Résistance Joué-du-Plain and the Assassination of Emile Buffon

The French Résistance of Joué-du-Plain, and the assassination of Emile Buffon.[1][2][3]

The events concerns two tenants of Chateau de la Motte during World War II in Lower Normandy, France. The first was the mayor of the commune of Joue du Plain, Emile Buffon, who owned an animal brokering business, and rented the Chateau’s attached farm.[4] Secondly there was Jacques Batchlier, who rented two buildings next to the main house, and had a dairy business.

Batchlier lived in Chateau de la Motte with his wife, Denise. Emile Buffon lived at a rented farm about two kilometers away called Mancelaire.[5]

Up until 1944, Normandy had been less disturbed by the War. The rich farmland permitted locals to live much better than those living with chronic shortages in cities. Long lost cousins in the countryside suddenly found themselves with many new relatives wanting to rekindle their rural roots. German troops assigned to the Normandy often cooperated with locals in order not to attract unwanted attention from Nazi administrators. All this changed in 1944.[6]

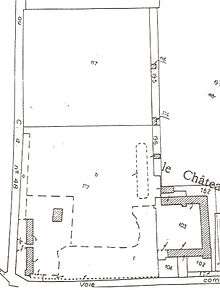

Arms depot at Chateau de la Motte, Joué du Plain

In spring of 1944, all of Europe knew that an Allied invasion was imminent, but the time and place were unknown. Germany buttressed its anti-résistance forces and moved large numbers of the Gestapo into to France in January 1944.The results were numerous arrests, killings and deportations to Nazi concentration camps.[7][8]

The Germans, in a chronic need for manpower, had discontinued the voluntary worker immigration for the Fatherland’s war factories, and made it mandatory (STO Service du Travail Obligatoire), avoidance brought death. Eight young men in nearby Râne, were shot by firing squad to be an example. The Germans didn’t negotiate.

April 27, 1944, a little over one month before D-day, the regional French Résistance chief, Jacques Foccart, with his lieutenant sitting behind him, drove an 8-cylinder Nervasport from the Chateau de la Motte. Jacques Batchlier sat in the passenger’s seat. He owned the dairy, but rented the buildings at Chateau de la Motte, which he used as a base for the local Resistance. The car road low, heavy with weapons and explosives intending to be used as part of a “Plan Tortue” (turtle plan) to slow the German armored divisions from reinforcing their defenses no matter where the Allies landed.[9]

It was night and they slowed as their approached a German roadblock. Just as the driver reached the critical point of no return he accelerated, and crashed through the barricade, a blast of machine-gun fire ripped across the back to vehicle. The man behind the driver slumped over with a bullet in his spine.[10]

Now in their worst-case scenario the two partisans sped toward town of Écouché as German soldiers raced to catch them. The disaster plan that unfolded was to elude the predators by passing in front of a scheduled train, as it passed through town. Just as the Germans were catching up with the Nervasport, the Frenchmen turned across the tracks narrowly missing the oncoming train, which blocked the pursuit.[11]

They had a few minutes of precious time, but a fatally wounded comrade, a now known vehicle, and a trunk load of weapons to hide.

They drove to a crossroad and fired several shots, knowing that witnesses would be called on to verify the sound later in an investigation, which was sure to follow. They then drove to the farm, Viganière, near Chateau de la Motte. Jules Christophe, a member of the Resistance hid them. Following hasty instructions they parked the car in a barn, Foccart borrowed a bike to pedal into Ecouche to find the doctor Pasquier, a member of the Résistance.[12]

Later the doctor told the Germans, that an unknown woman on a bike had informed him of finding a still living body on the roadside at the crossroads, where they fired the pistol. Disaster had been delayed for the immediate future.[13]

Cars were by permit only, and a Nervasport was more rare still. Only one was registered in the area. They Germans now knew what to look for it: the dairy at Chateau de la Motte had the only local car known.[14]

De Gaulle and the Resistance goals

Neither the Allies nor General Charles de Gaulle, encouraged sabotage and armed resistance except just before the Invasion. Attracting Nazi attention with untrained amateur warriors would only jeopardize the more desirable intelligence gathering by the French underground, learning critical information on size, strength, and location of enemy troops.[15]

The arms depot consisted of mostly anti-tank weapons, which were intended to kink up the Nazi reaction time by delaying the Panzer divisions of tanks the Germans would send to the landing sites. A few days delay were critical. By the time of D-day two thirds of the Normandy rail lines were sabotaged and mostly useless to the Germans. Weapons consisted of mines, railway explosives, hand grenades, bazookas, and various small arms to protect the saboteurs.[16]

Collaborator Bernard Jardin

What the local French didn’t know was to come to stab them in the back over and over again. First a local Frenchman had been recently arrested for black market activities was converted to the German cause.

The collaborator Bernard Jardin lived with his mother, a local café owner. Smart, energetic and ambitious, he knew how to get the hard information, and cruelty came easily to him. He personally killed 4 Frenchmen he suspected of being Resistance. His conversion came in April 1944.[17]

May 10, a few weeks before D-day, June 6, the second jab came from Nazi breaking into an office in Angers, an hour to the south of Ecouche by car. There a list of names brought arrest and torture. Capture and torture bought more names and one was the name and description of a small man named Bachelier who ran a dairy in Joué du Plain. His dairy operated in the two buildings at Chateau de la Motte.[18]

May 12, M. Bachelier saw the Germans roar into the Chateau farmyard and he knew he had been found out. He jumped out of the bedroom window escaping across the road into a nearby forest.[19]

The soldiers didn’t find the weapons, but took Yvonne,Bachelier's wife in for questioning, Bernard Jardin offered her dinner with champagne, but under the circumstances she declined. Five hours later she returned home.[20]

The Germans then went in search of Bachelier's sister and brother, Denise and Maurice. Finding the sister just as she arrived back from delivering rescued American pilot Charles Moore to a safer hideout after hiding him at the Chateau. Both brother and sister were sent to the death camp, Ravenstracht, near Berlin.[21][22]

Other names found in Angers brought the downfall of many of Résistants in the neighboring town of Argentan. Most of them soon died in Nazi concentration camps only months before the War’s end, others died after the French liberation as a result of the inhuman conditions there.

The Germans now knew about the “Plan Tortue”. The doctor’s false excuse for finding the bullet ridden partisan died with the patient. The German autopsy revealed a German bullet in the spine. The Gestapo then knew that the dead man was from the suspected vehicle, and it was sure to be carrying weapons. An “armes despot” nearby seemed likely, and Chateau de la Motte had enough scattered buildings to hide anything.[23]

D-day

June 6 followed days later: The Longest Day, D-day, began. One and half million men assaulted and crowded onto the beaches of Normandy. It took six weeks for the American forces to finally break out of the German containment at the battle of St.Lo on July 25.[24]

The Nazi machine cranked on even as Patton’s army swept first west then south around and encircled the German army. Local French knew the occupiers’ days were numbered and they grew braver, but German retaliation grew more desperate and cruel. Entire French communities were killed; the most famous being the massacre d'Oradour-sur-Glane. [25] In Joué du Plain, within an easy two-hour drive from those landing beaches, Nazi power remained strong and tenacious.

Meanwhile, the Germans found nothing at the Chateau.[26]

Emile Buffon, Mayor of Joué du Plain

Mayor Buffon was an animal dealer. Part of his business consisted of gathering animals for the Germans. It was an unwelcome job, but mandated by the Germans as well as his unasked role as mayor. However, like many older patriotic French, he was Vichy supporter, a decorated World War I veteran. Although gassed in the Great War, he was a large, healthy man. As a well-liked community member he was trying to make the best of a difficult time.[27]

As part of the armistice with Germany, France had agreed to pay for their defeat. Much of that was providing farm animals and produce to the occupiers; personal trucks, cars and horses had all been confiscated several years before just after the French defeat in 1939. At the same time as he benefited from working with the Germans, he was in a position to know information when it was rare and valuable.[28]

Emile Buffoon had family besides his daughter and wife; his brother, Georges Buffon and his two sons Jean and René, had the Metz farm next to Emile's. However blood was all they shared. An unexplained animosity separated the two since childhood. Emile Buffon was in a position of knowing too much from all sides. His brother, Georges, along with his two sons were active members of the Résistance, and it was to them that Jacques Bachelier took his anger of his suspected betrayal.[29]

A few days before the first raid on Chateau de la Motte by the Gestapo, someone had hinted to Emile Buffon that he should check his pigs in the chateau barn. Mayor Buffon found a weapons hoard. He found Batchelier and insisted he move the weapons. Several days later the Germans tipped off by the Angers capture mentioned earlier, arrived in force. However, Bachelier believed he knew his traitor.[30]

Bachelier had already moved the munitions to another Chateau building; a day worker's house in the orchard. A long window where cows could put their head into and eat from a trough accessed the lower floor. Entry was difficult except for a small man who could crawl in and dig under the animal feed and pass the arms out through the window.[31]

During the night of July 14, 1400 kilograms, or one and half tons of weaponry, were hauled across country under the short night of the Norman summer. Later witnesses said the remainder was dumped in the Chateau’s fishponds.[32]

From there the resistants moved the hidden cache south near Râne. In later court testimony, Gabriel Ramier said that he drove the arms to Bachilier mother’s farm, outside the region to the south. Ramier had a truck because he worked for a stonemason contracted with the German TODT Corporation, hired to build the Atlantic Wall, the thousand mile coastal fortress, designed to stop any Allied Invasion. M. Ramier said there was plenty of work if you would work for the Germans, and now his truck carrying weapons buried under the sacks of cement was the payoff.[33]

Timeline: Spring and summer 1944

Resistance activity, significant events, and assassination time line.

April

- April 27 – Barcade run and German suspicions aroused

- April 30 – P-51 Mustang of Charles Moore, American fighter pilot shot down near Écouché.

May

- May. 10 –The Germans capture many of the Resistance of French town of Angers. The torture reveals names throughout the region. More arrests and tortures began.

- May 11 – Germans raid Chateau de la Motte looking for weapons depot.

- May 21 – Denise and Maurice, sister and brother of M.Batchlier arrested and sent to concentration camp

- May 22 – The doctor Pasquier and Jules Christophe arrested

- May 22 – British agent "Sideral" arrives in Seine region.

June

- June 6 – D-day

- June 6 – Lancaster bombers aiming at the Écouché train station bomb the town killing 53 residents.

- June 11 – Metz- Emile Buffon was condemned to death by 12 Resistants, including his brother and nephews

- June 13 – German convoy attacked near Francheville/Bouche

- June 16 – Emile Buffon assassination

- June 28 – Spitfire of George Murray shot down near Briouze.

- June 30—Telephone lines cut Écouché at the Cross of Libardon

July

- July 2 – Two Resistants killed at Les Genettes- woman denounces her boss to the Germans

- July 7 – Spitfire of pilot Norman Baker shot down.

- July 12- Second bombardment Alençon, Argentan, Écouché – 51 civilians killed

- July 16 – German Messerschmitt 109 shotdown at Chateau de la Motte

- July 18 – P47 Thunderbolt of Capt.Beaman shot down near Mesnil Jean –

August

- Aug 1 – St.Ouen-sur-Orne. American fighter shotdown.

- Aug 7 - Mortain counterattract by Germans ordered by Adolf Hitler.

- Aug 7- Operation Totalize to take Falaise

- Aug 10-11 – Parachutage of weapons for the Resistance at Levite near Rânes

- Aug 12 - General George Patton takes Alençon

- Aug 13-14 – Free French 2nd Armored Division under Patton forces take Écouché

- Aug 14- British-CanadianOperation Tractable takes Falaise

- Aug 15 – Americans and French invade southern France at Province

- Aug 17 – Flers, Athis, Briouze taken and 31 locals killed

- Aug 17- New German commander Field Marshal Walter Model orders retreat toward Falaise.

- Aug 18 – Putages taken by Allies, 23 locals killed

- Aug 19 – Menil Hermes – artillery kill 22 locals hiding in a trench.

See also

References

- ↑ Miniac, Jean-François (2008). Les Grandes Affaires Criminelles de l'Orne. Paris: Éditions De Borée. pp. 153–177. ISBN 978-2-84494-814-4.

- ↑ Robine, Stéphane (2005). "Les Résistants du Brocage Ornais". Le Pays Bas-Normand. quartre année de lutte clandestine. 2 (N 259-260): 24,142–147,182.

- ↑ Robine, Stéphane (2004). "Les Résistants du Bocage Ornais". Le Pays Bas-Normand. Quatre années de lutte clandestine. 1 (254-255-256): 174–196.

- ↑ Miniac,2008,

- ↑ Miniac,2008,

- ↑ Vinen, Richard (2007). The Unfree French:Life Under the Occupation. London: Penguin. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-14-029684-6.

- ↑ Robine, Stephane (Sep 2005). "Les Resistants du Bocage Ornais". Le Pays Bas-Normand. Quartre annees de lutte clandestine. 2 (259-260): 7. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help); - ↑ Vinen, Richard (2007). The Unfree French. London: Penguin. p. 109. ISBN 978-0-14-029684-6.

- ↑ Miniac, Jean-François (2007). Les Grandes Affaires Criminelles de l'Orne. Paris: De Boré. p. 158. ISBN 978-2-84494-814-4.

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 158

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 158

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 158

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 158

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 159

- ↑ Schoenbrun, David (1980). Soldiers of the Night. New York: Meridian. p. 317.

- ↑ Schoenbrun, 1980,page 310

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 200

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 159

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 160

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 160

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 164

- ↑ Robine, Stéphane (2004). "Les Resistants du Bocage Ornais". Le Pays Bas-Normand. Quatre annees de lutte clandestine. 97:1 (254-255-256): 188.

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 160

- ↑ Keegan, John (2004). Six Armies at Normandy. London: Pimlico. p. 232. ISBN 1-84413-739-2.

- ↑ Vinen,2007,page 327

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 164

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 153-4

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 167

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 158

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 163

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 163

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 164

- ↑ Miniac,2008,page 163

- ↑ Mazeline, André (1994). Clandestinité. Paris: Editions Tirésias. pp. ,53–62,152,169. ISBN 2-908527-22-7.

- ↑ Miniac, 2008,153-179

External links

- http://www.ansa39-45.fr/mooreenglish.htm English website of the memoirs of American P 51 pilot Charles Moore. He was not aware of the above events and doesn't remember where he was hidden but local memoirs place him at Chateau de la Motte.