Cthulhu Mythos

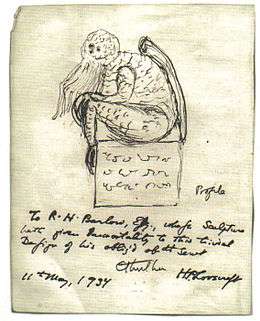

The Cthulhu Mythos is a shared fictional universe, based on the work of American horror writer H. P. Lovecraft.

The term was first coined by August Derleth, a contemporary correspondent of Lovecraft, who used the name of the creature Cthulhu—a central figure in Lovecraft literature[1] and the focus of Lovecraft's short story "The Call of Cthulhu" (first published in pulp magazine Weird Tales in 1928)—to identify the system of lore employed by Lovecraft and his literary successors. The writer Richard L. Tierney later applied the term "Derleth Mythos" to distinguish between Lovecraft's works and Derleth's later stories.[2]

Authors of Lovecraftian horror use elements of the Mythos in an ongoing expansion of the fictional universe.[3]

History

In his essay "H. P. Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos," Robert M. Price described two stages in the development of the Cthulhu Mythos. Price called the first stage the "Cthulhu Mythos proper." This stage was formulated during Lovecraft's lifetime and was subject to his guidance. The second stage was guided by August Derleth who, in addition to publishing Lovecraft's stories after his death,[4] attempted to categorize and expand the Mythos.[5]

First stage

An ongoing theme in Lovecraft's work is the complete irrelevance of mankind in the face of the cosmic horrors that apparently exist in the universe. Lovecraft made frequent reference to the "Great Old Ones": a loose pantheon of ancient, powerful deities from space who once ruled the Earth and who have since fallen into a deathlike sleep.[6] This was first established in "The Call of Cthulhu", in which the minds of the human characters deteriorated when afforded a glimpse of what exists outside their perceived reality. Lovecraft emphasized the point by stating in the opening sentence of the story that "The most merciful thing in the world, I think, is the inability of the human mind to correlate all its contents."[7]

Writer Dirk W. Mosig notes that Lovecraft was a "mechanistic materialist" who embraced the philosophy of cosmic indifferentism. Lovecraft believed in a purposeless, mechanical, and uncaring universe. Human beings, with their limited faculties, could never fully understand this universe, and the cognitive dissonance caused by limitation leads to insanity. Lovecraft's viewpoint made no allowance for religious belief which could not be supported scientifically, with the incomprehensible, cosmic forces of his tales having as little regard for humanity as humans have for insects.[8][9]

There have been attempts at categorizing this fictional group of beings. Phillip A. Schreffler argues that by carefully scrutinizing Lovecraft's writings, a workable framework emerges that outlines the entire "pantheon" – from the unreachable "Outer Ones" (e.g. Azathoth, who apparently occupies the centre of the universe) and "Great Old Ones" (e.g. Cthulhu, imprisoned on Earth in the sunken city of R'lyeh) to the lesser castes (the lowly slave shoggoths and the Mi-go).[10]

David E. Schultz, however, believes Lovecraft never meant to create a canonical Mythos but rather intended his imaginary pantheon to merely serve as a background element.[11] Lovecraft himself humorously referred to his mythos as "Yog Sothothery" (Mosig coincidentally suggested the term Yog-Sothoth Cycle of Myth be substituted for Cthulhu Mythos[12][13]). At times, Lovecraft had to remind readers that his mythos creations were entirely fictional.[14]

The view that there was no rigid structure is reinforced by S. T. Joshi, who stated "Lovecraft's imaginary cosmogony was never a static system but rather a sort of aesthetic construct that remained ever adaptable to its creator's developing personality and altering interests... [T]here was never a rigid system that might be posthumously appropriated... [T]he essence of the mythos lies not in a pantheon of imaginary deities nor in a cobwebby collection of forgotten tomes, but rather in a certain convincing cosmic attitude."[15]

Price, however, believed that Lovecraft's writings could at least be divided into categories and identified three distinct themes: the "Dunsanian" (written in the vein of Lord Dunsany), "Arkham" (occurring in Lovecraft's fictionalized New England setting), and "Cthulhu" (the cosmic tales) cycles.[16] Writer Will Murray noted that while Lovecraft often used his fictional pantheon in the stories he ghostwrote for other authors, he reserved Arkham and its environs exclusively for those tales he wrote under his own name.[17]

Although not formalized and acknowledged as a mythos per se, Lovecraft did correspond with contemporary writers Clark Ashton Smith, Robert E. Howard, Robert Bloch, Frank Belknap Long, Henry Kuttner, and Fritz Leiber – a group referred to as the "Lovecraft Circle" – and shared story elements:[18][19] Robert E. Howard's character Friedrich Von Junzt reads Lovecraft's Necronomicon in the short story "The Children of the Night" (1931), and in turn Lovecraft mentions Howard's Unaussprechlichen Kulten in the stories "Out of the Aeons" (1935) and "The Shadow Out of Time" (1936).[20] Many of Howard's original unedited Conan stories also form part of the Cthulhu Mythos.[21]

Second stage

Price's dichotomy dictates the second stage commenced with August Derleth. The principal difference between Lovecraft and Derleth being the latter's use of hope and that the Cthulhu mythos essentially represented a struggle between good and evil.[22] Derleth is credited with creating the Elder Gods. He stated:

As Lovecraft conceived the deities or forces of his mythos, there were, initially, the Elder Gods... [T]hese Elder Gods were benign deities, representing the forces of good, and existed peacefully...very rarely stirring forth to intervene in the unceasing struggle between the powers of evil and the races of Earth. These powers of evil were variously known as the Great Old Ones or the Ancient Ones...

—August Derleth, "The Cthulhu Mythos"[23]

Price suggests that the basis of Derleth's systematization is found in Lovecraft, stating: "Was Derleth's use of the rubric 'Elder Gods' so alien to Lovecraft's in At the Mountains of Madness? Perhaps not. In fact, this very story, along with some hints from 'The Shadow over Innsmouth', provides the key to the origin of the 'Derleth Mythos'. For in At the Mountains of Madness we find the history of a conflict between two interstellar races (among others): the Elder Ones and the Cthulhu-spawn."[24] Derleth himself believed that Lovecraft wished for other authors to actively write about the myth-cycle as opposed to it being a discrete plot device.[25] Derleth expanded the boundaries of the Mythos by including any passing reference to another author's story elements by Lovecraft as part of the genre: just as Lovecraft made passing reference to Clark Ashton Smith's Book of Eibon, Derleth in turn added Smith's Ubbo-Sathla to the Mythos.[26]

Derleth also attempted to connect the deities of the Mythos to the four elements (air, earth, fire, and water), but was forced to adopt artistic license and create beings to represent certain elements (air and fire) to legitimize his system of classification.[27] In applying the elemental theory to beings that function on a cosmic scale (e.g. Yog-Sothoth) some authors created a separate category termed aethyr.

| Air | Earth | Fire | Water |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hastur* Ithaqua* Nyarlathotep Zhar and Lloigor* |

Cyäegha Nyogtha Shub-Niggurath Tsathoggua |

Aphoom-Zhah Cthugha* |

Cthulhu Dagon Ghatanothoa Mother Hydra Zoth-Ommog |

| * Deity created by Derleth. | |||

"Lovecraft" mythos

A lesser known term employed by the scholar S. T. Joshi to describe the works of Lovecraft.[28] Joshi identified four key elements in Lovecraft's mythos (that Price would later condense to three themes), being the fundamental principle of cosmicism (which once again highlighted the irrelevance of mankind), the imaginary New England setting, a pantheon of recurring "pseudomythological" entities and a collection of arcane books that supposedly yield insights into the mythology.[28]

See also

- Cthulhu Mythos anthology

- Cthulhu Mythos arcane literature

- Cthulhu Mythos biographies

- Cthulhu Mythos deities

- Cthulhu Mythos in popular culture

- Dreamlands

- Elements of the Cthulhu Mythos

- The King in Yellow - An 1895 book of short stories by Robert W. Chambers that was a source of inspiration for the Cthulhu Mythos.

- Weird fiction

Notes

- ↑ "Cthulhu Elsewhere in Lovecraft," Crypt of Cthulhu #9

- ↑ Cf. Richard L. Tierney, "The Derleth Mythos", Discovering H. P. Lovecraft, p. 52.

- ↑ Harms, "A Brief History of the Cthulhu Mythos", The Encyclopedia Cthulhiana, pp. viii–ix.

- ↑ Bloch, "Heritage of Horror", p. 8.

- ↑ Price, "H. P. Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos", Crypt of Cthulhu #35, p. 5.

- ↑ Harms, "A Brief History of the Cthulhu Mythos", p. viii.

- ↑ HP Lovecraft, "The Call of Cthulhu" (1928).

- ↑ Mosig, Yozan Dirk W. "Lovecraft: The Dissonance Factor in imaginary Literature" (1979).

- ↑ Mariconda, "Lovecraft's Concept of 'Background'", pp. 22–3, On the Emergence of "Cthulhu" & Other Observations.

- ↑ Shreffler, Phillip A. (1977). The H. P. Lovecraft Companion, pp. 156–157.

- ↑ Schultz, "Who Needs the Cthulhu Mythos?", A Century Less A Dream, pp. 46, 54.

- ↑ (Mosig, Yozan Dirk W. (1997). Mosig at Last: A Psychologist Looks at H. P. Lovecraft, p. 28)

- ↑ "Yog-Sothothery". Timpratt.org. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ↑ Price, "Lovecraft's 'Artificial Mythology'", pp. 251, 253; Mariconda, "Toward a Reader-Response Approach to the Lovecraft Mythos", On the Emergence of "Cthulhu" & Other Observations, pp. 33–4.

- ↑ Lovecraft, H.P. "In Defense of Dagon" reprinted in Miscellaneous Writings (S. T. Joshi, ed.) Sauk City: Arkham, 1995; pp. 165–66

- ↑ Price, "H. P. Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos", Crypt of Cthulhu #35, p. 9.

- ↑ (Murray, "In Search of Arkham Country I", pp. 105, 107.)

- ↑ Joshi, ST (1980). HP Lovecraft, four decades of criticism. Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-0577-2.

- ↑ D'Ammassa, Don (1996). "Henry Kuttner: Man of Many Voices". In Darrell Schweitzer. Discovering Classic Fantasy Fiction: Essays on the Antecedents of Fantastic Literature. Wildside Press, LLC. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-58715-004-3.

- ↑ Price, "H. P. Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos", Crypt of Cthulhu #35, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Patrice Louinet. Hyborian Genesis: Part 1, page 436, The Coming of Conan the Cimmerian; 2003, Del Rey.

- ↑ Bloch, "Heritage of Horror", p. 9.

- ↑ Derleth, "The Cthulhu Mythos", Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos, p. vii.

- ↑ "Lovecraft-Derleth Connection". Crypt-of-cthulhu.com. Retrieved 2012-11-28.

- ↑ Schultz, "Who Needs the Cthulhu Mythos?", pp. 46–7.

- ↑ Price, "H. P. Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos", Crypt of Cthulhu #35, pp. 6–10.

- ↑ Derleth created "Cthugha" when fan Francis Towner Laney claim Derleth had neglected to include a fire elemental in his schema. Laney, the editor of The Acolyte, had categorized the Mythos in an essay that first appeared in the Winter 1942 issue of the magazine. Impressed by the glossary, Derleth asked Laney to rewrite it for publication in the Arkham House collection Beyond the Wall of Sleep (1943). (Robert M. Price, "Editorial Shards", Crypt of Cthulhu #32, p. 2.) Laney's essay ("The Cthulhu Mythos") was later republished in Crypt of Cthulhu #32 (1985).

- 1 2 "The Lovecraft Mythos", H. P. Lovecraft, p. 31ff. Joshi acknowledges, however, that Donald R. Burleson independently coined the term in his eponymous article that appears in Magill's Survey of Science Fiction Literature, volume III (see References section for a detailed citation), p. 1284ff. (H. P. Lovecraft, p. 68, footnote no. 52.)

References

Books

- Bloch, Robert (1982). "Heritage of Horror". The Best of H. P. Lovecraft: Bloodcurdling Tales of Horror and the Macabre (1st ed.). Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-35080-4.

- Bloch, Robert (1978). Strange Eons. Whispers Press. ISBN 978-0-918372-30-7.

- Derleth, August (1969). "The Cthulhu Mythos". Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos. Sauk City, WI: Arkham House.

- Burleson, Donald R. (1979). "The Lovecraft Mythos". In Frank N. Magill (ed.). Survey of Science Fiction Literature (Vol. 3 ed.). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Salem Press. pp. 1284–8. ISBN 978-0-89356-197-0.

- Harms, Daniel (1998). The Encyclopedia Cthulhiana (2nd ed.). Chaosium, Inc. ISBN 978-1-56882-119-1.

- Jens (ed.), Tina (1999). Cthulhu and the Coeds: Kids and Squids. Chicago, IL: Twilight Tales.

- Joshi, S. T. (1982). H. P. Lovecraft (1st ed.). Mercer Island, WA: Starmont House. ISBN 978-0-916732-36-3.

- Lovecraft, Howard P. (1999) [1928]. "The Call of Cthulhu". In S. T. Joshi (ed.). The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. London, UK; New York, NY: Penguin Books.

- Mosig, Yozan Dirk W. (1997). Mosig at Last: A Psychologist Looks at H. P. Lovecraft (1st printing ed.). West Warwick, RI: Necronomicon Press. ISBN 978-0-940884-90-8.

- Murray, Will (January 1999). "In Search of Arkham Country I". In James Van Hise (ed.). The Fantastic Worlds of H. P. Lovecraft. Yucca Valley, CA: James Van Hise. No ISBN.

- Price, Robert M. (1996). "Introduction". In Robert M. Price (ed.). The New Lovecraft Circle. New York, NY: Random House, Inc. ISBN 978-0-345-44406-6.

- Price, Robert M. (1991). "Lovecraft's 'Artificial Mythology'". In David E. Schultz and S. T. Joshi (ed.). An Epicure in the Terrible: a centennial anthology of essays in honor of H. P. Lovecraft. Rutherford, NJ and Cranbury, NJ: Fairleigh Dickinson University Press and Associated University Presses. ISBN 978-0-8386-3415-8.

- Schultz, David E. (2002) [1987]. "Who Needs the Cthulhu Mythos?". In Scott Conners (ed.). A Century Less a Dream: Selected Criticism on H. P. Lovecraft (1st ed.). Holikong, PA: Wildside Press. ISBN 978-1-58715-215-3.

- Schweitzer, Darrell (ed.) (2001). Discovering H. P. Lovecraft. Helicong, PA: Wildside Press. ISBN 978-1-58715-471-3.

- Shreffler, Phillip A. (1977). The H. P. Lovecraft Companion. Westport, CT and London, England: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-8371-9482-0.

- Turner, James (1998). "Iä! Iä! Cthulhu Fhtagn!". Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (1st ed.). Random House. ISBN 978-0-345-42204-0.

- Thomas, Frank Walter (2005). Watchers of the Light, (1st printing ed.). Lake Forest Park, WA: Lake Forest Park Books. ISBN 978-0-9774464-0-7.

Journals

- August, Derleth (Lammas 1996) [1937]. "H. P. Lovecraft—Outsider". Crypt of Cthulhu. 15 (3). Check date values in:

|date=(help) Robert M. Price (ed.), West Warwick, RI: Necronomicon Press. Original publication: Derleth (June 1937). "H. P. Lovecraft—Outsider". River. 1 (3). - Dziemianowicz, Stefan (Eastertide 1992). "Divers Hands". Crypt of Cthulhu. 11 (2). Check date values in:

|date=(help) Robert M. Price (ed.), West Warwick, RI: Necronomicon Press. - Price, Robert M. (Hallowmas 1985). "H. P. Lovecraft and the Cthulhu Mythos". Crypt of Cthulhu. 5 (1). Check date values in:

|date=(help) Robert M. Price (ed.), Mount Olive, NC: Cryptic Publications.

Further reading

- Dziemianowicz, Stefan. "The Cthulhu Mythos: Chronicle of a Controversy". In The Lovecraft Society of New England (ed) Necronomicon: The Cthulhu Mythos Convention 1993 (convention book). Boston, MA: NecronomiCon, 1993, pp. 25–31

- Carter, Lin (1972). Lovecraft: A Look Behind the Cthulhu Mythos. New York, NY: Ballantine Books. ISBN 0-345-02427-3.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cthulhu Mythos. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Cthulhu Mythos |

- Lovecraft Archive

- Joshi, S. T. "H. P. Lovecraft". The Scriptorium. Retrieved July 20, 2005.

- The Virtual World of H. P. Lovecraft a mapping of Lovecraft's imaginary version of New England