Reggaeton

| Reggaeton | |

|---|---|

| Stylistic origins | |

| Typical instruments | |

| Subgenres | |

| Fusion genres | |

| Regional scenes | |

Reggaetón (also known as reggaeton, reggaetón, and reguetón[1]) is a musical genre which originated in Puerto Rico during the late 1990s. It is influenced by hip hop and Latin American and Caribbean music. Vocals include rapping and singing, typically in Spanish.

Etymology

The word "reggaeton" (from the Puerto Rican tradition of combining a word with the suffix -tón) was first used in 1995, when DJ Nelson listed it as a potential name for an upcoming album.[2] Although there are several Spanish spellings, Fundéu BBVA recommends reguetón; "reggaeton" or "reggaetón" should appear in italics if used.[1][3]

History

Often mistaken for reggae or reggae en español, reggaeton is a younger genre which originated in the clubs of San Juan, Puerto Rico in 1991. It became known as "underground" music, due to its circulation through informal networks and performances at unofficial venues. DJ Playero and DJ Nelson were inspired by hip hop and Latin American music to produce "riddims," the first reggaeton tracks. As Caribbean and African-American music gained momentum in Puerto Rico, reggae rap in Spanish marked the beginning of the Boricua underground and was a creative outlet for many young people. This created an inconspicuous-yet-prominent underground youth culture which sought to express itself. As a youth culture existing on the fringes of society and the law, it has often been criticized. The Puerto Rican police launched a campaign against underground music by confiscating cassette tapes from music stores under penal obscenity codes, levying fines and demoralizing rappers in the media.[4] Bootleg recordings and word of mouth became the primary means of distribution for this music until 1998, when it coalesced into modern reggaeton. The genre's popularity increased when it was discovered by international audiences during the early 2000s.[5]

The new genre, simply called "underground", had explicit lyrics about drugs, violence, poverty, friendship, love and sex. These themes, depicting the troubles of inner-city life, can still be found in reggaeton. "Underground" music was recorded in marquesinas (Puerto Rican open garages) and distributed in the streets on cassettes. The marquesinas were crucial to the development of Puerto Rico's underground scene because of the state's "fear of losing the ability to manipulate 'taste'".[4] Marquesinas were often in "housing complexes such as Villa Kennedy and Jurutungo".[4] Despite being recorded in housing projects, most of the marquesinas were good quality (which helped increase their popularity among Puerto Rican youth of all social classes). The availability and quality of the cassettes led to reggaeton's popularity, which crossed socioeconomic barriers in the Puerto Rican music scene. The most popular cassettes in the early 1990s were DJ Negro's The Noise I and II and DJ Playero's 37 and 38. Gerardo Cruet (who created the recordings) spread the genre from the marginalized residential areas into other sectors of society, particularly private schools.

By the mid-1990s, "underground" cassettes were being sold in music stores. The genre caught up to middle-class youth, and found its way into the media. By this time, Puerto Rico had several clubs dedicated to the underground scene; Club Rappers in Carolina and PlayMakers in Puerto Nuevo were the most notable. Bobby "Digital" Dixon's "Dem Bow" production was played in clubs. Underground music was not originally intended to be club music. In South Florida, DJ Laz and Hugo Diaz of the Diaz Brothers were popularizing the genre from Palm Beach to Miami.

Underground music in Puerto Rico was harshly criticized. In February 1995, there was a government-sponsored campaign against underground music and its cultural influence. Puerto Rican police raided six record stores in San Juan,[6] hundreds of cassettes were confiscated and fines imposed in accordance with Laws 112 and 117 against obscenity.[4] The Department of Education banned baggy clothing and underground music from schools.[7] For months after the raids local media demonized rappers, calling them "irresponsible corrupters of the public order."[4]

In 1995 DJ Negro released The Noise 3 with a mockup label reading, "Non-explicit lyrics". The album had no cursing until the last song. It was a hit, and underground music continued to seep into the mainstream. Senator Velda González of the Popular Democratic Party and the media continued to view the movement as a social nuisance.[8]

During the mid-1990s, the Puerto Rican police and National Guard confiscated reggaeton tapes and CDs to get "obscene" lyrics out of the hands of consumers.[9] Schools banned hip hop clothing and music to quell reggaeton's influence. In 2002, Senator González led public hearings to regulate the sexual "slackness" of reggaeton lyrics. Although the effort did not seem to negatively affect public opinion about reggaeton, it reflected the unease of the government and the upper social classes with what the music represented. Because of its often sexually-charged content and its roots in poor, urban communities, many middle- and upper-class Puerto Ricans found reggaeton threatening, "immoral, as well as artistically deficient, a threat to the social order, apolitical".[7]

Despite the controversy, reggaeton slowly gained acceptance as part of Puerto Rican culture— helped, in part, by politicians (including González) who began to use reggaeton in election campaigns to appeal to younger voters in 2003.[7] Puerto Rican mainstream acceptance of reggaeton has grown and the genre has become part of popular culture, including a 2006 Pepsi commercial with Daddy Yankee[10] and PepsiCo's choice of Ivy Queen as musical spokesperson for Mountain Dew.[11] Other examples of greater acceptance in Puerto Rico are religiously- and educationally=influenced lyrics; Reggae School is a rap album produced to teach math skills to children, similar to School House Rock.[12] Reggaeton expanded when other producers, such as DJ Nelson and DJ Eric, followed DJ Playero. During the 1990s, Ivy Queen's 1996 album En Mi Imperio DJ Playero's Playero 37 (introducing Daddy Yankee) and The Noise: Underground, The Noise 5 and The Noise 6 were popular in Puerto Rico and the Dominican Republic. Singers Don Chezina, Tempo, Eddie Dee, Baby Rasta & Gringo and Lito & Polaco were also popular.

The name "reggaeton" became prominent during the early 2000s, characterized by the dembow beat. It was coined in Puerto Rico to describe a unique fusion of Puerto Rican music.[5] Reggaeton is currently popular throughout Latin America. It increased in popularity with Latino youth in the United States when DJ Joe and DJ Blass worked with Plan B and Speedy[13] on Reggaeton Sex, Sandunguero and Fatal Fantassy.

2004: Crossover

In 2004, reggaeton became popular in the United States and Europe. Tego Calderón was receiving airplay in the U.S., and the music was popular among youth. Daddy Yankee's El Cangri.com became popular that year in the country, as did Héctor & Tito. Luny Tunes and Noriega's Mas Flow, Yaga & Mackie's Sonando Diferente, Tego Calderón's El Abayarde, Ivy Queen's Diva, Zion & Lennox's Motivando a la Yal and the Desafío compilation were also well-received. Rapper N.O.R.E. released a hit single, "Oye Mi Canto". Daddy Yankee released Barrio Fino and a hit single, "Gasolina". Tego Calderón recorded the singles "Pa' Que Retozen" and "Guasa Guasa". Don Omar was popular, particularly in Europe, with "Pobre Diabla" and "Dale Don Dale".[14] Other popular reggaeton artists include Tony Dize, Angel & Khriz, Nina Sky, Dyland & Lenny, RKM & Ken-Y, Julio Voltio, Calle 13, Héctor Delgado, Wisin & Yandel and Tito El Bambino. In late 2004 and early 2005 Shakira recorded "La Tortura" and "La Tortura – Shaketon Remix" for her album, Fijación Oral Vol. 1 (Oral Fixation Vol. 1), popularizing reggaeton in North America, Europe and Asia. Musicians began to incorporate bachata into reggaeton,[15] with Ivy Queen releasing singles ("Te He Querido, Te He Llorado" and "La Mala") featuring bachata's signature guitar sound, slower, romantic rhythms and emotive singing style.[15] Daddy Yankee's "Lo Que Paso, Paso" and Don Omar's "Dile" are also bachata-influenced. In 2005 producers began to remix existing reggaeton music with bachata, marketing it as bachaton: "bachata, Puerto Rican style".[15]

2006–2010: Topping the charts

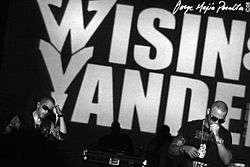

In May 2006 Don Omar's King of Kings was the highest-ranking reggaeton LP to date on the U.S. charts, debuting atop the Top Latin Albums chart and peaking at number seven on the Billboard 200 chart. Omar's single, "Angelito", topped the Billboard Latin Rhythm Radio Chart.[16] He broke Britney Spears' in-store-appearance sales record at Downtown Disney's Virgin music store. In June 2007 Daddy Yankee's El Cartel III: The Big Boss set a first-week sales record for a reggaeton album, with 88,000 copies sold.[17] It topped the Top Latin Albums and Top Rap Albums charts, the first reggaeton album to do so on the latter. The album peaked at number nine on the Billboard 200, the second-highest reggaeton album on the mainstream chart.[18] The third-highest-ranking reggaeton album was Wisin & Yandel's Wisin vs. Yandel: Los Extraterrestres, which debuted at number 14 on the Billboard 200 and number one on the Top Latin Albums chart later in 2007.[19] In 2008 Daddy Yankee soundtrack to his film, Talento de Barrio, debuted at number 13 on the Billboard 200 chart. It peaked at number one on the Top Latin Albums chart, number three on Billboard's Top Soundtracks and number six on the Top Rap Albums chart.[18] In 2009, Wisin & Yandel's La Revolucion debuted at number seven on the Billboard Hot 100, number one on the Top Latin Albums and number three on the Top Rap Albums charts.

Characteristics

Rhythm

The dembow riddim was created by Jamaican dancehall producers during the late 1980s and early 1990s. Also known as "son bow", dembow consists of a kick drum, kickdown drum, palito, snare drum, timbal, timballroll and (sometimes) a high-hat cymbal. Dembow's percussion pattern was influenced by dancehall and other West Indian music (soca, calypso and cadence); this gives dembow a pan-Caribbean flavor. Steely & Clevie, creators of the Poco Man Jam riddim, are usually credited with the creation of dembow.[20] At its heart is the 3+3+2 (tresillo) rhythm, complemented by a bass drum in 4/4 time.[21]

|

"Dem Bow riddim"

Three dembow rhythms |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

The riddim was first highlighted by Shabba Ranks in "Dem Bow", from his 1991 album Just Reality. Dembow is created with a drum machine. During the late 1970s, dancehall music was revolutionized by the drum machine and many dancehall producers used them to create different dancehall riddims. Dembow's role in reggaeton is a basic building block, a skeletal sketch in percussion.

Reggaeton dembow also incorporates Bam Bam, Hot This Year, Poco Man Jam, Fever Pitch, Red Alert, Trailer Reloaded and Big Up riddims, and several samples are often used. Newer reggaeton hits incorporate a lighter, electrified version of the riddim. Examples are "Pa' Que la Pases Bien" and "Quiero Bailar", which uses the Liquid riddim.[22]

Lyrics and themes

Reggaeton lyrical structure resembles that of hip hop. Although most reggaeton artists recite their lyrics rapping (or resembling rapping) rather than singing, many alternate rapping and singing. Reggaeton uses traditional verse-chorus-bridge pop structure. Like hip hop, reggaeton songs have a hooks which is repeated throughout the song. Latino ethnic identity is a common musical, lyrical and visual theme.

Unlike hip-hop CDs, reggaeton discs generally do not have parental advisories. An exception is Daddy Yankee's Barrio Fino en Directo (Barrio Fino Live), whose live material (and Snoop Dogg in "Gangsta Zone") were labeled explicit. Artists such as Alexis & Fido circumvent radio and television censorship by sexual innuendo and lyrics with double meanings. Some songs have raised concerns about their depiction of women.[23] Although reggaeton began as a mostly-male genre, the number of women artists has been a slowly increasing and include the "Queen of Reggaeton", Ivy Queen,[24] Mey Vidal, K-Narias, Adassa, La Sista and Glory.

Dance

Sandungueo, or perreo, is a dance associated with reggaeton which emerged during the early 1990s in Puerto Rico. It focuses on grinding, with one partner facing the back of the other (usually male behind female).[25] Another way of describing this dance is "back-to-front", where the woman presses her rear into the pelvis of her partner to create sexual stimulation. Since traditional couple dancing is face-to-face (such as square dancing and the waltz), reggaeton dancing initially shocked observers with its sensuality but was featured in several music videos.[26] It is known as daggering, grinding or juking in the U.S.[27]

Popularity

Latin America

Reggaeton is popular in Puerto Rico, Cuba, Panama, the Dominican Republic, El Salvador, Honduras, Mexico, Guatemala, Colombia, Costa Rica, Venezuela and Peru. A staple of parties and events, it complements the common mix of merengue, bachata, salsa and electronic music.

United States

The New York-based rapper N.O.R.E. (also known as Noreaga) produced Nina Sky's 2004 hit "Oye Mi Canto", which featured Tego Calderón and Daddy Yankee, and reggaeton became popular in the U.S.[28] Daddy Yankee then caught the attention of many hip-hop artists with his song, "Gasolina",[28] and that year XM Radio introduced its reggaeton channel, Fuego (XM). Although XM Radio removed the channel in December 2007 from home and car receivers, it can still be streamed from the XM Satellite Radio website. Reggaeton is the foundation of a Latin-American commercial-radio term, Hurban,[28] a combination of "Hispanic" and "urban" used to evoke the musical influences of hip hop and Latin American music. Reggaeton, which evolved from hip hop and reggae, has helped Latin-Americans contribute to urban American culture and keep many aspects of their Hispanic heritage. The music relates to American socioeconomic issues (including gender and race), in common with hip hop.[28]

Europe

Although reggaeton is less popular in Europe than it is in Latin America, it appeals to Latin American immigrants (especially in Spain).[29] A Spanish media custom, "La Canción del Verano" ("The Summer Song"), in which one or two songs define the season's mood, was the basis of the popularity of reggaeton songs such as Panamanian rapper Lorna's "Papi Chulo (Te Traigo el Mmm)" in 2003 and "Baila Morena" by Héctor & Tito and Daddy Yankee's "Gasolina" in 2005.

Asia

In the Philippines, reggaeton artists primarily use the Filipino language instead of Spanish or English.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Reggaeton. |

| Look up reggaeton in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

References

- 1 2 "Reguetón". Fundéu BBVA. Retrieved 2012-01-20. "The adaptation 'reguetón' is appropriate and already has a certain use. Therefore it is the recommended form. If the original form is used, it would be written in italics, although since it is a mix of an English word and a Spanish one, there are reasons to write it with tilde and without it (problem solved by the completely adapted form)."

- ↑ "1:53 - DJ NELSON - INTERVIEW WITH URBAN FLOW UK - YouTube". YouTube. 2011-10-25. Retrieved 2016-04-11.

- ↑ "Ya No Sería 'Reggaetón' Sino 'Reguetón'". El Mundo. Retrieved 2012-01-20. "The music genre Puerto Ricans Daddy Yankee, Don Omar and Calle 13 are spreading through the world has a name; it is pronounced 'reguetón', but there is no consensus of how to write it in Spanish; the Puerto Rican Academy of the Spanish Language will propose that it be written how it is said."

- 1 2 3 4 5 Mayra Santos, "Puerto Rican Underground", Centro vol. 8 1 & 2 (1996), p. 219-231.

- 1 2 Wayne Marshall (2006-01-19). "Rise of Reggaetón". The Phoenix. Retrieved 2006-07-24.

- ↑ Sara Corbett (2006-02-05). "The King of Reggaetón". The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-01-30.

- 1 2 3 Frances Negrón-Muntaner and Raquel Z. Rivera. "Reggaeton Nation". Archived from the original on 2007-12-21. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- ↑ Hilda Garcia and Gonzalo Salvador. "Reggaeton: The Emergence of a New Rhythm". Archived from the original on 2005-01-15. Retrieved 2007-06-23.

- ↑ John Marino, "Police Seize Recordings, Say Content Is Obscene", San Juan Star, February 3, 1995; Raquel Z. Rivera, "Policing Morality, Mano Dura Style: The Case of Underground Rap and Reggae in Puerto Rico in the Mid-1990s", in Reading Reggaeton.

- ↑ Matt Caputo. "Daddy Yankee: The Voice of His People". Archived from the original on 2008-03-02. Retrieved 2008-01-29.

- ↑ "Amazon.com: Sentimiento: Music: Editorial Reviews". Retrieved 2012-12-03.

- ↑ Giovannetti, Jorge L. (2003). Frances R. Aparicio and Cándida F. Jáquez, ed. "Popular Music and Culture in Puerto Rico: Jamaican and Rap Music as Cross-Cultural Symbols" Musical Migrations: Transnationalism and Cultural Hybridity in the Americas. New York: Palgrave.

- ↑ "Q&A with DJ Blass". 3 July 2014. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ "El Reggaeton". 8 February 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 Raquel Z. Rivera, Wayne Marshall and Deborah Pacini Hernandez. "Reggaeton". Duke University Press. 2009. pg. 143-144

- ↑ "Reggaeton Music News - Lyrics & Noticias de Musica Urbana". Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ Katie Hasty, "T-Pain Soars To No. 1 Ahead Of Rihanna, McCartney", Billboard.com, June 13, 2007.

- 1 2 Artist Chart History – Daddy Yankee – Billboard.com – Accessed November 10, 2008

- ↑ Billboard.com – Artist Chart History – Wisin & Yandel

- ↑ Marshall, "Dem Bow, Dembow, Dembo: Translation and Transnation in Reggaeton." Lied und populäre Kultur / Song and Popular Culture: Jahrbuch des Deutschen Volksliedarchivs 53 (2008): 131-51.

- ↑ Reggaeton. Rivera, Raquel Z., Wayne Marshall, and Deborah Pacini Hernandez, eds. Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2009 and Marshall, Dem Bow, Dembow, Dembo: Translation and Transnation in Reggaeton

- ↑ Marshall, Wayne. "The Rise and Fall of Reggaeton: From Daddy Yankee to Tego Calderón and Beyond" in Jiménez Román, Miriam, and Juan Flores, eds. The Afro-Latin@ reader: history and culture in the United States. Durham NC: Duke University Press, 2010, p. 401.

- ↑ "ICM: Instituto Canario de la Mujer". 17 January 2007. Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ Ben-Yehuda, Ayala (2007-03-31). "Reggaetón Royalty – Ivy Queen Earns Her Crown As A Very Male Subgenre's Only Female Star". Billboard. ISSN 0006-2510. Retrieved 2012-11-29.

- ↑ World, Upside Down. "Reggaeton Nation". Retrieved 10 September 2016.

- ↑ Fairley, Jan (2010). "How To Make Love With Your Clothes On".

- ↑ Andrea Hidalgo (2005-06-02). "Perreo causes Controversy for Reggaeton". Reggaetonline.net.

- 1 2 3 4 Marshall, Wayne. "The Rise of Reggaeton". [Boston Phoenix], 19 January 2006.

- ↑ Reggaeton in Spain