Regular chain

In computer algebra, a regular chain is a particular kind of triangular set in a multivariate polynomial ring over a field. It enhances the notion of characteristic set.

Introduction

Given a linear system, one can convert it to a triangular system via Gaussian elimination. For the non-linear case, given a polynomial system F over a field, one can convert (decompose or triangularize) it to a finite set of triangular sets, in the sense that the algebraic variety V(F) is described by these triangular sets.

A triangular set may merely describe the empty set. To fix this degenerated case, the notion of regular chain was introduced, independently by Kalkbrener (1993), Yang and Zhang (1994). Regular chains also appear in Chou and Gao (1992). Regular chains are special triangular sets which are used in different algorithms for computing unmixed-dimensional decompositions of algebraic varieties. Without using factorization, these decompositions have better properties that the ones produced by Wu's algorithm. Kalkbrener's original definition was based on the following observation: every irreducible variety is uniquely determined by one of its generic points and varieties can be represented by describing the generic points of their irreducible components. These generic points are given by regular chains.

Examples

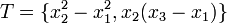

Denote Q the rational number field. In Q[x1, x2, x3] with variable ordering x1 < x2 < x3,

is a triangular set and also a regular chain. Two generic points given by T are (a, a, a) and (a, -a, a) where a is transcendental over Q. Thus there are two irreducible components, given by { x2 - x1, x3 - x1 } and { x2 + x1, x3 - x1 }, respectively. Note that: (1) the content of the second polynomial is x2, which does not contribute to the generic points represented and thus can be removed; (2) the dimension of each component is 1, the number of free variables in the regular chain.

Formal definitions

The variables in the polynomial ring

are always sorted as x1 < ... < xn.

A non-constant polynomial f in  can be seen as a univariate polynomial in its greatest variable.

The greatest variable in f is called its main variable, denoted by mvar(f). Let u be

the main variable of f and write it as

can be seen as a univariate polynomial in its greatest variable.

The greatest variable in f is called its main variable, denoted by mvar(f). Let u be

the main variable of f and write it as

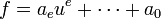

,

,

where e is the degree of f w.r.t. u and  is

the leading coefficient of f w.r.t. u. Then the initial of f

is

is

the leading coefficient of f w.r.t. u. Then the initial of f

is  and e is its main degree.

and e is its main degree.

- Triangular set

A non-empty subset T of  is a triangular set,

if the polynomials in T are non-constant and have distinct main variables.

Hence, a triangular set is finite, and has cardinality at most n.

is a triangular set,

if the polynomials in T are non-constant and have distinct main variables.

Hence, a triangular set is finite, and has cardinality at most n.

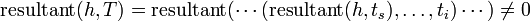

- Regular chain

Let T = {t1, ..., ts} be a triangular set such that

mvar(t1) < ... < mvar(ts),

be the initial of ti and h be the product of hi's.

Then T is a regular chain if

be the initial of ti and h be the product of hi's.

Then T is a regular chain if

-

,

,

where each resultant is computed with respect to the main variable of ti, respectively. This definition is from Yang and Zhang, which is of much algorithmic flavor.

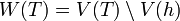

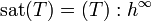

- Quasi-component and saturated ideal of a regular chain

The quasi-component W(T) described by the regular chain T is

, that is,

, that is,

the set difference of the varieties V(T) and V(h). The attached algebraic object of a regular chain is its saturated ideal

.

.

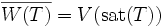

A classic result is that the Zariski closure of W(T) equals the variety defined by sat(T), that is,

,

,

and its dimension is n - |T|, the difference of the number of variables and the number of polynomials in T.

- Triangular decompositions

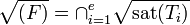

In general, there are two ways to decompose a polynomial system F. The first one is to decompose lazily, that is, only to represent its generic points in the (Kalkbrener) sense,

-

.

.

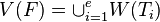

The second is to describe all zeroes in the Lazard sense,

-

.

.

There are various algorithms available for triangular decompositions in either sense.

Properties

Let T be a regular chain in the polynomial ring R.

- The saturated ideal sat(T) is an unmixed ideal with dimension n − |T|.

- A regular chain holds a strong elimination property in the sense that:

-

![\mathrm{sat}(T \cap k[x_1, \ldots , x_i]) = \mathrm{sat}(T) \cap k[x_1,\ldots , x_i]](../I/m/220f47e1b403c41711243e6e41e91287.png) .

.

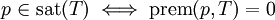

- A polynomial p is in sat(T) if and only if p is pseudo-reduced to zero by T, that is,

-

.

. - Hence the membership test for sat(T) is algorithmic.

- A polynomial p is a zero-divisor modulo sat(T) if and only if

and

and  .

.

- Hence the regularity test for sat(T) is algorithmic.

- Given a prime ideal P, there exists a regular chain C such that P = sat(C).

- If the first element of a regular chain C is an irreducible polynomial and the others are linear in their main variable, then sat(C) is a prime ideal.

- Conversely, if P is a prime ideal, then, after almost all linear changes of variables, there exists a regular chain C of the preceding shape such that P = sat(C).

- A triangular set is a regular chain if and only if it is a Ritt characteristic set of its saturated ideal.

See also

- Wu's method of characteristic set

- Gröbner basis

- RegularChains, a software to compute with regular chains

- Regular semi-algebraic system

- Triangular decomposition

Further references

- P. Aubry, D. Lazard, M. Moreno Maza. On the theories of triangular sets. Journal of Symbolic Computation, 28(1–2):105–124, 1999.

- F. Boulier and F. Lemaire and M. Moreno Maza. Well known theorems on triangular systems and the D5 principle. Transgressive Computing 2006, Granada, Spain.

- E. Hubert. Notes on triangular sets and triangulation-decomposition algorithms I: Polynomial systems. LNCS, volume 2630, Springer-Verlag Heidelberg.

- F. Lemaire and M. Moreno Maza and Y. Xie. The RegularChains library. Maple Conference 2005.

- M. Kalkbrener: Algorithmic Properties of Polynomial Rings. J. Symb. Comput. 26(5): 525–581 (1998).

- M. Kalkbrener: A Generalized Euclidean Algorithm for Computing Triangular Representations of Algebraic Varieties. J. Symb. Comput. 15(2): 143–167 (1993).

- D. Wang. Computing Triangular Systems and Regular Systems. Journal of Symbolic Computation 30(2) (2000) 221–236.

- Yang, L., Zhang, J. (1994). Searching dependency between algebraic equations: an algorithm applied to automated reasoning. Artificial Intel ligence in Mathematics, pp. 14715, Oxford University Press.

![R = k[x_1, \ldots, x_n]](../I/m/42330c42050d9e31dc06975acc3e5ed4.png)