Hyperbolic trajectory

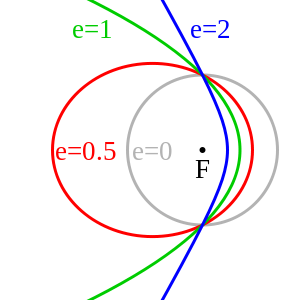

In astrodynamics or celestial mechanics, a hyperbolic trajectory is the trajectory of any object around a central body with more than enough speed to escape the central object's gravitational pull. The name derives from the fact that according to Newtonian theory such an orbit has the shape of a hyperbola. In more technical terms this can be expressed by the condition that the orbital eccentricity is greater than one.

Under standard assumptions a body traveling along this trajectory will coast to infinity, arriving there with hyperbolic excess velocity relative to the central body. Similarly to parabolic trajectory all hyperbolic trajectories are also escape trajectories. The specific energy of a hyperbolic trajectory orbit is positive.

Planetary flybys, used for gravitational slingshots, can be described within the planet's sphere of influence using hyperbolic trajectories.

Hyperbolic excess velocity

Under standard assumptions the body traveling along a hyperbolic trajectory will attain at infinity an orbital velocity called hyperbolic excess velocity () that can be computed as:

where:

- is the standard gravitational parameter,

- is the (negative) semi-major axis of orbit's hyperbola.

The hyperbolic excess velocity is related to the specific orbital energy or characteristic energy by

is commonly used in planning interplanetary missions.

Velocity

Under standard assumptions the orbital speed () of a body traveling along a hyperbolic trajectory can be computed from the vis-viva equation as:

where:

- is standard gravitational parameter,

- is radial distance of orbiting body from central body,

- is the (negative) semi-major axis.

Under standard assumptions, at any position in the orbit the following relation holds for orbital velocity (), local escape velocity () and hyperbolic excess velocity ():

Note that this means that a relatively small extra delta-v above that needed to accelerate to the escape speed results in a relatively large speed at infinity. For example, at a place where escape speed is 11.2 km/s, the addition of 0.4 km/s yields a hyperbolic excess speed of 3.02 km/s.

Angle between approach and departure

Let the angle between approach and departure (between asymptotes) be .

- and

where:

- is the orbital eccentricity, which is greater than 1 for hyperbolic trajectories.

Distance of closest approach

The distance of closest approach, also called the periapse distance and the focal distance, is given by

Energy

Under standard assumptions, specific orbital energy () of a hyperbolic trajectory is greater than zero and the orbital energy conservation equation for this kind of trajectory takes form:

where:

- is orbital velocity of orbiting body,

- is radial distance of orbiting body from central body,

- is the (negative) semi-major axis,

- is standard gravitational parameter.

Radial hyperbolic trajectory

A radial hyperbolic trajectory is a non-periodic trajectory on a straight line where the relative speed of the two objects always exceeds the escape velocity. There are two cases: the bodies move away from each other or towards each other. This is a hyperbolic orbit with semi-minor axis = 0 and eccentricity = 1. Although the eccentricity is 1 this is not a parabolic orbit.

Relativistic two-body problem

In context of the two-body problem in general relativity, trajectories of objects with enough energy to escape the gravitational pull of the other, no longer are shaped like an hyperbola. Nonetheless, the term "hyperbolic trajectory" is still used to describe orbits of this type.

See also

References

- Vallado, David A. (2007). Fundamentals of Astrodynamics and Applications, Third Edition. Hawthorne, CA.: Hawthorne Press. ISBN 978-1-881883-14-2.

External links

- http://homepage.mac.com/sjbradshaw/msc/traject.html

- http://www.go.ednet.ns.ca/~larry/orbits/ellipse.html

- http://www.braeunig.us/space/orbmech.htm#hyperbolic