Legislative Assembly of Queensland

| Legislative Assembly | |

|---|---|

| |

| Type | |

| Type | |

| History | |

| Founded | 1859 |

| Leadership | |

| Structure | |

| Seats | 89 |

| |

Political groups |

Government (42) Opposition (42) |

| Elections | |

Last election | 31 January 2015 |

Next election | 2018 or earlier |

| Meeting place | |

|

| |

|

Legislative Assembly Chamber, Parliament House, Brisbane, Queensland, Australia | |

| Website | |

| www.parliament.qld.gov.au | |

The Legislative Assembly of Queensland is the sole chamber of the unicameral Parliament of Queensland. Elections are held approximately once every three years. Voting is by the optional preferential voting form of the alternative vote system. The Assembly has 89 members, who have used the letters MP after their names since 2000 (previously they were styled MLAs).

There is approximately the same population in each electorate; however, that has not always been the case (see Queensland's gerrymander). The Assembly first sat in May 1860 and produced Australia's first Hansard in April 1864.

Following the outcome of the 2015 election, successful amendments to the electoral act in early 2016 include: adding an additional four parliamentary seats from 89 to 93, changing from optional preferential voting to full-preferential voting, and moving from unfixed three-year terms to fixed four-year terms.[1]

History

| Legislative Assembly of Queensland[2] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Election / Assembly number |

ALP | Conservatives NAT/LIB |

ONP | Other | Total |

20 / 11 |

|||||

15 / 8 |

|||||

16 / 8 |

|||||

41 / 8 |

|||||

49 / 10 |

|||||

27 / 8 |

|||||

26 / 9 |

|||||

29 / 14 |

|||||

23 / 9 |

|||||

12 / 3 |

|||||

15 / 5 |

|||||

17 / 8 |

|||||

1860–1948

Initially, the Legislative Assembly was the lower house of a typical Westminster-style bicameral parliament. The upper house was the Legislative Council, its members appointed for life by the government of the day. The first sitting, in May 1860, was held in the old converted convict barracks in Queen Street.[3] It consisted of 26 members from 16 electorates, nearly half of whom were pastoralists or squatters. Early sessions dealt with issues of land, labour, railways, public works, immigration, education and gold discoveries.[3]

In April 1864, Australia's first Hansard was produced. It was the second Hansard to be made in the Commonwealth, after Nova Scotia in 1855.[3] That year also saw member numbers increased to 32, and by 1868—as more redistributions occurred—the number grew to 42. Members were not paid until 1886, effectively excluding the working class from state politics.[3]

The Assembly was elected under the 'first-past-the-post' (plurality) system 1860 to 1892. From then until 1942 an unusual form of preferential voting called the 'contingent vote' was used. This was done by a conservative government to prevent the Labor Party from gaining seats.[4]

In 1942 the plurality system was reintroduced until it was replaced in 1962 by the 'full preferential' form of the Alternative Vote. This was done by the Labor Party, which saw a decline in votes in the 1940s, to divide the opposition.[4] In 1992, this was changed to the optional preferential system currently used.[4]

After 1912, electorates elected only a single member to the Assembly.[4] In 1922, the Legislative Council was abolished, with the help of members known as the "suicide squad", who were specially appointed to vote the chamber out of existence. This left Queensland with a unicameral parliament—currently the only Australian state with this arrangement.

Queensland's "gerrymander" 1948–1989

From 1948 until the reforms following the end of the Bjelke-Petersen era, Queensland used an electoral zoning system that was tweaked by the government of the day to maximise its own voter support at the expense of the opposition. It has been called a form of gerrymander, however it is more accurately referred to as an electoral malapportionment. In a classic gerrymander, electoral boundaries are drawn to take advantage of known pockets of supporters and to isolate areas of opposition voters so as to maximise the number of seats for the government for a given number of votes and to cause opposition support to be "wasted" by concentrating their supporters in relatively fewer electorates.

The Queensland "gerrymander", first introduced by the Australian Labor Party (ALP) government of Ned Hanlon in 1949 used a series of electoral zones based on their distance from Brisbane.

Initially Queensland was divided into three zones—the metropolitan zone (Brisbane), the provincial cities zone (which also included rural areas around provincial cities) and the rural zone. While the number of electors in each seat in a zone was roughly equal, there was considerable variation in the number of electors between zones. Thus an electorate in the remote zone might have as few as 5,000 electors, while a seat in the metropolitan zone might have as many as 25,000. Using this system the Labor government was able to maximise its vote, particularly in its power base of the provincial city zone.

With the split in the party in the late 1950s the ALP lost office and a conservative Coalition government led by the Country Party (later National Party of Australia), came to power, which, as discussed above, initially modified the voting system to introduce preferential voting, to take advantage of Labor's split. It also separated the provincial cities from their hinterlands. The hinterlands were added to the rural zone, where new Country Party seats were created. Subsequently as the divisions in the ALP abated in the early 1970s, and tensions in the conservative coalition grew, (thus reducing the advantage to be gained by the use of preferential voting), the conservative government modified the zoning system to add a fourth zone—a remote zone, comprising seats with even fewer electors. Thus the conservative government was able to isolate Labor support in provincial cities and maximise its own rural power base. On average, the Country Party needed only 7,000 votes to win a seat, compared with 12,800 for a typical Labor seat.

The entrenchment of a conservative government was also caused by socio-economic and demographic changes associated with mechanisation of farms and urbanisation which led to a drift of working class population from rural and remote electorates to the cities.

By the late 1980s the decline in the political fortunes of the National Party, together with rapid growth in south east Queensland meant that the zonal system was no longer able to guarantee a conservative victory.

In addition, in 1988 the Federal Labor Government held four constitutional referendums—one of which was for the adoption of fair electoral systems around Australia. Although the referendum did not succeed, it heightened public awareness of the issue. A large public interest non-partisan organisation, the Citizens for Democracy, lobbied extensively the Liberal and Labor parties to abolish the gerrymander and to make it a major issue in the lead up to the landmark 1989 Queensland election.

1989–present

In 1989 Labor won government, promising to implement the recommendations of the Fitzgerald Inquiry into police corruption, including the establishment of an Electoral and Administrative Reform Commission (EARC). EARC recommended the abolition of the zonal system in favour of a "modified one vote, one value" system. Under this proposal, subsequently adopted, most electorates consisted of approximately the same number of electors, but with a greater tolerance for fewer electors allowed in a limited number of remote electorates. This plan is still in use today, with 40 seats contested in Brisbane and 49 in the rest of the state.

The youngest person ever elected to Queensland's Legislative Assembly was Lawrence Springborg, former Minister for Natural Resources and Leader of the Opposition.[5] In 1989, he entered parliament aged 21.

Parliament House

The Queensland Legislative Assembly sits in Parliament House in the Brisbane central business district. The building was completed in 1891. The lower house chamber is decorated dark green in the traditional Westminster style. The chamber once featured central tables which divided two rows of elevated benches on each side. The room is now configured in a U-shape away from the Speaker's chair with three rows of benches that have their own desks and microphones.[6]

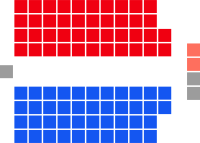

Distribution of seats

As of 7 March 2016, the distribution of seats is:

| Party | Seats | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 | Current Assembly (Total 89 Seats) | ||

| Labor | 42 | | |

| Liberal National | 42 | | |

| Katter's Australian | 2 | | |

| Independent | 3 | | |

- 45 votes as a majority are required to pass legislation. All three independents support the Labor government on confidence and supply.

See also

- Members of the Queensland Legislative Assembly by dates

- Category:Members of the Queensland Legislative Assembly by names

- Parliaments of the Australian states and territories

- Politics of Queensland

References

- ↑ "Electoral Law Ructions in the Queensland Parliament". Antony Green's Election Blog. 21 April 2016. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ↑ Queensland Parliamentary Record. "Table 1. Precis of results of Queensland state elections 1932 to 2009" (PDF). Retrieved 5 April 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Armstrong, Lyn (1997), "'A somewhat rash experiment':Queensland Parliament as a microcosm of society", in Shaw, Barry, Brisbane:Corridors of Power, Papers, 15, Brisbane: Brisbane History Group Inc, pp. 54—55, ISBN 0958646910

- 1 2 3 4 Wanna, John (2003). "Queensland". In Moon, Campbell; Sharman, Jeremy. Australian Politics and Government: The Commonwealth, the States and Territories. Cambridge, United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press. pp. 93—94. ISBN 0521825075. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ↑ "Bligh calls early Queensland election". The Courier-Mail. News Limited. 22 February 2009. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

- ↑ Wanna, John; Tracy Arklay (2010). The Ayes Have it: The History of Queensland Parliament 1957—1989. Canberra: ANU E Press. p. 9. ISBN 9781921666308. Retrieved 15 November 2011.

External links

- Queensland Parliament official website