Personality test

| Personality test | |

|---|---|

| Diagnostics | |

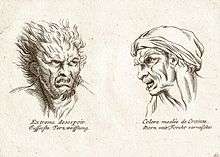

The four temperaments as illustrated by Johann Kaspar Lavater | |

| MeSH | D010556 |

A personality test is a questionnaire or other standardized instrument designed to reveal aspects of an individual's character or psychological makeup.

The first personality tests were developed in the 1920s[1] and were intended to ease the process of personnel selection, particularly in the armed forces. Since these early efforts, a wide variety of personality tests have been developed, notably the Myers–Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI), the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI), and a number of tests based on the five factor model of personality, such as the Revised NEO Personality Inventory.

Estimates of how much the industry is worth are between $2 and $4 billion a year.[2] Personality tests are used in a range of contexts, including individual and relationship counseling, career counseling, employment testing, occupational health and safety and customer interaction management.

History

The origins of personality testing date back to the 18th and 19th centuries, when personality was assessed through phrenology, the measurement of the human skull, and physiognomy, which assessed personality based on a person's outer appearances.[3] Sir Francis Galton took another approach to assessing personality late in the 19th century. Under the assumption of the lexical hypothesis, Galton estimated the number of adjectives that described personality in the English dictionary[4] Galton's list was eventually refined by Thurstone to 60 words that were commonly used for describing personality at the time.[4] Through factor analyzing responses from 1300 participants Thurstone was able to reduce these sixty adjectives into five common factors.[4] This procedure of factor analyzing common adjectives was later utilized by Raymond Cattell who likewise produced a data set that eventually showed a five factor structure. Work by numerous other researchers over the proceeding decades produced additional support for the five factor structure. McCrae and Costa operationalized these five factors of personality into the measure known as the NEO-PI, one of the most well used versions of the five factor model.[4]

Another early personality test was the Woodworth Personal Data Sheet, a self-report inventory developed for World War I and used for the psychiatric screening of new draftees.[3]

Overview

There are many different types of personality tests. The most common type is the self-report inventory, also commonly referred to as objective personality tests. Self-report inventory tests involve the administration of many questions/items to test-takers who respond by rating the degree to which each item reflects their behaviour and can be scored objectively. The term 'item' is used because many test questions are not actually questions; they are typically statements on questionnaires that allow respondents to indicate level of agreement (using a Likert scale or, more accurately, a Likert-type scale).

A sample item on a personality test, for example, might ask test-takers to rate the degree to which they agree with the statement "I talk to a lot of different people at parties" by using a scale of 1 ("strongly disagree") to 5 ("strongly agree"). The most widely used objective test of personality is the Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory (MMPI) which was originally designed to distinguish individuals with different psychological problems. Since then, it has become popular as a means of attempting to identify personality characteristics of people in many every-day settings.[5] In addition to self-report inventories, there are many other methods for assessing personality, including observational measures, peer-report studies, and projective tests (e.g. the TAT and Ink Blots).

Topics

Norms

The meaning of personality test scores are difficult to interpret in a direct sense. For this reason substantial effort is made by producers of personality tests to produce norms to provide a comparative basis for interpreting a respondent's test scores. Common formats for these norms include percentile ranks, z scores, sten scores, and other forms of standardised scores.

Test development

A substantial amount of research and thinking has gone into the topic of personality test development. Development of personality tests tends to be an iterative process whereby a test is progressively refined. Test development can proceed on theoretical or statistical grounds. There are three commonly used general strategies: Inductive, Deductive, and Empirical.[6] Scales created today will often incorporate elements of all three methods.

Deductive assessment construction begins by selecting a domain or construct to measure.[7] The construct is thoroughly defined by experts and items are created which fully represent all the attributes of the construct definition.[7] Test items are then selected or eliminated based upon which will result in the strongest internal validity for the scale. Measures created through deductive methodology are equally valid and take significantly less time to construct compared to inductive and empirical measures. The clearly defined and face valid questions that result from this process make them easy for the person taking the assessment to understand. Although subtle items can be created through the deductive process,[8] these measure often are not as capable of detecting lying as other methods of personality assessment construction.[7]

Inductive assessment construction begins with the creation of a multitude of diverse items.The items created for an inductive measure to not intended to represent any theory or construct in particular. Once the items have been created they are administered to a large group of participants. This allows researchers to analyze natural relationships among the questions and label components of the scale based upon how the questions group together. Several statistical techniques can be used to determine the constructs assessed by the measure. Exploratory Factor Analysis and Confirmatory Factor Analysis are two of the most common data reduction techniques that allow researchers to create scales from responses on the initial items.

The Five Factor Model of personality was developed using this method.[9] Advanced statistical methods include the opportunity to discover previously unidentified or unexpected relationships between items or constructs. It also may allow for the development of subtle items that prevent test takers from knowing what is being measured and may represent the actual structure of a construct better than a pre-developed theory.[10] Criticisms include a vulnerability to finding item relationships that do not apply to a broader population, difficulty identifying what may be measured in each component because of confusing item relationships, or constructs that were not fully addressed by the originally created questions.[11]

Empirically derived personality assessments also require statistical techniques. One of the central goals of empirical personality assessment is to create a test that validity discriminates between two personality features. For example, this may include depressed and non-depressed individuals, or individuals high or low in levels of aggression. In order to accomplish this goal items are selected that differentiate between the personality trait being assessed. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory was initially developed using this method.[12]

Test evaluation

There are several criteria for evaluating a personality test. Fundamentally, a personality test is expected to demonstrate reliability and validity.

Analysis

A respondent's response is used to compute the analysis. Analysis of data is a long process. Two major theories are used here; Classical test theory (CTT)- used for the observed score,[13] and item response theory (IRT)- "a family of models for persons' responses to items".[14][15] The two theories focus upon different 'levels' of responses and researchers are implored to use both in order to fully appreciate their results.

Non-response

Firstly, item non-response needs to be addressed. Non-response can either be 'unit'- where a person gave no response for any of the n items, or 'item'- i.e., individual question. Unit non-response is generally dealt with exclusion.[16] Item non-response should be handled by imputation- the method used can vary between test and questionnaire items. Literature about the most appropriate method to use and when can be found here.[17]

Scoring

The conventional method of scoring items is to assign '0' for an incorrect answer '1' for a correct answer. When tests have more response options (e.g. ordinal-polytomous items)- '0' when incorrect, '1' for being partly correct and '2' for being correct.[16] Personality tests can also be scored using a dimensional (normative) or a typological (ipsative) approach. Dimensional approaches such as the Big 5 describe personality as a set of continuous dimensions on which individuals differ. From the item scores, an 'observed' score is computed. This is generally found by summing the un-weighted item scores.

Criticism and controversy

Biased test taker interpretation

One problem of a personality test is that the users of the test could only find it accurate because of the subjective validation involved. Users of personality tests have to assume that the subjective responses that are given by participants on such tests, represent the actual personality of those participants. Also, one must assume that personality is a reliable, constant part of the human mind or behaviour.

Personality versus social factors

In the 60s and 70s some psychologists dismissed the whole idea of personality, considering much behaviour to be context-specific.[18] This idea was supported by the fact that personality often does not predict behaviour in specific contexts. However, more extensive research has shown that when behaviour is aggregated across contexts, that personality can be a modest to good predictor of behaviour. Almost all psychologists now acknowledge that both social and individual difference factors (i.e., personality) influence behaviour. The debate is currently more around the relative importance of each of these factors and how these factors interact.

Respondent faking

One problem with self-report measures of personality is that respondents are often able to distort their responses.[19] Emotive tests in particular could in theory become prey to unreliable results due to people striving to pick the answer they feel the best fitting of an ideal character and therefore not their true response. This is particularly problematic in employment contexts and other contexts where important decisions are being made and there is an incentive to present oneself in a favourable manner.

Work in experimental settings[20] has also shown that when student samples have been asked to deliberately fake on a personality test, they clearly demonstrated that they are capable of doing so. Hogan, Barett and Hogan (2007)[21] analyzed data of 5,266 applicants who did a personality test based on the big five. At the first application the applicants were rejected. After six months the applicants reapplied and completed the same personality test. The answers on the personality tests were compared and there was no significant difference between the answers.

So in practice, most people do not significantly distort. Nevertheless, a researcher has to be prepared for such possibilities. Also, sometimes participants think that tests results are more valid than they really are because they like the results that they get. People want to believe that the positive traits that the test results say they possess are in fact present in their personality. This leads to distorted results of people's sentiments on the validity of such tests.

Several strategies have been adopted for reducing respondent faking. One strategy involves providing a warning on the test that methods exist for detecting faking and that detection will result in negative consequences for the respondent (e.g., not being considered for the job). Forced choice item formats (ipsative testing) have been adopted which require respondents to choose between alternatives of equal social desirability. Social desirability and lie scales are often included which detect certain patterns of responses, although these are often confounded by true variability in social desirability.

More recently, Item Response Theory approaches have been adopted with some success in identifying item response profiles that flag fakers. Other researchers are looking at the timing of responses on electronically administered tests to assess faking. While people can fake in practice they seldom do so to any significant level. To successfully fake means knowing what the ideal answer would be. Even with something as simple as assertiveness people who are unassertive and try to appear assertive often endorse the wrong items. This is because unassertive people confuse assertion with aggression, anger, oppositional behavior, etc.

Psychological research

Research on the importance of personality and intelligence in education shows evidence that when others provide the personality rating, rather than providing a self-rating, the outcome is nearly four times more accurate for predicting grades. Therefore with respect to learning, personality is more useful than intelligence for guiding both students and teachers.[22]

Additional applications

A study by American Management Association reveals that 39 percent of companies surveyed use personality testing as part of their hiring process. However, ipsative personality tests are often misused in recruitment and selection, where they are mistakenly treated as if they were normative measures.[23]

More people are using personality testing to evaluate their business partners, their dates and their spouses. Salespeople are using personality testing to better understand the needs of their customers and to gain a competitive edge in the closing of deals. College students have started to use personality testing to evaluate their roommates. Lawyers are beginning to use personality testing for criminal behavior analysis, litigation profiling, witness examination and jury selection.

Dangers

Personality tests have been around for a long time, but it wasn't until it became illegal for employers to use polygraphs that we began to see the widespread use of personality tests. The idea behind these personality tests is that employers can reduce their turnover rates and prevent economic losses in the form of people prone to thievery, drug abuse, emotional disorders or violence in the workplace.

Employers may also view personality tests as more accurate assessment of a candidate's behavioral characteristics versus an employment reference. But the problem with using personality tests as a hiring tool is the notion a person's job performance in one environment will carry over to another work environment. However, the reality is that one's environment plays a crucial role in determining job performance, and not all environments are created equally. One danger of using personality tests is the results may be skewed based on a person's mood so good candidates may potentially be screened out because of unfavorable responses that reflect that mood.

Another danger of personality tests is that they can create false-negative results (i.e. honest people being labeled as dishonest) especially in cases when stress on the applicant's part is involved. There is also the issue of privacy to be of concern forcing applicants to reveal private thoughts and feelings through his or her responses that seem to become a condition for employment. Another danger of personality tests is the illegal discrimination of certain groups under the guise of a personality test.[24]

Examples

- The first modern personality test was the Woodworth Personal Data Sheet, which was first used in 1919. It was designed to help the United States Army screen out recruits who might be susceptible to shell shock.

- The Rorschach inkblot test was introduced in 1921 as a way to determine personality by the interpretation of inkblots.

- The Thematic Apperception Test was commissioned by the Office of Strategic Services (O.S.S.) in the 1930s to identify personalities that might be susceptible to being turned by enemy intelligence.

- The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory was published in 1942 as a way to aid in assessing psychopathology in a clinical setting. It can also be used to assess the Personality Psychopathology Five (PSY-5),[25] which are similar to the Five Factor Model (FFM; or Big Five personality traits). These five scales on the MMPI-2 include aggressiveness, psychoticism, disconstraint, negative emotionality/neuroticism, and introversion/low positive emotionality.

- Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) is a psychometric questionnaire designed to measure psychological preferences in how people perceive the world and make decisions. This 16-type indicator test is based on Carl Jung's Psychological Types, developed during World War II by Isabel Myers and Katharine Briggs. The 16-type indicator includes a combination of Extroversion-Introversion, Sensing-Intuition, Thinking-Feeling and Judging-Perceiving.The MBTI utilizes 2 opposing behavioral divisions on 4 scales that yields a "personality type".

- Keirsey Temperament Sorter developed by David Keirsey is influenced by Isabel Myers sixteen types and Ernst Kretschmer's four types.

- The True Colors (personality) Test developed by Don Lowry in 1978 is based on the work of David Keirsey in his book, "Please Understand Me" as well as the Myers-Briggs Type Indicator and provides a model for understanding personality types using the colors blue, gold, orange and green to represent four basic personality temperaments.[26]

- The 16PF Questionnaire (16PF) was developed by Raymond Cattell and his colleagues in the 1940s and 1950s in a search to try to discover the basic traits of human personality using scientific methodology. The test was first published in 1949, and is now in its 5th edition, published in 1994. It is used in a wide variety of settings for individual and marital counseling, career counseling and employee development, in educational settings, and for basic research.

- The EQSQ Test developed by Simon Baron-Cohen, Sally Wheelwright centers on the empathizing-systemizing theory of the male versus the female brain types.

- The Personality and Preference Inventory (PAPI), originally designed by Dr Max Kostick, Professor of Industrial Psychology at Boston State College, in Massachusetts, USA, in the early 1960s evaluates the behaviour and preferred work styles of individuals.

- The Strength Deployment Inventory, developed by Elias Porter in 1971 and is based on his theory of Relationship Awareness. Porter was the first known psychometrician to use colors (Red, Green and Blue) as shortcuts to communicate the results of a personality test.[27]

- The Newcastle Personality Assessor (NPA), created by Daniel Nettle, is a short questionnaire designed to quantify personality on five dimensions: Extraversion, Neuroticism, Conscientious, Agreeableness, and Openness.[28]

- The DISC assessment is based on the research of William Moulton Marston and later work by John Grier, and identifies four personality types: Dominance; Influence; Steadiness and Conscientiousness. It is used widely in Fortune 500 companies, for-profit and non-profit organizations.

- The Winslow Personality Profile measures 24 traits on a decile scale. It has been used in the National Football League, the National Basketball Association, the National Hockey League and every draft choice for Major League Baseball for the last 30 years[29] and can be taken online for personal development.[30]

- Other personality tests include Forté Profile, Millon Clinical Multiaxial Inventory, Eysenck Personality Questionnaire, Swedish Universities Scales of Personality, Edwin E. Wagner's The Hand Test, and Enneagram of Personality.

- The HEXACO Personality Inventory – Revised (HEXACO PI-R) is based on the HEXACO model of personality structure, which consists of six domains, the five domains of the Big Five model, as well as the domain of Honesty-Humility.[31]

- The Pro Development assessment is a professional development instrument for leaders that measures convergence of an individual’s Missions – (motivations and interests that excite an individual to action), Competencies – (abilities and aptitudes that enable action) and Styles – (personality and behaviors that make an individual unique). PRO-D also produces an astonishingly accurate perspective of how the different dimensions of mission, style and competency interact for the Person – Role – Organization. It was developed in Princeton under the advisement of George Gallup and Win Manning (ETS).[32]

- The Personality Inventory for DSM-5 (PID-5) was developed in September 2012 by the DSM-5 Personality and Personality Disorders Workgroup with regard to a personality trait model proposed for DSM-5. The PID-5 includes 25 maladaptive personality traits as determined by Krueger, Derringer, Markon, Watson, and Skodol.[33]

- The Process Communication Model (PCM), developed by Taibi Kahler with NASA funding,[34] was used to assist with shuttle astronaut selection. Now it is a non-clinical personality assessment, communication and management methodology that is now applied to corporate management, interpersonal communications, education, and real-time analysis of call centre interactions[35][36] among other uses.

- The Birkman Method (TBM) was developed by Roger W. Birkman in the late 1940s. The instrument consists of ten scales describing "occupational preferences" (Interests), 11 scales describing "effective behaviors" (Usual behavior) and 11 scales describing interpersonal and environmental expectations (Needs). A corresponding set of 11 scale values was derived to describe "less than effective behaviors" (Stress behavior). TBM was created empirically. The psychological model is most closely associated with the work of Kurt Lewin. Occupational profiling consists of 22 job families with over 200 associated job titles connected to O*Net.

- The International Personality Item Pool (IPIP) is a public domain set of more than 2000 personality items which can be used to measure many personality variables, including the Five Factor Model.[37]

Personality tests of the five factor model

Different types of the Big Five personality traits:

- The NEO PI-R, or the Revised NEO Personality Inventory, is one of the most significant measures of the Five Factor Model (FFM). The measure was created by Costa and McCrae and contains 240 items in the forms of sentences. Costa and McCrae had divided each of the five domains into six facets each, 30 facets total, and changed the way the FFM is measured.[38]

- The Five-Factor Model Rating Form (FFMRF) was developed by Lynam and Widiger in 2001 as a shorter alternative to the NEO PI-R. The form consists of 30 facets, 6 facets for each of the Big Five factors.[39]

- The Ten-Item Personality Inventory (TIPI) and the Five Item Personality Inventory (FIPI) are very abbreviated rating forms of the Big Five personality traits.[40]

- The Five Factor Personality Inventory — Children (FFPI-C) was developed to measure personality traits in children based upon the Five Factor Model (FFM).[41]

- The Big Five Inventory (BFI), developed by John, Donahue, and Kentle, is a 44-item self-report questionnaire consisting of adjectives that assess the domains of the Five Factor Model (FFM).[42] The 10-Item Big Five Inventory is a simplified version of the well-established BFI. It is developed to provide a personality inventory under time constraints. The BFI-10 assesses the 5 dimensions of BFI using only two items each to cut down on length of BFI.[43]

- The Semi-structured Interview for the Assessment of the Five-Factor Model (SIFFM) is the only semi-structured interview intended to measure a personality model or personality disorder. The interview assesses the five domains and 30 facets as presented by the NEO PI-R, and it additional assesses both normal and abnormal extremities of each facet.[44]

See also

References

- ↑ Saccuzzo, , Dennis P.; Kaplan, Robert M. (2009). Psychological Testing: Principles, Applications, and Issues (7th ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Cengage Learning. ISBN 0495095559.

- ↑ "Personality Testing at Work: Emotional Breakdown". The Economist.

- 1 2 Elahe Nezami; James N. Butcher (16 February 2000). G. Goldstein; Michel Hersen, eds. Handbook of Psychological Assessment. Elsevier. p. 415. ISBN 978-0-08-054002-3.

- 1 2 3 4 Goldberg, L.R. (1993). "The structure of phenotypic personality traits". American Psychologist. 48 (1): 26–34. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.48.1.26.

- ↑ Carlson [et al.], Neil, R. (2010). Psychology: the Science of Behaviour. United States of America: Person Education. p. 464. ISBN 978-0-205-64524-4.

- ↑ Burisch, Matthias (March 1984). "Approaches to personality inventory construction: A comparison of merits". American Psychologist. 39 (3): 214–227. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.39.3.214.

- 1 2 3 Burisch, M (1984). "Approaches to personality inventory construction: A comparison of merits". American Psychologist. 39 (3): 214. doi:10.1037/0003-066x.39.3.214.

- ↑ Jackson, D. N. (1971). "The dynamics of structured personality tests: 1971". Psychological Review. 78 (3): 229. doi:10.1037/h0030852.

- ↑ McCrae, Robert; Oliver John (1992). "An Introduction to the Five-Factor Model and Its Applications". Journal of Personality. 60 (2): 175–215. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1992.tb00970.x. PMID 1635039.

- ↑ Smith, Greggory; Sarah Fischer; Suzannah Fister (December 2003). "Incremental Validity Principles in Test Construction". Psychological Assessment. 15 (4): 467–477. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.15.4.467.

- ↑ Ryan Joseph; Shane Lopez; Scott Sumerall (2001). William Dorfman, Michel Hersen, ed. Understanding Psychological Assessment: Perspective on Individual Differences (1 ed.). Springer. pp. 1–15.

- ↑ Hathaway, S. R.; McKinley, J. C. (1940). "A multiphasic personality schedule(Minnesota): I. Construction of the schedule". Journal of Psychology. 10: 249–254. doi:10.1080/00223980.1940.9917000.

- ↑ (see Lord and Novick, 1968)

- ↑ Herman J. Adèr, Gideon J. Mellenbergh (2008) Advising on Research Methods: a consultant's companion. Johannes van Kessel Publ. p. 244.

- ↑ See Hamleton and Swaminathon (1985) for a full summary of IRT

- 1 2 (Mellenbergh, 2008)

- ↑ (Ader, Mellenbergh & Hand, 2008)

- ↑ Doll, Edgar Arnold (1953). The measurement of social competence: a manual for the Vineland social maturity scale. Educational Test Bureau, Educational Publishers. doi:10.1037/11349-000. archived at

- ↑ Arendasy, M.; Sommer, Herle; Schutzhofer, Inwanschitz (2011). "Modeling effects of faking on an objective personality test.". Journal of Individual Differences. 32 (4): 210–218. doi:10.1027/1614-0001/a000053.

- ↑ (e.g., Viswesvaran & Ones, 1999; Martin, Bowen & Hunt, 2002)

- ↑ Hogan, Joyce. "Personality Measurement, Faking, and Employment Selection" (PDF). American Psychological Association.

- ↑ Poropat, Arthur E. (2014-08-01). "Other-rated personality and academic performance: Evidence and implications". Learning and Individual Differences. 34: 24–32. doi:10.1016/j.lindif.2014.05.013.

- ↑ Blinkhorn, S.; Johnson, C.; Wood, R. (1988). "Spuriouser and spuriouser:The use of ipsative personality tests". Journal of Occupational. Psychology. 61: 153–162.

- ↑ Stabile, Susan J. "The Use of Personality Tests as a Hiring Tool: Is the Benefit Worth the Cost?" (PDF). U.PA. Journal of Labor and Employment Law.

- ↑ Harkness, A. R., & McNulty, J. L. (1994). The Personality Psychopathology Five (PSY-5): Issue from the pages of a diagnostic manual instead of a dictionary. In S. Strack & M. Lorr (Eds.), Differentiating normal and abnormal personality. New York: Springer.

- ↑ "International True Colors Association". Retrieved 2013-01-03.

- ↑ Porter, Elias H. (1971) Strength Deployment Inventory, Pacific Palisades, CA: Personal Strengths Assessment Service.

- ↑ Nettle, Daniel (2009-03-07). "A test of character". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "How to Build the Perfect Batter". GQ Magazine. Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- ↑ "Winslow Online Personality Assessment". Retrieved 2012-07-26.

- ↑ Ashton, M. C.; Lee, K. (2008). "The prediction of Honesty-Humility-related criteria by the HEXACO and Five-Factor models of personality". Journal of Research in Personality. 42: 1216–1228. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2008.03.006.

- ↑ "Pro-D Online Assessment". Retrieved 2012-12-18.

- ↑ Krueger, R. F.; Derringer, J.; Markon, K. E.; Watson, D.; Skodol, A. E. (2012). "Initial construction of a maladaptive personality trait model and inventory for DSM-5". Psychological Medicine. 42: 1879–1890. doi:10.1017/s0033291711002674.

- ↑ Spenser, Scott. "The History of the Process Communication Model in Astronaut Selection", Cornell University, December 2000. Retrieved 19 June 2013

- ↑ Conway, Kelly (2008). "Methods and systems for determining customer hang-up during a telephonic communication between a customer and a contact center". US Patent Office.

- ↑ Steiner, Christopher (2012). “Automate This: How Algorithms Came to Rule Our World”. Penguin Group (USA) Inc., New York. ISBN 9781101572153.

- ↑ Goldberg, L. R.; Johnson, J. A.; Eber, H. W.; Hogan, R.; Ashton, M. C.; Cloninger, C. R.; Gough, H. C. (2006). "The International Personality Item Pool and the future of public-domain personality measures". Journal of Research in Personality. 40: 84–96. doi:10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.007.

- ↑ Costa, P. T., Jr., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.

- ↑ Lynam, D. R.; Widiger, T. A. (2001). "Using the five-factor model to represent the DSM-IV personality disorders: An expert consensus approach". Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 110: 401–412. doi:10.1037/0021-843x.110.3.401.

- ↑ Gosling, Samuel D; Rentfrow, Peter J; Swann, William B (2003). "A very brief measure of the Big-Five personality domains". Journal of Research in Personality. 37 (6): 504–528. doi:10.1016/S0092-6566(03)00046-1. ISSN 0092-6566.

- ↑ McGhee, R.L., Ehrler, D. & Buckhalt, J. (2008). Manual for the Five Factor Personality Inventory — Children Austin, TX (PRO ED, INC).

- ↑ John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). The Big Five Inventory – Versions 4a and 54. Berkeley: University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research.

- ↑ Beatrice Rammstedt (2007). The 10-Item Big Five Inventory: Norm Values and Investigation of Sociodemographic Effects Based on a German Population Representative Sample. European Journal of Psychological Assessment (July 2007), 23 (3), pg. 193-201

- ↑ Trull, T. J., & Widiger, T. A. (1997). Structured Interview for the Five-Factor Model of Personality. Odessa, FL: Psychological Assessment Resources.