St. Louis home is now preserved as a museum; the Campbell House Museum.

Early life

Robert Campbell was born on February 12, 1804, in his family’s home, Aughalane (pronounced “Ochalane”). The house was built by Hugh Campbell in 1786 near Plumbridge, County Tyrone, Ireland. Hugh placed a pair of stone plaques above the door, inscribing one with his name and the other with the coat of arms of the Duke of Argyll, indicating kinship with the Campbells in Scotland. Aughalane is today preserved by the Ulster American Folk Park in Castletown, County Tyrone.[1]

Campbell was the youngest child of his father's second wife, and therefore was due to inherit next to nothing. This prompted him to follow his older brother Hugh to America, arriving in Philadelphia on June 27, 1822. How he spent his first year is largely unknown, but a meeting with John O’Fallon in 1823 offered potential. Like Robert, O’Fallon was an immigrant from County Tyrone who now lived in St. Louis, and was employed as a sutler at Council Bluffs. Robert was offered the position of assistant clerk, working the winter at Bellevue on the Missouri River (near present-day Omaha, Nebraska). Robert, who had lung issues as a child, suffered greatly through the winter, and he moved to O’Fallon’s St. Louis store. O’Fallon introduced him to Doctor Bernard Farrar, who advised Robert, “your symptoms are consumptive and I advise you to go to the Rocky Mountains. I have before sent two or three young men there in your condition, and they came back restored to health and healthy as bucks.”[2]

Initial Western Expedition (1825 - 1829)

Campbell joined fur trader Jedediah S. Smith in an expedition leaving St. Louis for the Rocky Mountains on November 1, 1825. With the financial backing of William H. Ashley and his Rocky Mountain Fur Company, Smith assembled a group of sixty men, including experienced explorers and traders Hiram Scott, Jim Beckwourth, Moses Harris, and Louis Vasquez. After becoming aware of Campbell's skills and education, Smith asked him to act as clerk for the expedition.

Campbell's initial journey into the American west included a harsh winter spent with Pawnee tribesmen south of the Platte River. After the spring thaw, the group traveled north of the Platte River to the traders' Rendezvous in Cache Valley, in modern Utah and southern Idaho. There Ashley sold his percentage of the expedition to Smith, David Edward Jackson, and William Sublette. The expedition then split into two branches. Smith struck off to the southwest while Jackson and Sublette moved northwest to the Teton range and the Snake River. Campbell traveled with the Jackson/Sublette party, and later wrote that the group ...hunted along the forks of the Missouri, following the Gallatin, and trapped along across the headwaters of the Columbia.[3] The group wintered, once again together, in Cache Valley during the winter of 1826-27.

In late 1827, Campbell led a party into Flathead territory and suffered losses to Indian attack. Many survivors of his small group decided to winter in Flathead territory, but Campbell and two other left to contact the larger party wintering in Cache Valley. Traveling slowly due to harsh weather, they arrived at the Hudson's Bay Company camp of Peter Skene Ogden on the Snake River in February 1828. After leaving word of their whereabouts, Campbell returned and finished the winter with his men in Flathead territory.

In the spring of 1828 the group trapped along Clark's Fork and Bear Lake. They were attacked by Blackfeet on their way to the summer rendezvous, but suffered light losses and brought in their beaver pelts. After the summer trading, Campbell joined Jim Bridger in a trapping expedition to Crow country in northeastern Wyoming, wintering in the Wind River area. In the spring of 1829, Campbell decided to return briefly to Ireland to see to family affairs. Entrusted with forty-five packs of beaver skins by the larger group, he arrived in St. Louis in late August. He sold the furs for ...$22,476 dollars and received payment for his services amounting to $3,016.[4]

Pierre's Hole and Fort William (1832-1835)

When Campbell returned to the west, he was asked by William Sublette to form a partnership. Sublette would even agree to an odd relationship for the first year, making Robert a lieutenant but having him purchase his own goods for rendezvous, using the sale of this merchandise as the stake he needed to officially join the business.[5] William Clark granted Robert and William Sublette’s new company a nominally-legal liquor license, enabling them to carry 450 gallons of extremely valuable whiskey to the next rendezvous.

The successful trapping season in 1832 concluded with the famous Battle of Pierre's Hole. As the rendezvous at Pierre’s Hole was breaking up, a group of Gros Ventres (sometimes mistaken as Blackfeet), who had been dogging the trappers as they arrived, bumped into a trapping brigade as it left the valley, sparking a full-fledged battle. The Gros Ventres built quick fortifications out of downed logs as trapper reinforcements arrived, commencing a day-long siege. Between three and twelve trappers were killed, and nine to fifty Gros Ventres. The Natives were able to retreat during the night. Robert, who was interrupted in the middle of writing a letter to his brother, joined the fighting. Sublette and Robert agreed to dispose of each other’s property, in the event of one’s death. Both men led a charge on the Indian defenses, with Robert at one point believing he had been wounded, and Sublette taking a bullet in the arm. Robert helped Sublette from the field. The Battle of Pierre’s Hole would later be dramatized in Washington Irving’s The Adventures of Captain Bonneville (1837).[6]

Sublette and Robert shifted their focus from the rendezvous to challenging John Jacob Astor’s American Fur Company by building forts adjacent to Astor’s. Robert built Fort William in 1833 near the mouth of the Yellowstone River. The fort dealt primarily in buffalo robes from local Native American tribes, primarily the Assiniboine, Cree, and Gros Ventres. Fort William and its nearby rival, Fort Union, competed for loyalty from the Chiefs through gifts, generous deals, and alcohol. Robert proved an able diplomat, notably securing the loyalty of a Cree chief named Sonnant, but he was otherwise frustrated and depressed during his time at Fort William. Their company was successful, however, and Astor’s company paid them to leave the area.

The fur trade was quickly dying, and Sublette and Campbell opted to close down their last outpost and concentrate on the buffalo robe trade and dry goods. They left at just the right time: in 1835, their robes sold for more than beaver pelts for the first time. Robes had risen to $6 each by the end of the decade, while beaver had fallen to $2.50 as the beaver population plummeted and the market turned increasingly to silk.[7]

Sublette and Campbell (1836-1845)

St. Louis, as the base of operations for the fur trade, was a natural place for Sublette and Campbell to open their business. In September 1836 the partners purchased a brick building at 7 Main Street for $12,823. From here, they engaged in the dry goods business, frequently selling on credit. Robert demonstrated a keen knowledge of affairs of money. In the age of unbridled capitalism, Robert proved to be firm yet just, pursuing payments of debts owed, but always paying his own debts. He never really pursued the robber baron practices of later in the century.[8]

Campbell and Sublette amassed large amounts of real estate in the upper Mississippi valley, severed as loan agents for several banks, and invested in the St. Louis Insurance Company, the St. Louis Hotel Company, and the Marine Insurance Company. All of this investment, however, threatened to overextend the partners. They frequently teetered on the edge of bankruptcy because of difficulty in collecting from their debtors. Despite these issues, Campbell continued to rise through the ranks of society. He was elected by the state legislature to the Missouri State Bank’s board of directors in December 1839. Although he rarely had much cash on hand, he was financially sound enough to purchase a large tract of land in what is today Kansas City’s downtown.[9]

1842 saw the end of "Sublette and Campbell," as the partners decided not to renew their partnership. Both remained good friends, however, and the store was simply divided down the center by a wall. An economic crisis in the 1840s threatened to ruin Campbell, but the timely influx of cash from Scottish Laird (Lord) Sir William Drummond Stewart, a good friend, prevented much worse. Sublette would become seriously ill and die in 1845, depriving Robert of a close friend and ally.[10]

Expansion (1845-1860)

Campbell was highly successful in the remainder of the 1840s. He was elected as the President of the State Bank of Missouri in 1846, increasing its deposits and value of its notes. Robert’s stewardship of the bank was highly successful, and bank notes signed by him were accepted across the nation. The position also came with a $3,000 annual salary. Robert succeeded in finding a new partner as well, William Campbell (no relation), forming the firm “R. and W. Campbell” in 1848. The new firm invested in railroads and steamboats, and was also successful at placing allies as sutlers in several western forts.[11]

Campbell was long recognized as a man capable of understanding the West. Thus, when the Mexican-American War broke out in 1846, Robert was appointed a state militia colonel charged with raising and outfitting 400 cavalry volunteers. Victory for the United States enabled Campbell to begin expanding his business into the American Southwest along the El Paso Trail. Campbell also outfitted John C. Fremont’s 1843 Expedition of exploration in the region. His involvement with famous figures of the west extended beyond military matters as well. Father Pierre-Jean De Smet, the famous Jesuit missionary, had several interactions with Campbell throughout the years. Because of his experiences in the west, the United States government called upon Campbell to participate in the negotiations for the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. The fort had in fact once been owned by Campbell and Sublette, under the name Fort William (this is not to be confused with the 1833 Fort William, on the Yellowstone River).[12][13]

Twin disasters in 1849 threatened the prosperity of St. Louis. First, a cholera epidemic hit the city. In July, a fire broke out along the waterfront and quickly spread. The fire destroyed $6.1 million in property, including Campbell's store. Robert Campbell would rebound his business quite well, using the insurance money to pay off the lingering debts of “Sublette and Campbell,” as well as purchase a new site for R. & W. Campbell.[14] St. Louis continued to prosper as well. The boom brought Robert to new fields of exploitation. The robe trade on the upper Missouri continued to reap profits, and Campbell’s credit was accepted more regularly by western traders than that of the United States government, largely because Campbell was deemed more trustworthy. Steamboats continued to rise in importance. Campbell purchased the “A. B. Chambers” in 1858 for $833.32, paid in three installments. This boat would be the first piloting job of Samuel Clemens. The Mississippi and Missouri Rivers were risky to invest heavily in, and the “A. B. Chambers” had snagged and sunk by 1860. Even then, Robert was able to turn a profit, benefitting from the $9,480 insurance claim.[15]

The Civil War

Living in Missouri in the American Civil War required a delicate balancing act between pro-Southern and Unionist forces and interests. As the pivotal election of 1860 approached, Robert dismissed the fire-eating southerners as noisy and full of empty bombast. When the Secession Crisis began, Campbell declared early on as a Conditional Unionist, supporting Union with slavery. He was thus a backer of the Crittenden Compromise of 1861, intended to avoid the full outbreak of war. Campbell was influential enough that he was elected as President of the Conditional Unionists at a city convention on January 12, 1861. The convention voted to support slavery as a constitutional right, and urging the Federal government to restrain from using force during the crisis.[16]

While Robert supported the right of men to own slaves, he himself had emancipated his final slave several years before. In 1857, Robert freed his slave Eliza and her two sons, apparently because his wife Virginia had grown distasteful of the institution. Robert therefore occupied a complicated point of view common to many at the time, viewing slavery as necessary and the law, but not morally pure.[17] After the initial crisis in 1861, Campbell undertook few overt political roles for most of the war, instead focusing on business. He supplied troops for most of the war, including a large contract dispensing payroll to troops in New Mexico. The disruption of Mississippi River traffic slowed business, and even when it had reopened, the government would sometimes requisition Robert’s ships. On one such trip, the “Robert Campbell” was apparently sabotaged and destroyed by a Confederate partisan.[18]

When Robert did involve himself in politics, it was generally in opposition to radical Republican policy. Robert supported his neighbor and commander of Union forces in Missouri, General William Harney, and also his successor and friend, General John Frémont. Robert also attempted to secure freedom for friends arrested under the strict martial law. Such activities were not without their dangers. Several St. Louis citizens expressed doubts over the loyalty of Robert and his brother Hugh. Adding to the doubts was the fact both Campbells had married Southern women. Despite the political strength of the Republicans, both Campbells were able to emerge from the war with their reputations intact. Although Robert probably disliked the loyalty oaths required by Special Order No. 80, he signed his in September 1862, ensuring he remained in the upper echelons of society.[19]

Later career

Robert’s businesses continued to expand to ever further extents in the later years of his life. In 1871, the Campbell business empire extended all the way to El Paso, Texas, where Robert purchased land at a bankruptcy auction. Unfortunately for him, the land would become entangled in courts, bedeviling Robert’s efforts to do something with it for the remainder of his life. More successful business ventures included a foray into gold mining. Miners would send Robert gold dust, which he would then ship east to Stuart & Brothers of Philadelphia to be converted into coinage. Robert shipped about 497 ¼ pounds of gold dust between 1867–70, worth $102,915.02.[20]

In 1866, Robert also purchased the Southern Hotel, making it the flagship of his real estate empire. The hotel had taken 15 years to develop, and had generally underperformed for years. After purchasing it, the hotel underwent a major renovation costing $60,000. Robert improved nearly every room, and the St. Louis Republican declared that it was the finest hotel in the city. Unfortunately for Robert, he also installed a steam heating system in the hotel. Just after midnight on April 11, 1877, the system started a fire that soon engulfed the entire six-story structure. Every fire engine in the city was involved in the effort to save the 150 staff and guests. 14 guests were killed, and property damage was estimated at $1.5 million. One fireman, Phelim O’Toole, was signaled out for his bravery. Robert was left to lament the destruction of the hotel. He remarked shortly after that the $492,000 insurance check was at least $100,000 shy of the building’s value. While he planned to redevelop the site, he was unable to formalize plans before his death.[21]

The late 1860s and 1870s saw the Campbell family at the height of their political and social influence. General Ulysses Grant was elected President in 1868, and the Campbell family enjoyed close relationships with the Grant family. The Campbells hosted Grant and other guests on at least three occasions (although Robert was absent for one), and Robert also visited the White House. Robert’s connections to Grant, coupled with his extensive experience with the Native American tribes of the West, led to his appointment in 1869 to the Board of Indian Commissioners. Men on the board were supposed to be honest and wealthy enough to not be tempted to abuse their position, so as to help root out corruption. Campbell travelled through the west, meeting various tribes including the Ute, Cherokee, and the Oglala chief Red Cloud. The Commissioners ultimately recommended that the Native Americans be assimilated into white society, encouraging the abolition of tribal sovereignty and more extensive cultural retraining. They also charged the high level of corruption of the Indian Bureau as problematic. With the Commission unable to make any headway against that corruption, every member, including Robert, resigned in protest in May 1874.[22]

Robert’s health declined considerably throughout the 1870s. His lung problems, which had never fully been resolved, continued to plague him. A particularly bad attack afflicted him during a dinner party for General William Sherman, forcing Robert to be confined to his bed for a month. In an effort to recover his strength, the Campbells travelled to Saratoga Springs. Despite these efforts, his health continued to deteriorate. On October 16, 1879, Robert had difficulty breathing and was suffering from severe pains. He died that evening, and was buried in Bellefontaine Cemetery on October 19. The funeral crowd was so large that it could not fit in the parlor, and so spilled into the hallway and the morning room.[23]

Personal life

Campbell met his future wife Virginia Campbell in Philadelphia in 1835. Virginia Kyle's cousin, Mary Kyle, was married to Hugh Campbell, Robert's older brother. At the time they met, Robert was in poor health and Virginia helped to nurse him. He soon became smitten, and they exchanged letters in a lengthy courtship strained by the age difference (Campbell was 31, Virginia 13) and distance. They also fought the disapproval of family and friends. Neither Hugh Campbell nor William Sublette believed that anything good would come of this relationship. In 1838, Robert asked Virginia for her hand in marriage, and she accepted. Robert joyfully asked permission from her mother, Lucy Ann Winston Kyle, who refused, declaring that Virginia was too young at the age of 16 to be married. She did allow Virginia and Robert to continue corresponding.[24]

In the summer of 1839, Virginia abruptly asked to be released from the engagement. In what was undoubtedly a heartfelt letter for Robert (but horribly sappy by modern standards), he consented even as he wrote, “You have blighted the happiness through life of a heart that loved only you.” Robert’s feelings never wavered, and Mrs. Kyle grew increasingly wary of Virginia’s new suitors. Mrs. Kyle signaled her preference of Robert in December 1840, mere days before Robert penned a letter to Virginia that indicated his still-flaming love for her. The pair of letters evidently did the trick, as Virginia accepted his renewed proposal for marriage. Robert and Virginia were married in North Carolina on February 25, 1841.[25]

Robert and Virginia first lived at the Planter’s House on 4th Street, in a suite that cost $13.75 per week. The Planter’s House Hotel was the first-class hotel of St. Louis, unrivaled for a dozen years. The Campbell household would begin expanding as well. The first son, named James Alexander, was born on May 14, 1842. James was followed by Hugh in 1843; however, Hugh would not even see his first birthday, as he died of pneumonia. Several more children followed, and as typical of the time, the family reused names, resulting in a second Hugh. With the family expanding, the Campbells began renting a house on 5th Street in 1843. The owners of the property took a number of loans that they were unable to pay back, resulting in the land being seized in 1847 and put up for sale. Robert was concerned enough about the fate of his house that he purchased the property directly. Despite the larger house, the Campbells continued to suffer loss. Two years later, the Campbell life—and the rest of the city of St. Louis—were challenged, for in 1849 a cholera epidemic swept through the city.The disease peaked in July, killing 145 people in one day, 722 in one week, and, from January to the end of July, 4,547. Among those who fell was the Campbell’s first born, James, who died on June 18. The disease also nearly took the second Hugh, but he managed to survive.[26]

Many residents of the city now desired to leave the unhealthy conditions downtown, paving the way for the rise of Lucas Place in the 1850s. Robert purchased 20 Lucas Place on November 8, 1854, paying $13,677 to live in the exclusive, elite neighborhood. Despite the move, the Campbell’s health woes would not abate. All told, the Campbells would have 13 children, of whom only three would survive until adulthood. Together, Hugh, Hazlett, and James would own and live in their father’s house for the remainder of their lives. The Campbells were also joined by several family members. Lucy Kyle accepted their invitation to move in and joined the family in 1856. Robert’s brother Hugh joined the family in St. Louis in 1859, when he and his wife moved into a house on Washington Avenue. Other family members, including Eleanor Otey (Virginia's sister) and several of Robert’s Irish relations, also resided at the house for various periods. Hugh would then become Robert’s unofficial business partner.[27]

Robert died on October 16, 1879, followed by Virginia in 1882. They are buried with their children in Bellefontaine Cemetery.[28] The three surviving children never married and remained at the Campbell House at 20 Lucas Place (now 1508 Locust St) until the death of the final son in 1938. The home is now preserved as the Campbell House Museum, complete with the original furnishings and decorations.

References

- ↑ National Museums Northern Ireland, “Campbell House,” nmni.com, http://www.nmni.com/uafp/Collections/Buildings/Ulster-Buildings/Campbell-House (Accessed 09/11/2014)

- ↑ Nester, William R. (2011). From Mountain Man to Millionaire : the "Bold and Dashing Life" of Robert Campbell (Revised and expanded ed.). Columbia, Mo.: University of Missouri Press. pp. 6–11.

- ↑ Carter, p. 298

- ↑ Carter, pg. 300; Nester, 43-44

- ↑ Hardee, Jim (2010). Pierre's Hole! The Fur Trade History of Teton Valley, Idaho. Wyoming: Sublette County Historical Society. p. 158.

- ↑ Hardee, 182-183; 187-189; 203-212

- ↑ Nester, 75-104

- ↑ Nester, 106-112

- ↑ Nester, 120-128, 130; Campbell House Courier, "Did You Know?" Spring 2002, pg. 3

- ↑ Nester, 144-145; 150

- ↑ Nester, 173-184

- ↑ Nester, 148, 173-174

- ↑ Nadeau, Remi (1967). Fort Laramie and the Sioux Indians. Englewod Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc. pp. 66–82.

- ↑ Primm, James Neal (1998). Lion of the Valley: St. Louis, Missouri, 1764-1980 (3rd ed.). Missouri: Missouri Historical Society Press. p. 167.

- ↑ Campbell House Courier, "Important Research Projects Begin," Winter 2003

- ↑ Gerteis, Louis (2001). Civil War St. Louis. Kansas: University Press of Kansas. pp. 73, 81–82.

- ↑ Campbell House Courier, "Did Robert Campbell Own Slaves?" Fall 2010.

- ↑ Nester, 212, 228;"Robert Campbell Burned". St. Louis Daily Union. 15 Oct 1863.

- ↑ Gerteis, 115; Nester, 213-215

- ↑ Thomas Gronski, " 'A Very Troublesome Controversy'--Robert Campbell and the Growth of El Paso, Texas," Campbell House Courier, Fall 2013, 6-7; Gold Mining, Open Research File Drawer, Folder 8-1, Campbell House Museum.

- ↑ Nester, 237-238; Campbell House Courier, "The great Southern Hotel fire," Spring 2002, 2-3.

- ↑ Nester 243-245

- ↑ Nester, 249-251; "Obituary of Robert Campbell". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. February 2, 1879.

- ↑ Nester, 112-113; Lucy Kyle to Robert Campbell, Jan. 14, 1838, Deibel Collection, Campbell House Museum, 1999.8.35; Lucy Kyle to Robert Campbell, Feb. 3, 1838, Deibel Collection, Campbell House Museum 1999.8.38

- ↑ Robert Campbell to Virginia Kyle, July 5th, 1839, Deibel Collection, 1999.8.46; Lucy Kyle to Virginia Kyle, December 18, 1840, Missouri Historical Society; Virginia Campbell to Robert Campbell, February 5th, 1841, Deibel Collection, 1999.8.66.

- ↑ Nestor, 184; Robert Campbell to John Dougherty, July 21st 1849, Campbell House Museum Online Archive, campbellhouse.pastperfect-online.com/34842cgi/mweb.exe?request=record;id=FD1B19E0-E3D6-45D7-81C4-867823158558;type=301 (Accessed 19 September 2014).

- ↑ Thomas Gronski, “Lucas Place Encyclopedia, 10 July 2013,” (Campbell House Museum: Saint Louis, MO), 14-15; Records from Bellefontaine Cemetery, Open Research File Drawer, Campbell House Museum, Folder 2; Nester, 206.

- ↑ "Obituary of Robert Campbell". St. Louis Globe-Democrat. February 2, 1879.

- Carter, Harvey L. (1983). "Robert Campbell". In Leroy R. Hafen. Trappers of the Far West Sixteen Biographical Sketches. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 0-8032-7218-9.originally published in Leroy R. Hafen, ed. (1971). Mountain Men and Fur Traders of the Far West vol. VIII. Glendale: The Arthur H Clark Company.

- The Campbell House Museum Website

- Aughalane House

- Nester, William R. From Mountain Man to Millionaire: The ‘Bold and Dashing’ Life of Robert Campbell. Revised Edition. Columbia: University of Missouri Press, 2011.

- Buckley, Jay H. “Rocky Mountain Entrepreneur: Robert Campbell as a Fur Trade Capitalist.” Journal of the Wyoming Historical Society. Summer 2003. 8-23.

- Campbell, Robert. “The Rocky Mountain Letters of Robert Campbell.” The National Atlas and Tuesday Morning Mail. 1836. Republished 1955.

- Brooks, George R., editor. “The Private Journal of Robert Campbell.” Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society, Oct. 1963. 3-24. Jan. 1964. 107-118.

- Brooks, George R., editor. “Journal of Hugh Campbell.” Bulletin of the Missouri Historical Society. April 1967. 241-268.

- Primm, James Neal. Lion in the Valley: St. Louis, Missouri 1764-1980. Third Edition. St. Louis: Missouri Historical Society Press, 1998.

- Gerteis, Louis S. Civil War St. Louis. United States: University Press of Kansas, 2001.