Railway signalling

Railway signalling is a system used to direct railway traffic and keep trains clear of each other at all times. Trains move on fixed rails, making them uniquely susceptible to collision. This susceptibility is exacerbated by the enormous weight and inertia of a train, which make it difficult to quickly stop when encountering an obstacle. In the UK, the Regulation of Railways Act 1889 introduced a series of requirements on matters such as the implementation of interlocked block signalling and other safety measures as a direct result of the Armagh rail disaster in that year.

Most forms of train control involve movement authority being passed from those responsible for each section of a rail network (e.g., a signalman or stationmaster) to the train crew. The set of rules and the physical equipment used to accomplish this determine what is known as the method of working (UK), method of operation (US) or safeworking (Aus.). Not all these methods require the use of physical signals, and some systems are specific to single track railways.

The earliest rail cars were first hauled by horses or mules. A mounted flagman on a horse preceded some early trains. Hand and arm signals were used to direct the “train drivers”. Foggy and poor-visibility conditions gave rise to flags and lanterns. Wayside signalling dates back as far as 1832, and used elevated flags or balls that could be seen from afar.

Timetable operation

The simplest form of operation, at least in terms of equipment, is to run the system according to a timetable. Every train crew understands and adheres to a fixed schedule. Trains may only run on each track section at a scheduled time, during which they have 'possession' and no other train may use the same section.

When trains run in opposite directions on a single-track railroad, meeting points ("meets") are scheduled, at which each train must wait for the other at a passing place. Neither train is permitted to move before the other has arrived. In the US the display of two green flags (green lights at night) is an indication that another train is following the first and the waiting train must wait for the next train to pass. In addition, the train carrying the flags gives eight blasts on the whistle as it approaches. The waiting train must return eight blasts before the flag carrying train may proceed.

The timetable system has several disadvantages. First, there is no positive confirmation that the track ahead is clear, only that it is scheduled to be clear. The system does not allow for engine failures and other such problems, but the timetable is set up so that there should be sufficient time between trains for the crew of a failed or delayed train to walk far enough to set warning flags, flares, and detonators or torpedoes (UK and US terminology, respectively) to alert any other train crew.

A second problem is the system's inflexibility. Trains cannot be added, delayed, or rescheduled without advance notice.

A third problem is a corollary of the second: the system is inefficient. To provide flexibility, the timetable must give trains a broad allocation of time to allow for delays, so the line is not in the possession of each train for longer than is otherwise necessary.

Nonetheless, this system permits operation on a vast scale, with no requirements for any kind of communication that travels faster than a train. Timetable operation was the normal mode of operation in North America in the early days of the railroad.

Timetable and train order

With the advent of the telegraph in 1851, a more sophisticated system became possible because this provided a means whereby messages could be transmitted ahead of the trains. The telegraph allows the dissemination of any timetable changes, known as train orders. These allow the cancellation, rescheduling and addition of train services.

North American practice meant that train crews generally received their orders at the next station at which they stopped, or were sometimes handed up to a locomotive 'on the run' via a long staff. Train orders allowed dispatchers to set up meets at sidings, force a train to wait in a siding for a priority train to pass, and to maintain at least one block spacing between trains going the same direction.

Timetable and train order operation was commonly used on American railroads until the 1960s, including some quite large operations such as the Wabash Railroad and the Nickel Plate Road. Train order traffic control was used in Canada until the late 1980s on the Algoma Central Railway and some spurs of the Canadian Pacific Railway.

Timetable and train order was not used widely outside North America, and has been phased out in favor of radio dispatch on many light-traffic lines and electronic signals on high-traffic lines. More details of North American operating methods is given below.

A similar method, known as 'Telegraph and Crossing Order' was used on some busy single lines in the UK during the 19th century. However, a series of head-on collisions resulted from authority to proceed being wrongly given or misunderstood by the train crew - the worst of which was the collision between Norwich and Brundall, Norfolk, in 1874. As a result, the system was phased out in favour of token systems. This eliminated the danger of ambiguous or conflicting instructions being given because token systems rely on objects to give authority, rather than verbal or written instructions; whereas it is very difficult to completely prevent conflicting orders being given, it is relatively simple to prevent conflicting tokens being handed out.

Block signalling

Trains cannot collide with each other if they are not permitted to occupy the same section of track at the same time, so railway lines are divided into sections known as blocks. In normal circumstances, only one train is permitted in each block at a time. This principle forms the basis of most railway safety systems.

History of block signalling

On double tracked railway lines, which enabled trains to travel in one direction on each track, it was necessary to space trains far enough apart to ensure that they could not collide. In the very early days of railways, men (originally called 'policemen', and is the origin of UK signalmen being referred to as "bob", "bobby" or "officer", when train-crew are speaking to them via a signal telephone) were employed to stand at intervals ("blocks") along the line with a stopwatch and use hand signals to inform train drivers that a train had passed more or less than a certain number of minutes previously. This was called "time interval working". If a train had passed very recently, the following train was expected to slow down to allow more space to develop.

The watchmen had no way of knowing whether a train had cleared the line ahead, so if a preceding train stopped for any reason, the crew of a following train would have no way of knowing unless it was clearly visible. As a result, accidents were common in the early days of railways. With the invention of the electrical telegraph, it became possible for staff at a station or signal box to send a message (usually a specific number of rings on a bell) to confirm that a train had passed and that a specific block was clear. This was called the "absolute block system".

Fixed mechanical signals began to replace hand signals from the 1830s. These were originally worked locally, but it later became normal practice to operate all the signals on a particular block with levers grouped together in a signal box. When a train passed into a block, a signalman would protect that block by setting its signal to 'danger'. When an 'all clear' message was received, the signalman would move the signal into the 'clear' position.

The absolute block system came into use gradually during the 1850s and 1860s and became mandatory in the United Kingdom after Parliament passed legislation in 1889 following a number of accidents, most notably the Armagh rail disaster. This required block signalling for all passenger railways, together with interlocking, both of which form the basis of modern signalling practice today. Similar legislation was passed by the United States around the same time.

Not all blocks are controlled using fixed signals. On some single track railways in the UK, particularly those with low usage, it is common to use token systems that rely on the train driver's physical possession of a unique token as authority to occupy the line, normally in addition to fixed signals.

Entering and leaving a manually controlled block

Before allowing a train to enter a block, a signalman must be certain that it is not already occupied. When a train leaves a block, he must inform the signalman controlling entry to the block. Even if the signalman receives advice that the previous train has left a block, he is usually required to seek permission from the next signal box to admit the next train. When a train arrives at the end of a block section, before the signalman sends the message that the train has arrived, he must be able to see the end-of-train marker on the back of the last vehicle. This ensures that no part of the train has become detached and remains within the section. The end of train marker might be a coloured disc (usually red) by day or a coloured oil or electric lamp (again, usually red). If a train enters the next block before the signalman sees that the disc or lamp is missing, he asks the next signal box to stop the train and investigate.

Permissive and absolute blocks

Under a permissive block system, trains are permitted to pass signals indicating the line ahead is occupied, but only at such a speed that they can stop safely driving by sight. This allows improved efficiency in some situations and is mostly used in the USA, and in most countries is restricted to freight trains only, and may be restricted depending on the level of visibility.

Permissive block working may also be used in an emergency, either when a driver is unable to contact a signalman after being held at a danger signal for a specific time, although this is only permitted when the signal does not protect any conflicting moves, and also when the signalman is unable to contact the next signal box to make sure the previous train has passed, for example if the telegraph wires are down. In these cases, trains must proceed at very low speed (typically 20 mph (32 km/h) or less) so that they are able to stop short of any obstruction. In most cases this is not allowed during times of poor visibility (e.g., fog or falling snow).

Even with an absolute block system, multiple trains may enter a block with authorization. This may be necessary, e.g., in order to split or join trains together, or to rescue failed trains. In giving authorization, the signalman also ensures that the driver knows precisely what to expect ahead. The driver must operate the train in a safe manner taking this information into account. Generally, the signal remains at danger, and the driver is given verbal authority, usually by a yellow flag, to pass a signal at danger, and the presence of the train in front is explained. Where trains regularly enter occupied blocks, such as stations where coupling takes place, a subsidiary signal, sometimes known as a "calling on" signal, is provided for these movements, otherwise they are accomplished through train orders.

Automatic block

Under automatic block signalling, signals indicate whether or not a train may enter a block based on automatic train detection indicating whether a block is clear. The signals may also be controlled by a signalman, so that they only provide a proceed indication if the signalman sets the signal accordingly and the block is clear.

Fixed block

Most blocks are "fixed", i.e. they include the section of track between two fixed points. On timetable, train order, and token-based systems, blocks usually start and end at selected stations. On signalling-based systems, blocks start and end at signals.

The lengths of blocks are designed to allow trains to operate as frequently as necessary. A lightly used line might have blocks many kilometres long, but a busy commuter line might have blocks a few hundred metres long.

A train is not permitted to enter a block until a signal indicates that the train may proceed, a dispatcher or signalman instructs the driver accordingly, or the driver takes possession of the appropriate token. In most cases, a train cannot enter the block until not only the block itself is clear of trains, but there is also an empty section beyond the end of the block for at least the distance required to stop the train. In signalling-based systems with closely spaced signals, this overlap could be as far as the signal following the one at the end of the section, effectively enforcing a space between trains of two blocks.

When calculating the size of the blocks, and therefore the spacing between the signals, the following have to be taken into account:

- Line speed (the maximum permitted speed over the line-section)

- Train speed (the maximum speed of different types of traffic)

- Gradient (to compensate for longer or shorter braking distances)

- The braking characteristics of trains (different types of train, e.g., freight, High-Speed passenger, have different inertial figures)

- Sighting (how far ahead a driver can see a signal)

- Reaction time (of the driver)

Historically, some lines operated so that certain large or high speed trains were signalled under different rules and only given the right of way if two blocks in front of the train were clear.

Moving block

One disadvantage of having fixed blocks is that the faster trains are allowed to run, the longer the stopping distance, and therefore the longer the blocks need to be, thus decreasing the line's capacity.

Under a moving block system, computers calculate a 'safe zone' around each moving train that no other train is allowed to enter. The system depends on knowledge of the precise location and speed and direction of each train, which is determined by a combination of several sensors: active and passive markers along the track and trainborne tachometers and speedometers (GPS systems cannot be used because they do not work in tunnels.) With a moving block, lineside signals are unnecessary, and instructions are passed directly to the trains. This has the advantage of increasing track capacity by allowing trains to run closer together while maintaining the required safety margins.

Moving block is in use on Vancouver's Skytrain, London's Docklands Light Railway, New York City's BMT Canarsie Line, and London Underground's Jubilee, Victoria and Northern lines. It was supposed to be the enabling technology on the modernisation of Britain's West Coast Main Line that would let trains run at a higher maximum speed (140 mph or 230 km/h)—but the technology was deemed not mature enough, considering the variety of traffic, such as freight and local trains as well as expresses, to be accommodated on the line and the plan was dropped.[1][2] It forms part of the European Rail Traffic Management System's level-3 specification for future installation in the European Train Control System, which (at level 3) features moving blocks that let trains follow each other at exact braking distances.

Centralized traffic control

Centralized traffic control (CTC) is a form of railway signalling that originated in North America. CTC consolidates train routing decisions that were previously carried out by local signal operators or the train crews themselves. The system consists of a centralized train dispatcher's office that controls railroad interlockings and traffic flows in portions of the rail system designated as CTC territory.

Train detection

Track circuits

One of the most common ways to determine whether a section of line is occupied is by use of a track circuit. The rails at either end of each section are electrically isolated from the next section, and an electrical current is fed to both running rails at one end. A relay at the other end is connected to both rails. When the section is unoccupied, the relay coil completes an electrical circuit, and is energized. However, when a train enters the section, it short-circuits the current in the rails, and the relay is de-energized. This method does not explicitly need to check that the entire train has left the section. If part of the train remains in the section, the track circuit detects that part.

This type of circuit detects the absence of trains, both for setting the signal indication and for providing various interlocking functions—for example, not permitting points to move when a train stands over them. Electrical circuits also prove that points are in the appropriate position before a signal over them may be cleared. Modern UK trains, and staff working in track circuit block areas, carry Track Circuit Clips (TCC) so that, in the event of something fouling an adjacent running-line, the track circuit can be short-circuited. This places signals on that track to 'danger' and can be used to help prevent a collision before the signalman can be alerted.

Axle counters

An alternate method of determining the occupied status of a block uses devices located at its beginning and end that count the number of axles that enter and leave the block section. If the number of axles leaving the block section equals those that entered it, the block is assumed to be clear. Axle counters provide similar functions to track circuits, but also exhibit a few other characteristics. In a damp environment an axle counted section can be far longer than a track circuited one. The low ballast resistance of very long track circuits reduces their sensitivity. Track circuits can automatically detect some types of track defect such as a broken rail. In the event of power restoration after a power failure, an axle counted section is left in an undetermined state until a train has passed through the affected section. When a block section has been left in an undetermined state, it may be worked under pilot working. The first train to pass through the section would typically do so at a speed no greater than 20 mph (32 km/h) or walking pace in areas of high transition, reverse curvature and may have someone who has a good local knowledge of the area acting as the pilotman. A track circuited section immediately detects the presence of a train in section.

Fixed signals

On most railways, physical signals are erected at the lineside to indicate to drivers whether the line ahead is occupied and to ensure that sufficient space exists between trains to allow them to stop.

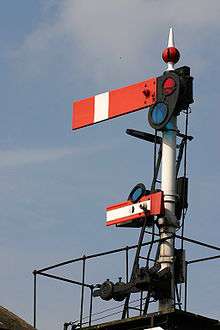

Mechanical signals

Older forms of signal displayed their different aspects by their physical position. The earliest types comprised a board that was either turned face-on and fully visible to the driver, or rotated so as to be practically invisible. While this type of signal is still in use in some countries (e.g., France and Germany), by far the most common form of mechanical signal worldwide is the semaphore signal. This comprises a pivoted arm or blade that can be inclined at different angles. A horizontal arm is the most restrictive indication (for 'danger', 'caution', 'stop and proceed' or 'stop and stay' depending on the type of signal).

To enable trains to run at night, one or more lights are usually provided at each signal. Typically this comprises a permanently lit oil lamp with movable coloured spectacles in front that alter the colour of the light. The driver therefore had to learn one set of indications for daytime viewing and another for nighttime viewing.

Whilst it is normal to associate the presentation of a green light with a safe condition, this was not historically the case. In the very early days of railway signalling, the first coloured lights (associated with the turned signals above) presented a white light for 'clear' and a red light for 'danger'. Green was originally used to indicate 'caution' but fell out of use when the time interval system was discontinued. A green light subsequently replaced white for 'clear', to address concerns that a broken red lens could be taken by a driver as a false 'clear' indication. It was not until scientists at Corning Glassworks perfected a shade of yellow without any tinges of green or red that yellow became the accepted colour for 'caution'.

Mechanical signals are usually remotely operated by wire from a lever in a signal box, but electrical or hydraulic operation is normally used for signals that are located too distant for manual operation.

Colour lights signals

On most modern railways, colour light signals have largely replaced mechanical ones. Colour light signals have the advantage of displaying the same aspects by night as by day, and require less maintenance than mechanical signals.

Although signals vary widely between countries, and even between railways within a given country, a typical system of aspects would be:

- Green: Proceed at line speed. Expect to find next signal displaying green or yellow.

- Yellow: Prepare to find next signal displaying red.

- Red: Stop.

On some railways, colour light signals display the same set of aspects as shown by the lights on mechanical signals during darkness.

Route signalling and speed signalling

Signalling of British origin generally conforms to the principle of route signalling. Most railway systems around the world, however, use what is known as speed signalling.

Under route signalling, a driver is informed which route the train will take beyond each signal (unless only one route is possible). This is achieved by a route indicator attached to the signal. The driver uses his route knowledge, reinforced by speed restriction signs fixed at the lineside, to drive the train at the correct speed for the route to be taken. This method has the disadvantage that the driver may be unfamiliar with a route onto which he has been diverted due to some emergency condition. Several accidents have been caused by this alone.[3] For this reason, in the UK drivers are only allowed to drive on routes that they have been trained on and must regularly travel over the lesser used diversionary routes to keep their route knowledge up to date.

Under speed signalling, the signal aspect informs the driver at what speed he may proceed, but not necessarily the route the train will take. Speed signalling requires a far greater range of signal aspects than route signalling, but less dependence is placed on drivers' route knowledge.

Approach release

When the train is routed towards a diverging route that must be taken at a speed significantly less than the mainline speed, the driver must be given adequate prior warning.

Under 'route signalling', the aspects necessary to control speed do not exist, so a system known as approach release is employed. This involves holding the junction signal at a restrictive aspect (typically 'stop') so that the signals on the approach show the correct sequence of caution aspects. The driver brakes in accordance with the caution aspect, without necessarily being aware that the diverging route has in fact been set. As the train approaches the junction signal, its aspect may clear to whatever aspect the current track occupancy ahead permits. Where the turnout speed is the same, or nearly the same, as the mainline speed, approach release is unnecessary.

Under speed signalling, the signals approaching the divergence display aspects appropriate to control the trains speed, so no 'approach release' is required.

Safety systems

A train driver failing to respond to a signal's indication can be disastrous. As a result, various auxiliary safety systems have been devised. Any such system requires installation of some degree of trainborne equipment. Some systems only intervene in the event of a signal being passed at danger (SPAD). Others include audible and/or visual indications inside the driver's cab to supplement the lineside signals. Automatic brake application occurs if the driver should fail to acknowledge a warning. Some systems act intermittently (at each signal), but the most sophisticated systems provide continuous supervision.

In-cab safety systems are of great benefit during fog, when poor visibility would otherwise require that restrictive measures be put in place.

Cab signalling

Cab signalling is a system that communicates signalling information into the train cab (driving position). The simplest systems 'repeat' the trackside signal aspect, while more sophisticated systems also display the maximum permitted speed and dynamic information for the route ahead, based on the distance in front which is clear and the braking characteristics of the train. In modern systems, a train protection system is usually overlaid on top of the cab signalling system and will automatically apply the brakes and bring the train to a stand if the driver fails to control the speed of the train in accordance with the system demands.[4] Cab signalling systems range from simple coded track circuits, to transponders that communicate with the cab, and communication-based train control systems.

Interlocking

In the early days of the railways, signalmen were responsible for ensuring any points (US: switches) were set correctly before allowing a train to proceed. Mistakes, however, led to accidents, sometimes with fatalities. The concept of the interlocking of points, signals and other appliances was introduced to improve safety. This prevents a signalman from operating appliances in an unsafe sequence, such as setting a signal to 'clear' while one or more sets of points in the route ahead of the signal are improperly set.[3]

Early interlocking systems used mechanical devices both to operate the signalling appliances and to ensure their safe operation. Beginning around the 1930s, electrical relay interlockings were used. Since the late 1980s, new interlocking systems have tended to be of the electronic variety.

Operating rules

Operating rules, policies and procedures are used by railroads to enhance safety. Specific operating rules may differ from country to country and even from railroad to railroad within the same country.

Argentinian operating rules

In Argentina, operating rules are described in the Reglamento interno técnico de operaciones [R.I.T.O.] (technical operating rule-book).

Australian operating rules

In Australia, the application of operating rules is called Safeworking. The method of working for any particular region or location is referred-to as the 'Safeworking system' for that region. Operating rules differ from state to state, although attempts are being made to formulate a national standard.

North American operating rules

In North America and especially the US, operating rules are called method of operation. There are five main sets of operating rules in North America:

- Canadian Rail Operating Rules (CROR), used by most Canadian railways

- General Code of Operating Rules (GCOR), used by many Class I railroads, Class II railroads, and many Short-line railroads

- Northeast Operating Rules Advisory Committee (NORAC), used by many railroads in the Northeast US

- Class I Norfolk Southern uses a unique set of operating rules.

- Class I CSX Transportation uses a unique set of operating rules.

UK operating rules

For the UK, the operating rulebook is called "GE/RT8000 Rule Book[5]" or more commonly known as the "Rule Book" by railway employees. It is controlled by the Rail Safety and Standards Board (RSSB), which is independent from Network Rail or any other Train/Freight Operating Company. Most heritage railways operate to a simplified variant of a British Railways rule book.

Italian operating rules

In Italy, railway signalling is described in a particular instruction called Regolamento Segnali (Signal Regulation).

Indian operating rules

In Indian Railways operating rules are called 'The General Rules'. The General Rules are common for all zonal railways of Indian Railway and can be amended only by the Railway Board. Subsidiary rules are added to the General Rules by zonal railways, which does not infringe the general rule. Corrections are brought about from time to time through correction slips.

See also

References

- ↑ Meek, James (1 April 2004). "Special investigation: incompetence at Railtrack". The Guardian. p. 2. Retrieved 16 January 2012.

- ↑ The Modernisation of the West Coast Main Line. National Audit Office. p. 26. OCLC 76874805.

- 1 2 Rolt, L. T. C (1966). Red for Danger. Newton Abott, Devon, United Kingdom: David & Charles Ltd.

- ↑ Elements of Railway Signaling, General Railway Signal (June 1979)

- ↑ "The Rule Book".

- Brian, Frank W. (May 1, 2006). "Railroad's Traffic Control Systems". Trains. Kalmbach Publishing Co. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved August 16, 2006.

- Colburn, Robert (October 14, 2013). "A History of Railroad Signals". The Institute. Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers. Tech Focus. Archived from the original on October 22, 2013. Retrieved October 22, 2013.

- General Code of Operating Rules (5th ed.). BNSF Railway Company. 2005.

External links

- The Signal Page (TSP) – railway signalling world wide (Dutch), (English)

- RailServe.com Signals & Communications

- Railways: History, Signalling, Engineering and

- Signalling Record Society

- The Institution of Railway Signal Engineers