Rancho San Francisco

| Rancho San Francisco | |

|---|---|

|

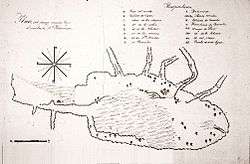

1843 Map of Rancho San Francisco | |

| Location | Northwestern Los Angeles County and eastern Ventura County, California |

| Coordinates | 34°23′24″N 118°34′48″W / 34.390°N 118.580°WCoordinates: 34°23′24″N 118°34′48″W / 34.390°N 118.580°W |

| Area | 48,612 acres (19,673 ha) |

| Official name: Rancho San Francisco[1] | |

| Reference no. | 556 |

| Official name: Oak of the Golden Dream[1] | |

| Reference no. | 168 |

Rancho San Francisco was a land grant in present-day northwestern Los Angeles County and eastern Ventura County, California. It was a grant of 48,612 acres (19,673 ha) by Governor Juan B. Alvarado to Antonio del Valle, a Mexican army officer, in recognition for his service to the state of Alta California.[2][3] It is not related to the city of San Francisco.

The rancho was the location of the first popularly known finding of gold in the Southern California area in 1842, in Placerita Canyon.[4] Much of the present day city of Santa Clarita lies within the boundary of what was Rancho San Francisco. The adobe headquarters of the rancho, and the site of the gold find (known today as the "Oak of the Golden Dream"), are designated California Historical Landmarks.[1] The rancho included portions of the San Gabriel, Santa Susana, Topatopa, and Sierra Pelona Mountain ranges.

Early history

After Mission San Fernando Rey de España was established in 1797, the administrators there realized they would need more land for agriculture and livestock, and they looked north to the Santa Clarita Valley to establish their estancia, or mission rancho. Subsequently, the Tataviam who had been living there were relocated to the Mission, where they were baptized and put to work. The Estancia de San Francisco Xavier was built in 1804 at the confluence of Castaic Creek and the Santa Clara River.[5]

Following the Mexican War of Independence, the missions were secularized and the land taken by the Mexican government. In 1834, Lieutenant Antonio del Valle was assigned to inventory the property of Mission San Fernando. The rancho was supposed to be returned to the Tataviam, but Governor Alvarado deeded it to his friend Del Valle instead on January 22, 1839. The Del Valle family moved into the former estancia buildings (near what is now Castaic).[5]

Del Valle died in 1841. On his deathbed, he attempted to reconcile with his estranged son Ygnacio by writing him a letter and offering the entire rancho to him as his inheritance. Del Valle died before his son received the letter.[2] Ygnacio did return and took possession of the land, but after a lawsuit the property was split with his stepmother.

Los Angeles area gold find

On March 9, 1842, Francisco Lopez, the uncle of Antonio's second wife, Jacoba Feliz, took a rest under an oak tree in Placerita Canyon and had a dream that he was floating on a pool of gold. When he awoke, he pulled a few wild onions from the ground finding flakes of gold in the roots.[6] Contrary to some portraits of him as a farmer who stumbled upon his discovery by dumb luck, Lopez had studied mineralogy at the University of Mexico and had been actively searching for gold.[7] Evidence suggests that gold had previously been found in the area about thirty years prior, but the Lopez gold find was the first popularly documented incident in the area.[8] This sparked a gold rush on a much smaller scale than the 1849 California Gold Rush. About 2,000 people, mostly from the Mexican state of Sonora, came to Rancho San Francisco to mine the gold.[6]

Knowledge of the gold find seems to have remained largely within Mexican territory. John Sutter, who sided with Gov. Manuel Micheltorena during the governor's power struggle with former Gov. Alvarado, was imprisoned after the californio insurrectionists won the Battle of Providencia in 1845. After his release, he headed north through Placerita Canyon, saw the mining operation, and was determined to search for gold near where he later established Sutter's Fort;[6] the latter in Mexican territory.

During the Mexican–American War, Del Valle destroyed the mine to prevent the United States from gaining its control.[9] The tree where Lopez took his nap is now known as the "Oak of the Golden Dream" and is registered as California Historic Landmark #168.[1]

Later history

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo endorsed legitimate land titles held by the ceded land's owners. Jacoba Feliz sued for control of Rancho San Francisco. She prevailed and a judgment was issued in her favor in 1857. Ygnacio Del Valle received the westernmost portion of 13,599 acres (5,503 ha), Feliz (now Salazár) took 21,307 acres (8,623 ha), and her six children received 4,684 acres (1,896 ha) each.[10][11]

Unfortunately, at this time Southern California experienced a great deal of flooding, and ranchers were forced to mortgage their properties in order to sustain their needs during the interruption in producing their food and needs and other damages to the land and buildings. Feliz mortgaged her portion of the land to William Wolfskill, who returned a portion of it back to Del Valle in exchange for him settling her debts. Floods were followed by droughts, which again exacerbated the ranchers' problems.[10] Finally, in 1862 Del Valle was forced to sell off most of his land to oil speculators (the Philadelphia and California Petroleum Company headed by Thomas A. Scott), keeping only his Rancho Camulos.[12] The oilmen were unable to find any oil, and Rancho San Francisco eventually landed in the hands of Henry Newhall, whose name is now closely associated with the Santa Clarita Valley area.[13]

Newhall granted right-of-way to Southern Pacific Railroad to build a rail line to Los Angeles and sold them a portion of the land, upon which sprang a new town that the company named after him, Newhall.[14] Another town grew around the train station and Newhall named it after his hometown, Saugus.

After Newhall's death in 1882, his heirs formed the Newhall Land and Farming Company, which managed the lands. In 1936, Atholl McBean, Newhall's grandson-in-law, found oil on the property and changed the name to Newhall Ranch.[13]

Historic designations

- California Historical Landmark NO. 556 RANCHO SAN FRANCISCO Adobe[1]

- Placerita Canyon State Park – California Historical Landmark NO. 168 OAK OF THE GOLDEN DREAM: where Francisco Lopez found gold.[1]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Los Angeles". California Historical Landmarks. Office of Historic Preservation. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- 1 2 Wormser, Marci (September 1, 1999). "Del Valle descendant pursues her roots". The Signal. Retrieved 2007-04-09.

- ↑ "The Del Valle Family". Rancho Camulos Museum: The Home of Ramona. 2009. Retrieved September 3, 2012.

- ↑ Rawls, James, J. and Richard J. Orsi (eds.) (1999). A golden state: mining and economic development in Gold Rush California. California History Sesquicentennial, 2. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. p. 3. ISBN 0-520-21771-3.

- 1 2 Worden, Leon (August 28, 1996). "Latins Invade, Conquer Western SCV". The Signal. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- 1 2 3 Worden, Leon (October 2005). "California's REAL First Gold". COINage magazine. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- ↑ Worden, Leon (January 24, 1996). "The real story of California's first gold discovery". The Signal. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- ↑ Worden, Leon (August 14, 1996). "New Study Will Nag SCV Historians". The Signal. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- ↑ Rasmussen, Cecilia (November 11, 2001). "Del Valle Family Played a Starring Role in Early California". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 2007-04-09.

- 1 2 "Ygnacio del Valle, Landowner". Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. Retrieved 2007-04-09.

- ↑ "Plat of the Rancho San Francisco finally confirmed to JACOBA FELIZ, et al." 1 AMR 1. Ventura County Recorder Retrieved January 2, 2014 from CountyView GIS (original research).

- ↑ Worden, Leon. "SCV Chronology: A Timeline of Historical Events". Santa Clarita Valley Historical Society. Retrieved March 8, 2011.

- 1 2 Worden, Leon (June 7, 1995). "Prime Valencia Real Estate, $2 an Acre". The Signal. Retrieved 2007-04-20.

- ↑ Newhall, Ruth Waldo (1992). A California Legend: The Newhall Land and Farming Company. Newhall Land and Farming Company.

See also

External links