Ptolemy I Soter

| Ptolemy I Soter I Founder of the Ptolemaic Kingdom | |

|---|---|

|

Bust of Ptolemy I in the Louvre Museum | |

| Pharaoh | |

| Consort |

Artakama Thaïs Eurydice Berenice I |

| Children |

With Berenice I: Ptolemy II Philadelphus Arsinoe II Philotera With Thaïs: Lagus Leontiscus Eirene With Eurydice: Ptolemy Keraunos Meleager Argaeus Lysandra Ptolemais |

| Father | Lagus |

| Mother | Arsinoe of Macedonia |

| Born | c. 367 BC, Macedon |

| Died | 283/2 BC (aged 84); Alexandria, Egypt |

Ptolemy I Soter I (Ancient Greek: Πτολεμαῖος Σωτήρ, Ptolemaĩos Sōtḗr, i.e. Ptolemy (pronounced /ˈtɒləmi/) the Savior), also known as Ptolemy Lagides[1] (c. 367 BC – 283/2 BC), was a Macedonian[2][3][4][5][6] general under Alexander the Great, one of the three Diadochi who succeeded to his empire. Ptolemy became ruler of Egypt (323–283/2 BC) and founded a dynasty which ruled it for the next three centuries, turning Egypt into a Hellenistic kingdom and Alexandria into a center of Greek culture. He assimilated some aspects of Egyptian culture, however, assuming the traditional title pharaoh in 305/4 BC. The use of the title of pharaoh was often situational, pharaoh was used for an Egyptian audience, and Basileus for a Greek audience, as exemplified by Egyptian coinage.

Like all Macedonian nobles, Ptolemy I Soter claimed descent from Heracles, the mythical founder of the Argead dynasty that ruled Macedon. Ptolemy's mother was Arsinoe of Macedon, and, while his father is unknown, ancient sources variously describe him either as the son of Lagus, a Macedonian nobleman, or as an illegitimate son of Philip II of Macedon (which, if true, would have made Ptolemy the half-brother of Alexander), but it is possible that this is a later myth fabricated to glorify the Ptolemaic dynasty. Ptolemy was one of Alexander's most trusted generals, and was among the seven somatophylakes (bodyguards) attached to his person. He was a few years older than Alexander and had been his intimate friend since childhood.

He was succeeded by his son Ptolemy II Philadelphus.

Early career

Ptolemy served with Alexander from his first campaigns, and played a principal part in the later campaigns in Afghanistan and India. He participated in the Battle of Issus and accompanied Alexander during his journey to the Oracle in the Siwa Oasis where he was proclaimed a son of Zeus.[7] Ptolemy had his first independent command during the campaign against the rebel Bessus whom Ptolemy captured and handed over to Alexander for execution.[8] During Alexander's campaign in the Indian subcontinent Ptolemy was in command of the advance guard at the siege of Aornos and fought at the Battle of the Hydaspes River.

Successor of Alexander

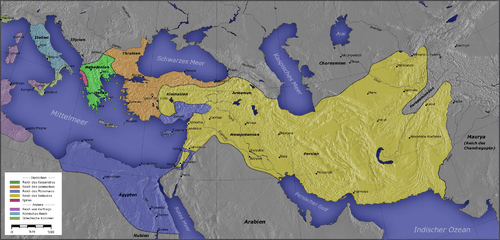

When Alexander died in 323 BC, Ptolemy is said to have instigated the resettlement of the empire made at Babylon. Through the Partition of Babylon, he was appointed satrap of Egypt, under the nominal kings Philip III Arrhidaeus and the infant Alexander IV; the former satrap, the Greek Cleomenes, stayed on as his deputy. Ptolemy quickly moved, without authorization, to subjugate Cyrenaica.

By custom, kings in Macedonia asserted their right to the throne by burying their predecessor. Probably because he wanted to pre-empt Perdiccas, the imperial regent, from staking his claim in this way, Ptolemy took great pains in acquiring the body of Alexander the Great, placing it temporarily in Memphis, Egypt. Ptolemy then openly joined the coalition against Perdiccas.[9]

Perdiccas appears to have suspected Ptolemy of aiming for the throne himself, and may have decided that Ptolemy was his most dangerous rival. Ptolemy executed Cleomenes for spying on behalf of Perdiccas — this removed the chief check on his authority, and allowed Ptolemy to obtain the huge sum that Cleomenes had accumulated.[9]

Rivalry and wars

In 321 BC, Perdiccas attempted to invade Egypt only to fall at the hands of his own men.[10] Ptolemy's decision to defend the Nile against Perdiccas's attempt to force it ended in fiasco for Perdiccas, with the loss of 2000 men. This failure was a fatal blow to Perdiccas' reputation, and he was murdered in his tent by two of his subordinates. Ptolemy immediately crossed the Nile, to provide supplies to what had the day before been an enemy army. Ptolemy was offered the regency in place of Perdiccas; but he declined.[11] Ptolemy was consistent in his policy of securing a power base, while never succumbing to the temptation of risking all to succeed Alexander.[12]

In the long wars that followed between the different Diadochi, Ptolemy's first goal was to hold Egypt securely, and his second was to secure control in the outlying areas: Cyrenaica and Cyprus, as well as Syria, including the province of Judea. His first occupation of Syria was in 318, and he established at the same time a protectorate over the petty kings of Cyprus. When Antigonus One-Eye, master of Asia in 315, showed dangerous ambitions, Ptolemy joined the coalition against him, and on the outbreak of war, evacuated Syria. In Cyprus, he fought the partisans of Antigonus, and re-conquered the island (313). A revolt in Cyrene was crushed the same year.

In 312, Ptolemy and Seleucus, the fugitive satrap of Babylonia, both invaded Syria, and defeated Demetrius Poliorcetes ("besieger of cities"), the son of Antigonus, in the Battle of Gaza. Again he occupied Syria, and again—after only a few months, when Demetrius had won a battle over his general, and Antigonus entered Syria in force—he evacuated it. In 311, a peace was concluded between the combatants. Soon after this, the surviving 13-year-old king, Alexander IV, was murdered in Macedonia on the orders of Cassander, leaving the satrap of Egypt absolutely his own master.

The peace did not last long, and in 309 Ptolemy personally commanded a fleet that detached the coastal towns of Lycia and Caria from Antigonus, then crossed into Greece, where he took possession of Corinth, Sicyon and Megara (308 BC). In 306, a great fleet under Demetrius attacked Cyprus, and Ptolemy's brother Menelaus was defeated and captured in another decisive Battle of Salamis. Ptolemy's complete loss of Cyprus followed.

The satraps Antigonus and Demetrius now each assumed the title of king; Ptolemy, as well as Cassander, Lysimachus and Seleucus I Nicator, responded by doing the same. In the winter of 306 BC, Antigonus tried to follow up his victory in Cyprus by invading Egypt; but Ptolemy was strongest there, and successfully held the frontier against him. Ptolemy led no further overseas expeditions against Antigonus. However, he did send great assistance to Rhodes when it was besieged by Demetrius (305/304). Pausanias reports that the grateful Rhodians bestowed the name Soter ("saviour") upon him as a result of lifting the siege. This account is generally accepted by modern scholars, although the earliest datable mention of it is from coins issued by Ptolemy II in 263 BC.

When the coalition against Antigonus was renewed in 302, Ptolemy joined it, and invaded Syria a third time, while Antigonus was engaged with Lysimachus in Asia Minor. On hearing a report that Antigonus had won a decisive victory there, he once again evacuated Syria. But when the news came that Antigonus had been defeated and slain by Lysimachus and Seleucus at the Battle of Ipsus in 301, he occupied Syria a fourth time.

The other members of the coalition had assigned all Syria to Seleucus, after what they regarded as Ptolemy's desertion, and for the next hundred years, the question of the ownership of southern Syria (i.e., Judea) produced recurring warfare between the Seleucid and Ptolemaic dynasties. Henceforth, Ptolemy seems to have mingled as little as possible in the rivalries between Asia Minor and Greece; he lost what he held in Greece, but reconquered Cyprus in 295/294. Cyrene, after a series of rebellions, was finally subjugated about 300 and placed under his stepson Magas.

Successor

In 289, Ptolemy made his son by Berenice—Ptolemy II Philadelphus—his co-regent. His eldest (legitimate) son, Ptolemy Keraunos, whose mother, Eurydice, the daughter of Antipater, had been repudiated, fled to the court of Lysimachus. Ptolemy also had a consort in Thaïs, the Athenian hetaera and one of Alexander's companions in his conquest of the ancient world. Ptolemy I Soter died in winter 283 or spring 282 at the age of 84.[13] Shrewd and cautious, he had a compact and well-ordered realm to show at the end of forty years of war. His reputation for bonhomie and liberality attached the floating soldier-class of Macedonians and other Greeks to his service, and was not insignificant; nor did he wholly neglect conciliation of the natives. He was a ready patron of letters, founding the Great Library of Alexandria.[14]

Lost history of Alexander's campaigns

Ptolemy himself wrote an eye-witness history of Alexander's campaigns (now lost).[15] In the second century AD, Ptolemy's history was used by Arrian of Nicomedia as one of his two main primary sources (alongside the history of Aristobulus of Cassandreia) for his own extant Anabasis of Alexander, and hence large parts of Ptolemy's history can be assumed to survive in paraphrase or précis in Arrian's work.[16] Arrian cites Ptolemy by name on only a few occasions, but it is likely enough that large stretches of Arrian's Anabasis ultimately reflect Ptolemy's version of events. Arrian once names Ptolemy as the author "whom I chiefly follow" (Anabasis 6.2.4), and in his Preface claims that Ptolemy seemed to him to be a particularly trustworthy source, "not only because he was present with Alexander on campaign, but also because he was himself a king, and hence lying would be more dishonourable for him than for anyone else" (Anabasis, Prologue).

Ptolemy's lost history was long considered an objective work, distinguished by its straightforward honesty and sobriety, but more recent work has called this assessment into question. R. M. Errington argued that Ptolemy's history was characterised by persistent bias and self-aggrandisement, and by systematic blackening of the reputation of Perdiccas, one of Ptolemy's chief dynastic rivals after Alexander's death.[17] For example, Arrian's account of the fall of Thebes in 335 BC (Anabasis 1.8.1-1.8.8, a rare section of narrative explicitly attributed to Ptolemy by Arrian) shows several significant variations from the parallel account preserved in Diodorus Siculus (17.11-12), most notably in attributing a distinctly unheroic role in proceedings to Perdiccas. More recently, J. Roisman has argued that the case for Ptolemy's blackening of Perdiccas and others has been much exaggerated.[18]

Euclid

Ptolemy personally sponsored the great mathematician Euclid, but found Euclid's seminal work, the Elements, too difficult to study, so he asked if there were an easier way to master it. According to Proclus Euclid famously quipped: "Sire, there is no Royal Road to geometry."[19]

Fictional portrayals

- Ptolemy was played by Virgilio Teixeira in the film Alexander the Great (1956) and by Robert Earley, Elliot Cowan, and Anthony Hopkins in the Oliver Stone film Alexander (2004).

Gallery

A rare coin of Ptolemy I, a reminder of his successful campaigns with Alexander in India. Obv: Ptolemy in profile at the beginning of his reign.Rev: Alexander triumphantly riding a chariot drawn by elephants.

A rare coin of Ptolemy I, a reminder of his successful campaigns with Alexander in India. Obv: Ptolemy in profile at the beginning of his reign.Rev: Alexander triumphantly riding a chariot drawn by elephants. Ptolemy coin with Alexander wearing an elephant scalp, symbol of his conquest of India.

Ptolemy coin with Alexander wearing an elephant scalp, symbol of his conquest of India.

Tetradrachm with portrait of Ptolemy I, British Museum, London

Tetradrachm with portrait of Ptolemy I, British Museum, London

See also

![]() Media related to Ptolemy I at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Ptolemy I at Wikimedia Commons

- History of Ptolemaic Egypt

- Serapis Greco-Egyptian political appeasement god for the Greek and Egyptian masses, ordered into existence by Ptolemy I

References

- ↑ The decree of Ptolemy Lagides

- ↑ Jones, Prudence J. (2006). Cleopatra: A Sourcebook. University of Oklahoma Press. p. 14.

They were members of the Ptolemaic dynasty of Macedonian Greeks, who ruled Egypt after the death of its conqueror, Alexander the Great.

- ↑ Pomeroy, Sarah B. (1990). Women in Hellenistic Egypt. Wayne State University Press. p. 16.

while Ptolemaic Egypt was a monarchy with a Greek ruling class.

- ↑ Redford, Donald B., ed. (2000). The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press.

Cleopatra VII was born to Ptolemy XII Auletes (80–57 BCE, ruled 55–51 BCE) and Cleopatra, both parents being Macedonian Greeks.

- ↑ Bard, Kathryn A., ed. (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. p. 488.

Ptolemaic kings were still crowned at Memphis and the city was popularly regarded as the Egyptian rival to Alexandria, founded by the Macedonian Greeks.

- ↑ Bard, Kathryn A., ed. (1999). Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt. Routledge. p. 687.

During the Ptolemaic period, when Egypt was governed by rulers of Greek descent...

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 382

- ↑ Arrian 1976, III, 30

- 1 2 Peter Green, Alexander to Actium, 1990, pp 13-14

- ↑ Anson, Edward M (Summer 1986). "Diodorus and the Date of Triparadeisus". The American Journal of Philology (The Johns Hopkins University Press) 107 (2): 208–217. doi:10.2307/294603. JSTOR 294603.

- ↑ Peter Green p14

- ↑ Peter Green pp 119

- ↑ "Ptolemy I". www.tyndalehouse.com. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- ↑ Phillips, Heather A., "The Great Library of Alexandria?". Library Philosophy and Practice, August 2010

- ↑ Jacoby, Felix (1926). Die Fragmente der griechischen Historiker, Teil 2, Zeitgeschichte. - B. Spezialgeschichten, Autobiographien und Memoiren, Zeittafeln [Nr. 106-261]. Berlin: Weidmann. pp. 752–769, no. 138, "Ptolemaios Lagu".

- ↑ Bosworth, A. B. (1988). From Arrian to Alexander: Studies in Historical Interpretation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 13–14. ISBN 0198148631.

- ↑ Errington, R. M. (1969-01-01). "Bias in Ptolemy's History of Alexander". The Classical Quarterly. 19 (2): 233–242. JSTOR 637545.

- ↑ Roisman, Joseph (1984-01-01). "Ptolemy and His Rivals in His History of Alexander". The Classical Quarterly. 34 (2): 373–385. JSTOR 638295.

- ↑ Robinson, Victor (2005). The Story of Medicine. Kessinger Publishing. p. 80. ISBN 978-1-4191-5431-7.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "article name needed". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Bibliography

- Walter M. Ellis: Ptolemy of Egypt, London 1993.

- Christian A. Caroli: Ptolemaios I. Soter - Herrscher zweier Kulturen, Konstanz 2007.

- Waterfield, Robin (2011). Dividing the Spoils - The War for Alexander the Great’s Empire (hardback). New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 273 pages. ISBN 978-0-19-957392-9.

External links

- Ptolemy Soter I at LacusCurtius — (Chapter II of E. R Bevan's House of Ptolemy, 1923)

- Ptolemy I (at Egyptian Royal Genealogy, with genealogical table)

- Livius, Ptolemy I Soter by Jona Lendering

- Ptolemy I Soter entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

- A genealogical tree of Ptolemy, though not necessarily reliable Alexander the Great

| Ptolemy I Soter Born: 367 BC Died: 283 BC | ||

| Preceded by Alexander IV |

Pharaoh of Egypt 305–283/2 BC |

Succeeded by Ptolemy II Philadelphus |