Quantum pseudo-telepathy

Quantum pseudo-telepathy is a phenomenon in quantum game theory resulting in anomalously high success rates in coordination games between separated players. These high success rates would require communication between the players in a purely classical (non-quantum) world; however, the game is set up such that during the game, communication is physically impossible. This means that for quantum pseudo-telepathy to occur, prior to the game the participants need to share a physical system in an entangled quantum state, and during the game have to execute measurements on this entangled state as part of their game strategy. Games in which the application of such a quantum strategy leads to pseudo-telepathy are also referred to as quantum non-locality games.

In their 1999 paper,[1] Gilles Brassard, Richard Cleve and Alain Tapp demonstrated that winning quantum strategies can exist in simple games for which in the absence of quantum entanglement a winning strategy can result only if the participants were allowed to communicate. The term quantum pseudo-telepathy was later introduced[2] for this phenomenon. The prefix 'pseudo' is appropriate, as the quantum non-locality effects that are at the heart of the phenomenon do not allow any transfer of information, but rather eliminate the need to exchange information between the players for achieving a mutual win in the game.

The phenomenon of quantum pseudo-telepathy is mostly used as a powerful and explicit thought experiment of the non-local characteristics of quantum mechanics. Yet, the effect is real and subject to experimental verification, as demonstrated by the experimental confirmation of the violation of the Bell inequalities.

The Mermin-Peres magic square game

An example of quantum pseudo-telepathy can be observed in the following two-player coordination game in which, in each round, one participant fills one row and the other fills one column of a 3x3 table with plus and minus signs.

The two players Alice and Bob are separated so that no communication between them is possible. In each round of the game, Alice is told which row is selected for her to fill in, and Bob is told which column is selected for him. Alice is not told which column Bob must fill in, and Bob is not told which row Alice must fill in. One may assume that the selection is done by chance or by a hostile party.

Alice and Bob place their numbers according to the following rules. Alice must fill in her row such that there is an even number of minus signs in that row. Bob must fill in his column such that there is an odd number of minus signs in that column.

If Alice and Bob place the same sign in the cell shared by their row and column, they win the round. If they place opposite signs, they lose the round. After the round is complete, the game board is cleared. They may play repeatedly, and they try to win as often as possible.

In the classic (non-quantum) form of the game, Alice and Bob are permitted to agree on a game playbook in advance. The only rule is that they cannot communicate after they are separated.

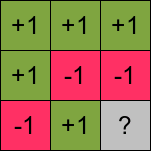

It is easy to see that any prior agreement between Alice and Bob on the use of specific tables filled with + and – signs is not going to enable them to win all the time. The reason is that a perfectly consistent table does not exist: it would be self-contradictory, with the sum of the minus signs in the table being even based on row sums, and being odd when using column sums. As a further illustration, if they use the partial table shown in the diagram (supplemented by a -1 for Alice and a +1 for Bob in the missing square) and the challenge rows and columns are selected at random, they will win 8/9 of the time. No classical strategy without communication can beat this victory rate (with random row and column selection).

The winning strategy

So, how can Alice and Bob succeed in winning all the time?

Although they are separated "so that no communication between them is possible", coordination can be provided through two pairs of particles with entangled states, in which one particle of each pair is held by Alice and the other by Bob. Once Alice and Bob learn which column and row they must fill, each uses that information to select which measurements they should make to their particles. The result of the measurements will appear to each of them to be random (and the observed probability distribution will be independent of the measurement performed by the other party), so no real "communication" takes place. But there is a coordinating effect they can take advantage of. If each of them follows the advice of their measurements, they are sure to win. Moreover, it is not possible for the referee to "separate" them in any way to keep this coordination from taking place. They can be light years apart from one another, and the entangled particles will still provide that critical hint.

Each round of play uses up one entangled state. Playing N rounds requires that N entangled states (2N independent Bell pairs, see below) be shared in advance. This is because each round needs 2-bits of information to be measured (the third entry is determined by the first two, so measuring it isn't necessary), which destroys the entanglement. There is no way to reuse old measurements from earlier games.

The trick is for Alice and Bob to share an entangled quantum state and to use specific measurements on their components of the entangled state to derive the table entries. A suitable correlated state consists of an entangled pair of Bell states:

here and are eigenstates of the Pauli operator Sz with eigenvalues +1 and −1, respectively, whilst the subscripts a, b, c, and d identify the components of each Bell state, with a and c going to Alice, and b and d going to Bob. Note that all four particles are entangled: the above is a single state, and not two distinct, separable Bell states. This four-way entanglement is key to the winning measurement process.

Observables for these components can be written as products of the Pauli spin matrices:

Products of these Pauli spin operators can be used to fill the 3x3 table such that each row and each column contains a mutually commuting set of observables with eigenvalues +1 and −1, and with the product of the obervables in each row being the identity operator, and the product of observables in each column equating to minus the identity operator. This so-called Mermin–Peres magic square[3] is shown in below table.

Effectively, while it is not possible to construct a 3x3 table with entries +1 and −1 such that the product of the elements in each row equals +1 and the product of elements in each column equals −1, it is possible to do so with the richer algebraic structure based on spin matrices.

The play proceeds by having each player make three measurements on one (shared) entangled state per round of play. A different measurement must be made to obtain an entry for each box; the measurement to be made is indicated in the table above. It is possible to consistently make all three measurements on one state: that is because the three needed operators all commute. Thus, each player obtains three values. As long as the table above is used, the resulting measurements are guaranteed to always multiply out to +1 for Alice, and -1 for Bob, thus winning the round. Of course, each new round requires a new entangled state, as different rows and columns are not compatible with each other.

Current research

It has been demonstrated[4] that the above described game is the simplest two-player game in which quantum pseudo-telepathy (for which there is a quantum strategy with a guaranteed win) can occur. Other games in which quantum pseudo-telepathy occurs have been studied, including larger magic square games,[5] graph colouring games[6] giving rise to the notion of quantum chromatic number,[7] and multiplayer games involving more than two participants.[8] Recent studies tackle the question of the robustness of the effect against noise due to imperfect measurements on the coherent quantum state.[9] Recent work has shown an exponential enhancement in the communication cost of nonlinear distributed computation, due to entanglement, when the communication channel itself is restricted to be linear.[10]

See also

- GHZ state - an entangled 3-particle state.

- EPR paradox

- Kochen-Specker theorem

- Quantum information science

- Qubit

- Tsirelson's bound

- Wheeler–Feynman absorber theory

Notes

- ↑ Gilles Brassard, Richard Cleve, Alain Tapp, "The cost of exactly simulating quantum entanglement with classical communication" (1999).

- ↑ Gilles Brassard, Anne Broadbent, Alain Tapp, "Multi-Party Pseudo-Telepathy" (2003).

- ↑ Here we use the table as defined in: P.K. Aravind, "Quantum mysteries revisited again", American Journal of Physics. 72, 1303-7 (2004).

- ↑ Nicolas Gisin, Andre Allan Methot, Valerio Scarani, "Pseudo-telepathy: input cardinality and Bell-type inequalities" (2006).

- ↑ Samir Kunkri, Guruprasad Kar, Sibasish Ghosh, Anirban Roy, "Winning strategies for pseudo-telepathy games using single non-local box" (2006).

- ↑ David Avis, Jun Hasegawa, Yosuke Kikuchi and Yuuya Sasaki, "A quantum protocol to win the graph colouring game on all Hadamard graphs" (2005).

- ↑ Peter J. Cameron, Ashley Montanaro, Michael W. Newman, Simone Severini, Andreas Winter, "On the quantum chromatic number of a graph" Electronic Journal of Combinatorics 14(1), 2007.

- ↑ Gilles Brassard, Anne Broadbent, Alain Tapp, "Recasting Mermin's multi-player game into the framework of pseudo-telepathy" (2004).

- ↑ P. Gawron, J.A. Miszczak, J. Sladkowski, "Noise Effects in Quantum Magic Squares Game", International Journal of Quantum Information, Vol. 6, No. 1 (2008), pp. 667–673.

- ↑ A. Marblestone and M. Devoret, "Exponential Quantum Enhancement for Distributed Addition with Local Nonlinearity", Quantum Information Processing, Vol. 9, No.1 (2010)