Nationality law of the Republic of China

| Nationality law of the Republic of China | |||||||

| |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 中華民國國籍法 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 中华民国国籍法 | ||||||

| |||||||

The Nationality Law of the Republic of China[1] defines and regulates nationality of the Republic of China. It was first promulgated by the Nationalist Government on February 5, 1929 and revised by the Taipei-based Legislative Yuan in 2000, 2001, and 2006.

The Act, like the Constitution of the Republic of China, makes no provision regarding citizenship. Citizenship rights in the Republic of China are currently restricted to persons with household registration in the Taiwan Area. The Act sets to define persons in terms of nationality (國籍), terming them as "nationals" (國民) rather than "citizens" (公民), a term that does not appear in the act.

Nationality

Republic of China nationality generally follows jus sanguinis. The law spells out four criteria, any one of which may be met to qualify for nationality:

- A person whose father or mother is, at the time of his (her) birth, a national of the Republic of China.

- A person born after the death of his (her) father or mother who was, at the time of his (her) death, a national of the Republic of China.

- A person born in the territory of the Republic of China and whose parents are both unknown or are stateless.

- A naturalized person.

In the original version of the law nationality could only be passed from father to child. However, the law was revised in 2000 to allow citizenship to be passed on from either parent, taking effect on those born after February 9, 1980 (those under age 20 at the time of the promulgation).

Citizenship

In practice, exercise of most citizenship benefits, such as suffrage, labour rights, and access to national health insurance, requires possession of the Republic of China National Identification Card, which is only issued to persons with household registration in the Taiwan Area aged 14 and older. Note that children of ROC nationals who were born abroad are eligible for ROC passports and therefore considered to be nationals, but often they do not hold a household registration so are referred to as "unregistered nationals" in statute. These ROC nationals have no automatic right to stay in Taiwan, nor do they have working rights, voting rights, etc. In a similar fashion, some British passport holders do not have the right of abode in the UK (see British nationality law). Unregistered nationals can obtain a Republic of China National Identification Card only by settling in Taiwan for one year.

Dual nationality and naturalization

Article 9 of the ROC Nationality Act requires prospective naturalized citizens to first renounce their previous nationality, possibly causing those persons to become stateless if they then fail to obtain ROC nationality.[2] The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees has noted that this has caused thousands of Vietnamese women to become stateless.[3] Article 9 does not apply to overseas Chinese holding foreign nationality who seek to exercise ROC nationality. Such persons do not need to naturalize because they are already legally ROC nationals.

The Act does not restrict ROC nationals from becoming dual nationals of other countries. Dual nationals are however restricted by Article 20 from holding most public offices in Taiwan. Indeed, many immigrants to Taiwan give up their original nationality, obtain ROC nationality, then apply again for their original nationality—which some countries will restore, some after a waiting period. (Notably, the United States government has no such procedure.) This entire process is fully legal under ROC law, though statistics are not available regarding how many people do this. The Act also permits former nationals of the ROC to apply for restoration of their nationality.

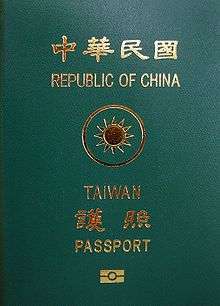

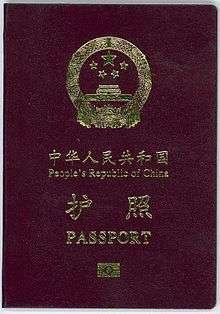

However, by Article 9-1, "[t]he people of the Taiwan Area may not have household registrations in the Mainland Area or hold passports issued by the Mainland Area." Republic of China nationals are not recognised to be dual nationals of the People's Republic of China (PRC), which the Republic of China Government does not recognise. If they obtain the passport of the PRC or household registration within mainland China, they will be deprived of their ROC Passport.[4] [5]

|  |

| Nationals of the Republic of China with household registrations in the Taiwan Area are eligible for the Republic of China passport (left), and will lose the household registrations in the Taiwan Area, along with their ROC passport, upon holding the People's Republic of China passport (right). They are different and mutually exclusive in law; most people living in Taiwan only will and only can choose one of these two to identify themselves by current laws.[6] | |

Status of mainland Chinese and overseas Chinese

The Republic of China's official borders encompass all of territories governed by the People's Republic of China and persons of these territories are considered under ROC law to be nationals of the Republic of China. Thus, if the residents of mainland China want to travel to the Taiwan Area, they must do so using the Entry Permit of Mainland Residents to the Taiwan Area and residents of Hong Kong and Macau must enter using the Entry Permit of HK and Macau Residents to the Taiwan Area. PRC passports, HKSAR passports, Macau SAR passports, and BN(O) passports are not stamped by Taiwan immigration officers. Mongolia is also within the ROC's official borders, but since 2002, the government has extended recognition to the Mongolian government and permitted citizens of Mongolia to use their passports to enter Taiwan in lieu of an entry permit.

If the residents of mainland China seek to settle permanently in Taiwan and gain citizenship rights, they do not naturalize like citizens of foreign countries. Instead, they merely can establish household registration, which in practice takes longer and is more complicated than naturalization.

Republic of China passports are also issued to overseas Chinese, irrespective of whether they have lived or even set foot in Taiwan. The rationale behind this extension of the principle of jus sanguinis to almost all Chinese regardless of their countries of residence, as well as the recognition of dual citizenships, is to acknowledge the support given by overseas Chinese historically to the Kuomintang regime, particularly during the Republican Revolution of 1911. The type of passport issued to these individuals is called "Overseas Chinese Passport" of the Republic of China (僑民護照) and it is different than the type of passport issued to nationals that possess a national identification card with the former having far more restrictions than the latter. For instance, overseas Chinese passport holders are required to apply for a visa to enter the Schengen area, whereas no visa is required for the regular passport holders. See the passport article for more information about this practice.

But for the residents of mainland China, Hong Kong, and Macau, only after gaining permanent resident status abroad, or otherwise establishing a period of residency defined by the regulations, they become eligible for a Republic of China passport but do not gain benefits of citizenship.

Post-World War 2 controversy

According to the 1895 Treaty of Shimonoseki, Taiwan belonged to Japan, but people living in Taiwan were given "the opportunity to choose their nationality" by either leaving or staying within two years of the treaty being signed.[8] On the other side, the nationality law of ROC was first promulgated by the Nationalist Government on February 5, 1929, when Taiwan was still under Japanese rule. However, in 1946, the ROC government announced that the people living in Taiwan had "regained" their status as ROC nationals, which gave rise to diplomatic protests from the UK and the US.[9] Up to the present day, this Nationality Law has been revised by the Taipei-based Legislative Yuan in 2000, 2001, and 2006. The inclusion of native Taiwanese people within its scope of application has also been controversial. Some opponents of the ROC's sovereignty over Taiwan argue that the law has "forced" citizenship onto Taiwanese aborigines.

Nationality recognition by international organizations and customs officials

According to the standards and regulations of most international organizations, "Republic of China" is not a recognized nationality in the international community. With reference to ISO 3166-1 of the The International Standards Organization, the proper nationality designation for persons domiciled in Taiwan is not ROC, but rather TWN. This three-letter abbreviation of TWN is also the official designation adopted by the International Civil Aviation Organization [10] for use on a machine-readable travel document when dealing with entry/exit procedures at customs authorities in all nations of the world.

References

- ↑ "Nationality Act".

- ↑ "Not allowed to be Taiwanese". jidanni.org. Retrieved 2007-09-05.

- ↑ "The Excluded: The strange hidden world of the stateless", UNHCR Refugees Magazine Issue 147.

"Divorce leaves some Vietnamese women broken-hearted and stateless", 14 February 2007, unhcr.com Archived May 9, 2008, at the Wayback Machine. - ↑ "臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例".

- ↑ "Act Governing Relations between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area".

- ↑ "臺灣地區與大陸地區人民關係條例".

- ↑ "Act Governing Relations between the People of the Taiwan Area and the Mainland Area".

- ↑ Hsueh, Hua-yuan, ed. (2007). 臺灣地位關係文書 (in Chinese). Taipei: 日創社文化. ISBN 9789866900044.

- ↑ Chen, Yi-nan (20 January 2011). "ROC forced citizenship on unwary Taiwanese". Taipei Times. p. 8. Retrieved 2011-01-25.

- ↑ "Appendix 1, Three Letter Codes: Codes for designation of nationality, place of birth or issuing State/authority". Machine Readable Travel Documents (PDF). Section IV, Part 3, Volume 1 (Third ed.). Montreal, Quebec, Canada: International Civil Aviation Organization. 2008. ISBN 978-92-9231-139-1. Retrieved 2014-02-18.

External links

- Applying for dual nationality as a UK citizen

- National Immigration Service

- 碩士論文:我國國籍法制與實施現況之研究 (Taiwanese Mandarin)