History of Slovenia

The history of Slovenia chronicles the period of the Slovene territory from the 5th century BC to the present. In the Early Bronze Age, Proto-Illyrian tribes settled an area stretching from present-day Albania to the city of Trieste. Slovenian territory was part of the Roman Empire, and it was devastated by Barbarian incursions in late Antiquity and Early Middle Ages, since the main route from the Pannonian plain to Italy ran through present-day Slovenia. Alpine Slavs, ancestors of modern-day Slovenes, settled the area in the late 6th Century A.D. The Holy Roman Empire controlled the land for nearly 1,000 years, and between the mid 14th century and 1918 most of Slovenia was under Habsburg rule. In 1918, Slovenes joined Yugoslavia, while the west of the country was annexed to Italy. Between 1945 and 1990, Slovenia was under SFRJ(Yugoslavia). The country gained its independence from Yugoslavia in June 1991, and is today a member of the European Union and NATO.

Prehistory to Slavic settlement

Prehistory

The earliest signs of human settlement in present-day Slovenia were found in Hell Cave in the Loza Woods near Orehek in Inner Carniola, where two stone tools approximately 250,000 years old were recovered. During the last glacial period, present-day Slovenia was inhabited by Neanderthals; the most famous Neanderthal archaeological site in Slovenia is a cave close to the village of Šebrelje near Cerkno, where the Divje Babe flute, the oldest known musical instrument in the world was found in 1995. In the transition period between the Bronze age to the Iron age, the Urnfield culture flourished. Numerous archeological remains dating from the Hallstatt period have been found in Slovenia, with important settlements in Most na Soči, Vače, and Šentvid pri Stični. Novo Mesto in Lower Carniola, one of the most important archaeological sites of the Hallstatt culture, has been nicknamed the "City of Situlas" after numerous situlas found in the area.[2]

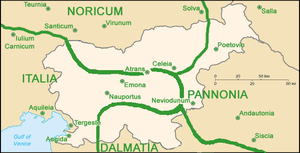

Ancient Romans

In the Iron Age, present-day Slovenia was inhabited by Illyrian and Celtic tribes until the 1st century BC, when the Romans conquered the region establishing the provinces of Pannonia and Noricum. What is now western Slovenia was included directly under Roman Italia as part of the X region Venetia et Histria. Important Roman towns located in present-day Slovenia included Emona, Celeia and Poetovio. Other important settlements were Nauportus, Neviodunum, Haliaetum, Atrans, and Stridon.

During the migration period, the region suffered invasions of many barbarian armies, due to its strategic position as the main passage from the Pannonian plain to the Italian peninsula. Rome finally abandoned the region at the end of the 4th century. Most cities were destroyed, while the remaining local population moved to the highland areas, establishing fortified towns. In the 5th century, the region was part of the Ostrogothic kingdom, and was later contested between the Ostrogoths, the Byzantine Empire and the Lombards.

Slavic settlement

The Slavic ancestors of present-day Slovenes settled in the East Alpine area at the end of the 6th century. Coming from two directions, North (via today's East Austria and Czech Republic), settling in the area of today's Carinthia and west Styria and South (via today's Slavonia), settling in the area of today's central Slovenia.

King Samo

This Slavic tribe, also known as the Alpine Slavs, was submitted to Avar rule before joining the Slavic King Samo's tribal union in 623 AD. After Samo's death, the Slavs of Carniola (in present-day Slovenia) again fell to Avar rule, while the Slavs north of the Karavanke range (in present-day Austrian regions of Carinthia, Styria and East Tyrol) established the independent principality of Carantania.

The Middle Ages

Carantania to Carinthia

In 745, Carantania and the rest of Slavic-populated territories of present-day Slovenia, being pressured by newly consolidated Avar power, submitted to Bavarian overrule and were, together with the Duchy of Bavaria, incorporated into the Carolingian Empire, while Carantanians and other Slavs living in present Slovenia converted to Christianity. The eastern part of Carantania was ruled again by Avars between 745 and 795.

Carantania retained its internal independence until 828 when the local princes, following the anti-Frankish rebellion of Ljudevit Posavski, were deposed and gradually replaced by a Germanic (primarily Bavarian) ascendancy. Under Emperor Arnulf of Carinthia, Carantania, now ruled by a mixed Bavarian-Slav nobility, shortly emerged as a regional power, but was destroyed by the Hungarian invasions in the late 9th century.

Carantania-Carinthia was established again as an autonomous administrative unit in 976, when Emperor Otto I, "the Great", after deposing the Duke of Bavaria, Henry II, "the Quarreller", split the lands held by him and made Carinthia the sixth duchy of the Holy Roman Empire, but old Carantania never developed into a unified realm.

In the late 10th and beginning of the 11th century, primarily because of the Hungarian threat, the south-eastern border region of the German Empire was organized into so called "marks", that became the core of the development of the historical Slovenian lands, the Carniola, the Styria and the western Goriška/Gorizia. The consolidation and formation of the historical Slovenian lands took place in a long period between 11th and 14th century being led by a number of important feudal families such as the Dukes of Spannheim, the Counts of Gorizia, the Counts of Celje and finally the House of Habsburg.

Slovenes as a distinct ethnic group

The first mentions of a common Slovene ethnic identity, transcending regional boundaries, date from the 16th century.[3]

During the 14th century, most of the Slovene Lands passed under the Habsburg rule. In the 15th century, the Habsburg domination was challenged by the Counts of Celje, but by the end of the century the great majority of Slovene-inhabited territories were incorporated into the Habsburg Monarchy. Most Slovenes lived in the administrative region known as Inner Austria, forming the majority of the population of the Duchy of Carniola and the County of Gorizia and Gradisca, as well as of Lower Styria and southern Carinthia.

Slovenes also inhabited most of the territory of the Imperial Free City of Trieste, although representing the minority of its population.[4]

Early modern period

In the 16th century, the Protestant Reformation spread throughout the Slovene Lands. During this period, the first books in the Slovene language were written by the Protestant preacher Primož Trubar and his followers, establishing the base for the development of the standard Slovene language. In the second half of the 16th century, numerous books were printed in Slovene, including an integral translation of the Bible by Jurij Dalmatin. During the Counter-Reformation in the late 16th and 17th centuries, led by the bishop of Ljubljana Thomas Chrön and Seckau Martin Brenner, almost all Protestants were expelled from the Slovene Lands (with the exception of Prekmurje). Nevertheless, they left a strong legacy in the tradition of Slovene culture, which was partially incorporated in the Catholic Counter-Reformation in the 17th century. The old Slovene orthography, also known as Bohorič's Alphabet, which was developed by the Protestants in the 16th century and remained in use until the mid-19th century, testified to the unbroken tradition of Slovene culture as established in the years of the Protestant Reformation.

Between the 15th and the 17th century, the Slovene Lands suffered many calamities. Many areas, especially in southern Slovenia, were devastated by the Ottoman-Habsburg Wars. Many flourishing towns, like Vipavski Križ and Kostanjevica na Krki, were completely destroyed by incursions of the Ottoman Army, and never recovered. The nobility of the Slovene-inhabited provinces had an important role in the fight against the Ottoman Empire. The Carniolan noblemen's army thus defeated the Ottomans in the Battle of Sisak of 1593, marking the end of the immediate Ottoman threat to the Slovene Lands, although sporadic Ottoman incursions continued well into the 17th century.

.jpg)

In the 16th and 17th century, the western Slovene regions became the battlefield of the wars between the Habsburg Monarchy and the Venetian Republic, most notably the War of Gradisca, which was largely fought in the Slovene Goriška region. Between late 15th and early 18th century, the Slovene lands also witnessed many peasant wars, most famous being the Carinthian peasant revolt of 1478, the Slovene peasant revolt of 1515, the Croatian-Slovenian peasant revolt of 1573, the Second Slovene peasant revolt of 1635, and the Tolmin peasant revolt of 1713.

The late 17th century was also marked by a vivid intellectual and artistic activity. Many Italian Baroque artists, mostly architects and musicians, settled in the Slovene Lands, and contributed greatly to the development of the local culture. Artists like Francesco Robba, Andrea Pozzo, Vittore Carpaccio and Giulio Quaglio worked in the Slovenian territory, while scientists such as Johann Weikhard von Valvasor and Johannes Gregorius Thalnitscher contributed to the development of the scholarly activities. By the early 18th century, however, the region entered another period of stagnation, which was slowly overcome only by the mid-18th century.

Age of Enlightenment to the national movement

.jpg)

Between the early 18th century and early 19th century, the Slovene lands experienced a period of peace, with a moderate economic recovery starting from mid-18th century onward. The Adriatic city of Trieste was declared a free port in 1718, boosting the economic activity throughout the western parts of the Slovene Lands. The political, administrative and economic reforms of the Habsburg rulers Maria Theresa of Austria and Joseph II improved the economic situation of the peasantry, and were well received by the emerging bourgeoisie, which was however still weak.

In the late 18th century, a process of standardarization of Slovene language began, promoted by Carniolan clergymen like Marko Pohlin and Jurij Japelj. During the same period, peasant-writers began using and promoting the Slovene vernacular in the countryside. This popular movement, known as bukovniki, started among Carinthian Slovenes as part a wider revival of Slovene literature. The Slovene cultural tradition was strongly reinforced in the Enlightenment period in the 18th century by the endeavours of the Zois Circle. After two centuries of stagnation, Slovene literature emerged again, most notably in the works of the playwright Anton Tomaž Linhart and the poet Valentin Vodnik. However, German remained the main language of culture, administration and education well into the 19th century.

Between 1805 and 1813, the Slovene-settled territory was part of the Illyrian Provinces, an autonomous province of the Napoleonic French Empire, the capital of which was established at Ljubljana. Although the French rule in the Illyrian Provinces was short-lived it significantly contributed to greater national self-confidence and awareness of freedoms. The French did not entirely abolish the feudal system, their rule familiarised in more detail the inhabitants of the Illyrian Provinces with the achievements of the French revolution and with contemporary bourgeois society. They introduced equality before the law, compulsory military service and a uniform tax system, and also abolished certain tax privileges, introduced modern administration, separated powers between the state and the Church, and nationalised the judiciary.

In August 1813, Austria declared war on France. Austrian troops led by General Franz Tomassich invaded the Illyrian Provinces. After this short French interim all Slovene Lands were, once again, included in the Austrian Empire. Slowly, a distinct Slovene national consciousness developed, and the quest for a political unification of all Slovenes became widespread. In the 1820s and 1840s, the interest in Slovene language and folklore grew enormously, with numerous philologists collecting folk songs and advancing the first steps towards a standardization of the language. A small number of Slovene activist, mostly from Styria and Carinthia, embraced the Illyrian movement that started in neighboring Croatia and aimed at uniting all South Slavic peoples. Pan-Slavic and Austro-Slavic ideas also gained importance. However, the intellectual circle around the philologist Matija Čop and the Romantic poet France Prešeren was influential in affirming the idea of Slovene linguistic and cultural individuality, refusing the idea of merging the Slovenes into a wider Slavic nation.

In 1848, a mass political and popular movement for the United Slovenia (Zedinjena Slovenija) emerged as part of the Spring of Nations movement within the Austrian Empire. Slovene activists demanded a unification of all Slovene-speaking territories in a unified and autonomous Slovene kingdom within the Austrian Empire. Although the project failed, it served as an almost undisputed platform of Slovene political activity in the following decades.

Clashing nationalisms in the late 19th century

%2C_dve_prvi_premi%2C_zadnja_za_regiranje._V_krclu_zasajeni_%22piki%22_1960_(3).jpg)

Between 1848 and 1918, numerous institutions (including theatres and publishing houses, as well as political, financial and cultural organisations) were founded in the so-called Slovene National Awakening. Despite their political and institutional fragmentation and lack of proper political representation, the Slovenes were able to establish a functioning national infrastructure.

With the introduction of a constitution granting civil and political liberties in the Austrian Empire in 1860, the Slovene national movement gained force. Despite its internal differentiation among the conservative Old Slovenes and the progressive Young Slovenes, the Slovene nationals defended similar programs, calling for a cultural and political autonomy of the Slovene people. In the late 1860s and early 1870s, a series of mass rallies called tabori, modeled on the Irish monster meetings, were organized in support of the United Slovenia program. These rallies, attended by thousands of people, proved the allegiance of wider strata of the Slovene population to the ideas of national emancipation.

By the end of the 19th century, Slovenes had established a standardized literary language, and a thriving civil society. Literacy levels were among the highest in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and numerous national associations were present at grassroots level.[5] The idea of a common political entity of all South Slavs, known as Yugoslavia, emerged.[6]

Since the 1880s, a fierce culture war between Catholic traditionalists and integralists on one side, and liberals, progressivists and anticlericals dominated Slovene political and public life, especially in Carniola. During the same period, the growth of industrialization intensified social tensions. Both Socialist and Christian socialist movements mobilized the masses. In 1905, the first Socialist mayor in the Austro-Hungarian Empire was elected in the Slovene mining town of Idrija on the list of the Yugoslav Social Democratic Party. In the same years, the Christian socialist activist Janez Evangelist Krek organized hundreds of workers and agricultural cooperatives throughout the Slovene countryside.

At the turn of the 20th century, national struggles in ethnically mixed areas (especially in Carinthia, Trieste and in Lower Styrian towns) dominated the political and social lives of the citizenry. By the 1910s, the national struggles between Slovene and Italian speakers in the Austrian Littoral, and Slovene and German speakers, overshadowed other political conflicts and brought about a nationalist radicalization on both sides.

In the last two decades before World War One, Slovene arts and literature experienced one of its most flourishing periods, with numerous talented modernist authors, painters and architects.[7] The most important authors of this period were Ivan Cankar, Oton Župančič and Dragotin Kette, while Ivan Grohar and Rihard Jakopič were among the most talented Slovene visual artists of the time.

After the Ljubljana earthquake of 1895, the city experienced a rapid modernization under the charismatic Liberal nationalist mayors Ivan Hribar and Ivan Tavčar. Architects like Max Fabiani and Ciril Metod Koch introduced their own version of the Vienna Secession architecture to Ljubljana. In the same period, the Adriatic port of Trieste became an increasingly important center of Slovene economy, culture and politics. By 1910, around a third of the city population was Slovene, and the number of Slovenes in Trieste was higher than in Ljubljana.[8]

At the turn of the 20th century, hundreds of thousands of Slovenes emigrated to other countries, mostly to the United States, but also to South America, Germany,[9] Egypt[10] and to larger cities in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, especially Zagreb and Vienna. It has been calculated that around 300,000 Slovenes emigrated between 1880 and 1910, which means that one in six Slovenes left their homeland. Such disproportionally high emigration rates resulted in a relatively small population growth in the Slovene Lands. Comparatively to other Central European regions, the Slovene Lands lost demographic weight between the late 18th and early 20th century.

Emigration

The period between the 1880s and World War I saw a mass emigration from the present-day Slovenia to America. The largest group of Slovenes eventually settled in Cleveland, Ohio, and the surrounding area. The second-largest group settled in Chicago, principally on the Lower West Side. Many Slovene immigrants went to southwestern Pennsylvania, southeastern Ohio and the state of West Virginia to work in the coal mines and lumber industry. Some also went to the Pittsburgh or Youngstown, Ohio areas, to work in the steel mills, as well as Minnesota's Iron Range, to work in the iron mines.

World War One

World War I resulted in heavy casualties for Slovenia, particularly on the bloody Soča front in Slovenia's western border area. Hundreds of thousands of Slovene conscripts were drafted in the Austro-Hungarian Army, and over 30,000 of them lost their lives during the World War I. Hundreds of thousands of Slovenes were resettled in refugee camps in Italy and Austria. Ethnic Slovenes in refugees camps led by Italy, however, were treated as state enemies, and several thousands died of malnutrition and diseases between 1915 and 1918.[11] Entire areas of the Slovenian Littoral were destroyed.

After the outbreak of World War I, the Austrian Parliament was dissolved and civil liberties suspended. Many Slovene political activists, especially in Carniola and Styria, were imprisoned by Austro-Hungarian authorities on charges of pro-Serbian or pan-Slavic sympathies. 469 Slovenes were executed on charges of treason in the first year of the war alone, provoking a strong anti-Austrian resentment among the national-minded strata of the Slovene population. Hundreds of thousands of Slovene conscripts were drafted in the Austro-Hungarian Army, and over 30,000 of them lost their lives in the course of the war.

The Italian Royal Army launched an attack on Austria-Hungary in 1915 on territory populated by Slovenes. Some of the fiercest battles were fought along the Soča (Isonzo) river and on the Kras (Carso) plateau in what is now western Slovenia.

Merging into the Yugoslav state and struggle for the border areas

The Slovene People's Party launched a movement for self-determination, demanding the creation of a semi-independent South Slavic state under Habsburg rule. The proposal was picked up by most Slovene parties, and a mass mobilization of Slovene civil society, known as the Declaration Movement, followed. By early 1918, more than 200,000 signatures were collected in favor of the Slovene People Party's proposal.[12]

During the War, some 500 Slovenes served as volunteers in the Serbian army, while a smaller group led by Captain Ljudevit Pivko, served as volunteers in the Italian Army. In the final year of the war, many predominantly Slovene regiments in the Austro-Hungarian Army staged a mutiny against their military leadership; the most famous mutiny of Slovene soldiers was the Judenburg Rebellion in May 1918.[13]

Following the dissolution of Austro-Hungarian Empire in the aftermath of the World War I, a National Council of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs took power in Zagreb on 6 October 1918. On 29 October independence was declared by a national gathering in Ljubljana, and by the Croatian parliament, declaring the establishment of the new State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. On 1 December 1918 the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs merged with Serbia, becoming part of the new Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, itself being renamed in 1929 to Kingdom of Yugoslavia.

Slovenes whose territory fell under the rule of neighboring states Italy, Austria and Hungary, were subjected to policies of assimilation.

Border with Austria

After the dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in late 1918, an armed dispute started between the Slovenes and German Austria for the regions of Lower Styria and southern Carinthia. In November 1918, Rudolf Maister seized the city of Maribor and surrounding areas of Lower Styria in the name of the newly formed Yugoslav state. Around the same time a group of volunteers led by Franjo Malgaj attempted to take control of southern Carinthia. Fighting in Carinthia lasted between December 1918 and June 1919, when the Slovene volunteers and the regular Serbian Army managed to occupy the city of Klagenfurt.

In compliance with the Treaty of Saint-Germain, the Yugoslav forces had to withdraw from Klagenfurt, while a referendum was to be held in other areas of southern Carinthia. In October 1920, the majority of the population of southern Carinthia voted to remain in Austria, and only a small portion of the province (around Dravograd and Guštanj) was awarded to the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. With the Treaty of Trianon, on the other hand, Kingdom of Yugoslavia was awarded the Slovene-inhabited Prekmurje region, which had belonged to Hungary since the 10th century.

Border with Italy

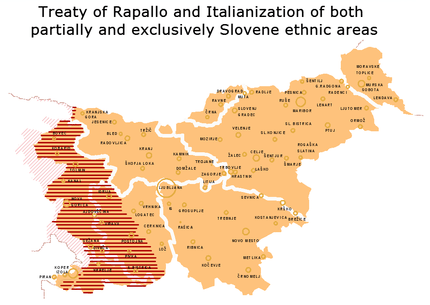

In exchange for joining the Allied Powers in the First World War, the Kingdom of Italy, under the secret Treaty of London (1915) and later Treaty of Rapallo (1920), was granted rule over much of the Slovene territories. These included a quarter of the Slovene ethnic territory, including areas that were exclusively ethnic Slovene. The population of the affected areas was approximately 327,000[14] of the total population of 1.3 million Slovenes.[15]

Kingdom of Yugoslavia

In 1921, against the vote of the great majority (70%) of Slovene MPs a centralist constitution was passed in the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes. Despite it, Slovenes managed to maintain a high level of cultural autonomy, and both economy and the arts prospered. Slovene politicians participated in almost all Yugoslav governments, and the Slovene conservative leader Anton Korošec briefly served as the only non-Serbian Prime Minister of Yugoslavia in the period between the two world wars.

In 1929, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes was renamed to Kingdom of Yugoslavia. The constitution was abolished, civil liberties suspended, while the centralist pressure intensified. Slovenia was renamed to Drava Banovina. During the whole interwar period, Slovene voters strongly supported the conservative Slovene People's Party, which unsuccessfully fought for the autonomy of Slovenia within a federalized Yugoslavia. In 1935, however, the Slovene People's Party joined the pro-regime Yugoslav Radical Community, opening the space for the development of a left wing autonomist movement. In the 1930s, the economic crisis created a fertile ground for the rising of both leftist and rightist radicalisms. In 1937, the Communist Party of Slovenia was founded as an autonomous party within the Communist Party of Yugoslavia. Between 1938 and 1941, left liberal, Christian left and agrarian forces established close relations with members of the illegal Communist party, aiming at establishing a broad anti-Fascist coalition.

The main territory of Slovenia, being the most industrialized and westernized among others less developed parts of Yugoslavia became the main center of industrial production: in comparison to Serbia, for example, in Slovenia the industrial production was four times greater and even twenty-two times greater than in Yugoslav Macedonia. The interwar period brought a further industrialization in Slovenia, with a rapid economic growth in the 1920s followed by a relatively successful economic adjustment to the 1929 economic crisis.

The interwar period brought a further industrialization in Slovenia, with a rapid economic growth in the 1920s followed by a relatively successful economic adjustment to the 1929 economic crisis. This development however affected only certain areas, especially the Ljubljana Basin, the Zasavje region, parts of Slovenian Carinthia, and the urban areas around Celje and Maribor. Tourism experienced a period of great expansion, with resort areas like Bled and Rogaška Slatina gaining an international reputation. Elsewhere, agriculture and forestry remained the predominant economic activities. Nevertheless, Slovenia emerged as one of the most prosperous and economically dynamic areas in Yugoslavia, profiting from a large Balkanic market. Arts and literature also prospered, as did architecture. The two largest Slovenian cities, Ljubljana and Maribor, underwent an extensive program of urban renewal and modernization. Architects like Jože Plečnik, Ivan Vurnik and Vladimir Šubic introduced modernist architecture to Slovenia.

Fascist Italianization of Littoral Slovenes and resistance

Not only partially, but also exclusively ethnic Slovene territories that included a quarter of Slovene ethnic territory and approximately 327.000 out of total population of 1.3[14] million Slovenes, were annexed by Kingdom of Italy according to secret Treaty of London and Treaty of Rapallo (1920) as reward for changing sides in the First World War.[15] The treaty left half a million Slavs (besides Slovenes also Croatians) inside Italy, while only a few hundred Italians in the fledgling Yugoslav (i.e. Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes renamed "Yugoslavia" in 1929) state".[16]

Trieste was at the end of 19th century de facto the largest Slovene city, having had more Slovene inhabitants than even Ljubljana. After being ceded from the multi-ethnic Austria, Italian lower middle class — who felt most threatened by the city's Slovene middle class — sought to make Trieste "città italianissima", committing series of attacks, led by Black Shirts, on Slovene shops, libraries, lawyer offices, and the central place of the rival community in Narodni dom.[17] Forced Italianization followed and by the mid-1930s, several thousand Slovenes, especially intellectuals from Trieste region, emigrated to the Kingdom of Yugoslavia and to South America.

The present-day Slovenian municipalities of Idrija, Ajdovščina, Vipava, Kanal, Postojna, Pivka, and Ilirska Bistrica, were subjected to forced Italianization. The Slovene minority in Italy (1920-1947) lacked any minority protection under international or domestic law.[18] Clashes between the Italian authorities and Fascist squads on one side, and the local Slovene population on the other, started as early as 1920, culminating with the burning of the Narodni dom, the Slovenian National Hall of Trieste. After all Slovene minority organizations in Italy had been suppressed, the militant anti-fascist organization TIGR was formed in 1927 in order to fight Fascist violence. The anti-Fascist guerrilla movement continued throughout the late 1920s and 1930s.

World War II

| During WWII, Nazi Germany and Hungary occupied northern areas (brown and dark green areas, respectively), while Fascist Italy occupied the vertically hashed black area, including Gottschee area. (Solid black western part being annexed by Italy already with the Treaty of Rapallo). After 1943, Germany took over the Italian occupational area, as well. |

Slovenia was the only present-day European nation and the only part of Yugoslavia that was completely absorbed and annexed into neighboring Nazi Germany, Fascist Italy, and Hungary during World War II.[19]

Germany and Hungary occupied northern Slovenia after Axis Powers invaded Yugoslavia on 6 April 1941. The ethnic German Gottscheers were moved out of the province, because Hitler opposed having them in the Italian occupation zone.

On 27 April 1941 in the Province of Ljubljana, occupied by Fascist Italy, the National Liberation Front was organized to carry out a liberation struggle, forming the Slovene Partisans and creating structures of a future state in liberated areas. The Province of Ljubljana saw the deportation of 25.000 people, which equaled 7.5% of the total population. The operation, one of the most drastic in the Europe, filled up many Italian concentration camps, such as Rab, Gonars, Monigo, Renicci di Anghiari and elsewhere.

Slovenes were transported to several camps in Saxony, where they were forced to work on German farms or in factories run by German industries from 1941–1945. The forced labourers were not always kept in formal concentration camps, but often just vacant buildings where they slept until the next day's labour. Toward the end of the war, these camps were liberated by American and Soviet Army troops. Repatriated refugees returned to Yugoslavia to find their homes in shambles.

Some Slovenes collaborated with the occupying powers. The German-sponsored Slovene Home Guard had 21,000 members at the peak of its power. More than 30,000 partisans died fighting Axis forces and their collaborators; during WWII, approximately 8 percent of Slovenes died.

In 1945, Yugoslavia liberated itself and shortly thereafter became a nominally federal Communist state. Slovenia joined the federation as a socialist republic; its own Communist Party was formed in 1937.

At the end of the WW II, Yugoslavia, Greece and Ethiopia requested the extradition of a number of suspects on the list of Italian war criminals. These suspects never saw anything like Nuremberg trials. The British government, at the beginning of the Cold War, saw in Pietro Badoglio, one of these suspects, a guarantee of an anti-communist post-war Italy.[20][21] The survivors received no compensation from the Italian state after the war. Both states tactically "exchanged" the impunity of the Italians accused by Yugoslavia for the renunciation to investigate the foibe and avoid investigations and responsibility on their part. So both Italian, Allied and Yugoslav war and post-war mass killings were forgotten in order to maintain a "good neighbour" policy and good relations.[22][23]

Due to the Communist violence towards the opponents of the Liberation Front as well as anti-revolutionary sentiments, some of the residents of cities as well as clericals and major farmers formed several anti-communist groups that collaborated with the occupying forces. After 1942, the situation in the Slovene Lands has been characterised as a civil war. After the war, large ideologically and ethnically motivated massacres took place.

Excluding Slovenes under Italian rule, between 20,000 and 25,000 Slovenes were killed by Nazis or Italian Fascists, counting only civilian victims.[24] The overall number of Slovene civilians killed by the Nazis, Italian Fascists and their allies is estimated at around 33,000 - this number does not include killed prisoners of war.[24] The majority of these victims were from the German occupied territories Lower Styria, Upper Carniola, Zasavje, and Slovenian Carinthia, soon annexed to the Third Reich.[25] An indeterminate number of Italians and anti-Communist Yugoslavs were killed in the foibe massacres.

Slovenia in Titoist Yugoslavia

Following the re-establishment of Yugoslavia at the end of World War II, Slovenia became part of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, declared on 29 November 1943. A socialist state was established, but because of the Tito-Stalin split, economic and personal freedoms were broader than in the Eastern Bloc. In 1947, Italy ceded most of the Julian March to Yugoslavia, and Slovenia thus regained the Slovenian Littoral. The towns of Koper, Izola, and Piran, Italian-populated urban enclaves saw mass ethnic Italian and anti-Communist emigration (part of the Istrian Exodus) due to the ongoing foibe massacres and other revenge against them for Italian war crimes and due to their fear of Communism, which by 1947 had nationalised all private property.

The dispute over the port of Trieste however remained opened until 1954, until the short-lived Free Territory of Trieste was divided among Italy and Yugoslavia, thus giving Slovenia access to the sea. This division was ratified only in 1975 with the Treaty of Osimo, which gave a final legal sanction to Slovenia's long disputed western border. From the 1950s, the Socialist Republic of Slovenia enjoyed a relatively wide autonomy.

Stalinist period

Between 1945 and 1948, a wave of political repressions took place in Slovenia and in Yugoslavia. Thousands of people were imprisoned for their political beliefs. Several tens of thousands of Slovenes left Slovenia immediately after the war in fear of Communist persecution. Many of them settled in Argentina, which became the core of Slovenian anti-Communist emigration. More than 50,000 more followed in the next decade, frequently for economic reasons, as well as political ones. These later waves of Slovene immigrants mostly settled in Canada and in Australia, but also in other western countries.

The 1948 Tito–Stalin split and aftermath

In 1948, the Tito-Stalin split took place. In the first years following the split, the political repression worsened, as it extended to Communists accused of Stalinism. Hundreds of Slovenes were imprisoned in the concentration camp of Goli Otok, together with thousands of people of other nationalities. Among the show trials that took place in Slovenia between 1945 and 1950, the most important were the Nagode Trial against democratic intellectuals and left liberal activists (1946) and the Dachau trials (1947–1949), where former inmates of Nazi concentration camps were accused of collaboration with the Nazis. Many members of the Roman Catholic clergy suffered persecution. The case of bishop of Ljubljana Anton Vovk, who was doused with gasoline and set on fire by Communist activists during a pastoral visit to Novo Mesto in January 1952, echoed in the western press.

Between 1949 and 1953, a forced collectivization was attempted. After its failure, a policy of gradual liberalization was followed.

1950s: heavy industrialization

In the late 1950s, Slovenia was the first of the Yugoslav republics to begin a process of relative pluralization. A decade of industrialisation was accompanied also by a fervent cultural and literary production with many tensions between the regime and the dissident intellectuals. From the late 1950s onward, dissident circles started to be formed, mostly around short-lived independent journals, such as Revija 57 (1957–1958), which was the first independent intellectual journal in Yugoslavia and one of the first of this kind in the Communist bloc,[26] and Perspektive (1960–1964). Among the most important critical public intellectuals in this period were the sociologist Jože Pučnik, the poet Edvard Kocbek, and the literary historian Dušan Pirjevec.

1960s: "Self-management"

By the late 1960s, the reformist faction gained control of the Slovenian Communist Party, launching a series of reforms, aiming at the modernization of Slovenian society and economy. A new economic policy, known as workers self-management started to be implemented under the advice and supervision of the main theorist of the Yugoslav Communist Party, the Slovene Edvard Kardelj.

1970s: "Years of Lead"

In 1973, this trend was stopped by the conservative faction of the Slovenian Communist Party, backed by the Yugoslav Federal government. A period known as the "Years of Lead" (Slovene: svinčena leta) followed.

1980s: Towards independence

In the 1980s, Slovenia experienced a rise of cultural pluralism. Numerous grass-roots political, artistic and intellectual movements emerged, including the Neue Slowenische Kunst, the Ljubljana school of psychoanalysis, and the Nova revija intellectual circle. By the mid-1980s, a reformist fraction, led by Milan Kučan, took control of the Slovenian Communist Party, starting a gradual reform towards a market socialism and controlled political pluralism.

The Yugoslav economic crisis of the 1980s increased the struggles within the Yugoslav Communist regime regarding the appropriate economic measures to be undertaken. Slovenia, which had less than 10% of overall Yugoslav population, produced around a fifth of the country's GDP and a fourth of all Yugoslav exports. The political disputes around economic measures was echoed in the public sentiment, as many Slovenes felt they were being economically exploited, having to sustain an expensive and inefficient federal administration.

In 1987 and 1988, a series of clashes between the emerging civil society and the Communist regime culminated with the Slovene Spring. In 1987, a group of liberal intellectuals published a manifesto in the alternative Nova revija journal; in their so-called Contributions for the Slovenian National Program, they called for democratization and a greater independence for Slovenia. Some of the articles openly contemplated Slovenia's independence from Yugoslavia and the establishment of a full-fedged parliamentary democracy. The manifesto was condemned by the Communist authorities, but the authors did not suffer any direct repression, and the journal was not suppressed (although the editorial board was forced to resign). At the end of the same year, a massive strike broke out in the Litostroj manufacturing plant in Ljubljana, which led to the establishment of the first independent trade union in Yugoslavia. The leaders of the strike established an independent political organization, called the Social Democratic Union of Slovenia. Soon afterwards, in mid May 1988, an independent Peasant Union of Slovenia was organized. Later in the same month, the Yugoslav Army arrested four Slovenian journalists of the alternative magazine Mladina, accusing them of revealing state secrets. The so-called Ljubljana trial triggered mass protests in Ljubljana and other Slovenian cities.

A mass democratic movement, coordinated by the Committee for the Defense of Human Rights, pushed the Communists in the direction of democratic reforms. These revolutionary events in Slovenia pre-dated by almost one year the Revolutions of 1989 in Eastern Europe, but went largely unnoticed by international observers.

At the same time, the confrontation between the Slovenian Communists and the Serbian Communist Party, dominated by the charismatic nationalist leader Slobodan Milošević, became the most important political struggle in Yugoslavia. The poor economic performance of the Federation, and rising clashes between the different republics, created a fertile soil for the rise of secessionist ideas among Slovenes, both anti-Communists and Communists. On 27 of September 1989 the Slovenian Assembly made many amendments to the 1974 constitution including the abandonment of the League of Communists of Slovenia monopoly on political power and the right of Slovenia to leave Yugoslavia.[27]

In an action named "Action North" in 1989, Slovene police forces, members of which later organized their own veteran organization, prevented several hundred Milošević's supporters to meet in Ljubljana on 1 December, on a so-called Rally of Truth, with an attempt to overthrow Slovenian leadership because of its opposition to Serb centralist policy. The action can be considered the first defense action for Slovenian independence.[28][29][30]

On 23 January 1990, the League of Communists of Slovenia, in protest against the domination of the Serb nationalist leadership, walked out of the 14th Congress of the League of Communists of Yugoslavia which effectively ceased to exist as a national party - they were followed soon after by the League of Communists of Croatia.

In September 1989, numerous constitutional amendments were passed by the Assembly, which introduced parliamentary democracy to Slovenia.[31][32] On 7 March 1990, the Slovenian Assembly passed the amendment XCI changing the official name of the state to the Republic of Slovenia dropping the word 'Socialist'. The new name has been official since 8 March 1990.[33][34]

Republic of Slovenia

Free elections

On 30 December 1989 Slovenia officially opened the spring 1990 elections to opposition parties thus inaugurating multi-party democracy. The Democratic Opposition of Slovenia (DEMOS) coalition of democratic political parties was created by an agreement between the Slovenian Democratic Union, the Social Democrat Alliance of Slovenia, the Slovene Christian Democrats, the Farmers' Alliance and the Greens of Slovenia. The leader of the coalition was the famous dissident Jože Pučnik.

On 8 April 1990, the first free multiparty parliamentary elections, and the first round of the Presidential elections, were held. DEMOS defeated the former Communist party in the parliamentary elections, by gathering 54% of the votes.[33] A coalition government led by the Christian Democrat Lojze Peterle was formed, and began economic and political reforms that established a market economy and a liberal democratic political system. At the same time, the government pursued the independence of Slovenia from Yugoslavia.

Milan Kučan was elected President in the second round of the Presidential elections on 22 Apr 1990, defeating the DEMOS candidate Jože Pučnik.

Kučan presidency (1990–2002)

The DEMOS government (1990–1992): Independence

Milan Kučan strongly opposed the preservation of Yugoslavia through violent means. After the concept of a loose confederation failed to gain support by the republics of Yugoslavia, Kučan favoured a controlled process of non-violent disassociation that would enable the collaboration of the former Yugoslav nations on a new, different basis.

On 23 December 1990, a referendum on the independence of Slovenia was held, in which the more than 88% of Slovenian residents voted for the independence of Slovenia from Yugoslavia. Slovenia became independent through the passage of the appropriate acts on 25 June 1991.[35][36] In the morning of the next day, a short Ten-Day War began, in which the Slovenian forces successfully rejected Yugoslav military interference.[35][37] In the evening, the independence was solemnly proclaimed in Ljubljana by the Speaker of the Parliament France Bučar. The Ten-Day War lasted till 7 July 1991,[37] when the Brijuni Agreement was made, with the European Community as a mediator, and the Yugoslav National Army started its withdrawal from Slovenia. On 26 October 1991, the last Yugoslav soldier left Slovenia.[37]

On 23 December 1991 the Assembly of the Republic of Slovenia passed a new Constitution, which became the first Constitution of independent Slovenia.[38]

Kučan represented Slovenia at the peace conference on former Yugoslavia in the Hague and Brussels which concluded that the former Yugoslav nations were free to determine their future as independent states. On May 22, 1992 Kučan represented Slovenia as it became a new member of the United Nations.

The most important achievement of the Coalition, however, was the declaration of independence of Slovenia on 25 June 1991, followed by a Ten-Day War in which the Slovenians rejected Yugoslav military interference. As a result of internal disagreements the coalition fell apart in 1992. It was officially dissolved in April 1992 in agreement with all the parties that had composed it. Following the collapse of Lojze Peterle's government, a new coalition government, led by Janez Drnovšek was formed, which included several parties of the former DEMOS. Jože Pučnik became vice-president in Drnovšek's cabinet, guaranteeing some continuity in the government policies.

The first country to recognise Slovenia as an independent country was Croatia on 26 June 1991. In the second half of 1991, some of the countries formed after the collapse of the Soviet Union recognized Slovenia. These were the Baltic countries Lithuania, Latvia, and Estonia, and Georgia, Ukraine, and Belarus. On 19 December 1991, Iceland and Sweden recognised Slovenia, and Germany passed a resolution on the recognition of Slovenia, realised alongside the European Economic Community (EEC) on 15 January 1992. On 13, respectively 14 January 1992, the Holy See and San Marino recognised Slovenia. The first transmarine countries to recognise Slovenia were Canada and Australia on the 15, respectively 16 January 1992. The United States was at first very reserved towards the Slovenian independence and recognised Slovenia only on 7 April 1992.

The recognition by the EEC was particularly significant for Slovenia, as in December 1991 the ECC passed criteria for the international recognition of newly founded countries, which included democracy, the respect for human rights, the government of law, and the respect for the national minority rights. The recognition of Slovenia therefore indirectly also meant that Slovenia had been meeting the passed criteria.[39]

In December 1992, after the independence and the international recognition of Slovenia, Kučan was elected as the first President of Slovenia in the 1992 presidential election, with the support of the citizens list. He won another five-year term in the 1997 election, running again as an independent and again winning the majority in the first round.

Drnovšek premiership (1992–2002): Re-orientation of Slovenia's trade

Drnovšek was the second Prime Minister of independent Slovenia. He was chosen as a compromise candidate and an expert in economic policy, transcending ideological and programmatic divisions between parties. Drnovšek's governments reoriented Slovenia's trade away from Yugoslavia towards the West and contrary to some other former Communist countries in Eastern Europe, the economic and social transformation followed a gradualist approach.[40] After six months in opposition from May 2000 to Autumn 2000, Drnovšek returned to power again and helped to arrange the first meeting between George W. Bush and Vladimir Putin (Bush-Putin 2001).

Drnovšek presidency (2002–2007); EU and NATO membership

Drnovšek held the position of the President of Republic from 2002 to 2007. During the term, in March 2003, Slovenia held two referendums on joining the EU and NATO. Slovenia joined NATO on 29 March 2004 and the European Union on 1 May 2004.

Janša premiership (2004–2008): Unsustainable growth

Janez Janša was Prime Minister of Slovenia from November 2004 to November 2008 for the first time. During the term characterized by over-enthusiasm after joining EU, between 2005 and 2008 the Slovenian banks have seen loan-deposit ratio veering out of control, over-borrowing from foreign banks and then over-crediting private sector, leading to its unsustainable growth.

Türk presidency (2007–2012)

Danilo Türk held the position of the President of Republic from 2007 to 2012.

Pahor premiership (2008–2012): Blocked reforms

Borut Pahor was Prime Minister of Slovenia from November 2008 until February 2012. Faced by the global economic crisis his government proposed economic reforms, but they were rejected by the opposition leader Janez Janša and blocked by referenda in 2011.[41] On the other hand, the voters voted in favour of an arbitration agreement with Croatia, aimed to solve the border dispute between the countries, emerging after the breakup of Yugoslavia.[41]

Pahor Presidency (2012)

Pahor has held the position of president since 2012.

Janša premiership (2012–2013): Anti-corruption report

Janša was Prime Minister of Slovenia from February 2012 until March 2013 for the second time. He was replaced by the first woman PM in history of Slovenia, Alenka Bratušek, after the official anti-corruption agency's Report on the Parliamentary Parties' Leaders was issued.[42][43][44]

See also

- Breakup of Yugoslavia

- Divje Babe flute

- Habsburg Monarchy

- History of the Balkans

- History of Europe

- History of Austria, History of Italy, History of Hungary, History of Croatia, History of Yugoslavia

- History of the Jews in Slovenia

- League of Communists of Yugoslavia

- List of Presidents of Slovenia

- List of heads of state of Yugoslavia

- List of Prime Ministers of Yugoslavia

- Politics of Slovenia

- Prime Minister of Slovenia

- Ten-Day War

- Timeline of Slovenian history

- Republic of Prekmurje

- Slovene March (Kingdom of Hungary)

References

- ↑ Debeljak, Irena; Turk, Matija. "Potočka zijalka". In Šmid Hribar, Mateja. Torkar, Gregor. Golež, Mateja. Podjed, Dan. Drago Kladnik, Drago. Erhartič, Bojan. Pavlin, Primož. Jerele, Ines. Enciklopedija naravne in kulturne dediščine na Slovenskem – DEDI (in Slovenian). Retrieved 12 March 2012.

- ↑ "Application for the Title of the European Capital of Culture 2012" (PDF). City Municipality of Maribor. 2008.

- ↑ Edo Škulj, ed., Trubarjev simpozij (Rome – Celje – Ljubljana: Celjska Mohorjeva družba, Društvo Mohorjeva družba, Slovenska teološka akademija, Inštitut za zgodovino Cerkve pri Teološki fakulteti, 2009).

- ↑ Spezialortsrepertorium der Oesterreichischen Laender. VII. Oesterreichisch-Illyrisches Kuestenland. Wien, 1918, Verlag der K.K. Hof- und Staatsdruckerei

- ↑ Bojan Balkovec et al. eds, Slovenska kronika XX stoletja, vol. 1 (Ljubljana: Nova revija, 1995)

- ↑ Lojze Ude, Slovenci in jugoslovanska skupnost (Maribor: Obzorja, 1972).

- ↑ Dušan Pirjevec, Ivan Cankar in evropska literatura (Ljubljana: Cankarjeva založba, 1964)

- ↑ Boris M. Gombač, Trst-Trieste – dve imeni, ena identiteta (Ljubljana-Trieste: Narodni muzej, tržaška založba, 1993).

- ↑ Božidar Tensundern, Vestfalski Slovenci (Klagenfurt: Družba svetega Mohorja, 1973)

- ↑ Arctur d.o.o. "aleksandrinke".

- ↑ Petra Svoljšak, Slovenski begunci v Italiji med prvo svetovno vojno (Ljubljana 1991).

- ↑ Kranjec, Silvo (1925–1991). "Korošec Anton". Slovenski biografski leksikon (in Slovenian) (Online ed.). Slovenian Academy of Sciences and Arts. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- ↑ Švajncer, Janez J. "Military history of Slovenians" (PDF). The Slovenian. Retrieved 17 October 2010.

- 1 2 3 Lipušček, U. (2012) Sacro egoismo: Slovenci v krempljih tajnega londonskega pakta 1915, Cankarjeva založba, Ljubljana. ISBN 978-961-231-871-0

- 1 2 3 Cresciani, Gianfranco (2004). "Clash of civilisations", Italian Historical Society Journal, Vol. 12, No. 2, p. 4

- ↑ Hehn, Paul N. (2005) A Low Dishonest Decade: Italy, the Powers and Eastern Europe, 1918-1939., Chapter 2, Mussolini, Prisoner of the Mediterranean

- ↑ Morton, Graeme; R. J. Morris; B. M. A. de Vries (2006).Civil Society, Associations, and Urban Places: Class, Nation, and Culture in Nineteenth-century Europe, Ashgate Publishing, UK

- ↑ Hehn, Paul N. (2005). A Low Dishonest Decade: The Great Powers, Eastern Europe, and the Economic Origins of World War II, 1930–1941. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 44–45. ISBN 0-8264-1761-2.

- ↑ Gregor Joseph Kranjc (2013).To Walk with the Devil, University of Toronto Press, Scholarly Publishing Division, p. introduction 5

- ↑ Italy's bloody secret (Archived by WebCite®), written by Rory Carroll, Education, The Guardian, June 2001

- ↑ Effie Pedaliu (2004) Britain and the 'Hand-over' of Italian War Criminals to Yugoslavia, 1945-48. Journal of Contemporary History. Vol. 39, No. 4, Special Issue: Collective Memory, pp. 503-529 (JStor.org preview)

- ↑ Marco Ottanelli. "La verità sulle foibe" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2007-12-17. Retrieved 2006-06-03.

- ↑ Crimini di Guerra. "La mancata estradizione e l'impunità dei presunti criminali di guerra italiani accusati per stragi in Africa e in Europa" (in Italian). Archived from the original on 2006-09-02. Retrieved 2006-06-03.

- 1 2 http://www.ds-rs.si/dokumenti/publikacije/Zbornik_05-1.pdf

- ↑ "Vlačič: Kar se je zgodilo vam, se ne sme zgoditi nikomur". Prvi interaktivni multimedijski portal, MMC RTV Slovenija.

- ↑ Taras Kermauner, Slovensko perspektivovstvo (Znanstveno in publicistično središče, 1996).

- ↑ "Year 1989 - Slovenia 20 years".

- ↑ "Historical Circumstances in Which "The Rally of Truth" in Ljubljana Was Prevented". Journal of Criminal Justice and Security. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ↑ ""Rally of truth" (Miting resnice)". A documentary published by RTV Slovenija. Retrieved 4 July 2012.

- ↑ "akcijasever.si". The "North" Veteran Organization. Retrieved 3 July 2012.

- ↑ Zajc, Drago (2004). Razvoj parlamentarizma: funkcije sodobnih parlamentov [The Development of Parliamentarism: The Functions of Modern Parliaments] (PDF) (in Slovenian). Publishing House of the Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana. p. 109. ISBN 961-235-170-8.

- ↑ "Osamosvojitveni akti Republike Slovenije" [Independence Acts of the Republic of Slovenia] (in Slovenian). Office for Legislation, Government of the Republic of Slovenia. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- 1 2 "Year 1990 - Slovenia 20 years".

- ↑ "Odlok o razglasitvi ustavnih amandmajev k ustave Socialistične Republike Slovenije" [The Decree About the Proclamation of Constitutional Amendments to the Constitution of the Socialist Republic of Slovenia] (PDF). Uradni list Republike Slovenije (in Slovenian). 16 March 1990. Retrieved 27 December 2011.

- 1 2 Race, Helena (2005). "Dan prej" - 26. junij 1991: diplomsko delo ["A Day Before" – 26 June 1991: Diploma Thesis] (PDF) (in Slovenian). Faculty of Social Sciences, University of Ljubljana. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ↑ Janko Prunk (2001). "Path to Slovene State". Public Relations and Media Office, Government of the Republic of Slovenia. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- 1 2 3 "About the Slovenian Military Forces: History". Slovenian Armed Forces, Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 3 February 2011.

- ↑ "Year 1991 - Slovenia 20 years".

- ↑ "Mineva 20 let od prvih zahodnoevropskih priznanj Slovenije" [It's been 20 year from the first Western-European recognitions] (in Slovenian). Primorske novice. 18 December 2011.

- ↑ "Janez Drnovsek: Slovenian president who achieved membership of the EU and Nato for the former Yugoslav republic" The Independent Feb 25th 2008

- 1 2 "Zgodba o neki levi vladi :: Prvi interaktivni multimedijski portal, MMC RTV Slovenija". Rtvslo.si. Retrieved 23 October 2011.

- ↑ Official News on the Commission's website, 10 January 2013, Ljubljana, Slovenia.

- ↑ Most powerful politicians do not know where they got the money (In Slovene: "Najmočnejša politika ne vesta odkod jima denar"), Delo, 9 January 2013

- ↑ Žerdin, A. (2013)There is no room for an unexplained sources of money in the public servants' budgets (In Slovene: "V bilancah funkcionarjev ni prostora za gotovino neznanega izvora"), Delo

Further reading

- Oto Luthar (ed), The Land Between: A history of Slovenia. With contributions by Oto Luthar, Igor Grdina, Marjeta Šašel Kos, Petra Svoljšak, Peter Kos, Dušan Kos, Peter Štih, Alja Brglez and Martin Pogačar (Frankfurt am Main etc., Peter Lang, 2008).

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Slovenia. |

- Sistory.si - an education and research portal of Slovene historiography.

- History of Slovenia: Primary Documents