Workplace respirator testing

To protect workers from air contaminants employers often used respirators. Reliable protection of workers' life and health requires that the effectiveness of the respirator must be consistent with the degree of air pollution. There are respiratory protective equipment RPE (or devices - RPD) of different designs, and their protective properties differ markedly. If employer wish to select the appropriate respirator, he or she need to know in advance what level of protection it will provide.

Initially, the effectiveness of respirators were evaluated with their tests in the laboratories. But detection of cases of excessive exposure of harmful agents on those workers who properly used and maintained approved respirators (with high efficiency filters), has prompted experts to change their opinions.[1] In the late 1960s, researchers found that real effectiveness of respirators in the workplaces were significantly lower than during tests in laboratories.

Therefore, since the 1970s, specialists started RPD tests in workplaces (in industrialized countries). The results of these studies showed that the real effectiveness of respirators were much lower, than in the laboratories (in general). Specialists have begun to use the results of workplace testing for developing regulations (governing the selection RPD[2] and organization of their usage) for limits of the safe allowable use of all RPD designs.[3]

Background

The invention of the first personal sampling pump[4][5] (1958) made it possible to simultaneously measure the concentrations of air pollutions outside the respirator mask, and at the same time - pollution of inhaled air (under a facepiece). Comparison of these measurement results show the effectiveness of respiratory protective equipment. But until the 1970s experts mistakenly believed that the protective properties of the respirator under laboratory and in the production conditions are not significantly different. Measuring the effectiveness of respirators under production conditions were not performed; and limits of areas of safe use for different types of respirators were established on the basis of laboratory tests only.

But the results of the first workplace studies have shown that the effectiveness of respirators all designs - is very fickle, and strongly depend on the correctness of their use (continuous use in polluted atmosphere, etc...), and on the leakage of contaminated air under the mask through the gaps between it and the worker's face. It was found that respirators' efficiency in the workplaces were much lower, as compared to laboratory conditions. This has led to revise the boundaries of the application of RPE different designs, and prompted to develop requirements for the organization of their application, fixing them in the national legislation.[6][7] The results of measurements forced to pay more attention to the technical methods of protection (sealing, ventilation, automation, changing technology, and others.).

If the facepiece of the respirator is tight-fitting one (elastomeric quarter or half masks, filtering facepieces, or full-face masks), efficiency decreases due to leakage of unfiltered air through the gaps between the mask and face. These gaps are formed due to the fact that while the employees do a variety of movements that do not do the testers in the lab, and due to the fact that even properly dressed mask "slipping" sometimes.

If respirator facepiece is loosely fitting one (hoods, helmets etc.) polluted air can also enter the breathing zone due to its injection (with moving stream of ambient air, unless it is motionless). But there are no significant drafts in the laboratory during RPD approval tests.

A small number of testers can not simulate all the variety of faces of millions of workers (their shapes and sizes), and about 20 minutes at a certification lab test[8] can not simulate all the variety of movements performed in the millions different workplaces. In addition, testers put on and wear masks more slow and accurate than the workers.

Published research on the effectiveness of respirators, carried out in the workplaces

The initial stage (1970s - 1980s)

(1974)[9] The researchers studied the effectiveness of respirators used by miners. Scientists simultaneously measured dust concentrations with the personal samplers and two dust collectors - without mask and in the facepiece. Also, they measured the proportion of time, then the respirators were used by miners. For this purpose, two thermistor (one in the facepiece, the other on the belt) were used; over-heating PTC with expired air was a sign of wearing a mask. Because convenience of the respirators affect on the timeliness of its usage, scientists have studied the opinion of the miners on the use of respirators. A detailed report was published before the publication of the article.[10]

(1974)[11] The study found that respirators can be a good addition to the effective dedusting ventilation. The authors recommended to carry out medical examination of workers - in employment and periodically.

(1975)[12] Experts measured the concentration of dust under respiratory protective devices of workers-sandblasters, and outside - but not simultaneously. The measurement results showed that exposure to air pollution on employees exceeds the permissible value, and that the supply of clean air into the hood reduces adverse effects. Also, measurements have shown that there may be excessive exposure to workers during breaks (when the respirator may be withdrawn); and discovered the fault of some respirators. Authors recommended: to organize the correct application of RPD, to reduce the concentration of dust in the air, and apply the abrasive material with a lower silica content.

(1976)[13] The concentrations of sulfur dioxide were measured under the negative pressure filtering respirator with elastomeric half mask, and in the breathing zone (simultaneously); and the results were used to calculate the respirator protection factors PF (such as the concentration ratio, ambient to in-facepiece). Experts analyzed the results of only those measurements, during which the masks were not removed. They found a positive relationship between a comfortableness of respirators, and their effectiveness, as the workers tightened the straps of harness at the convenient masks much stronger.

(1979)[14] Efficiency of self contained breathing apparatus (SCBA) MSA has been studied when they were used by firefighters. This SCBA had had air supply into the mask with "on demand" mode (with negative pressure under the mask during inhalation). Evaluation of the effectiveness of the respirator was conducted by determining the content of carboxyhemoglobin in the blood immediately after the cessation of fire extinguishing. Carboxyhemoglobin formed due to inhalation of carbon monoxide. The biomonitoring results shown: (1) the intermittently usage of these respirators makes it totally ineffective; (2) even in continuous usage of such breathing apparatus does not provide effective protection. The results of this study (and other similar studies) led to restrict the use of respirators with fresh air supply "on demand"; and to prohibit their use in fighting fires. US and EU legislation obliges to use only self-contained breathing apparatus with "pressure-demand" mode of air supply (it provide positive pressure under the mask during inhalation) in extinguishing fires.

(1980)[15] Evaluating the effectiveness of RPE was performed with biomonitoring. Researchers measured a styrene concentration in the expired air and in the urine. Since the absorption of styrene through skin was small, respirators were able to provide reliable protection of workers.

(1980)[16] This study clearly showed that using respirators result (exposure to harmful substances on workers) is highly dependent on the organization of their application, and on training of the workers: Employees use a respirator several times. The average protection factor of the respirator in one of the workers (who always used a respirator in a timely and accurately), proved to be 26 times greater than that of all other workers. The authors have raised the question of the need to describe the effectiveness of the respirator using different terms. One term - for cases of timely application of the respirator, and the other - for use with interruptions (for description the real protection of employees).

(1983)[17] Employees used a respirator with forced air supply to the facepiece; expected protection factor = 1000 (and more). But measured protection factors were considerably lower: 4.5 - 62 times. This disparity has prompted experts to conduct additional research to discover the causes of differenses.[18]

(1983)[18] Employees used a respirator (PAPR): air flow 184 l/min, the degree of air purification with filters 99.97%. But they are often discovered climbing of its face shield, and the minimum protection factors reaches 1.1, 1.2 ... . Some of respirators do not provide a snug fit to the face of the faces. Measurement results showed that the rest in the room with a clean air greatly reduces the impact of air pollution on the workers, and that respirators alone can not reliably protect them. It was also found that the calculation of the protection factors may give different results for different chemicals (for the same measurement carried out).

(1984)[19] Measured respirators' protection factors were very unstable. Scientists have proposed to establish the boundaries of the safe use of respirators based on the results obtained not in the laboratories, but in the workplaces, under application without interruption. This principle, with some variations, is used in developed countries today. Experts proposed to establish the expected protection factors so that the real effectiveness was greater than the expected effectiveness with a probability of 90% and in 95% of cases. The authors analyzed the results, and offered to reduce the permissible usage limits of the half-mask respirators with forced air supply (PAPR) from 500 to 50 PEL.

(1984)[20] Experts have studied the effectiveness of half mask respirators, used by employees with and without a beard under the exposure of coarse dust. The hair on the faces of the staff did not lead to a decrease in the effectiveness of respirators. This result can be explained by the fact that the dust was large, and it passes through the gap only partially. All Western manuals require workers shave face when using respirators with tight-fitting facepieces.

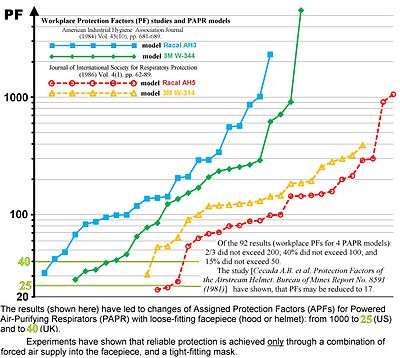

(1984)[21] This study was the third study ([18][19]), which showed low efficiency respirators (Powered air-purifying respirator with loose-fitting facepiece, hood or helmet), which consistently provides reliable protection in the laboratory (PF>1000). The minimum protection factor of respirators, applied continuously, were as follows: for the 3M model - 28, and for the Racal model - 42.

A significant difference between the real and laboratory efficiency prompted the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) released in 1982 two informational messages on respirators, warning consumers about the low effectiveness of RPD of the type that is expected to provide reliable protection.[23] The experts were alarmed: they do not understand why (after the supplying more than 115 liters of clean air per minute under the facepiece) there are a lot of pollution in the inhaled air.

- The results of these investigations led to a decrease of the expected (assigned) protection factor (APF) of such respirators 40-fold, from 1000 to 25 (US). The authors said that the study of one of the tested respirator models in the wind tunnel has been found reduction of the protection factor up to 17 at an air speed of 2 m/s airflow in certain directions.[24]

This study showed that laboratory tests can not be used as a reliable indicator of the effectiveness of respiratory protective equipment. Authors are encouraged to use the results of measurements of respirators' protection factors in the workplaces (with continuous use) to develop reasonable restrictions for different types of respiratory protective equipment.

- Research efficiency in the workplace led to develop a special terminology to adequately describe the effectiveness of respirators.

Public discussion of the proposed terms were carried out in 1982-1986.[25][26][27][28] As a result of this discussion, the experts gave definitions for the six respirator protection factors that can be measured in different conditions in the workplaces and in the laboratories. These definitions began to be used officially,[2] as well as in the preparation of articles about the trials of respirators.[29]

For example, the assigned protection factor (APF), is the minimum PF, which RPD (of this type) must ensure if: the respirator will be used by trained and taught workers, after individual selection masks to face an employee; if it is to be used without interruption in the polluted atmosphere - in most cases (but not in all cases). The experts recommended to develop APF values based on measurements of the protection factors in the workplace, or in considering the values of APF of similar respirators' types.

- They found that if the protection factors are not stable, the average efficiency is strongly dependent on smaller values:[30] If the same worker used respirator twice, and if the protection factor was 230,000 in the first case, and the protection factor was 19 in the second (example values from[31]), the average protection factor was only 38. (Penetrations in the first and second cases are 5.26% and 0%, respectively; and the average penetration is equal to 2.63%). Medium PF is strongly dependent on the minimum values.

Other workers[31]) also meet very strong volatility of efficiency (for example, the protection factor of 51 000 and 13 for the same worker).

The initial stage of research yielded the following results: experts developed a common terminology to describe the protective properties of the respirators; a methodology for measuring protection factors in different conditions of respirators' usage in the workplaces and laboratories; and the realization that national legislation should set limits for the use of all types of respirators based on their performance, measured not in the laboratory, but in the workplaces. The first studies also clearly confirmed that the use of respirators is the most unreliable method of protecting workers from all known methods. Therefore, respirators should be used only when other methods can not be used; or when other methods can not reduce the exposure of air pollution on people to an acceptable safe level.

Since the effectiveness of respirators may vary depending on different circumstances related to the organization of their application, the RPE should be used as part of a respiratory protection program (a complex of measures aimed at eliminating the causes which may reduce the effectiveness of respiratory protection).

Further studies

(1984)[32] Workers used disposable half-mask respirators, that protected them from the mercury vapor in the enterprise, produces chlorine. Range of measured protection factors - from 9 to 63. Perhaps the real effectiveness of respirators differ from measured - but take into account the deposition of harmful substances in the respiratory tract was too difficult.

(1984)[33] The study describes the measurement of the effectiveness of half-mask respirators, which has been used to protect against lead aerosols.

(1985)[34] Report of the exhibition and conference.[35] The researchers presented their measurements of efficiency of respirators that have been used to protect against asbestos during removal of insulation and fire-retardant ceiling.

(1986)[36] The researchers studied the effectiveness of respirators and at the same time - the efficiency of the workers protection (by biomonitoring). They found a correlation between the respirator protection factors and lead concentrations in the blood. The authors noted that the violation of personal hygiene can lead to the entry into the body large amounts of lead (despite the use of effective respirators in the workplace).

(1986)[37] Respirators used for the protection of organic solvent vapors. In order to assess their effectiveness, the researchers used passive diffusion monitors. Exposure of pollution on the workers was excessive due to the fact that the masks used in the polluted atmosphere intermittently.

(1986)[22] Researchers have studied helmets with forced air supply (PAPR). These respirators protect workers from lead aerosol during battery production.

(1986)[38] Report of the exhibition and conference.[35] The researchers reported the results of measurements of the protective properties of the hood with forced air supply. The respirators were used to protect workers against asbestos during brake manufacturing.

(1987)[39] The researchers studied the effectiveness of the filtering facepieces. They made a mistake: they measured the in-facepiece concentration by weighing, but the dust contains cement. Dust humidification increased its mass, and drying the in-facepiece filters can not remove moisture. The error was detected; and the planning of new studies in the majority of cases employ the chemical analysis of collected dust. The specialists began to point to what chemical element the measured protection factors were defined.

(1987)[40] The author has studied the effectiveness of the protection of workers who removed the old paint. Employees used a negative pressure filtering respirators with a full face mask; concentration of solvents under the mask was measured using a diffusion monitors. The author said that the high humidity of expired air were not interfere with the measurements.

(1987)[41] Report of the exhibition and conference.[35] The report describes the measurement of the effectiveness of respirators that workers used to protect against aerosols of aluminum, titanium and silica during the polishing and grinding.

(1987)[42] Report of the exhibition and conference.[35] The report described the measurement of protection factors airline respirator. The workers used RPD to protect against silica at shipyard.

(1989)[43] The workers used a helmet with forced air supply. This helmet was joined to a waterproof suit with the help of a zip fastener. This made it possible to obtain high protection factors (~ 350), and protect workers securely. The results of researches of the show, in order to ensure reliable protection of people with the help of a respirator, the employer shall pay attention to the organization and use of RPD, and to the planning of the work.

(1989)[44] Report of the exhibition and conference.[35] The researchers studied the protective properties of negative pressure respirator with full face masks. These RPE used to protect employees from the lead in the enterprise, which was made this metal.

(1989)[45] Report of the exhibition and conference.[35] The researchers studied the protective properties of SARs, which were used for protection against iron and quartz aerosols during abrasive machining of castings.

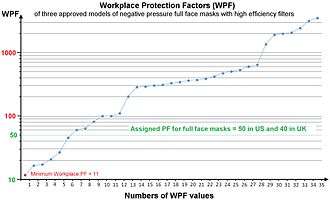

(1990)[46] Researchers measured protection factors of three models certified negative pressure filtering respirators with full face masks. Surprisingly, the values obtained were much lower than expected; and they are significantly smaller than the values previously obtained in the laboratories. Minimum PF values were: 11; 16; 17; 20; 26 ... (expected PF >900). For one of three models, there are no any measurements, when its protection factor exceeded 500 - et all.

- Assigned Protection Factors for the respirators of this type have been reduced from 900 to 40 due to this study (in the UK). US restrictions are similar to English: Assigned PF = 50.[7]

(1990)[47] Measurement results showed that the effectiveness of the protection of employees of various specialties (using the same half mask respirators) may be different; and that the effectiveness of one and the same worker may differ by tens of times.

(1990)[48] Report of the exhibition and conference.[35] The authors reported respirator protection factor measurements, that were applied for protection from aluminum dust in the production of this metal.

(1990)[49] Report of the exhibition and conference.[35] Experts have reported PF of filtering facepiece respirators, used to protect against lead and zinc in brass casting.

(1990)[50] Report of the exhibition and conference.[35] The researchers studied the protective properties of full face masks with forced air supply (PAPR). These RPE used to protect employees from the lead in the enterprise, which was made this metal.

(1990)[51] Report of the exhibition and conference.[35] The researchers studied the protective properties of the helmet with forced air supply (Powered air-purifying respirator). These RPE used to protect employees from the steroids in the pharmaceutical industry.

(1991)[52] Measurement of protective properties of half mask respirators showed that they are ineffective, and that their protective properties are significantly higher in the laboratory than in the workplace.

(1992)[53] The authors made a review of the researches of RPE efficiency in the workplaces. This article shows a significant difference between the real and lab efficiencies, that forced to carry out researches of respirators in the workplaces, and develop adequate terminology. The article also describes the problems when evaluating the protective properties of the high efficiency RPE types: very low pollution of air under the facepiece preventing the accurate analysis; and it is difficult to find a workplace with a sufficiently high concentration of air pollution.

(1992)[54] Report of the exhibition and conference.[35] Scientists studied respirators (filtering facepieces), used to protect against fume of iron, manganese, titanium and zinc during welding and abrasion on the shipyard.

(1993)[55] The respirators used by workers continuously. The effectiveness of half-mask with forced air supply (PAPR) is higher than one of negative pressure half-mask.

(1993)[56] The researchers studied the effectiveness of respirators to protect workers from styrene. The authors used two methods. They measured the concentrations of styrene under the mask and the outside it (for calculating the protection factor); and they conducted biomonitoring (determined concentration of phenylglyoxylic acid and mandelic acid in the urine). These substances are formed during the decomposition of styrene in humans. The average value of a respirator protection factors (calculated with the measured concentrations) was equal to 4; and the average intake of harmful substance in the body of the worker (measured using biomonitoring) decreased by 3 times. The authors recommended determine the impact of styrene on the workers by biomonitooring.

(1993)[57] Evaluating the effectiveness of a respirator was done using biomonitoring. The authors measured the concentrations of lead and zinc protoporphyrin in blood. The lead absorption by the human body increases these concentrations. The respirators usage reduced the lead ingress into the body of the employees. The researchers recommended to show the measurement results to employees to encourage the timely use of respirators, and personal hygiene.

(1993)[58] The authors studied the filtering facepieces respirators. The researchers found a positive correlation between respirators' protection factors (when RPE used without interruption) and the concentration of pollutants in the ambient air.

(1993)[59] Report of the exhibition and conference.[35] The staff dismantled the old oven. They used a hose respirators (Supplied Air Respirator, SAR) for protection against quartz aerosol.

(1993-1994)[60] Experts have studied the protective properties of the different elastomeric respirators and filtering facepieces. The workers used these respirators in several companies producing paint, flame retardants and batteries.

(1994)[61] Report of the exhibition and conference.[35] Experts measured protection coefficients of half mask respirators during cutting of old ships. The workers were exposed to the lead aerosol.

(1995)[62] The author carried out a statistical analysis of the results of all studies of half mask respirator (when they are used without interruption). He concluded that in most cases (it is - all the cases together) protection factors were greater than 10. But the expert did not realize just how fickle the protection coefficients for individual employees, and that the continuous use is not always possible.

(1995)[63] Research has shown that different types of respirators (quarter masks, half masks and PAPR with loose-fitting hood) provide a similar (low) degree of protection when its were used intermittently. The researchers interviewed the workers to determine deficiencies of RPE different designs, and gave advice on the selection of respirators for different types of work.

(1996)[64] Ventilation and use of respirators (without interruption) enables reliably protect workers.

(1996)[65] Studies have shown that the use of respirators (with technical means of collective protection) provides the desired reduction in the harmful effects on workers.

(1996)[66] The workers use the hoods with a continuous flow of a clean air under its. They purified the bridge from old paint. Exposure of lead on the employees exceeds the maximum permissible exposure.

(1996)[67] This article describes the reasons how ANSI has limited the use of respirators of different designs (Assigned PF). To develop values of APF ANSI used: (1) results of the measurements of RPD efficiency in the workplaces; (2) APF of respirators with similar design. Only in the absence of this information, the experts used the measurements of efficiency in the laboratory (than them imitate the real work).

- Designed restrictions (US[7]) are valid only when the respirators are used in the polluted atmosphere without interruptions, but this is not always possible.

(1998)[68] The workers use respirators with full face masks, air is supplied under a mask forcibly - from the block of filtration and purification. Components of respirators differ from the factory set (workers used the most appropriate mask, comfortable units clean and cheap filters - from different manufacturers). Of the 21 cases, the workers received adequate protection only in eight cases. The minimum protection factor (5) was significantly less than expected from the respirator of this design (1000). The authors recommended the use of working methods that create less dust concentration; train workers; and prohibit the use of RPE with non-approval configuration.

(1998)[69] The authors studied the respirator protection factors of the same type (half-mask), using different models. The effectiveness of different respirator models can differ significantly.

(1999)[70] Respirators used to protect workers against styrene. Scientists also examined the absorption of styrene through a skin during the study. Biological monitoring has shown that absorption through the skin is small; and respirators affect on the styrene exposure dose greater than the use of protective clothing.

(1999)[71] The researchers used an original method for measuring full facepiece performance. Determining the concentration of harmful substances under the mask can be very difficult, since the concentration can be very small. To solve this problem, the researchers attached to the mask hood under which supplied test gas (sulfur hexafluoride). Since workers do not travel long distances, the gas concentration was measured by stationary devices with long tubes. This method allows to accurately measure the gas leakage through the gaps between the mask and the face. They also used the standard EU methodology for determining leakage, which is used for respirator certification.

(2000)[72] The authors studied the effectiveness of respirators (they measured the styrene concentrations outside the mask, and under the mask); and the real effectiveness of the protection of workers (styrene concentration in the urine). It turned out that the effectiveness of the protection of workers (with impermanent usage of respirators) is significantly lower than the effectiveness of respirators themselves: the people's exposure decreased by only 5-60%, and exceeded the limit.

(2000)[73] The authors studied the filtering half-mask respirators. The workers used different models: part of respirators had forced supply of air from the cleaning unit, and a part was the usual negative pressure half masks. The results showed that if the workers use respirators intermittently, their efficiency are low, and significantly lower than expected: In the first type respirators 85-91% values of protection factors were lower than expected Assigned PF = 50; and the second type of RPE provide protection factor in 82-89% of cases lower than the expected APF = 10.

(2000)[74] Respirators field study has shown that the effectiveness of the protection of the shipyard workers from the styrene exposure may also depend on the concentration of pollutant in the dining room air. The use of respirators in the workplace without interruption reliably protect workers.

(2000)[75] Protection factors of filtering facepieces were measured. Workers used respirators intermittently. Because working conditions were improved (through the use of vacuum cleaners instead of dry sweeping the floor, ets), the intermittently usage of the respirators allowed protect workers to the extent necessary.

(2001)[76] The application the Powered Air Purifying Respirator (PAPR) allows reliably protect workers during grinding. Measured PF were >1000.

(2001)[77] Report of the exhibition and conference.[35] The authors described the measurement of respirators' performance (PAPR with hood) in the enterprise, is made of nickel-cadmium batteries. The air was polluted by cadmium.

(2002)[78] Protection factors of half mask respirators that are not always used (because of high air temperature) have been very low. Half of the PF values were less than 2. The authors recommended to make general ventilation; and use PAPR (air blowing face may make use of such respirators more acceptable at a high temperature).

(2002)[79] The authors analyzed the expected values of protection factors and take into account the appearance of a mask during inspiration (at different flow of inhaled air). They found that efficiency of a Supplied Air Respirators (SAR) with a constant air feed mode can be lower than expected, and recommended to reduce Assigned PF from 100 to 40.

- The proposed reduction was carried out in Great Britain.[80]

(2002)[81] Measuring the effectiveness of respirators, individually chosen for the workers, showed that they securely protect workers from welding fumes. The respirators were used without interruption.

(2003)[31] Experts studying how mask fit to the faces of the workers affect on the protection factors of the respirators. Protection Factor - a random variable, which depends on many factors and it is not predictable; however respirator masks that conform to the workers' faces, provide better protection on average. Similar results were also obtained in the laboratories. These results became the basis of the legal requirements: the employer is obliged to pick up the mask to the face of each employee individually, and to check compliance (with the form and size) with the instruments. One of the measurements showed that ordinary low-cost half mask can provide very high protection factor (230,000) sometimes. However, this protection is unreliable: the next measurement in the same working (which used the same mask) showed that the protection factor of only 19. The average value of the protection ratio for these two measurements was ~ 38. Other workers also meet any strong volatility of efficiency (for example, the protection factor of 51 000 and 13 for the same worker).

(2004)[82] The textbook[2] states that the expected degreee of protection is a such quantity, that the respirator will provide for a certain proportion of the workers, and with a certain probability. However, experts did not have enough results of PF measurements for the same worker repeatedly. Consequently, the expected effectiveness started (in practice) equal to the lower 95% confidence limit of the set values of measurement results. Later, in several studies, PF measurements were repeated to for the same worker, and specialists conducted statistical analysis. Nikas and Neyghauz[82] tried to determine - then the expected PF will reliably protect not less than 95% of workers in more than 95% of cases of RPE usage. They took into account the volatility of PF of the individual worker and volatility of the average (mean) PF for the different workers. It turned out that then the expected PF (Assigned PF) = 10 efficiency respirators will be insufficient, and they are advised to reduce the Assigned PF to 5 for negative pressure half mask.

(2004)[83] After individual selection masks, checking their fit to the faces, and when they are used in a timely manner - the measured effectiveness of the workers protection has not been lower than expected.

(2005)[84] This article describes a unique portable device. The instrument determines the count concentration of aerosol particles outside the mask, and under the mask (during operation in real time). This instrument determines the concentration for 5 optical particle diameters ranges separately. The measurement results demonstrated that the effectiveness of the filtering facepiece (under a constant application) were very unstable; and that smaller particles leak under a mask better, than larger ones.

(2005)[85] Experts measured the protective properties of respirators that are used to protect against inhalation of fungal spores and bacteria. The result showed that the efficiency depends on the type of microorganism.

(2007)[86] Experts studied the protective properties of full face masks. The measurements showed that the workers were adequately protected. The duration of the measurements was 1–3 hours. In these circumstances, of the 52 measurements, in 2 cases, the workers had removed the mask (because they had something to say to each other) - and these results were not taken into account in the analysis. However, use of respirators intermittently drastically reduces their efficiency. This shows how important to correctly organize the use of respirators, and to provide workers with the intercom stations (if necessary).

(2007)[87] Respirators' protection factor was measured under the conditions of exposure of workers with xylene and ethylbenzene vapors. Also, the team members conducted biomonitoring of exposure. They measured the concentration methylhippuric acid in the urine. Scientists have found a correlation between the concentrations of xylene in air and the concentrations of methylhippuric acid in the urine; and calculated the proportion of solvent entering the body through the lungs and through the skin. It turned out that if the respirator protection factors was more than 17-25, more than half of xylene enters to the painters' body through unprotected skin. The authors recommended the use of more hygienic methods of painting, since the use of skin protection continuously in hot tropical conditions difficult to achieve.

(2007)[88] The authors of this study repeated mathematical modeling of the effectiveness of respirators, which had previously performed by Nikas and Neyghauz.[82] The authors have complicated mathematical model, and take into account the results of new researches. Since the protection factors in the new studies were large, the author got the high anticipated effectiveness of half masks respirators - no less than 10 times.

(2007)[89] Respirators has been used continuously. The filtering half masks provide the required protection for steel plant employees.

(2007)[90] The workers used a high-quality half mask respirators; and they were trained. Mask was selected to employees individually and their compliance with the face were checked. Employees perform sedentary work, the air was contaminated with coarse dust. So, the lowest protection factor (PF=24) was much greater than expected (Assigned PF = 10). However, these conditions may not be available at other workplaces; and therefore the authors recommended do not change the Assigned PF for half mask respirator.

(2008)[91] PAPR protect workers securely. In all cases, the concentration of harmful substances (under a mask) was less than the threshold sensitivity of the analysis method used. The authors noted that the tests of high efficiency respirators require workplaces with high polluted air, and these places are hard to find.

(2009)[92] Workers used high quality masks - on time and correctly. So, in most cases pollution of inhaled air (under a mask) is below the threshold sensitivity of the analysis method used.

(2010)[93] Engineers used a special instrument for the study of respirators.[84] Results showed that the protection efficiency of particles with a large optical diameter higher than that for particles with smaller optical diameter.

(2012)[94][95] The authors review work described research on the effectiveness of helmets with forced filtered air flow to the organs of respiration (model Airstreem), used in metallurgical enterprises in England.

(2015)[96] Experts studied the PAPR performance. Respirators provide reliable protection of workers from the nanoparticles.

| Estimated performance parameter | Number of studies† | The number of research participants | Number of the measurements |

|---|---|---|---|

| Effective Protection Factors | 18 | >381 | >526 |

| Workplace Protection Factors | 46 | >569 | >1853 |

| Biomonitoring | 9 | >193 | >644 |

| Total: | 75 | >1141 | >3061 |

† - Only the published studies. Many studies have been conducted, but they were not published. However, their results were known and used.

- These studies gave information about the real effectiveness of respiratory protective equipment; of their unreliability, and studies have shown some circumstances affect and may affect the effectiveness of the protection. Biomonitoring revealed the final result of the use of respirators - real, actual reduction of harmful substances entering the body. The studies have become the basis for the development of national legislation in the developed countries, which governs the selection and organization of the use of respirators by the employer. Specifically, as the lowest values of protection factors of constant wear half mask reaching 1.6 (and reaches 1, when unstable worn), it shall not be used when the air pollution exceeds 10 PEL in the US. And as the lowest values of protection factors of constant wear full face mask reaching 11,[46] it shall not be used when the air pollution exceeds 40 OEL in the UK.

- The results of measurements RPE efficiency not only in the laboratory but also in real production conditions, allowed to develop evidence-based guidelines for the selection and organization of the use of respirators.[6][7][97]

Studies of the effectiveness of respiratory protective equipment in coal mining

The authors have shown that the average decrease dustiness of inhaled air in coal mining in the UK due to the use of respirators is 41% (1.7 times).[98] Low efficiency respirators due to the fact that the miners used respirators intermittently or not used at all (in the conditions of effective ventilation and low dust concentration). They can not determine when the dust concentration is more than acceptable, and when it is necessary to use a respirator.

The handbook[99] discusses the results of measurements of respirators' performance. The dust concentration was reduced by 92% with the use of half mask respirators while working longwall shearer; and decreased three times (in average). Helmet with forced filtering air supply (PAPR) reduces the concentration of dust in half. The expected decrease in dust concentration of the two types of respirators are 10 and 25 respectively. In subsequent publications of CDC (on the subject of reducing the dust content in underground mining) RPE are not mentioned at all.

The use of filtering facepieces model "Lepestok" during the Chernobyl accident

Liquidation of consequences of the Chernobyl accident required the reliable protection of people from radioactive aerosols. Even a small amount of radioactive substances can seriously harm human health if it enters into their bodies[100] (because of the small distance from the tissues). Aerosol particles deposited in the lungs, can remain there for many years, and it increases the risk of diseases. Eliminating the consequences of the accident were carried out the best experts, including members of the Kurchatov Institute. Only one of the manufacturers RPD sent to Chernobyl approximately 300,000 negative pressure filtering facepieces model "Lepestok" only in June 1986.[101] These respirators are considered to be very effective (the declared protection factor of 200 for most common model "Lepestok-200").

But the application of this model on a large scale has revealed numerous cases of excessive exposure to air pollution on people. This has led experts to question the high efficiency of the respirator, and it is similar to the events in the US nuclear industry in the late 1960s.[1] Doubts were strong; and they are forced to carry out an independent study of the effectiveness in a foreign laboratory.[102] Specialists conducted parallel attempts to identify the reasons for the low efficiency of the respirator in Chernobyl.[103]

The results of research in Chernobyl and in the United States were similar: the filter material is well caught a fine aerosol,[104] and created a small resistance to the passage of air through it; but a lot of unfiltered air passes through the gap between the mask and face. Research has shown that one can expect the minimum values of the protection factor 2÷8,[105] or even 1.5.[102]

Representatives of the institution in which the model of respirator was developed, given their very original interpretation of the results of independent (foreign) tests:

... in 20% of cases the protection factor (fit factor) exceeded the declared value (200). ... Consequently, the respirator model provides the declared efficiency.

.

In addition, the respirator designers stated that experts from Kurchatov Institute conducted their measurements "illiterate".[103]

Many cases of excessive exposure to air pollution during operation at the Chernobyl plant did not lead to a change in assessments of the effectiveness of respirators - as happened in the United States before.

Analysis of the results of measurements of the respirators' performance at workplaces

Field measurement results showed that the respirators are the most recent and the most unreliable means of protection. The effectiveness of respiratory protective equipment is unstable and unpredictable. Respirators cannot substitute other measures, that reduce the impact of air pollution on the staff (sealing equipment, ventilation and so on), but only supplement them. Respirators are not convenient, they create discomfort and irritation, and prevent communication.[86] The reduction of the field of view leads to an increase in the risk of accidents.

RPE reinforce overheating at a high air temperature.[78] These and other deficiencies often prevent use of respirators in the polluted atmosphere without interruptions. But if the RPD is not used, it becomes useless.

Workers using respirators partially lose performance. Industrial hygienists know many cases where harmful substances enter the body not through the respiratory system, but in other ways (through skin[87]). Even the timely use of a respirator may not be sufficient for reliable protection of workers.[56]

If the respiratory system is the main way of receipt of harmful substances in the body, and if the use of other means of protection does not allow to reduce the impact to an acceptable value, employee must use respirators. They should be selected taking into account their effectiveness (it depends on the respirator type); masks should be chosen for employees personally; and workers should be learned, and trained - in accordance with legal requirements. This reduces the risk of occupational diseases as much as possible.

Using the results of measurements in the workplaces

Comparison of the results of tests of various types of respirators in the laboratories and in the workplaces showed that laboratory tests do not allow to properly assess the real effectiveness of respirators (even if they are applied without interruption). Therefore, legislation in industrialized countries establishes limitations on the use of all types of respirators, taking into account such differences, and taking into account the results of field trials. This field measurements revealed low efficiency of several types of respirators, and forced more strictly limit their use: for negative pressure air-purifying respirators with full face mask and high efficiency filters - from 500 PEL to 50 PEL (USA[19]), from 900 OEL to 40 OEL (UK[78]); for Powered Air-Purifying Respirators with loose-fitting facepiece (hood or helmet) — from 1000 PEL to 25 PEL (USA[21]), PAPR with half mask — from 500 PEL to 50 PEL (USA[19]), for supplied Air Respirators with full face mask and continuous air supply mode - from 100 OEL to 40 OEL (UK[79]); for SCBA and SAR with air supply on demand mode — from 100 PEL to 50 PEL (USA).

The results of numerous field tests and analysis, led to the restriction of application limits of filtering facepieces and negative pressure half mask respirators to 10 PEL in US.[106]

| RPD type, country | Requirements for the protection factor for certification (2013) | Limitations prior the workplace testing (year) | Limitations after the workplace testing (2013) | The minimum values of the measured workplace protection factors |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PAPR with helmet, USA | > 250 000[8] | up to 1000 PEL | up to 25 PEL[7] | 28, 42 ... |

| Negative pressure air-purifying respirator with full face mask, USA | > 250 000[8] | up to 100 PEL (1980) | up to 50 PEL[7] | 11, 16, 17 ... |

| Negative pressure air-purifying respirator with full face mask, UK | > 2000 (for gases) or >1000 (for aerosols) | up to 900 OEL (1980) | up to 40 OEL | |

| Negative pressure air-purifying respirator with half mask facepiece, USA | > 25 000[8] | up to 10 PEL (since the 1960s[7]) | 2.2, 2.8, 4 ... | |

| Self-contained breathing apparatus with air supply on demand, USA | > 250 000[8] | up to 1000 PEL (1992) | up to 50 PEL[7] | (monitoring showed a low efficiency under the carbon monoxide exposure) |

The significant difference between the real and laboratory efficiency prompted the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health to require the manufacturers of high-performance RPE perform its testing at the adequate workplaces (as a requirement for respirator certification in the United States[53]).

Due to the fact that respirators wearing cannot provide a reliable protection, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health has developed a guide to reduce the dust concentration: in the underground coal mines;[107] in the other mines;[108] and other similar documents with specific recommendations.

See also

References

- 1 2 Cralley, Lesly; Cralley, Lester (1985). "..". Patty's Industrial Hygiene and Toxicology. 3A (2 ed.). New York: Willey-Interscience. pp. 677–678. ISBN 0 471-86137-5.

- 1 2 3 Miller, Donald; et al. (1987). NIOSH Respirator Decision Logic. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 87-108. National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. p. 61. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ Kirillov, Vladimir; et al. (2014). "Overview of Industrial Testing Outcome of Respiratory Organs Personal Protection Equipment". Toxicological Review (in English & in Russian). Moscow: Federal Budgetary Health Institution (FBHI) "Russian Register of Potentially Hazardous Chemical and Biological Substances" of the Rospotrebnadzor (6(129)): 44–49. doi:10.17686/sced_rusnauka_2014-1034. ISSN 0869-7922.

- ↑ Sherwood, Robert (1966). "On the Interpretation of Air Sampling for Radioactive Particles". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 27 (2): 98–109. doi:10.1080/00028896609342800. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Sherwood, Robert; Greenhalgh, D.M.S. (1960). "A Personal Air Sampler". The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. Oxford, UK: The British Occupational Hygiene Society - Oxford University Press. 2 (2): 127–132. doi:10.1093/annhyg/2.2.127. ISSN 0003-4878. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- 1 2 Technical Committee PH/4, Respiratory protection, ed. (1997). British Standard BS 4275:1997 "Guide to implementing an effective respiratory protective device programme" (3 ed.). 389 Chiswick High Road, London: British Standards Institution. ISBN 0-580-28915 X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 OSHA standard 29 CFR 1910.134 "Respiratory Protection"

- 1 2 3 4 5 NIOSH standard 42 Code of Federal Register Part 84 "Respiratory Protective Devices"

- ↑ Harris, H.E.; DeSieghardt, W.C.; Burgess, W. A.; Reist, Parker (1974). "Respirator Usage and Effectiveness in Bituminous Coal Mining Operations". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 35 (3): 159–164. doi:10.1080/0002889748507018. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Harris, H.E.; DeSieghard, W.C. (1973). Respiratory Protection and Respirable Dust in Underground Coal Mines (PDF). Everett, Massachusetts: ACS Division of Energy & Fuel - Preprints. pp. 165–179.

- ↑ Revoir, William (1974). "Respirators for Protection against Cotton Dust". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 35 (8): 503–510. doi:10.1080/0002889748507065. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Behzad, Samimi; Neilson, Arthur; Weill, Hans; Ziskind, Morton (1975). "The Efficiency of Protective Hoods Used by Sandblasters to Reduce Silica Dust Exposure". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 36 (2): 140–148. doi:10.1080/0002889758507222. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Moore, David; Smith, Thomas (1976). "Measurement of protection factors of chemical cartridge, half-mask respirators under working conditions in a copper smelter". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 37 (8): 453–458. doi:10.1080/0002889768507495. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Levin, Marshal (1979). "Respirator use and protection from exposure to carbon monoxide". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 40 (9): 832–834. doi:10.1080/15298667991430361. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Brooks, Stuart; Anderson, Loren; Emmett, Edward; Carson, Arch; Tsay, Jia-Yeong; Elia, Victor; Buncher, Ralph; Karbowsky, Robert (1980). "The Effects of Protective Equipment on Styrene Exposure in Workers in the Reinforced Plastics Industry". Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis. 35 (5): 287–294. doi:10.1080/00039896.1980.10667507. ISSN 0003-9896. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Smith, Thomas; Ferrel, Willard; Varner, Michael; Putnam, Robert (1980). "Inhalation exposure of cadmium workers: effects of respirator usage". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 41 (9): 624–629. doi:10.1080/15298668091425400. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Myers, Warren; Peach, M.J. III (1983). "Performance measurements on a powered air-purifying respirator made during actual field use in a silica bagging operation". The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. Oxford, UK: The British Occupational Hygiene Society - Oxford University Press. 27 (3): 251–259. doi:10.1093/annhyg/27.3.251. ISSN 0003-4878. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 Que Hee, Shane; Lawrence, Philip (1983). "Inhalation Exposure of Lead in Brass Foundry Workers: The Evaluation of the Effectiveness of a Powered Air-Purifying Respirator and Engineering Controls". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 44 (10): 746–751. doi:10.1080/15298668391405670. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Lenhart, Steven; Campbel, Donald (1984). "Assigned protection factors for two respirators types based upon workplace performance testing". The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. Oxford, UK: The British Occupational Hygiene Society - Oxford University Press. 28 (2): 173–182. doi:10.1093/annhyg/28.2.173. ISSN 0003-4878. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Fergin, Stanley (1984). "Respirator Evaluation for Carbon Setters with Beards". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 45 (8): 533–537. doi:10.1080/15298668491400223. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 Myers, Warren; Peach III, Michael; Cutright, Ken; Iskander, Wafik (1984). "Workplace Protection Factor Measurements on Powered Air-Purifying Respirators at a Secondary Lead Smelter: Results and Discussion". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 45 (10): 681–688. doi:10.1080/15298668491400449. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- 1 2 Myers, Warren; Peach III, Michael; Cutright, Ken; Iskander, Wafik (1986). "Field Test of Powered Air-Purifying Respirators at a Battery Manufacturing Facility". Journal of the International Society for Respiratory Protection. International Society for Respiratory Protection. 4 (1): 62–89. ISSN 0892-6298.

- ↑ Nancy J. Bollinger, Robert H. Schutz, ed. (1987). NIOSH Guide to Industrial Respiratory Protection. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No 87-116. Cincinnati, Ohio: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. p. 305.

- ↑ Cecala, Andrew B.; Volkwein, Jon C.; Thomas, Edward D.; Charles W. Urban (1981). Protection Factors of the Airstream Helmet. Bureau of Mines Report No. 8591. p. 10.

- ↑ Hack, Alan; Fairchild, Chack; Scaggs, Barbara (1982). "the forum...". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 43 (12): A14. ISSN 1542-8117.

- ↑ Dupraz, Carol (1983). "The Forum". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 44 (3): B24–B25. ISSN 1542-8117.

- ↑ Myers, Warren; Lenhart, Steven; Campbell, Donald; Provost, Glendel (1983). "The Forum". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 44 (3): B25–B26. ISSN 1542-8117.

- ↑ Guy, Harry (1985). "Respirator Performance Terminology". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 46 (5): B22,B24. ISSN 1542-8117.

- ↑ Dupraz, Carol (1986). "Letter to the Editor". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 47 (1): A12. ISSN 1542-8117.

- ↑ Sherwood, Robert (1997). "Letters to the Editor". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 58 (3): 251. doi:10.1080/00028894.1997.10399249. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 Zhuang, Ziqing; Coffey, Christopher; Campbell, Donald; Lawrence, Robert; Myers, Warren (2003). "Correlation Between Quantitative Fit Factors and Workplace Protection Factors Measured in Actual Workplace Environments at a Steel Foundry". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 64 (6): 730–738. doi:10.1080/15428110308984867. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Cohen, Howard (1984). "Determining and validating the adequacy of air-purifying respirators used in industry Part I—Evaluating the Performance of a Disposable Respirator for Protection Against Mercury Vapor". Journal of the International Society for Respiratory Protection. International Society for Respiratory Protection. 2 (3): 296–304. ISSN 0892-6298.

- ↑ Dixon, Stephen; Nelson, Thomas (1984). "Workplace Protection Factors for Negative Pressure Half-Mask Facepiece Respirators". Journal of the International Society for Respiratory Protection. International Society for Respiratory Protection. 2 (4): 347–361. ISSN 0892-6298.

- ↑ Albrecht, W.H.; Carter, G.R.; Gosselink, D.W.; Mullins, Haskell; Wilmes, D.P. (6 June 2003). "Assigned Protection Factors (29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926) - No. 5" (PDF). Federal Register. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 68 (109, Part II): 34062. ISSN 0097-6326. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 American Industrial Hygiene Conference and Exposition

- ↑ Lawrence, Grauvogel (1986). "Effectiveness of a Positive Pressure Respirator for Controlling Lead Exposure in Acid Storage Battery Manufacturing". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 47 (2): 144–146. doi:10.1080/15298668691389478. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Larsen, R.S. (1986). "A Practical Field Method for Measuring the Effectiveness of Intermittent Respirator Usage". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 47 (12): A775–A776. ISSN 1542-8117.

- ↑ Nelson, Thomas; Dixon, Stephen (6 June 2003). "Assigned Protection Factors (29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926) - No. 2" (PDF). Federal Register. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 68 (109, Part II): 34052. ISSN 0097-6326. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ↑ Reed, Laurence David; Lenhart, Steven; Stephenson, Richard; Allender, Joan (1987). "Workplace Evaluation of a Disposable Respirator in a Dusty Environment". Applied Industrial Hygiene. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 2 (2): 53–56. doi:10.1080/08828032.1987.10389249. ISSN 0882-8032. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Tchorz, K. (1987). "ORSA Tubes Worn Inside Face Masks: A Simple Means of Checking the Effectiveness of protective Filter Masks". In A. Berlin; et al. Diffusive sampling: An alternative approach to workplace air monitoring. The proc. of an Intern. symp. London: Roy. soc. of chemistry. pp. 419–422. ISBN 0-85186-343-4.

- ↑ Johnston, Alan; Mullins, Haskell (6 June 2003). "Assigned Protection Factors (29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926) - No. 16" (PDF). Federal Register. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 68 (109, Part II): 34058. ISSN 0097-6326. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ↑ Johnston, Alan; et al. (6 June 2003). "Assigned Protection Factors (29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926) - No. 28" (PDF). Federal Register. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 68 (109, Part II): 34065. ISSN 0097-6326. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ↑ Akkersdijk, H.; Bremmer, C.F.; Schliszka, C.; Spee, T. (1989). "Effect of Respiratory Protective Equipment on Exposure to Asbestos Fibres During Removal of Asbestos Insulation". The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. Oxford, UK: The British Occupational Hygiene Society - Oxford University Press. 33 (1): 113–116. doi:10.1093/annhyg/33.1.113. ISSN 0003-4878. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Colton, Craig; Johnston, Alan; Mullins, Haskell; Rhoe, C.R. (6 June 2003). "Assigned Protection Factors (29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926) - No. 2A" (PDF). Federal Register. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 68 (109, Part II): 34058. ISSN 0097-6326. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ↑ Johnston, Alan; Colton, Craig; Stokes, D.W.; Mullins, Haskell; Rhoe, C.R. (6 June 2003). "Assigned Protection Factors (29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926) - No. 20" (PDF). Federal Register. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 68 (109, Part II): 34065. ISSN 0097-6326. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 Tannahill, S.N.; Willey, R.J.; Jackson, M.H. (1990). "Workplace Protection Factors of HSE Approved Negative Pressure Full-Facepiece Dust Respirators During Asbestos Stripping: Preliminary Findings". The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. Oxford, UK: The British Occupational Hygiene Society - Oxford University Press. 34 (6): 547–552. doi:10.1093/annhyg/34.6.547. ISSN 0003-4878. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Galvin, Kit; Selvin, Selvin; Spear, Robert (1990). "Variability in protection afforded by half-mask respirators against styrene exposure in the field". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 51 (12): 625–631. doi:10.1080/15298669091370266. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Colton, Craig; Johnston, Alan; Mullins, Haskell; Rhoe, C.R.; Meyers, W.R. (6 June 2003). "Assigned Protection Factors (29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926) - No. 14" (PDF). Federal Register. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 68 (109, Part II): 34057. ISSN 0097-6326. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ↑ Colton, Craig; Mullins, Haskell; Rhoe, C.R. (6 June 2003). "Assigned Protection Factors (29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926) - No. 15" (PDF). Federal Register. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 68 (109, Part II): 34057. ISSN 0097-6326. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ↑ Colton, Craig; Mullins, Haskell (6 June 2003). "Assigned Protection Factors (29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926) - No. 18" (PDF). Federal Register. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 68 (109, Part II): 34061. ISSN 0097-6326. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ↑ Keys, D.R.; Guy, Harry; Axon, M. (6 June 2003). "Assigned Protection Factors (29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926) - No. 27" (PDF). Federal Register. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 68 (109, Part II): 34061. ISSN 0097-6326. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ↑ Hery, Michel; Mario, Villa; Hubert, Genevieve; Martin, Patrick (1991). "Assessment of the performance of respirators". The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. Oxford, UK: The British Occupational Hygiene Society - Oxford University Press. 35 (2): 181–187. doi:10.1093/annhyg/35.2.181. ISSN 0003-4878. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- 1 2 Johnson, Alan; Myers, Warren; Colton, Craig; Birkner, J.S.; Campbell, C.E. (1992). "Review of respirator performance testing in the workplace: issues and concerns". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 53 (11): 705–712. doi:10.1080/15298669291360409. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Coulton, C.E.; Mullins, Haskell (6 June 2003). "Assigned Protection Factors (29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926) - No. 1C" (PDF). Federal Register. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 68 (109, Part II): 34051. ISSN 0097-6326. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ↑ Gaboury, A.; Burd, D.H.; Friar, R.S. (1993). "Workplace Protection Factor Evaluation of Respiratory Protective Equipment in a Primary Aluminum Smelter". Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 8 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1080/1047322X.1993.10388111. ISSN 1047-322X. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- 1 2 Lof, Agneta; Brohede, Christina; Gullstrand, Elisabeth; Lindstrom, Karin; Sollenberg, Jan; Wrangskog, Kent; Hagberg, Mats; Hedman, Birgitta Kolmodin (1993). "The effectiveness of respirators measured during styrene exposure in a plastic boat factory". International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. Springer-Verlag. 65 (1): 29–34. doi:10.1007/BF00586055. ISSN 0340-0131. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ Lee, Byung-Kook; Lee, Choong-Won; Ahn, Kyu-Dong (1993). "The effect of respiratory protection with biological monitoring on the health management of lead workers in a storage battery industry". International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. Springer-Verlag. 65 (Supplement 1): S181–S184. doi:10.1007/BF00381336. ISSN 0340-0131. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ Wallis, George; Menke, Robert; Chelton, Charles (1993). "Workplace field testing of a disposable negative pressure half-mask dust respirator (3M 8710)". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 54 (10): 576–583. doi:10.1080/15298669391355080. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Colton, Craig; Mullins, Haskell; Bidwell, Jeanne (6 June 2003). "Assigned Protection Factors (29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926) - No. 19" (PDF). Federal Register. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 68 (109, Part II): 34066. ISSN 0097-6326. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ↑ Hery, Michel; Meyer, J.P.; Villa, Mario; Hubert, Genevieve; Gerber, J.M.; Hecht, G.; Franc, D.; Herrault, J. (1993–1994). "Measurements of Workplace Protection Factors of Six Negative Pressure Half-Masks". Journal of the International Society for Respiratory Protection. International Society for Respiratory Protection. 11 (3): 15–39. ISSN 0892-6298.

- ↑ Coulton, C.E.; Mullins, Haskell; Bidwell, Jeanne (6 June 2003). "Assigned Protection Factors (29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926) - No. 1B" (PDF). Federal Register. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 68 (109, Part II): 34051. ISSN 0097-6326. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- ↑ Nelson, Thomas (1995). "The Assigned Protection Factor of 10 for Half-mask Respirators". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 56 (7): 717–724. doi:10.1080/15428119591016755. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Popendorf, William; Merchant, James; Leonard, Stephanie; Burmeister, Leon; Olenchock, Stephen (1995). "Respirator Protection and Acceptability Among Agricultural Workers". Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 10 (7): 595–605. doi:10.1080/1047322X.1995.10387652. ISSN 1047-322X. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Myers, Warren; Zhuang, Ziqing (1996). "Field Performance Measurements of Half-Facepiece Respirators—Paint Spraying Operations". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 57 (1): 50–57. doi:10.1080/15428119691015214. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Myers, Warren; Zhuang, Ziqing; Nelson, Thomas (1996). "Field Performance Measurements of Half-Facepiece Respirators—Foundry Operations". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 57 (2): 166–174. doi:10.1080/15428119691015106. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Conroy, Lorraine; Menezes-Lindsay, Rosanne; Sullivan, Paul; Conroy, Salvatore; Forst, Linda (1996). "Lead, Chromium, and Cadmium Exposure during Abrasive Blasting". Archives of Environmental Health: An International Journal. Philadelphia, PA: Taylor & Francis. 51 (2): 95–99. doi:10.1080/00039896.1996.9936000. ISSN 0003-9896. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Nelson, Thomas (1996). "The Assigned Protection Factor According to ANSI". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 57 (8): 735–740. doi:10.1080/15428119691014594. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Riala, Riitta; Riipinen, Hannu (1998). "Respirator and High Efficiency Particulate Air Filtration Unit Performance in Asbestos Abatement". Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 13 (1): 32–40. doi:10.1080/1047322X.1998.10389544. ISSN 1047-322X. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Myers, Warren; Zhuang, Ziqing (1998). "Field Performance Measurements of Half-Facepiece Respirators: Steel Mill Operations". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 59 (11): 789–795. doi:10.1080/15428119891010974. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Limasset, J.C.; Simon, P.; Poirot, P.; Subra, I.; Grzebyk, M. (1999). "Estimation of the percutaneous absorption of styrene in an industrial situation". International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. Springer-Verlag. 72 (1): 46–51. doi:10.1007/s004200050333. ISSN 0340-0131. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ Bancroft, B.; Clayton, Mike; Evans, P.G.; Hughes, A.S. (1999). "Workplace Fit of Full Face Mask Respirators — A New Approach". Journal of the International Society for Respiratory Protection. International Society for Respiratory Protection. 17 (2): 24–54. ISSN 0892-6298.

- ↑ Gobba, F.; Ghittori, S.; Imbriani, M.; Cavalleri, A. (2000). "Evaluation of half-mask respirator protection in styrene-exposed workers". International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. Springer-Verlag. 73 (1): 56–60. doi:10.1007/PL00007938. ISSN 0340-0131. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ Spear, Terry; DuMond, James; Lloyd, Carrie; Vincent, James (2000). "An Effective Protection Factor Study of Respirators Used by Primary Lead Smelter Workers". Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 15 (2): 235–244. doi:10.1080/104732200301746. ISSN 1047-322X. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Weber, R.A.; Mullins, Haskell (2000). "Measuring Performance of a Half-Mask Respirator in a Styrene Environment". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 61 (3): 415–421. doi:10.1080/15298660008984553. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Hanley, Kewin; Lenhart, Steven (2000). "Manganese Dioxide Exposures and Respirator Performance at an Alkaline Battery Plant". Applied Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 15 (7): 542–549. doi:10.1080/10473220050028367. ISSN 1047-322X. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Nelson, Thomas; Wheeler, Teresa; Mustard, Timothy (2001). "Workplace Protection Factors—Supplied Air Hood". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 62 (1): 96–99. doi:10.1080/15298660108984615. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Collia, D.V.; et al. (6 June 2003). "Assigned Protection Factors (29 CFR Parts 1910, 1915, and 1926) - No. 26" (PDF). Federal Register. Department of Labor, Occupational Safety and Health Administration. 68 (109, Part II): 34064. ISSN 0097-6326. Retrieved 16 June 2016.

- 1 2 3 Ming-Tsang, Wu (2002). "Assessment of the Effectiveness of Respirator Usage in Coke Oven Workers". American Industrial Hygiene Association Journal. Akron, Ohio: AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 63 (1): 72–75. doi:10.1080/1542811020898469. ISSN 1542-8117. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- 1 2 Clayton, Mike; Bancroft, B.; Rajan-Sithamparanadarajah, Bob (2002). "A Review of Assigned Protection Factors of Various Types and Classes of Respiratory Protective Equipment with Reference to their Measured Breathing Resistances". The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. Oxford, UK: The British Occupational Hygiene Society - Oxford University Press. 46 (6): 537–547. doi:10.1093/annhyg/46.6.537. ISSN 0003-4878. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ HSE (2013). Respiratory protective equipment at work. A practical guide (PDF) (4 ed.). Health and Safety Executive. ISBN 978 0 7176 6454 2.

- ↑ Han, Don-Hee (2002). "Correlations between Workplace Protection Factors and Fit Factors for Filtering Facepieces in the Welding Workplace". 40 (4). Tokyo, Japan: National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health: 328–334. doi:10.2486/indhealth.40.328. ISSN 1880-8026. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- 1 2 3 Nicas, Mark; Neuhaus, John (2004). "Variability in Respiratory Protection and the Assigned Protection Factor". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 1 (2): 99–109. doi:10.1080/15459620490275821. ISSN 1545-9632. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Bidwell, Jeanne; Janssen, Larry (2004). "Workplace Performance of an N95 Respirator in a Concrete Block Manufacturing Plant". Journal of the International Society for Respiratory Protection. International Society for Respiratory Protection. 21: 94–102. ISSN 0892-6298.

- 1 2 3 Shu-An, Lee; Grinshpun, Sergey; Adhikari, Atin; Weixin, Li; Mckay, Roy; Maynard, Andrew; Reponen, Tiina (2005). "Laboratory and Field Evaluation of a New Personal Sampling System for Assessing the Protection Provided by the N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirators against Particles". The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. Oxford, UK: The British Occupational Hygiene Society - Oxford University Press. 49 (3): 245–257. doi:10.1093/annhyg/49.3.245. ISSN 0003-4878. Retrieved 10 July 2016.

- ↑ Shu-An, Lee; Adhikari, Atin; Grinshpun, Sergey; Mckay, Roy; Shukla, Rakesh; Zeigler, Haoyue Li; Reponen, Tiina (2005). "Respiratory Protection Provided by N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirators Against Airborne Dust and Microorganisms in Agricultural Farms". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 2 (11): 577–585. doi:10.1080/15459620500330583. ISSN 1545-9632. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- 1 2 Janssen, Larry; Bidwell, Jeanne (2007). "Performance of a Full Facepiece, Air-Purifying Respirator Against Lead Aerosols in a Workplace Environment". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 4 (2): 123–128. doi:10.1080/15459620601128845. ISSN 1545-9632. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- 1 2 Chang, Fu-Kuei; Chen, Mei-Lien; Cheng, Shu-Fang; Shih, Tung-Sheng; Mao, I-Fang (2007). "Evaluation of dermal absorption and protective effectiveness of respirators for xylene in spray painters". International Archives of Occupational and Environmental Health. Springer-Verlag. 81 (2): 145–150. doi:10.1007/s00420-007-0197-9. ISSN 0340-0131. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ Cramp, Kenny (2007). "Statistical Issues with Respect to Workplace Protection Factors for Respirators". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 4 (3): 208–214. doi:10.1080/15459620601169526. ISSN 1545-9632. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Janssen, Larry; Nelson, Thomas; Cuta, Karen (2007). "Workplace Protection Factors for an N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirator". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 4 (9): 698–707. doi:10.1080/15459620701517764. ISSN 1545-9632. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Janssen, Larry; Bidwell, Jeanne; McCullough, Nicole (2007). "Performance of an N95 Filtering Facepiece Respirator in a Grinding Operation" (PDF). Journal of the International Society for Respiratory Protection. International Society for Respiratory Protection. 24: 21–30. ISSN 0892-6298.

- ↑ Janssen, Larry; Bidwell, Jeanne; Cuta, Karen; Nelson, Thomas (2008). "Workplace Performance of a Hood-Style Supplied-Air Respirator". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 5 (7): 438–443. doi:10.1080/15459620802115930. ISSN 1545-9632. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Janssen, Larry; McCullough, Nicole (2009). "Elastomeric, Half-Facepiece, Air-Purifying Respirator Performance in a Lead Battery Plant". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 7 (1): 46–53. doi:10.1080/15459620903373537. ISSN 1545-9632. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Cho, Kyungmin Jacob; Jones, Susan; Jones, Gordon; McKay, Roy; Grinshpun, Sergey; Dwivedi, Alok; Shukla, Rakesh; Singh, Umesh; Reponen, Tiina (2010). "Effect of Particle Size on Respiratory Protection Provided by Two Types of N95 Respirators Used in Agricultural Settings". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Hygiene. AIHA & ACGIH - Taylor & Francis. 7 (11): 622–627. doi:10.1080/15459624.2010.513910. ISSN 1545-9632. Retrieved 15 July 2016.

- ↑ Crawford, Joanne; Dixon, Ken; Miller, Brian and John W. Cherrie (2012). A review of the effectiveness of respirators in reducing exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons for coke oven workers. Research Report TM/12/01. Edinburgh, UK: Institute of Occupational Medicine. p. 67.

- ↑ Crawford, Joanne; Dixon, Ken; Miller, Brian; Cherrie, John (2014). "A Review of the Effectiveness of Respirators in Reducing Exposure to Polycyclic Aromatic Hydrocarbons for Coke Oven Workers". The Annals of Occupational Hygiene. Oxford, UK: The British Occupational Hygiene Society - Oxford University Press. 58 (8): 943–954. doi:10.1093/annhyg/meu048. ISSN 0003-4878. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ Koivisto, Antti; Aromaa, Mikko; Koponen, Ismo; Fransman, Wouter; Jensen, Keld; Makela, Jyrki; Hameri, Kaarle (2015). "Workplace performance of a loose-fitting powered air purifying respirator during nanoparticle synthesis". Journal of Nanoparticle Research. Springer-Verlag. 17 (4): 177–184. doi:10.1007/s11051-015-2990-9. ISSN 1388-0764. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ European Committee for Standardization (2005). "6 Verfahren zur Gefahrdungsbeurteilung". In Technischen Komitee CEN/TC 79 "Respiratory protective devices". DIN EN 529:2006 "Atemschutzgerate - Empfehlungen fur Auswahl, Einsatz, Pflege und Instandhaltung - Leitfaden" (in German) (Deutsche Fassung EN 529:2005 ed.). Brussel, rue de Stassart, 36: Deutsche Gremium ist NA 027-02-04 AA «Atemgerate fur Arbeit und Rettung» im Normenausschuss Feinmechanik und Optik (NAFuO). p. 50.

- ↑ Howie, Robin M.; Walton, W.H. (1981). "Practical Aspects of the Use of Respirators in the British Coal Mines". In Brian Ballantyne & Paul Schwabe. Respiratory Protection. Principles and Applications. London, New York: Chapman & Hall. pp. 287–298. ISBN 0412227509.

- ↑ Kissell, Fred N. (2003). "Types of respirators used in mines and tunnels". Handbook for Dust Control in Mining. Information Circular 9465. DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2003-147. Pittsburgh, PA: National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. pp. 122–124. Retrieved 16 July 2016.

- ↑ Gorodinski, Semyon (1979). "Introduction". [Personal protective equipement from radioactive substances] (СМ Городинский. Средства индивидуальной защиты от радиоактивных веществ) (in Russian) (3 ed.). Moscow: The state Committee of the USSR Council of Ministers on the use of atomic energy, "Атомиздат" publ. pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Petryanov, Igor; Kashcheev, Victor; et al. (2015). ["Lepestok". Filterring facepieces] (in Russian) (2 ed.). Moscow: Nauka. p. 320. ISBN 978-5-02-039145-1.

- 1 2 Hoover, Mark D.; Lackey, Jack R.; Vargo, George J. (2001). "Results and Discussion". Independent Evaluation of The Lepestok Filtering Facepiece Respirator (PDF). PNNL-13581; LRRI-20001202. Albuquerque, NM: Lovelace Respiratory Research Institute, Pacific Northwest National Laboratory (U.S. Department of Energy). pp. 13–20. Retrieved 16 July 2016.