Radiative forcing

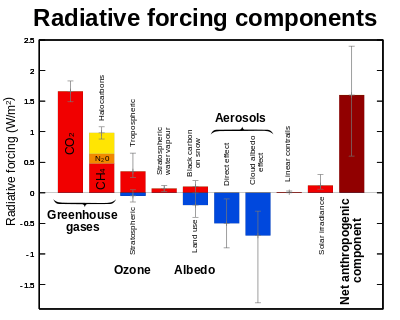

Radiative forcing or climate forcing is defined as the difference of insolation (sunlight) absorbed by the Earth and energy radiated back to space.[1] Typically, radiative forcing is quantified at the tropopause in units of watts per square meter of the Earth's surface. A positive forcing (more incoming energy) warms the system, while negative forcing (more outgoing energy) cools it. Causes of radiative forcing include changes in insolation and the concentrations of radiatively active gases, commonly known as greenhouse gases and aerosols.

Radiation balance

Almost all of the energy that affects Earth's climate is received as radiant energy from the Sun. The planet and its atmosphere absorb and reflect some of the energy, while long-wave energy is radiated back into space. The balance between absorbed and radiated energy determines the average global temperature. Because the atmosphere absorbs some of the re-radiated long-wave energy, the planet is warmer than it would be in the absence of the atmosphere: see greenhouse effect.

The radiation balance is altered by such factors as the intensity of solar energy, reflectivity of clouds or gases, absorption by various greenhouse gases or surfaces and heat emission by various materials. Any such alteration is a radiative forcing, and changes the balance. This happens continuously as sunlight hits the surface, clouds and aerosols form, the concentrations of atmospheric gases vary and seasons alter the ground cover.

IPCC usage

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) AR4 report defines radiative forcings as:[3]

"Radiative forcing is a measure of the influence a factor has in altering the balance of incoming and outgoing energy in the Earth-atmosphere system and is an index of the importance of the factor as a potential climate change mechanism. In this report radiative forcing values are for changes relative to preindustrial conditions defined at 1750 and are expressed in Watts per square meter (W/m2)."

In simple terms, radiative forcing is "...the rate of energy change per unit area of the globe as measured at the top of the atmosphere."[4] In the context of climate change, the term "forcing" is restricted to changes in the radiation balance of the surface-troposphere system imposed by external factors, with no changes in stratospheric dynamics, no surface and tropospheric feedbacks in operation (i.e., no secondary effects induced because of changes in tropospheric motions or its thermodynamic state), and no dynamically induced changes in the amount and distribution of atmospheric water (vapour, liquid, and solid forms).

Climate sensitivity

Radiative forcing can be used to estimate a subsequent change in equilibrium surface temperature (ΔTs) arising from that forcing via the equation:

where λ is the climate sensitivity, usually with units in K/(W/m2), and ΔF is the radiative forcing.[5] A typical value of λ is 0.8 K/(W/m2), which gives a warming of 3K for doubling of CO2.

Example calculations

Solar forcing

Radiative forcing (measured in Watts per square meter) can be estimated in different ways for different components. For solar irradiance (i.e., "solar forcing"), the radiative forcing is simply the change in the average amount of solar energy absorbed per square meter of the Earth's area. Since the Earth's cross-sectional area exposed to the Sun (πr2) is equal to 1/4 of the surface area of the Earth (4πr2), the solar input per unit area is one quarter the change in solar intensity. This must be multiplied by the fraction of incident sunlight that is absorbed, F=(1-R), where R is the reflectivity (albedo), of the Earth. The albedo is approximately 0.3, so F is approximately equal to 0.7. Thus, the solar forcing is the change in the solar intensity divided by 4 and multiplied by 0.7.

Likewise, a change in albedo will produce a solar forcing equal to the change in albedo divided by 4 multiplied by the solar constant.

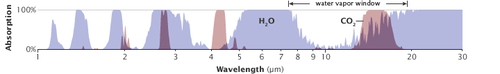

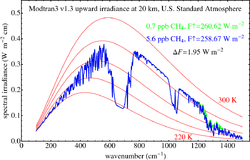

Forcing due to atmospheric gas

For a greenhouse gas, such as carbon dioxide, radiative transfer codes that examine each spectral line for atmospheric conditions can be used to calculate the change ΔF as a function of changing concentration. These calculations can often be simplified into an algebraic formulation that is specific to that gas.

For instance, the simplified first-order approximation expression for carbon dioxide is:

where C is the CO2 concentration in parts per million by volume and C0 is the reference concentration.[6] The relationship between carbon dioxide and radiative forcing is logarithmic[7] and thus increased concentrations have a progressively smaller warming effect.

A different formula applies for other greenhouse gases such as methane and N2O (square-root dependence) or CFCs (linear), with coefficients that can be found e.g. in the IPCC reports.[8]

Related measures

Radiative forcing is a useful way to compare different causes of perturbations in a climate system. Other possible tools can be constructed for the same purpose: for example Shine et al.[9] say "...recent experiments indicate that for changes in absorbing aerosols and ozone, the predictive ability of radiative forcing is much worse... we propose an alternative, the 'adjusted troposphere and stratosphere forcing'. We present GCM calculations showing that it is a significantly more reliable predictor of this GCM's surface temperature change than radiative forcing. It is a candidate to supplement radiative forcing as a metric for comparing different mechanisms...". In this quote, GCM stands for "global circulation model", and the word "predictive" does not refer to the ability of GCMs to forecast climate change. Instead, it refers to the ability of the alternative tool proposed by the authors to help explain the system response.

History

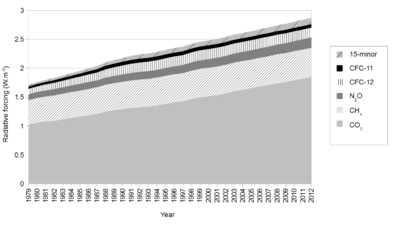

The table below (derived from atmospheric radiative transfer models) shows changes in radiative forcing between 1979 and 2013.[10] The table includes the contribution to radiative forcing from carbon dioxide (CO2), methane (CH

4), nitrous oxide (N

2O); chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) 12 and 11; and fifteen other minor, long-lived, halogenated gases.[11] The table includes the contribution to radiative forcing of long-lived greenhouse gases. It does not include other forcings, such as aerosols and changes in solar activity.

| Year | CO2 | CH 4 | N 2O | CFC-12 | CFC-11 | 15-minor | Total | CO2-eq ppm | AGGI 1990 = 1 | AGGI % change |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1979 | 1.027 | 0.419 | 0.104 | 0.092 | 0.039 | 0.031 | 1.712 | 383 | 0.786 | |

| 1980 | 1.058 | 0.426 | 0.104 | 0.097 | 0.042 | 0.034 | 1.761 | 386 | 0.808 | 2.8 |

| 1981 | 1.077 | 0.433 | 0.107 | 0.102 | 0.044 | 0.036 | 1.799 | 389 | 0.826 | 2.2 |

| 1982 | 1.089 | 0.440 | 0.111 | 0.108 | 0.046 | 0.038 | 1.831 | 391 | 0.841 | 1.8 |

| 1983 | 1.115 | 0.443 | 0.113 | 0.113 | 0.048 | 0.041 | 1.873 | 395 | 0.860 | 2.2 |

| 1984 | 1.140 | 0.446 | 0.116 | 0.118 | 0.050 | 0.044 | 1.913 | 397 | 0.878 | 2.2 |

| 1985 | 1.162 | 0.451 | 0.118 | 0.123 | 0.053 | 0.047 | 1.953 | 401 | 0.897 | 2.1 |

| 1986 | 1.184 | 0.456 | 0.122 | 0.129 | 0.056 | 0.049 | 1.996 | 404 | 0.916 | 2.2 |

| 1987 | 1.211 | 0.460 | 0.120 | 0.135 | 0.059 | 0.053 | 2.039 | 407 | 0.936 | 2.2 |

| 1988 | 1.250 | 0.464 | 0.123 | 0.143 | 0.062 | 0.057 | 2.099 | 412 | 0.964 | 3.0 |

| 1989 | 1.274 | 0.468 | 0.126 | 0.149 | 0.064 | 0.061 | 2.144 | 415 | 0.984 | 2.1 |

| 1990 | 1.293 | 0.472 | 0.129 | 0.154 | 0.065 | 0.065 | 2.178 | 418 | 1.000 | 1.6 |

| 1991 | 1.313 | 0.476 | 0.131 | 0.158 | 0.067 | 0.069 | 2.213 | 420 | 1.016 | 1.6 |

| 1992 | 1.324 | 0.480 | 0.133 | 0.162 | 0.067 | 0.072 | 2.238 | 422 | 1.027 | 1.1 |

| 1993 | 1.334 | 0.481 | 0.134 | 0.164 | 0.068 | 0.074 | 2.254 | 424 | 1.035 | 0.7 |

| 1994 | 1.356 | 0.483 | 0.134 | 0.166 | 0.068 | 0.075 | 2.282 | 426 | 1.048 | 1.3 |

| 1995 | 1.383 | 0.485 | 0.136 | 0.168 | 0.067 | 0.077 | 2.317 | 429 | 1.064 | 1.5 |

| 1996 | 1.410 | 0.486 | 0.139 | 0.169 | 0.067 | 0.078 | 2.350 | 431 | 1.079 | 1.4 |

| 1997 | 1.426 | 0.487 | 0.142 | 0.171 | 0.067 | 0.079 | 2.372 | 433 | 1.089 | 0.9 |

| 1998 | 1.465 | 0.491 | 0.145 | 0.172 | 0.067 | 0.080 | 2.419 | 437 | 1.111 | 2.0 |

| 1999 | 1.495 | 0.494 | 0.148 | 0.173 | 0.066 | 0.082 | 2.458 | 440 | 1.128 | 1.6 |

| 2000 | 1.513 | 0.494 | 0.151 | 0.173 | 0.066 | 0.083 | 2.481 | 442 | 1.139 | 0.9 |

| 2001 | 1.535 | 0.494 | 0.153 | 0.174 | 0.065 | 0.085 | 2.506 | 444 | 1.150 | 1.0 |

| 2002 | 1.564 | 0.494 | 0.156 | 0.174 | 0.065 | 0.087 | 2.539 | 447 | 1.166 | 1.3 |

| 2003 | 1.601 | 0.496 | 0.158 | 0.174 | 0.064 | 0.088 | 2.580 | 450 | 1.185 | 1.6 |

| 2004 | 1.627 | 0.496 | 0.160 | 0.174 | 0.063 | 0.090 | 2.610 | 453 | 1.198 | 1.1 |

| 2005 | 1.655 | 0.495 | 0.162 | 0.173 | 0.063 | 0.092 | 2.640 | 455 | 1.212 | 1.2 |

| 2006 | 1.685 | 0.495 | 0.165 | 0.173 | 0.062 | 0.095 | 2.675 | 458 | 1.228 | 1.3 |

| 2007 | 1.710 | 0.498 | 0.167 | 0.172 | 0.062 | 0.097 | 2.706 | 461 | 1.242 | 1.1 |

| 2008 | 1.739 | 0.500 | 0.170 | 0.171 | 0.061 | 0.100 | 2.742 | 464 | 1.259 | 1.3 |

| 2009 | 1.760 | 0.502 | 0.172 | 0.171 | 0.061 | 0.103 | 2.768 | 466 | 1.271 | 1.0 |

| 2010 | 1.791 | 0.504 | 0.174 | 0.170 | 0.060 | 0.106 | 2.805 | 470 | 1.288 | 1.3 |

| 2011 | 1.818 | 0.505 | 0.178 | 0.169 | 0.060 | 0.109 | 2.838 | 473 | 1.303 | 1.2 |

| 2012 | 1.846 | 0.507 | 0.181 | 0.168 | 0.059 | 0.111 | 2.873 | 476 | 1.319 | 1.2 |

| 2013 | 1.884 | 0.509 | 0.184 | 0.167 | 0.059 | 0.114 | 2.916 | 479 | 1.338 | 1.5 |

| 2014 | 1.909 | 0.500 | 0.187 | 0.166 | 0.058 | 0.116 | 2.936 | 481 | 1.356 | 1.6 |

The table shows that CO2 dominates the total forcing, with methane and chlorofluorocarbons (CFC) becoming relatively smaller contributors to the total forcing over time.[10] The five major greenhouse gases account for about 96% of the direct radiative forcing by long-lived greenhouse gas increases since 1750. The remaining 4% is contributed by the 15 minor halogenated gases.

The table also includes an "Annual Greenhouse Gas Index" (AGGI), which is defined as the ratio of the total direct radiative forcing due to long-lived greenhouse gases for any year for which adequate global measurements exist to that which was present in 1990.[10] 1990 was chosen because it is the baseline year for the Kyoto Protocol. This index is a measure of the inter-annual changes in conditions that affect carbon dioxide emission and uptake, methane and nitrous oxide sources and sinks, the decline in the atmospheric abundance of ozone-depleting chemicals related to the Montreal Protocol. and the increase in their substitutes (hydrogenated CFCs (HCFCs) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFC). Most of this increase is related to CO2. For 2013, the AGGI was 1.34 (representing an increase in total direct radiative forcing of 34% since 1990). The increase in CO2 forcing alone since 1990 was about 46%. The decline in CFCs considerably tempered the increase in net radiative forcing.

See also

References

- ↑ Shindell, Drew (2013). "Radiative Forcing in the AR5" (PDF). Retrieved 15 September 2016.

- ↑ "NASA: Climate Forcings and Global Warming". January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Climate Change 2007: Synthesis Report

- ↑ Rockström, Johan; Steffen, Will; Noone, Kevin; Persson, Asa; Chapin, F. Stuart; Lambin, Eric F.; Lenton, Timothy F.; Scheffer, M; et al. (2009). "A safe operating space for humanity". Nature. 461 (7263): 472–475. Bibcode:2009Natur.461..472R. doi:10.1038/461472a. PMID 19779433.

- ↑ "IPCC Third Assessment Report - Climate Change 2001". grida.no.

- ↑ Myhre et al., New estimates of radiative forcing due to well mixed greenhouse gases, Geophysical Research Letters, Vol 25, No. 14, pp 2715–2718, 1998

- ↑ Huang, Y., and M. Bani Shahabadi (2014) Why logarithmic?, J. Geophys. Res. Atmos., 119, 13,683–13,689

- ↑ IPCC WG-1 report

- ↑ Shine et al., An alternative to radiative forcing for estimating the relative importance of climate change mechanisms, Geophysical Research Letters, Vol 30, No. 20, 2047, doi:10.1029/2003GL018141, 2003

- 1 2 3 4

This article incorporates public domain material from the NOAA document: Butler, J.H. and S.A. Montzka (1 August 2013). "THE NOAA ANNUAL GREENHOUSE GAS INDEX (AGGI)". NOAA/ESRL Global Monitoring Division

This article incorporates public domain material from the NOAA document: Butler, J.H. and S.A. Montzka (1 August 2013). "THE NOAA ANNUAL GREENHOUSE GAS INDEX (AGGI)". NOAA/ESRL Global Monitoring Division

- ↑ CFC-113, tetrachloromethane (CCl

4), trichloromethane (CH

3CCl

3); hydrochlorofluorocarbons (HCFCs) 22, 141b and 142b; hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) 134a, 152a, 23, 143a, and 125; sulfur hexafluoride (SF

6), and halons 1211, 1301 and 2402)

External links

- IPCC glossary

- CO2: The Thermostat that Controls Earth's Temperature by NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, October, 2010, Forcing vs. Feedbacks

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s Fourth Assessment Report (2007), Chapter 2, "Changes in Atmospheric Constituents and Radiative Forcing," pp. 133–134 (PDF, 8.6 MB, 106 pp.).

- U.S. EPA (2009), Climate Change – Science. Explanation of climate change topics including radiative forcing.

- United States National Research Council (2005), Radiative Forcing of Climate Change: Expanding the Concept and Addressing Uncertainties, Board on Atmospheric Sciences and Climate

- Small volcanoes add up to cooler climate; Airborne particles help explain why temperatures rose less last decade August 13, 2011; Vol.180 #4 (p. 5) Science News

- NASA: The Atmosphere’s Energy Budget

- Energy balance: the simplest climate model

- Explore Mann's climate projections from Scientific American