Robben Island

| Robben Island Robbeneiland | |

|---|---|

|

Robben Island Village | |

Robben Island  Robben Island  Robben Island

| |

|

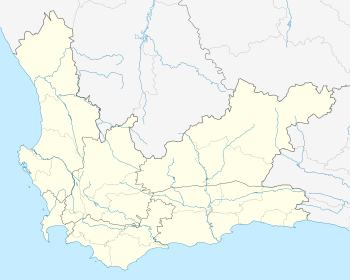

Location within Cape Town  Robben Island | |

| Coordinates: 33°48′24″S 18°21′58″E / 33.806734°S 18.366222°ECoordinates: 33°48′24″S 18°21′58″E / 33.806734°S 18.366222°E | |

| Country | South Africa |

| Province | Western Cape |

| Municipality | City of Cape Town |

| Area[1] | |

| • Total | 5.18 km2 (2.00 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 116 |

| • Density | 22/km2 (58/sq mi) |

| Racial makeup (2011)[1] | |

| • Black African | 60.3% |

| • Coloured | 23.3% |

| • White | 13.8% |

| • Other | 2.6% |

| First languages (2011)[1] | |

| • Xhosa | 37.9% |

| • Afrikaans | 35.3% |

| • Zulu | 15.5% |

| • English | 7.8% |

| • Other | 3.4% |

| PO box | 7400 |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | iii, vi |

| Designated | 1999 (23rd session) |

| Reference no. | 916 |

| State Party | South Africa |

| Region | Africa |

Robben Island (Afrikaans: Robbeneiland) is an island in Table Bay, 6.9 km west of the coast of Bloubergstrand, Cape Town, South Africa. The name is Dutch for "seal island." Robben Island is roughly oval in shape, 3.3 km long north-south, and 1.9 km wide, with an area of 5.07 km².[2] It is flat and only a few metres above sea level, as a result of an ancient erosion event. Nobel Laureate and former President of South Africa Nelson Mandela was imprisoned there for 18 of the 27 years he served behind bars before the fall of apartheid. To date, three of the former inmates of Robben Island have gone on to become President of South Africa: Nelson Mandela, Kgalema Motlanthe,[3] and current President Jacob Zuma.

Robben Island is both a South African National Heritage Site as well as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[4][5]

History

Since the end of the 17th century, Robben Island has been used for the isolation of mainly political prisoners. The Dutch settlers were the first to use Robben Island as a prison. Its first prisoner was probably Autshumato in the mid-17th century. Among its early permanent inhabitants were political leaders from various Dutch colonies, including Indonesia, and the leader of the mutiny on the slave ship Meermin.

After the British Royal Navy captured several Dutch East Indiamen at the battle of Saldanha Bay in 1781, a boat rowed out to meet the British warships. On board were the "kings of Ternate and Tidore, and the princes of the respective families". The Dutch had long held them on "Isle Robin", but then had moved them to Saldanha Bay.[6]

In 1806 the Scottish whaler John Murray opened a whaling station at a sheltered bay on the north-eastern shore of the island which became known as Murray's Bay, adjacent to the site of the present-day harbour named Murray's Bay Harbour which was constructed in 1939–40.[7][8]

After a failed uprising at Grahamstown in 1819, the fifth of the Xhosa Wars, the British colonial government sentenced African leader Makanda Nxele to life imprisonment on the island.[9] He drowned on the shores of Table Bay after escaping the prison.[10][11]

The island was also used as a leper colony and animal quarantine station.[12] Starting in 1845 lepers from the Hemel-en-Aarde (heaven and earth) leper colony near Caledon were moved to Robben Island when Hemel-en-Aarde was found unsuitable as a leper colony. Initially this was done on a voluntary basis and the lepers were free to leave the island if they so wished.[13] In April 1891 the cornerstones for 11 new buildings to house lepers were laid. After the introduction of the Leprosy Repression Act in May 1892 admission was no longer voluntary and the movement of the lepers was restricted. Prior to 1892 an average of about 25 lepers a year were admitted to Robben Island, but in 1892 that number rose to 338, and in 1893 a further 250 were admitted.[13]

During the Second World War the island was fortified and BL 9.2-inch guns and 6-inch guns were installed as part of the defences for Cape Town.

From 1961, Robben Island was used by the South African government as prison for political prisoners and convicted criminals from 1961. In 1969 the Moturu Kramat, which is now a sacred site for Muslim pilgrimage on Robben Island, was built to commemorate Sayed Abdurahman Moturu, the Prince of Madura. Moturu, who was one of Cape Town's first imams, was exiled to the island in the mid-1740s. He died there in 1754. Muslim political prisoners would pay homage at the shrine before leaving the island.

The maximum security prison for political prisoners closed in 1991. The medium security prison for criminal prisoners was closed five years later.[14]

With the end of apartheid, the island has become a popular destination with global tourists. It is managed by Robben Island Museum (RIM); which operates the site as a living museum. In 1999 the island was declared a World Heritage Site. Every year thousands of visitors take the ferry from the Victoria & Alfred Waterfront in Cape Town for tours of the island and its former prison. Many of the guides are former prisoners. All land on the island is owned by the state of South Africa with the exception of the island church. It is open all year around, weather permitting.

Maritime hazard

Seagoing vessels must take great care navigating near Robben Island and nearby Whale Rock (it does not break the surface) as they pose a danger to shipping.[15] A prevailing rough Atlantic swell surrounds the offshore reefs and the island's jagged coastline. Stricken vessels driven onto rocks are quickly broken up by the powerful surf. There are a total of 31 known vessels that have been wrecked around the island.[16]

In 1990, a marine archaeology team from the University of Cape Town began Operation "Sea Eagle". It was an underwater survey that scanned 9 square nautical miles of seabed around Robben Island. The task was made particularly difficult by the very sea conditions that make sailing in these waters treacherous: strong currents, high waves and rough conditions. Nevertheless, the group managed to find 24 vessels that had sank around Robben Island. Most wrecks were found in waters less than 10 metres (33 ft). The team concluded that poor weather, darkness and fog were the cause of the sinkings.[16]

Maritime wrecks around Robben Island and its surrounding waters include the 17th century Dutch East Indiaman ships, the Yeanger van Horne (1611), the Shaapejacht (1660), and the Dageraad (1694). Later 19th century wrecks include several British brigs including the Gondolier (1836) and the American clipper, A.H. Stevens (1866). In 1901 the mail steamer SS Tantallon Castle struck rocks off Robben Island in dense fog shortly after leaving Cape Town. After distress cannons were fired from the island, nearby vessels rushed to the rescue. All 120 passengers and crew were taken off the ship before it was broken apart in the relentless swell. A further 17 ships have been wrecked in the 20th century these include British, Spanish, Norwegian and Taiwanese vessels.

Robben Island lighthouse

Due to the maritime danger that Robben Island presents to shipping, Jan van Riebeeck, the first Dutch colonial administrator in Cape Town in the 1650s, ordered that huge bonfires were to be lit at night on top of Fire Hill, the highest point on the island (now Minto Hill). These were to warn VOC ships approaching the island.

In 1865 Robben Island lighthouse was completed on Minto Hill.[17] The cylindrical masonry tower, which has an attached lightkeepers house at its base, is 18 metres (59 ft) high with a lantern gallery at the top. In 1938 the lamp was converted to electricity. The lighthouse utilises a flashing lantern instead of a revolving lamp; it shines for a duration of 5 seconds every seven seconds. The 46,000 candela beam flashes white light away from Table bay. It is visible up to 24 nautical miles (28 mi).[18] A secondary red light acts as a navigation aid for vessels sailing south southeast.

Wildlife and conservation

When the Dutch arrived in the area in 1652, the only large animals on the island were seals and birds, principally penguins. In 1654, the settlers released rabbits on the island to provide a ready source of meat for passing ships.[19]

The original colony of African penguins on the island was completely exterminated by 1800. However the modern day island is once again an important breeding area for the species after a new colony established itself there in 1983.[20] The colony grew to a size of ~16,000 individuals in 2004, before starting to decline in size again. As of 2015, this decline has been continuous (to a colony size of ~3,000 individuals) and mirrors that found at almost all other African penguin colonies. Its causes are still largely unclear and likely to vary between colonies, but at Robben Island are probably related to a diminishing of the food supply (sardines and anchovies) through competition by fisheries.[21] The penguins are easy to see close up in their natural habitat and are therefore a popular tourist attraction.

Around 1958, Lieutenant Peter Klerck, a naval officer serving on the island, introduced various animals. The following extract of an article, written by Michael Klerck who lived on the island from an early age, describes the fauna life there:[22]

My father, a naval officer at the time, with the sanction of Doctor Hey, director of Nature Conservation, turned an area into a nature reserve. A 'Noah's Ark' berthed in the harbour sometime in 1958. They stocked the island with tortoise, duck, geese, buck (which included Springbok, Eland, Steenbok, Bontebok and Fallow Deer), Ostrich and a few Wildebeest which did not last long. All except the fallow deer are indigenous to the Cape. Many animals are still there[23] including three species of tortoise—the most recently discovered in 1998—two Parrot Beaked specimens that have remained undetected until now. The leopard or mountain tortoises might have suspected the past terror; perhaps they had no intention of being a part of a future infamy, but they often attempted the swim back to the mainland (they are the only species in the world that can swim). Boats would lift them out of the sea in Table Bay and return them to us. None of the original 12 shipped over remain, and in 1995, four more were introduced—they seem to have more easily accepted their home as they are still residents. One resident brought across a large leopard tortoise discovered in a friend's garden in Newlands, Cape Town. He lived in our garden and grew big enough to climb over the wall and roam the island much like the sheep in Van Riebeeck's time. As children we were able to ride his great frame comfortably, as did some grown men. The buck and ostriches seemed equally happy and the ducks and Egyptian Geese were assigned a home in the old quarry, which had, some three hundred years before, supplied the dressed stone for the foundations of the Castle; at the time of my residence it bristled with fish. It has also been mentioned in Pointless. Recent reports in Cape Town newspapers show that a lack of upkeep, a lack of culling, and the proliferation of rabbits on the island has led to the total devastation of the wildlife; there remains today almost none of the animals my father brought over all those years ago; the rabbits themselves have laid the island waste, stripping it of almost all ground vegetation. It looks almost like a desert. A reporter from the broadcasting corporation told me recently that they found the carcass of the last Bontebok.

There may be 25,000 rabbits on the island. Humans are hunting and culling the rabbits to reduce their number.[24]

List of former prisoners held at Robben Island

- Autshumato, one of the first activists against colonialism

- Dennis Brutus, former activist and poet

- Patrick Chamusso, former activist of the African National Congress

- Laloo Chiba, former accused at Little Rivonia Trial

- Eddie Daniels (political activist)

- Jerry Ekandjo, Namibian politician

- Nceba Faku, former Metro Mayor of Port Elizabeth

- Petrus Iilonga, Namibian trade unionist, activist and politician

- Ahmed Kathrada, former Rivonia Trialist and long-serving prisoner

- Koesaaij, Malagasy co-leader of the Meermin slave mutiny in February, 1766

- Langalibalele, The King of the Hlubi people, one of the first activists against colonialism

- John Kenneth Malatji, former activist and special forces of ANC - Tladi, Soweto

- Njongonkulu Ndungane,[25] later to become Archbishop of Cape Town

- Mosiuoa Lekota, imprisoned in 1974, President and Leader of the Congress of the People

- Mac Maharaj, former accused at Little Rivonia Trial

- Makana, one of the activists against colonialism

- Nelson Mandela, African National Congress leader and former President of South Africa (first black president)

- Gamzo Mandierd, activist

- Jeff Masemola, the first prisoner sentenced to life imprisonment in the apartheid era

- Amos Masondo, former Mayor of Johannesburg

- Massavana, Malagasy leader of the Meermin slave mutiny in February, 1766

- Michael Matsobane, leader of Young African Religious Movement. Sentenced at Bethal in 1979; released by PW Botha in 1987.

- Chief Maqoma, former chief who died on the island in 1873

- Govan Mbeki, father of former President of South Africa Thabo Mbeki. Govan was sentenced to life in 1963 but was released from Robben Island in 1987 by PW Botha

- Wilton Mkwayi, former accused at Little Rivonia Trial

- Murphy Morobe, Soweto Uprising student leader

- Dikgang Moseneke, Deputy Chief Justice of South Africa

- Sayed Adurohman Moturu, the Muslim Iman who was exiled on the island and died there in 1754

- Griffiths Mxenge, a South African Lawyer and member of the African National Congress

- Billy Nair, former Rivonia Trialist and ANC/SACP leader

- M. D. Naidoo, a South African lawyer and member of the African National Congress

- John ya Otto Nankudhu, Namibian liberation fighter[26]

- John Nkosi Serving life but released by PW Botha in 1987

- Nongqawuse, the Xhosa prophetess responsible for the Cattle Killing

- Maqana Nxele, former Xhosa prophet who drowned while trying to escape

- John Nyathi Pokela, co-founder and former chairman of the PAC

- Joe Seremane, current chairperson of the Democratic Alliance.

- Tokyo Sexwale, businessman and aspirant leader of the African National Congress

- Gaus Shikomba, Namibian politician

- Walter Sisulu, former ANC Activist

- Stone Sizani, ANC Chief Whip

- Robert Sobukwe, former leader of the PAC

- Andimba Toivo ya Toivo, Namibian politician

- Jacob Zuma, President of South Africa and leader of the African National Congress

- Achmad Cassiem

- Setsiba Paul Mohohlo, former APLA unit commander

- Micheal Ludumo Buka, former ANC Activist

- Kgalema Motlanthe, South Africa's first Pedi president

- John Aifheli Thabo, an ANC political activist

- Ezra Mvuyisi Sigwela, an ANC political activist

- Oliver Tambo, longest-serving ANC president

References

- 1 2 3 4 "Main Place Robben Island". Census 2011.

- ↑ "Avian Demography Unit: Robben Island". Department of Biological Sciences, University of Cape Town.

- ↑ "New S. Africa president sworn in". BBC News. 25 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-11-22.

- ↑ "9/2/018/0004 - Robben Island, Table Bay". South African Heritage Resources Agency. Retrieved 16 September 2013.

- ↑ "Robben Island". UNESCO. Retrieved 2 June 2011.

- ↑ The New Annual Register, Or General Repository of History ..., (October 1781), Vol. 2, p.90.

- ↑ Peires, Jeffrey B. (1989). The Dead Will Arise: Nongqawuse and the Great Xhosa Cattle Killing Movement of 1856–7. Indiana University Press. p. 301. ISBN 9780253205247.

- ↑ Deacon, Harriet, ed. (1996). The Island: A History of Robben Island, 1488–1990. New Africa Books. pp. 4–5. ISBN 9780864862990.

- ↑ Frederick Marryat. The Mission; or Scenes in Africa. London: Nick Hodson. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- ↑ "Christianity in Africa South of the Sahara: 19th Century Xhosa Christianity". Bethel University. Archived from the original on 14 May 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- ↑ Edwin Diale (1979). "Makana". African National Congress. Archived from the original on 2 June 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- ↑ Winston Churchill (1900). London to Ladysmith via Pretoria. London: Longmans, Green, and Co. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- 1 2 Newman, George (1895). Prize essays on leprosy. London: The Society. p. 194.

- ↑ Chronology, Robben Island Museum website, retrieved 8 June 2013

- ↑ James Horsburgh (1852). The India Directory, Or Directions for Sailing to and from the East Indies, China, Australia and the Interjacent Ports. W. H. Allen & Co. p. 71.

- 1 2 Smith, Charlene (1997). Robben Island. Struik. pp. 30–32. ISBN 9781868720620.

- ↑ William Henry Rosser, James Frederick Imray (1867). The Seaman's Guide to the Navigation of the Indian Ocean and China Sea. J. Imray & Son. p. 280. Retrieved 2008-10-04.

- ↑ "Robben Island Lighthouse". Retrieved 29 October 2014.

- ↑ George McCall Theal (1897). History of South Africa Under the Administration of the Dutch East India Company (1652 to 1795). Swan Sonnenschein. p. 442. Retrieved 2008-10-10.

- ↑ Les Underhill. "Robben Island". Avian Demography Unit, University of Cape Town. Retrieved 2008-10-12.

- ↑ Weller, F.; Cecchini, L.A.; Shannon, L.; Sherley, R.B.; Crawford, R.J.; Altwegg, R.; Scott, L.; Stewart, T.; Jarre, A. (2014). "A system dynamics approach to modelling multiple drivers of the African penguin population on Robben Island, South Africa". Ecological Modelling. 277: 38–56. doi:10.1016/j.ecolmodel.2014.01.013.

- ↑ Michael Klerck. "Robben Island: Childhood Memories—a personal reflection". www.robbenisland.org. Retrieved 2008-11-23.

- ↑ No longer true as of 2008

- ↑ BBC News. Robben Island is 'under threat'. 31 October 2009.

- ↑ Sindiwe Magona (1 October 2012). From Robben Island to Bishop's Court: The Biography of Archbishop Njongonkulu Ndungane. David Philip. ISBN 978-0-86486-738-4.

- ↑ "John Ya Otto Nankudhu passes on". New Era. NAMPA. 22 June 2011.

Further reading

- Weideman, Marinda (June 2004). "ROBBEN ISLAND'S ROLE IN COASTAL DEFENCE, 1931–1960". Military History Journal: The South African Military History Society. 13 (1). Retrieved 17 September 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Robben Island. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Robben Island. |

- Robben Island Museum

- Robben Island – UNESCO World Heritage Centre

- Robben Island Museum at Google Cultural Institute

.jpg)

.jpg)