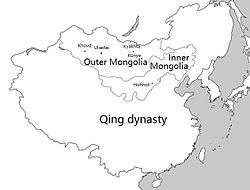

Qing dynasty in Inner Asia

The Qing dynasty in Inner Asia was the expansion of the Qing dynasty's realm in Inner Asia in the 17th and the 18th century AD, including both Inner and Outer Mongolia, Manchuria, Tibet, Qinghai and Xinjiang. Wars were fought primarily against the Northern Yuan dynasty (before 1636) and the Dzungar Khanate (1687–1758). Even before the conquest of China proper (see Qing conquest of the Ming), the Manchus had controlled Manchuria (modern Northeast China as well as Outer Manchuria) and Inner Mongolia, with the latter being previously controlled by the Mongols under Ligdan Khan. After suppressing the Revolt of the Three Feudatories and the conquest of Taiwan as well as ending the Sino-Russian border conflicts in the 1680s, the Dzungar–Qing War broken out. This eventually led to Qing conquests of Outer Mongolia, Tibet, Qinghai and Xinjiang. All of them became part of the Qing Empire and were garrisoned by Qing forces, but they were governed through several different types of administrative structure[1] and also retained many of their existing institutions. Furthermore, they were not governed as regular provinces (until Xinjiang and Manchuria were turned into provinces in late Qing), but instead were supervised by the Lifan Yuan, a Qing government agency that oversaw the empire's frontier regions.

Manchuria

The Qing dynasty was founded not by Han Chinese, who form the majority of the Chinese population, but by a sedentary farming people known as the Jurchen, a Tungusic people who lived around the region now comprising the Chinese provinces of Jilin and Heilongjiang.[2] What was to become the Manchu state was founded by Nurhaci, the chieftain of a minor Jurchen tribe – the Aisin Gioro – in Jianzhou in the early 17th century. Originally a vassal of the Ming emperors, Nurhachi embarked on an intertribal feud in 1582 that escalated into a campaign to unify the nearby tribes. By 1616, he had sufficiently consolidated Jianzhou so as to be able to proclaim himself Khan of the Great Jin in reference to the previous Jurchen dynasty.[3] Two years later, Nurhachi announced the "Seven Grievances" and openly renounced the sovereignty of Ming overlordship in order to complete the unification of those Jurchen tribes still allied with the Ming emperor. After a series of successful battles against both the Ming and various tribes in Outer Manchuria, he and his son Hong Taiji eventually controlled the whole of Manchuria. However, during the Qing conquest of the Ming in the later decades, the Tsardom of Russia tried to gain the land north of the Amur River. This was eventually rebutted by the Qing in the 1680s, resulting in the Treaty of Nerchinsk in 1689 which gave the land to China. During the mid-19th century, however, Outer Manchuria was eventually lost to the Russians during the Amur Acquisition by the Russian Empire.

Han Chinese were banned from settling in this region but the rule was openly violated and Han Chinese became a majority in urban areas by the early 19th century.

In 1668 during the reign of the Kangxi Emperor, the Qing government further decreed a prohibition of non-Eight Banner people getting into this area of their origin.

However Qing rule saw an massively increasing amount of Han Chinese both illegally and legally streaming into Manchuria and settling down to cultivate land as Manchu landlords desired Han Chinese peasants to rent on their land and grow grain, most Han Chinese migrants were not evicted as they went over the Great Wall and Willow Palisade, during the eighteenth century Han Chinese farmed 500,000 hectares of privately owned land in Manchuria and 203,583 hectares of lands which were part of coutrier stations, noble estates, and Banner lands, in garrisons and towns in Manchuria Han Chinese made up 80% of the population.[4]

Han Chinese farmers were resettled from north China by the Qing to the area along the Liao River in order to restore the land to cultivation.[5] Wasteland was reclaimed by Han Chinese squatters in addition to other Han who rented land from Manchu landlords.[6] Despite officially prohibiting Han Chinese settlement on the Manchu and Mongol lands, by the 18th century the Qing decided to settle Han refugees from northern China who were suffering from famine, floods, and drought into Manchuria and Inner Mongolia so that Han Chinese farmed 500,000 hectares in Manchuria and tens of thousands of hectares in Inner Mongolia by the 1780s.[7] Qianlong allowed Han Chinese peasants suffering from drought to move into Manchuria despite him issuing edicts in favor of banning them from 1740-1776.[8] Chinese tenant farmers rented or even claimed title to land from the "imperial estates" and Manchu Bannerlands in the area.[9] Besides moving into the Liao area in southern Manchuria, the path linking Jinzhou, Fengtian, Tieling, Changchun, Hulun, and Ningguta was settled by Han Chinese during the Qianlong Emperor's reign, and Han Chinese were the majority in urban areas of Manchuria by 1800.[10] To increase the Imperial Treasury's revenue, the Qing sold formerly Manchu only lands along the Sungari to Han Chinese at the beginning of the Daoguang Emperor's reign, and Han Chinese filled up most of Manchuria's towns by the 1840s according to Abbe Huc.[11]

Inner and Outer Mongolia

During the course of the 17th and 18th centuries, most regions inhabited by ethnic Mongols, notably Outer and Inner Mongolia became part of the Qing Empire. Even before the dynasty began to take control of China proper in 1644, the escapades of Ligden Khan had driven a number of Mongol tribes to ally with the Manchu state. The Manchus conquered a Mongol tribe in the process of war against the Ming. Nurhaci's early relations with the Mongols tribes was mainly an alliance.[12][13] With Ligden's defeat and death his son Ejei Khan had to submit to the Manchus, and most of what is now Inner Mongolia was incorpoation to the Qing. The three khans of Khalkha in Outer Mongolia had established close ties with the Qing dynasty since the reign of Hong Taiji, but had remained effectively self-governing. While Qing rulers had attempted to achieve control over this region, the Oirats to the west of Khalkha under the leadership of Galdan were also actively making such attempts. After the end of the war against the Three Feudatories, the Kangxi Emperor was able to turn his attentions to this problem and tried diplomatic negotiations. But Galdan ended up with attacking the Khalkha lands, and Kangxi's responded by personally leading Eight Banner contingents with heavy guns into the field against Galdan's forces, eventually defeating the latter. In the mean time Kangxi organized a congress of the rulers of Khalkha and Inner Mongolia in Duolun in 1691, at which the Khalkha khans formally declared allegiance to him. The war against Galdan essentially brought the Khalkhas to the empire, and the three khans of the Khalkha were formally inducted into the inner circles of the Qing aristocracy by 1694. Thus, by the end of the 17th century the Qing dynasty had put both Inner and Outer Mongolia under its control.

Han Chinese were officially forbidden to settle in Inner and Outer Mongolia. Mongols were forbidden from crossing into the Han Chinese 18 provinces (neidi) without permission and were given punishments if they did. Mongols were forbidden from crossing into another Mongol leagues. Han Chinese settlers violated the rule and crossed into and settled in Inner Mongolia.

Despite officially prohibiting Han Chinese settlement on the Manchu and Mongol lands, by the 18th century the Qing decided to settle Han refugees from northern China who were suffering from famine, floods, and drought into Manchuria and Inner Mongolia so that Han Chinese farmed 500,000 hectares in Manchuria and tens of thousands of hectares in Inner Mongolia by the 1780s.[14]

Ordinary Mongols were not allowed to travel outside their own leagues. Mongols were forbidden by the Qing from crossing the borders of their banners, even into other Mongol Banners and from crossing into neidi (the Han Chinese 18 provinces) and were given serious punishments if they did in order to keep the Mongols divided against each other to benefit the Qing.[15]

During the eighteenth century, growing numbers of Han Chinese settlers had illegally begun to move into the Inner Mongolian steppe. By 1791 there had been so many Han Chinese settlers in the Front Gorlos Banner that the jasak had petitioned the Qing government to legalize the status of the peasants who had already settled there.[16]

Tibet

Güshi Khan, founder of the Khoshut Khanate overthrew the prince of Tsang and made the 5th Dalai Lama the highest spiritual and political authority in Tibet,[17] establishing the regime known as Ganden Phodrang in 1642. The Dzungar Khanate under Tsewang Rabtan invaded Tibet in 1717, deposed the pretender to the position of Dalai Lama of Lha-bzang Khan, the last ruler of the Khoshut Khanate, and killed Lha-bzang Khan and his entire family. In response, an expedition sent by the Kangxi Emperor of the Qing dynasty, together with Tibetan forces under Polhané Sönam Topgyé of Tsang and Kangchennas (also spelled Gangchenney), the governor of Western Tibet,[18][19] expelled the Dzungars from Tibet in 1720 as patrons of the Khoshut and liberators of Tibet from the Dzungars. This began the Qing administrative rule of Tibet, which lasted until the fall of the Qing dynasty in 1912, although the region retained a degree of political autonomy under the Dalai Lamas. The Qing emperors appointed imperial residents known as the Ambans to Tibet, who commanded over 2,000 troops stationed in Lhasa and reported to the Lifan Yuan.

The Qing stationed both Manchu Bannermen and Han Chinese Green Standard Army soldiers in Tibet. A community descended from Han Chinese soldiers and officials grew in Lhasa.

At multiple places such as Lhasa, Batang, Dartsendo, Lhari, Chamdo, and Litang, Green Standard troops were garrisoned throughout the Dzungar war.[20] Green Standard Army troops and Manchu Bannermen were both part of the Qing force who fought in Tibet in the war against the Dzungars.[21] It was said that the Sichuan commander Yue Zhongqi (a descendant of Yue Fei) entered Lhasa first when the 2,000 Green Standard soldiers and 1,000 Manchu soldiers of the "Sichuan route" seized Lhasa.[22] According to Mark C. Elliott, after 1728 the Qing used Green Standard Army troops to man the garrison in Lhasa rather than Bannermen.[23] According to Evelyn S. Rawski both Green Standard Army and Bannermen made up the Qing garrison in Tibet.[24] According to Sabine Dabringhaus, Green Standard Chinese soldiers numbering more than 1,300 were stationed by the Qing in Tibet to support the 3,000 strong Tibetan army.[25]

In the mid 19th century, arriving with an Amban, a community of Chinese troops from Sichuan who married Tibetan women settled down in the Lubu neighborhood of Lhasa, where their descendants established a community and assimilated into Tibetan culture.[26] Hebalin was the location of where Chinese Muslim troops and their offspring lived, while Lubu was the place where Han Chinese troops and their offspring lived.[27]

Qinghai

From 1640 to 1724, a big part of the area that is now Qinghai was under the control of the Khoshut Mongols, who nominally acknowledged their allegiance to the Qing dynasty. However, after the Dzungar invasion which ended the Khoshut Khanate in Tibet and the subsequent Qing conquest of Tibet in 1720, the Upper Mongols led by the ruling prince Lubsan Danzan in Qinghai revolted against the Qing under the Yongzheng Emperor in 1723. Lubsan Danzan also made contact with the Dzungar Khanate in Xinjiang before the revolt. 200,000 Tibetans and Mongols in Qinghai attacked Xining, although Central Tibet did not support the rebellion. In fact, Polhanas based in Central Tibet blocked the rebels' retreat from Qing retaliation.[28] Chinese commanders such as Nian Gengyao were sent to suppress the revolt. Eventually the rebellion was brutally suppressed, which marked the onset of direct Qing rule in Qinghai. Lubsan Danzan fled to the Dzungar Khanate and was later captured by the Manchus in 1755 during the Qianlong Emperor's campaigns to Xinjiang. Most of present-day Qinghai was put under the control of the Minister of Xining Handling Affairs (Chinese: 西寧辦事大臣, also known as the Xining Amban) located in Xining in 1724 by the Qing, although Xining itself was governed by the Gansu province during the period. This lasted until the end of the Qing dynasty.

Xinjiang

The area called Dzungaria in present-day Xinjiang was the base of the Dzungar Khanate. The Qing dynasty gained control over eastern Xinjiang as a result of a long struggle with the Dzungars that began in the 17th century. In 1755, with the help of the Oirat nobel Amursana, the Qing attacked Ghulja and captured the Dzungar khan. After Amursana's request to be declared Dzungar khan went unanswered, he led a revolt against the Qing. Over the next two years, Qing armies destroyed the remnants of the Dzungar khanate. The native Dzungar Oirat Mongols suffered heavily from the brutal campaigns and a simultaneous smallpox epidemic. After the campaigns against the Dzungars in 1758, two Altishahr nobles, the Khoja brothers Burhān al-Dīn and Khwāja-i Jahān, started a revolt against the Qing Empire. However, it was crushed by the Qing forces by 1759, which marked the beginning of whole Xinjiang under Qing rule. The Kumul Khanate was incorporated into the Qing Empire as a semi-autonomous vassal within Xinjiang. The Qianlong Emperor compared his achievements with that of the Han and Tang ventures into Central Asia.[29] The Qing dynasty put the entire Xinjiang under the rule of the General of Ili who established a center of government at the fort of Huiyuan (the so-called "Manchu Kuldja", or Yili), 30 km (19 mi) west of Ghulja (Yining). This brought the previously two separate regions, the Dzungaria in the north and the Tarim Basin (Altishahr) in the south under his rule as Xinjiang.[30]

The Qing implemented two different policies for Dzungaria and the Tarim Basin. Han Chinese were encouraged by the Qing to permanently settle and colonize Dzungaria while permanent Han settlers were banned from the Tarim with only Han merchants and Han Green Standard Army soldiers stationed in rotating garrisons allowed in the Tarim Basin. The ban was lifted in the 1820s after the invasion of Jahangir Khoja and Han Chinese were allowed to permanently settle in the Tarim. During the weakening of the Qing dynasty in the mid-19th century, both Chinese Muslims (Hui) and Uyghurs rebelled in Xinjiang cities, following on-going Chinese Muslim Rebellions in Gansu and Shaanxi provinces further east. In 1865, Yaqub Beg, a warlord from the neighbouring Khanate of Kokand, entered Xinjiang via Kashgar and conquered nearly all of Xinjiang over the next six years.[31] At the Battle of Ürümqi (1870) Yaqub Beg's Turkic forces, allied with a Han Chinese militia, attacked and besieged Chinese Muslim forces in Ürümqi. In 1871, the Russian Empire took advantage of the chaotic situation and seized the rich Ili River valley, including Gulja. At the end of this period, forces loyal to the Qing held onto only a few strongholds, including Tacheng. Yaqub Beg's rule lasted until the Qing general Zuo Zongtang (also known as General Tso) reconquered the region between 1876 and 1878. In 1881, the Qing recovered the Gulja region through diplomatic negotiations, via the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1881). The Qing dynasty established Xinjiang ("new frontier") as a province in 1884, formally applying to it the political systems of the China proper and dropping the old names of Zhunbu (準部, Dzungar region) and Huijiang, "Muslimland."[32][33]

Identifying the Qing state with China

The Qing identified their state as Zhongguo ("中國", lit. "central state", the term for "China" in modern Chinese), and referred to it as "Dulimbai Gurun" in Manchu and "China" in English. The Qing equated the lands of the Qing state (including Manchuria, Xinjiang, Mongolia, and other areas under Qing control) as "China" in both the Chinese and Manchu languages, defining China as a multi-ethnic state. After the Qing conquered Xinjiang in 1759, they proclaimed that the new land was now absorbed into "China" (Dulimbai Gurun) in a Manchu language memorial.[34][35][36] The Qianlong Emperor explicitly commemorated the Qing conquest of the Dzungars as having added new territory in Xinjiang to Zhongguo, defining China as a multi-ethnic state, rejecting the idea that China only meant Han areas in "China proper", meaning that according to the Qing, both Han and non-Han peoples were part of China (Zhongguo). Similarly, the "Chinese language" (Dulimbai gurun i bithe) referred to Chinese, Manchu, and Mongol languages, while the term "Chinese people" (中國之人 Zhongguo zhi ren; Manchu: Dulimbai gurun i niyalma) referred to all Han, Manchus, and Mongol subjects of the Qing. The Qing expounded on their ideology that they were bringing together the "outer" non-Han Chinese like the Inner Mongols, Eastern Mongols, Oirat Mongols, and Tibetans together with the "inner" Han Chinese, into "one family" united in the Qing state, showing that the diverse subjects of the Qing were all part of one family, the Qing used the phrase "Zhong Wai Yi Jia" (中外一家) or "Nei Wai Yi Jia" (內外一家, "interior and exterior as one family"), to convey this idea of "unification" of the different peoples.[37] The Qianlong Emperor rejected earlier ideas that only Han Chinese could be subjects of China and only Han land could be considered as part of China, saying in 1755 that "There exists a view of China (zhongxia), according to which non-Han people cannot become China's subjects and their land cannot be integrated into the territory of China. This does not represent our dynasty's understanding of China, but is instead that of the earlier Han, Tang, Song, and Ming dynasties."[38] The term "Zhongguo" or "China" was also used extensively to refer to the Qing in foreign communications and treaties with other states. It appeared in a formal Qing government document for the first time in the 1689 Treaty of Nerchinsk signed with the Russians. Nevertheless, the Qing implemented different ways of legitimization for different peoples in the Qing Empire, such as acting as Khan to the Mongols instead of as Emperor of China to these non-Han subjects.

See also

- Lifan Yuan

- Amban

- Dzungar–Qing War

- Ten Great Campaigns

- New Qing History

- Tang dynasty in Inner Asia

- Yuan dynasty in Inner Asia

References

- ↑ The Cambridge History of China: Volume 10, Part 1, by John K. Fairbank, p37

- ↑ Ebrey (2010), p. 220.

- ↑ Ebrey (2010), pp. 220–224.

- ↑ Richards 2003, p. 141.

- ↑ Reardon-Anderson 2000, p. 504.

- ↑ Reardon-Anderson 2000, p. 505.

- ↑ Reardon-Anderson 2000, p. 506.

- ↑ Scharping 1998, p. 18.

- ↑ Reardon-Anderson 2000, p. 507.

- ↑ Reardon-Anderson 2000, p. 508.

- ↑ Reardon-Anderson 2000, p. 509.

- ↑ Marriage and inequality in Chinese society By Rubie Sharon Watson, Patricia Buckley Ebrey, p.177

- ↑ Tumen jalafun jecen akū: Manchu studies in honour of Giovanni Stary By Giovanni Stary, Alessandra Pozzi, Juha Antero Janhunen, Michael Weiers

- ↑ Reardon-Anderson, James (Oct 2000). "Land Use and Society in Manchuria and Inner Mongolia during the Qing Dynasty". Environmental History. Forest History Society and American Society for Environmental History. 5 (No. 4): 506. JSTOR 3985584.

- ↑ Bulag 2012, p. 41.

- ↑ The Cambridge History of China. 10. Cambridge University Press. 1978. p. 356.

- ↑ René Grousset, The Empire of the Steppes, New Brunswick 1970, p. 522

- ↑ Mullin 2001, p. 290

- ↑ Smith 1997, p. 125

- ↑ Wang 2011, p. 30.

- ↑ Dai 2009, p. 81.

- ↑ Dai 2009, pp. 81-2.

- ↑ Elliott 2001, p. 412.

- ↑ Rawski 1998, p. 251.

- ↑ Dabringhaus 2014, p. 123.

- ↑ Yeh 2009, p. 60.

- ↑ Yeh 2013, p. 283.

- ↑ Smith 1997, pp. 125-6

- ↑ Millward 1998, p. 25.

- ↑ Newby 2005, p. 1.

- ↑ Yakub Beg (Pamiri adventurer). Britannica Online Encyclopedia.

- ↑ Tyler (2003), p. 61.

- ↑ 从“斌静案”看清代驻疆官员与新疆的稳定 Archived April 20, 2016, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Dunnell 2004, p. 77.

- ↑ Dunnell 2004, p. 83.

- ↑ Elliott 2001, p. 503.

- ↑ Dunnell 2004, pp. 76-77.

- ↑ Zhao 2006, p. 4.