Rosy bitterling

| Rosy bitterling | |

|---|---|

| | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Cypriniformes |

| Family: | Cyprinidae |

| Genus: | Rhodeus |

| Species: | R. ocellatus |

| Binomial name | |

| Rhodeus ocellatus (Kner, 1866) | |

| Synonyms | |

| |

The rosy bitterling (Rhodeus ocellatus) is a small freshwater fish belonging to the family Cyprinidae (carp). Females are about 40-50 mm long and males are 50-80 mm. Their bodies are flat with an argent-colored luster. However, males change to a reddish (sometimes purple) color during the spawning season (March to September) which functions to attract females. This reddish color is similar to the color of a red rose, which is why it is called a rosy bitterling.[1]

Ecology and reproductive system

Rosy bitterlings live in ponds (reservoirs) where freshwater mussels are abundant. Farm ponds are an important habitat for not only rosy bitterlings, but also mussels and plankton. Freshwater mussels play an important role in rosy bitterling reproduction. The female rosy bitterling has a unique pipe about the same length as its own body, used for laying eggs on a specific spot of mussels. Usually, two or three eggs are laid at once and placed on the gill of the mussel. A male spawns into the gill cavity of the mussels right after a female lays eggs to ensure fertilization.[2] Normally, a female lays eggs repeatedly at 6- to 9-day intervals about 10 times in a season.

Eggs grow in the mussels' gills and juveniles stay inside the mussel about 15 to 30 days after fertilization. Eggs hatch after about three days when juveniles are about 2.8 mm long. The body has a unique shape resembling the bud of a matsutake mushroom. Juveniles swim out of the mussel from the margin of the excurrent siphon. At this point, juveniles are about 7.5 mm long and about the same shape as adults.[3] Usually, juveniles grow around 40–50 mm within one year, when they become adults. R. o. kurumeus (Nippon baratanago) lives about three years and rarely exceeds this lifespan.[4]

Formerly recognized subspecies

(Nippon baratanago sex M)

(Tairiku baratanago sex M)

.jpg)

(Tairiku baratanago sex F)

Two subspecies have been recognized until recently; they are now considered conspecific.[5] R. o. kurumeus, which is used to be called R. o. smithi (Nippon baratanago) is a Japanese native species, but R. o. ocellatus (Tairiku baratanago) is found in China and Taiwan, as well as in Japan. The Nippon baratanago was widespread in the west side of Japan (Kyushu and western part of Honshū) before World War II. In 1942, the Tairiku baratanago was accidentally introduced with grass (Ctenopharyngodon idellus) and silver carp (Hypophthalmichthys molitrix) from mainland China to Japan.[6]

These two subspecies are morphologically very similar, but several distinguishing characters are seen, such as the number of longitudinal scales, principal rays in the dorsal and anal fins, and shape of eggs. Also, R. o. ocellatus has a silvery-white area anteriorly (white lines) on the ventral fin, but R. o. kurumeus does not. In comparison, the ventral fin of R. o. kurumeus is a dark color.[7] Another notable difference is body size. R. o. kurumeus does not commonly exceed 60 mm in length, whereas males of R. O. ocellatus are larger than 80 mm and females of this subspecies commonly exceed 60 mm.[8]

Status

The Nippon baratanago was widely distributed in small ponds, reservoirs, and creeks in Kyushu and the western part of Japan. However, since the Tairiku baratanago was introduced, their population has been increasing dramatically all over Japan. These two species coexist in many areas, and hybridization tends to occur easily.

| R. o. kurumeus

(Nippon Baratanago) | |

|---|---|

| Scientific classification | |

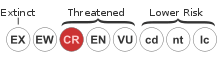

Hybridization and subsequent gene introgression has been observed within these subspecies in Kashima and Ogori.[9] Because of these interbreeding events, the number of R.o. kurumeus has dramatically declined all over Japan and now is in danger of extinction. In 1994, R. o. kurumeus (R. o. smithi, Nippon baratanago) was on the IUCN Red List as an endangered species, and now it is critically endangered. Nippon baratanago is also listed as a critically endangered species in the Japanese Red Data Book.[10]

Conservation

Environmental pollution, reservoir conditions, etc. have propagated the decline of native Japanese Rosy bitterlings in various places. Also, because the numbers of black bass and bluegills increase in such places, the amount of food availability for rosy bitterling declines.

Since R. o. kurumeus is critically endangered, nonprofit organizations and study groups were established in Japan to help protect this subspecies.

Yao study group, one of the Japanese rose bittering conservation groups, started activities for protecting endangered Nippon baratanago. For example, this organization (Yao City, Osaka) made the protection pond in May 1999 where 41 male and 60 female Nippon baratanago were released with prawns. Also, 45 freshwater mussels were transplanted at the same time. They monitored and collected data regularly through 2001. In 2000, they succeeded in increasing the Nippon baratanago population to 6000 individuals and they transferred 500 individuals to another five ponds from the protected pond. However, in 2001, few individuals were collected. Due to the poor water quality that year compared to previous years, the study group concluded eutrophication has a negative effect on reproduction in the rosy bitterling. Since then, Yao study group has considered designing new purification systems to conserve Japanese native rosy bitterlings. They also educate children (as an environmental study) for the next generation.[11]

References

- ↑ 加納義彦. ニッポンバラタナゴの保護と環境保全. 第5回日本水大賞受賞活動集. 日本水大賞顕彰制度委員会. 42-45. 2003.

- ↑ Kanoh, Y. 2000. Reproductive success associated with territoriality, sneaking, and grouping in male Rosy Bitterlings, Rhodeus ocellatus (Pisces: Cyprinidae). Env. Biol. Fish. 57: 143-154

- ↑ Nagata, Y. 1976. Reproductive behavior of a bitterling, Rhodeus ocellatus (Kner). Physiol. Ecol. Japan 17: 85-90 (in Japanese)

- ↑ Kimura, S., and Nagata, Y. 1992. Scientific name of Nipponbaratanago, Japanese bitterling of the genus Rhodeus. Japan.J.Ichthyol. 38: 425-429

- ↑ Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2014). "Rhodeus ocellatus" in FishBase. February 2014 version.

- ↑ Kawamura, K., Nagata, Y., Ohtaka, H., Kanoh, Y., and Kitamura, J. 2001. Genetic diversity in the Japanese rosy bitterling, Rhodeus ocellatus kurumeus (Cyprinidae). Ichthyol Res 48: 369-378

- ↑ Nagata, Y., T. Tetsukawa, T. Kobayashi and K. Numachi. 1996. Genetic markers distinguishing between the two subspecies of the rosy bitterling, Rhodeus ocellatus(Cyprinidae). Japan. J. Ichthyol. 43: 117-124

- ↑ Kimura, S., and Nagata, Y. 1992. Scientific name of Nippon baratanago, Japanese bitterling of the genus Rhodeus. Japan.J.Ichthyol. 38: 425-429

- ↑ Miyake, K., Tachida, H., Oshima, Y., Arai, R., Kimura, S., Imada, N., and Honjo, T. 2000. Genetic variation of the cytochrome b gene in the rosy bitterling, Rhodeus ocellatus (Cyprinidae) in Japan. Ichthyol Res 48: 105-110

- ↑ Kawamura, K., Nagata, Y., Ohtaka, H., Kanoh, Y., and Kitamura, J. 2001. Genetic diversity in the Japanese rosy bitterling, Rhodeus ocellatus kurumeus (Cyprinidae). Ichthyol Res 48: 369-378

- ↑ Kanoh, Y., Yoshinaka, T., Takemoto, Y., Iwasaki, and Y., Nishino, T. (Yao study group of Japanese rose bitterling) 2002. Conservation of Japanese rose bitterling Rhodeus ocellatus kurumeus. (in Japanese) 第11期 プロ・ナトゥーラ・ファンド助成成果報告書

External links

- Genetic markers distinguishing between the two subspecies of the rosy bitterling, Rhodeus ocellatus (Cyprinidae)

- "Rhodeus ocellatus". Integrated Taxonomic Information System.

- Tazonomy summary for R. o. kurumeus

- Taxonomy summary for R. o. ocellatus

- IUCN Red List

- Japanese Red List Data 日本環境庁(現・環境省)レッドリスト

- Conservation of Nippon baratanago 香川淡水魚研究会

- Conservation of Nippon baratanago and its environment ニッポンバラタナゴの保護と環境保全

Photo links

- Conservation of Nippon Baratanago and its Environment ニッポンバラタナゴの保護と環境保全

- Photo of Nippon Baratanago 日本バラタナゴ専門

- Photo of Tairiku Baratanago タイリクバラタナゴ専門]

]