Classical Arabic

| Classical Arabic | |

|---|---|

| Native to | Historically in the Middle East, now used as a liturgical language of Islam |

| Era | 4th to 9th centuries; continues as a liturgical language but with a modernized pronunciation |

|

Afro-Asiatic

| |

Early forms |

Old Arabic

|

| Dialects | Over 24 modern Arabic dialects |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

| Glottolog | None |

|

| |

Classical Arabic (CA), also known as Quranic Arabic or occasionally Mudari Arabic, is the form of the Arabic language used in literary texts from Umayyad and Abbasid times (7th to 9th centuries). It is based on the medieval dialects of Arab tribes. Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is the direct descendant used today throughout the Arab world in writing and in formal speaking, for example, prepared speeches, some radio broadcasts, and non-entertainment content.[1] While the lexis and stylistics of Modern Standard Arabic are different from Classical Arabic, the morphology and syntax have remained basically unchanged (though MSA uses a subset of the syntactic structures available in CA).[2] The vernacular dialects, however, have changed more dramatically.[3] In the Arab world, little distinction is made between CA and MSA, and both are normally called al-fuṣḥá (الفصحى) in Arabic, meaning 'the most eloquent (Arabic language)'.

Because the Quran is in Classical Arabic, the language is considered by most Muslims to be sacred.[4]

History

Classical Arabic has its origins in the central and northern parts of the Arabian Peninsula, and is distinct from the Old South Arabian languages that were spoken in the southern parts of the peninsula, modern day Yemen.[5] Classical Arabic co-existed with the Old North Arabian languages. In the 5th century BC, Herodotus (Histories I,131; III,8) quotes the epithet of a goddess in its preclassical Arabic form as Alilat (Ἀλιλάτ, i. e.,ʼal-ʼilat).[6] Apart from this isolated theonym, Arabic is first attested in an inscription in Qaryat al-Fāw (formerly Qaryat Dhat Kahil, near Sulayyil, Saudi Arabia) in the 1st century BC.[7][8] The oldest inscription in Classical Arabic dates to 328 AD and is known as the Namārah inscription, written in the Nabataean alphabet and named after the place where it was found in southern Syria in April 1901.[9]

With the spread of Islam, Classical Arabic became a prominent language of scholarship and religious devotion as the language of the Quran (at times even spreading faster than the religion).[3] Its relation to modern dialects is somewhat analogous to the relationship of Vulgar Latin to the Romance languages or of Old Spanish to modern Spanish dialects or of Middle Chinese to modern varieties of Chinese.

Morphology

Classical Arabic is one of the Semitic languages and so has many similarities in conjugation and pronunciation to Assyrian, Hebrew, Akkadian, Aramaic, and Amharic. Like all other Semitic languages, it has nonconcatenative morphology.

For example:

- كَتَبَ kataba, he wrote

- يَكْتُبُ yaktubu, he writes

- مَكْتُوبٌ maktūbun, written (words)

- كِتَابٌ kitābun, book

- كُتُبٌ kutubun, books (broken plural)

- كِتَابَةٌ kitābatun, writing

- كِتَابَاتٌ kitābātun, writings (feminine sound plural)

- مَكْتَبٌ maktabun, desk

- مَكْتَبَةٌ maktabatun, library

- كَاتِبٌ kātibun, writer

- كَاتِبُونَ kātibūna, writers (masculine sound plural)

- كُتَّّابٌ kuttābun, writers (broken plural)

- مِكْتَابٌ miktābun, writing machine

These words all have some relationship with writing, and all of them contain the three consonants KTB. This group of consonants k-t-b is called a root. Grammarians assume that the root carries a basic meaning of writing, which encompasses all objects or actions involving writing, and so all the above words are regarded as modified forms of this root and are "obtained" or "derived" in some way from it.

Grammar

| Part of a series on |

| Arab culture |

|---|

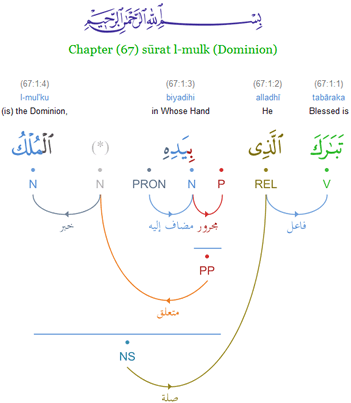

Descriptive grammar in Arabic (قَوَاعِد qawāʻid, 'rules'), underwent development in the late 8th century.[10][11] The earliest known Arabic grammarian is ʻAbd Allāh ibn Abī Isḥāq. The efforts of three successive generations of grammarians culminated in the book of the Persian scholar Sībawayhi. Recent efforts aim to annotate the entire Arabic grammar of the Quran, using traditional syntax:

Phonology

Classical Arabic had three pairs of long and short vowels: /a/, /i/, and /u/:

| Vowels | Short | Long | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| High | /i/ | /u/ | /iː/ | /uː/ |

| Low | /a/ | /aː/↓ | ||

Like Modern Standard Arabic, Classical Arabic had 28 consonant phonemes:

| Labial | Dental | Denti-alveolar | Palatal | Velar | Uvular | Pharyngeal | Glottal | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plain | emphatic | |||||||||

| Nasal | m م | n ن | ||||||||

| Plosive | voiceless | t ت | tˠ1 ط | k ك | qˠ2 ق | ʔ ء↓ | ||||

| voiced | b ب | d د | ɟ4 ج | |||||||

| Fricative | voiceless | f ف | θ ث | s3 س | sˠ ص | ɕ ش | χˠ خ | ħ ح | h ه | |

| voiced | ð ذ | z ز | ðˠ ظ | ʁˠ غ | ʕ ع | |||||

| Lateral | l~k5 ل | ɮˠ ض | ||||||||

| Tap | r6 ر | |||||||||

| Approximant | j ي↓ | w و↓ | ||||||||

- ^1 Sibawayh described the consonant ⟨ط⟩ as voiced, but some modern linguists cast doubt upon this testimony.[13]

- ^2 Ibn Khaldun described the pronunciation of the ⟨ق⟩ as a voiced velar /g/ and that it might have been the old Arabic pronunciation of the letter, he even describes that prophet Muhammad may have had the /g/ pronunciation.[14]

- ^3 Non-emphatic /s/ may have actually been [ʃ],[15] shifting forward in the mouth before or simultaneously with the fronting of the palatals (see below).

- ^4 As it derives from Proto-Semitic *g, /ɟ/ may have been a palatalized velar: /ɡʲ/.

- ^5 /l/ is emphatic ([ɫ]) only in /ʔaɫɫɑːh/, the name of God, Allah,[16] except after /i/ or /iː/ when it is unemphatic: bismi l-lāhi /bismillaːhi/ ('in the name of God').

- ^6 /ɾˠ/ (velarized) is pronounced without velarization before /i/: [ɾ].

The consonants that are traditionally termed "emphatic" /sˤ, ɮˤ, tˤ, ðˤ/ were either velarized [sˠ, ɮˠ, tˠ, ðˠ] or pharyngealized [sˤ, ɮˤ, tˤ, ðˤ].[17] In some transcription systems, emphasis is shown by capitalizing the letter, for example, /sˤ/ is written ⟨S⟩; in others, the letter is underlined or has a dot below it, for example, ⟨ṣ⟩. The consonants [ɾˠ, qˠ, ʁˠ, χˠ] are pronounced with velarization.

There are a number of phonetic changes between Classical Arabic and modern Arabic dialects:[18]

- The palatals /ɕ/, /ɟ/ (⟨ش⟩, ⟨ج⟩) shifted. /ɕ/ became postalveolar [ʃ], and /ɟ/ became postalveolar [d͡ʒ] (or [ʒ], [ɡʲ], [ɟ], or velar [ɡ]).

- The uvular fricatives /χˠ/, /ʁˠ/ (⟨خ⟩, ⟨غ⟩) became velar or post-velar: [x], [ɣ] or left as they are but without velarization [χ], [ʁ].

- /ɮˤ/ ⟨ض⟩ became /dˤ/. See also Voiced alveolar lateral fricative

See Arabic phonology for further details of the IPA representations of contemporary Arabic sounds.

The language of Classical Arabic is essentially a standardized prestige dialect based on conservative dialects of the western Arabian peninsula. A similar but slightly different koine had been spoken in Mecca, in a form adapted somewhat to the phonology of the spoken Meccan dialect of the time, and it was the form that the Quran was given. It was later rephonemicized into the standard poetic koine. Two of the differences between the dialects are represented in the modern Arabic writing system:

- The original poetic standard Classical Arabic had preserved the Proto-Semitic glottal stop in all positions, but the Meccan variant had eliminated it everywhere except initially, following the spoken Meccan dialect. (Similar changes occur in all modern varieties of Arabic.) Depending on the surrounding vowels, the glottal stop was deleted entirely and converted to /w/ or /j/ or deleted after lengthening a preceding short vowel. The Quran as originally written down represented the changes; since the document was considered sacred, the letters were not changed. Instead, the letter representing the "incorrect" /w/, /j/ or long vowel that ought to be pronounced as a glottal stop had a diacritic (termed hamzah) written over it to cancel out its inherent sound; if no such letter existed, the hamzah was written between the existing letters. That is the origin of the complex rules regarding the writing of the glottal stop.

- In the dialects underlying the poetic koine, original word-final /aja, aji, aju/ had developed into /aː/, merging with final /aː/ from other sources. In the spoken Meccan dialect, however, these word-final sequences did not merge so but remained as a separate vowel, perhaps pronounced /eː/. Correspondingly, the Meccan koine variant split the standard koine's final /aː/ in two in ways that corresponded with the spoken dialect. To write the Meccan variant, final /aː/ was written with the letter alif, and final /eː/ was written with the letter yāʾ, normally used for /j/. When rephonemicized into the standard poetic koine, yāʼ is meant to be pronounced as /j/ or /aː/. Only recently, two dots was created to be written under the final yāʼ to distinguish it from the pronunciation of /aː/. That was not adopted by all Arabic speaking nations, as, for example, Egypt and Sudan never add two dots under the final yāʾ in handwriting and print, even in printed Qurans. Yāʾ, when used to spell /aː/, was named alif maqṣūrah (limited alif) or alif layyinah (flexible alif). That is why final /aː/ can be written either with a normal alif or an alif maqṣūrah.

Special symbols

Special symbols exist in the Classical Arabic of the Quran that are usually absent in most written forms of Arabic. Many serve as aids for readers attempting to accurately pronounce the Classical Arabic found in the Quran. They may also indicate prostrations (sujud), surahs, ayahs, or the ends of sections (rubʻ al-ḥizb).

| Code | Glyph | Name |

|---|---|---|

| 06D6 | ۖ | SMALL HIGH LIGATURE SAD WITH LAM WITH ALIF MAKSURA |

| 06D7 | ۗ | SMALL HIGH LIGATURE QAF WITH LAM WITH ALIF MAKSURA |

| 06D8 | ۘ | SMALL HIGH MEEM INITIAL FORM |

| 06D9 | ۙ | SMALL HIGH LAM ALIF |

| 06DA | ۚ | SMALL HIGH JEEM |

| 06DB | ۛ | SMALL HIGH THREE DOTS |

| 06DC | ۜ | SMALL HIGH SEEN |

| 06DD | | END OF AYAH |

| 06DE | ۞ | START OF RUB AL HIZB |

| 06DF | ۟ | SMALL HIGH ROUNDED ZERO |

| 06E0 | ۠ | SMALL HIGH UPRIGHT RECTANGULAR ZERO |

| 06E1 | ۡ | SMALL HIGH DOTLESS HEAD OF KHAH = Arabic jazm • used in some Qurans to mark absence of a vowel |

| 06E2 | ۢ | SMALL HIGH MEEM ISOLATED FORM |

| 06E3 | ۣ | SMALL LOW SEEN |

| 06E4 | ۤ | SMALL HIGH MADDA |

| 06E5 | ۥ | SMALL WAW |

| 06E6 | ۦ | SMALL YAA |

| 06E7 | ۧ | ARABIC SMALL HIGH YAA |

| 06E8 | ۨ | SMALL HIGH NOON |

| 06E9 | ۩ | PLACE OF SAJDAH |

| 06EA | ۪ | EMPTY CENTRE LOW STOP |

| 06EB | ۫ | EMPTY CENTRE HIGH STOP |

| 06EC | ۬ | ROUNDED HIGH STOP WITH FILLED CENTRE |

| 06ED | ۭ | SMALL LOW MEEM |

| From: Unicode Standard – Arabic | ||

See also

- Arabic language

- Modern Standard Arabic

- Ancient North Arabian

- Quranic Arabic Corpus

- Arabic–English Lexicon

Notes

- ↑ Bin-Muqbil 2006, p. 14.

- ↑ Bin-Muqbil 2006, p. 15.

- 1 2 Watson 2002, p. 8.

- ↑ "Arabic Language," Microsoft Encarta Online Encyclopedia 2009. "Classical Arabic, which has many archaic words, is the sacred language of Islam...". Archived 2009-10-31.

- ↑ "The Collapse of the Marib Dam and the Origin of the Arabs". Arabia Felix. March 30, 2005. Archived from the original on February 9, 2008.

- ↑ Woodard, Roger D. Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. p. 208.

- ↑ Woodard, Roger D. (2008). Ancient Languages of Syria-Palestine and Arabia. p. 180.

- ↑ Macdonald, M. C. A. (2000). Reflections on the Linguistic Map of Pre-Islamic Arabia. Arabian Archaeology and Epigraphy. 11. pp. 50 and 61.

- ↑ James A. Bellamy (1985). "A New Reading of the Namārah Inscription". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 105 (1): 31–51. doi:10.2307/601538. JSTOR 601538.

- ↑ Goodchild, Philip. Difference in Philosophy of Religion (2003), p. 153.

- ↑ Sayce, Archibald Henry. Introduction to the Science of Language (1880), p. 28.

- ↑ Watson 2002, p. 13.

- ↑ Danecki, Janusz (2008). "Majhūra/Mahmūsa". Encyclopedia of Arabic Language and Linguistics. III. Brill. p. 124.

- ↑ Heinrichs, Wolfhart. "Ibn Khaldūn as a Historical Linguist with an Excursus on the Question of Ancient gāf". Harvard University.

- ↑ Watson 2002, p. 15.

- ↑ Watson 2002, p. 16.

- ↑ Watson 2002, p. 2.

- ↑ Watson 2002, pp. 15–17.

References

- Bin-Muqbil, Musaed (2006). "Phonetic and Phonological Aspects of Arabic Emphatics and Gutturals". University of Wisconsin–Madison.

- Holes, Clive (2004) Modern Arabic: Structures, Functions, and Varieties Georgetown University Press. ISBN 1-58901-022-1

- Versteegh, Kees (2001) The Arabic Language Edinburgh University Press ISBN 0-7486-1436-2 (Ch.5 available in link below)

- Watson, Janet (2002). "The Phonology and Morphology of Arabic". New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bin Radhan, Neil. "Die Wissenschaft des Tadschwīd".

External links

| Look up Classical Arabic in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up Modern Standard Arabic in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Look up Fus-ha in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Learn Quran – Lectures on Quranic Arabic by Dr. Khalid Zaheer (CA)

- LearnArabicOnline – an authoritative, online project for Classical Arabic (CA)

- The Development of Classical Arabic

- The Arabic Alphabet

- Blog of Classical Arabic learning resources

- Institute of the Language of the Quran - Free Video lectures on basic and advanced Classical Arabic grammar

- Arabic Grammar Checking

- Arabic Intelligent tutoring system

- Classical Arabic Morphology

- Classical Arabic Grammar

- Classical Arabic Blog

- Arabic grammar online

- Online Classical Arabic Reader

- Classical Arabic Grammar Documentation – Visualization of Classical Quranic Grammar (iʻrāb)

- Die Wissenschaft des Tadschwīd

- EssentialIlm – Free Video Lessons on Arabic

- Quranic Arabic, Classical Arabic and MSA Different types of Arabic at Arabic-Studio.com

- Pattern-and-root inflectional morphology: the Arabic broken plural