Right hemisphere brain damage

| Right hemisphere brain damage | |

|---|---|

|

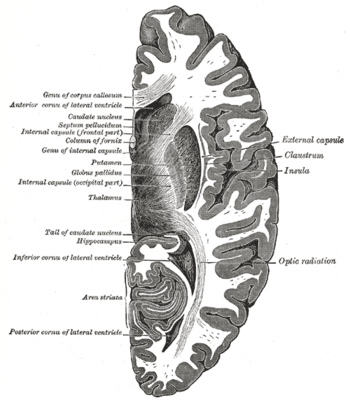

Horizontal section of right cerebral hemisphere. |

Right hemisphere brain damage (RHD) is the result of injury to the right brain hemisphere.[1] The right hemisphere of the brain coordinates tasks for functional communication, which include problem solving, memory, and reasoning.[1] Deficits caused by right hemisphere brain damage vary depending on the location of the damage.[2]

Signs and symptoms

Cognitive and communicative

Patients with right hemisphere brain damage most commonly have difficulties with attention, perception, learning, memory, recognition and expression of emotion, and neglect.[3] Other frequently occurring, though slightly less common, deficits include reasoning and problem solving, awareness, and orientation.[3] It is also common for patients with right hemisphere damage to have a flat affect, lack of emotional expression, while speaking. Additionally, these patients commonly have difficulty recognizing other people's emotions when expressed through facial expressions and tone of voice.[2] Although these deficits alone may complicate therapy, the patient may also exhibit anosognosia, or ignorance of his or her impairments.[4][5] Due to possible anosognosia, it is common for patients to not become frustrated or upset when they are unable to complete tasks they were previously able to complete.[6]

Difficulties with communication are likely to be linked to a patient's cognitive deficits. For example, communication breakdown may result because a patient with right hemisphere brain damage fails to observe appropriate social conventions or because the patient may ramble and fail to recognize appropriate times to take conversational turns.[2] The patient may also have difficulty comprehending sarcasm, irony, and other paralinguistic aspects of communication.[7] Additionally, individuals with right hemisphere brain damage may have impaired advanced language abilities such as narrative skills.[6] Patients may find it difficult to extract the theme of a story, or arrange sentences based on the theme of a story.[8]

Motor and sensory

A frequently occurring motor deficit is left-sided hemiparesis (in strokes affecting the motor cortex). A less common motor deficit in this population is dysphagia.[3]

Patients with right hemisphere brain damage often display sensory deficits such as left neglect, in which they ignore everything in the left visual field.[4] This neglect can be present throughout many daily activities including reading, writing and self-care activities.[2] For example, individuals with left neglect typically leave out details on the neglected side of drawings or try to draw out all the details on the nonneglected side.[9] Homonymous hemianopsia is another sensory deficit that is sometimes observed in this population.[3]

Cause

Stroke is the most common source of damage for a right hemisphere damage. The stroke for this disorder occurs in the right hemisphere of the brain. Other etiologies that cause right hemisphere damage include: trauma (traumatic brain injury), disease, seizures disorders, and infections. Depending on the etiology that causes the right hemisphere damage, different deficits can be accounted for.[10] "The level of deficit or disorder an individual with right hemisphere damage displays depends on the location and extent of the damage. A small focal right hemisphere stroke can produce a very specific deficit and leave most other cognitive and perceptual processes intact, whereas a very large stroke in the right hemisphere more than likely results in multiple profound deficits.[11]" Adults with right hemisphere damage may exhibit behavior that can be characterized by insensitivity to others and preoccupation with self; unawareness of the social context of conversations; and verbose, rambling and tangential speech.[12]

Diagnosis

Right hemisphere brain damage is diagnosed by a medical professional. Computerized tomography (CT) scans and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are often used to determine where the damage occurred and how severe it is (ASHA).[13]

Standardized assessments are used by speech-language pathologists to determine the presence and severity of right hemisphere brain damage. The three most popular standardized assessments include:

- The Mini Inventory of Right Brain Injury - Second Edition (MIRBI -2) - a standardized test that can be used to identify the presence, severity, and identify the patient's strengths and weaknesses.

- The Right Hemisphere Language Battery - Second Edition, (RHLB-2) -a comprehensive test battery for evaluation of right hemisphere-injured adults.

- The Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago Evaluation of Communicative Problems in Right-Hemisphere Dysfunction Revised (RICE-R) -includes nine subtests which include a patient interview and ratings of facial and written expression and severity ratings for each subtest.[2]

Non-standardized tests can also be useful in determining the communicative deficits of adults with right-hemisphere brain damage. Those procedures include tests of: Visual and Spatial Perception, Attention, and Organization, Component Attentional Processes and Visual Organization. [Do the previously listed “tests” need to be capitalized?] Other non-standardized tests that can be used include:

- The Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Exam (BDAE)-Auditory comprehension, oral expression, and reading subtests

- The Revised Token Test

- The Boston Naming Test

- The Word Fluency Test.[2]

Treatment

Treatment for right hemisphere damage is given by speech-language pathologists. There is not much research that has been done regarding the efficacy of treatments for right hemisphere damage. The research that has been done has shown that persons with right hemisphere damage benefit from therapy at both the chronic and acute stages of recovery for language.[14] Research has also shown that treatment given by speech-language pathologists to persons with right hemisphere damage results in improvement in the areas of problem solving, attention, memory, and pragmatics.[15]

Different treatment approaches can be used to treat the different symptoms of right hemisphere damage including neglect, visuospatial awareness, prosody, and pragmatics. Therapy for each person is individualized to their symptoms and severity of impairment. Intervention should focus on the needs of the person in both communication and functional aspects.

Data from the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association (ASHA) indicate that treatment for individuals with right hemisphere damage tends to focus on areas other than communication, including swallowing, memory, and problem solving. Deficits in language expression, language comprehension, and pragmatics are addressed much less frequently (in 22%, 23%, and 5% of individuals, respectively).[16] The lack of research focusing on communication treatment is cited as a possible explanation for these low percentages.[14] Small-scale and pilot studies have been conducted in recent years to fill the identified gaps in the treatment literature. Emerging evidence is discussed below.

Prosody

Right hemisphere damage can lead to aprosodia—the inability to produce or comprehend emotional prosody of language. Emotional prosody is typically conveyed and interpreted through changes in pitch, rhythm, or loudness (Leon et al., 2005).[17] Research thus far has focused primarily on motoric-imitative and cognitive-linguistic approaches to prosody treatment. In a motoric-imitative approach, the client imitates clinician-modeled sentences produced with target emotional prosody. Modeling and cueing is gradually reduced following a six-step hierarchy until the client reaches independent production. In the cognitive-linguistic approach, the client is prompted to produce sentences with the support of cue cards. Cues include the name of the target emotion, the vocal characteristics of the emotional tone, and a picture of a corresponding facial expression. Again, cues are gradually removed as the client progresses toward independent production.[18] Clinical studies of small groups of participants (four participants;[17] 14 participants.[18]) revealed statistically significant gains in the production of emotional prosody following treatment. Additional research is needed to replicate the results of the limited studies that have been conducted thus far, to evaluate the efficacy of additional treatment approaches, and to compare the relative efficacy of different approaches.[14][19]

Outcome

Right hemisphere damage can lead to deficits in discourse abilities, including difficulty with interpretation of abstract language, making inferences, and understanding nonverbal cues.[14][19] In particular, individuals with right hemisphere damage struggle with the skilled use of context to interpret and express ideas.[19] A study of five participants with right hemisphere damage found that participants’ ability to orally interpret metaphors was statistically significantly improved following a five-week structured training intervention. The training program included five phases focused on facilitating the use of word meanings and semantic associations to increase participants’ understanding of metaphors.[20] Another study of three participants found that a contextual stimulation treatment increased participants’ ability to efficiently activate distantly associated meanings and to suppress contextually inappropriate meanings.[21] Again, additional research is needed to replicate and extend results, but the emerging literature represents a small step toward evidence-based treatments for right hemisphere damage.[14]

Prognosis

Sex

Research has indicated that women are more likely to be left hemisphere dominant, and men are more likely to be right hemisphere dominant. Because of this, women recover faster from left hemisphere damage, and men are more likely to recover faster from right hemisphere damage. Men who have suffered a right hemisphere stroke also have significantly better rehabilitation outcomes than men who suffer a left hemisphere stroke. Recovery of functional abilities is often greater in male stroke survivors than females, especially in the area of activities of daily living.[22]

Neglect

Left neglect is common in patients recovering from right hemisphere damage. The presence and severity of neglect has been shown to influence functional outcomes as well as length of rehabilitation after a stroke.

Patients with neglect for peripersonal space (space within reach), are likely to recover most during the first 10 days after a stroke, but further improvements from 6 months to 1 year post onset are unlikely. However, the prognosis for patients with neglect for personal body space or neglect for far space is much better. These types of neglect are more likely to recover completely or almost completely after 6 months post onset. Although there may be some lasting effects of neglect of varying degrees based on the type, many patients with neglect are likely to improve over time (Appelros et al., 2004).[23]

Functional outcomes

The Functional Independence Measure (FIM) is often used to determine the functional skills a patient has at various times after their brain damage. Research has indicated that patients with more severe neglect are less likely to make functional improvements than patients with less severe neglect based on FIM scores. Additionally, patients with any level of neglect tend to have reduced functional cognitive and communication skills than patients without neglect (Cherney et al., 2001).[24]

Rehabilitation

Patients with neglect have been shown to need rehabilitation longer than patients who suffered from right hemisphere damage that did not result in neglect. On average, patients with neglect stayed in inpatient rehabilitation facilities one week longer, and this length of stay did not differ for patients with more or less severe neglect (Cherney et al., 2001).[24]

Anosognosia

Anosognosia is a lack of awareness or understanding of the loss of function caused by the brain injury and is common in individuals who have suffered a right hemisphere stroke. Because patients with anosognosia may be unaware of their deficits, they may be less likely to seek treatment once they are released from the hospital. The lack of proper treatment could lead to higher levels of dependency later on. In order to make functional recovery gains, right hemisphere stroke survivors should receive rehabilitation services, so patients with anosognosia should be encouraged to seek out additional treatment. However, due to the anosognosia, these patients often report a higher perceived quality of life than other right hemisphere stroke survivors because of the unawareness of the resulting deficits (Daia et al., 2014).[25] Patients with smaller lesions often recover faster from anosognosia than patients with larger lesions resulting in anosognosia (Hier et al., 1983).[26]

Other influences

Age: Younger patients typically recover faster than older patients, especially with regards to prosopagnosia (difficulty recognizing faces)

Size of lesion: Patients with smaller lesions typically recover faster from neglect and hemiparesis (unilateral body weakness) than patients with larger lesions (Hier et al., 1983).[26]

History

For the majority of the nineteenth century, the left brain hemisphere was the key focus of clinical research on language disorders (Brookshire, 2007).[2] In the twentieth century, focus gradually shifted to include right hemisphere damage (Brookshire, 2007).[2] It is now well established that language and cognition can be seriously impaired by unilateral right hemisphere brain damage.[27] Specific cognitive tests can help diagnose the existence of right hemisphere brain damage and differentiate symptoms from those of left hemisphere damage.[28] Unlike the aphasias, caused by left hemisphere damage and generally resulting in focused language deficits, right hemisphere brain damage can result in a variety of diffuse deficits which complicate formal testing of this disorder (Brookshire, 2007).[2] These formal tests assess areas such as understanding humor, metaphors, sarcasm, facial expression, and prosody.[10] However, not all individuals with right hemisphere brain damage have problems in language or communication and some may have no discernible symptoms.[27] Indeed, about half of patients with right hemisphere damage have intact communication abilities (Brookshire, 2007).[2][29]

See also

References

- 1 2 American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2015). Right hemisphere brain damage. Retrieved from http://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/RightBrainDamage/

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Brookshire, R. H. (2007). Right hemisphere syndrome. In K. Falk (Ed.), Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders (7th ed., pp. 391-443). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

- 1 2 3 4 Lehman Blake M., Duffy J. R., Myers P. S., Tompkins C. A. (2002). "Prevalence and patterns of right hemisphere cognitive/communicative deficits: Retrospective data from an inpatient rehabilitation unit". Aphasiology. 16: 537–547. doi:10.1080/02687030244000194.

- 1 2 Klonoff P. S., Sheperd J. C., O'Brien K. P., Chiapello D. A., Hodak J. A. (1990). "Rehabilitation and outcome of right-hemisphere stroke patients: Challenges to traditional diagnostic and treatment methods". Neuropsychology. 4: 147–163. doi:10.1037/0894-4105.4.3.147.

- ↑ Orfei M. D., Robinson R. G., Prigatano G. P., Starkstein S., Rüsche N., Bria P., Spalletta G. (2007). "Anosognosia for hemiplegia after stroke is a multifaceted phenomenon: A systematic review of the literature". Brain. 130: 3075–3090. doi:10.1093/brain/awm106.

- 1 2 Benowitz L., Moya K., Levine D. (1989). "Impaired verbal reasoning and constructional apraxia in subjects with right hemisphere brain damage". Neuropsychologia. 28: 231–241. doi:10.1016/0028-3932(90)90017-i.

- ↑ Handbook of the neuroscience of language by Brigitte Stemmer 2008 ISBN 0-08-045352-X page 205

- ↑ Cognitive Neuroscience by Marie T. Banich, Rebecca J. Compton 2010 ISBN 0-8400-3298-6 page 262

- ↑ Manasco, M. H. (2014). Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- 1 2 Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders by Hunter Manasco 2014 ISBN 9781449652449

- ↑ Manasco, H. (2014). The Aphasias. In Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders (Vol. 1, p. 91). Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

- ↑ Introduction to neurogenic communication disorders by Robert H. Brookshire 2007 ISBN 0-323-04531-6 page 393

- ↑ American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2015). Stroke. Retrieved from http://www.asha.org/public/speech/disorders/Stroke/

- 1 2 3 4 5 Blake M. L., Frymark T., Venedictov R. (2013). "An Evidence-Based Systematic Review on Communication Treatments for Individuals With Right Hemisphere Brain Damage". American Journal Of Speech-Language Pathology. 22 (1): 146–160.

- ↑ Blake, M. L. & Tomkins, C. A. (n.d.). Cognitive-communication disorders resulting from right hemisphere brain damage. American Speech and Language Association. Retrieved from http://www.asha.org/uploadedFiles/public/TESCognitiveCommunicationDisordersfromRightHemisphereBrainDamage.pdf

- ↑ American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. (2011). Data and research: Data outcomes [Analysis from ASHA NOMS database]. Rockville, MD: Author. Retrieved from www.asha.org/members/research/NOMS/default.htm

- 1 2 Leon S. A., Rosenbek J. C., Crucian G. P., Hieber B., Holiway B., Rodrigues A. D., Ketterson T. U., Ciampitti M. Z., Freshwater S., Heilman K., Gonza , Rothi L. (2005). "Active treatments for aprosodia secondary to right hemisphere stroke". Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 42 (1): 93–102.

- 1 2 Rosenbek J., Rodrigues A., Hieber B., Leon S., Crucian G., Ketterson T., Gonzalez-Rothi L. (2006). "Effects of two treatments for aprosidia secondary to acquired brain injury". Journal of Rehabilitation Research and Development. 43: 379–390. doi:10.1682/jrrd.2005.01.0029.

- 1 2 3 Blake M. L. (2007). "Perspectives on treatment for communication deficits associated with right hemisphere brain damage". American Journal Of Speech-Language Pathology. 16 (4): 331–342. doi:10.1044/1058-0360(2007/037).

- ↑ Lundgren K., Brownell H., Cayer-Meade C., Milione J., Kearns K. (2011). "Treating metaphor interpretation deficits subsequent to right hemisphere brain damage: Preliminary results". Aphasiology. 25: 456–474. doi:10.1080/02687038.2010.500809.

- ↑ Tompkins C., Blake M. T., Wambaugh J., Meigh K. (2011). "A novel, implicit treatment for language comprehension processes in right hemisphere brain damage: Phase I data". Aphasiology. 25: 789–799. doi:10.1080/02687038.2010.539784.

- ↑ Drake S (2012). "Gender and stroke lateralization: Factors of functional recovery after the first-ever unilateral stroke?". NeuroRehabilitation. 30: 247–254. doi:10.3233/NRE-2012-0752.

- ↑ Appelros P., Nydevik I., Karlsson G., Thorwalls A., Seiger A. (2004). "Recovery from unilateral neglect after right-hemisphere stroke". Disability and Rehabilitation. 26 (8): 471–477. doi:10.1080/09638280410001663058.

- 1 2 Cherney L., Halper A., Kwasnica C., Harvey R., Zhang M. (2001). "Recovery of functional status after right hemisphere stroke: Relationship with unilateral neglect". Archivesof Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation. 82 (3): 322–328. doi:10.1053/apmr.2001.21511.

- ↑ Data C. Y., Liua W. M., Chena S. W., Yangb C.-A., Tunga Y. C., Chouc L. W., Lind L. C. (2014). "Anosognosia, neglect and quality of life of right hemisphere stroke survivors". European Journal of Neurology. 21: 797–801. doi:10.1111/ene.12413''.

- 1 2 Hier D., Mondlock J., Caplan L. (1983). "Recovery of behavioral abnormalities after right hemisphere stroke". Neurology. 33 (3): 345–350. doi:10.1212/WNL.33.3.345.

- 1 2 The MIT encyclopedia of communication disorders by Raymond D. Kent 2003 ISBN 0-262-11278-7 page 388

- ↑ Cognition, Brain, and Consciousness: Introduction to Cognitive Neuroscience by Bernard J. Baars, Nicole M. Gage 2010 ISBN 0-12-375070-9 page 504

- ↑ Manasco, M. Hunter. Introduction to Neurogenic Communication Disorders. p. 106. ISBN 9781449652449.