Optimism

Optimism is a mental attitude. A common idiom used to illustrate optimism versus pessimism is a glass with water at the halfway point, where the optimist is said to see the glass as half full and the pessimist sees the glass as half empty.

The term is originally derived from the Latin optimum, meaning "best". Being optimistic, in the typical sense of the word, is defined as expecting the best possible outcome from any given situation. This is usually referred to in psychology as dispositional optimism. It thus reflects a belief that future conditions will work out for the best.[1]

Theories of optimism include dispositional models, and models of explanatory style. Methods to measure optimism have been developed within both theoretical systems, such as various forms of the Life Orientation Test, for the original definition of optimism, or the Attributional Style Questionnaire designed to test optimism in terms of explanatory style.

Variation in optimism and pessimism is somewhat heritable[2] and reflects biological trait systems to some degree.[3] It is also influenced by environmental factors, including family environment,[2] with some suggesting it can be learned.[4] Optimism may also be linked to health.[5]

Psychological Optimism

Dispositional Optimism

Researchers operationalize the term differently depending on their research. As with any trait characteristic, there are several ways to evaluate optimism, such as the Life Orientation Test (LOT).

Dispositional optimism and pessimism[6] are typically assessed by asking people whether they expect future outcomes to be beneficial or negative (see below). The LOT returns separate optimism and pessimism scores for each individual. Behaviourally, these two scores correlate around r = 0.5. Optimistic scores on this scale predict better outcomes in relationships,[7] higher social status,[8] and reduced loss of well-being following adversity.[9] Health preserving behaviors are associated with optimism while health-damaging behaviors are associated with pessimism.[10]

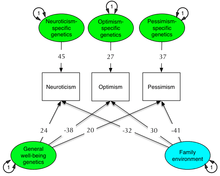

Some have argued that pessimism and optimism are ends of a single dimension, with any distinction between them reflecting factors such as social desirability. Confirmatory modelling, however, supports a two-dimensional model[11] and the two dimensions predict different outcomes.[12] Genetic modelling confirms this independence, showing that pessimism and optimism are inherited as independent traits, with the typical correlation between them emerging as a result of a general well-being factor and family environment influences.[2]

Explanatory style

Explanatory style is distinct from dispositional theories of optimism. While related to life-orientation measures of optimism, attributional style theory suggests that dispositional optimism and pessimism are reflections of the ways in which people explain events, i.e. that attributions cause these dispositions . Measures of attributional style distinguish three dimensions among explanations for events: Whether these explanations draw on internal versus external causes; whether the causes are viewed as stable versus unstable; and whether explanations apply globally versus being situationally specific. In addition, the measures distinguish attributions for positive and for negative events.

An optimistic person is one who attributes internal, stable, and global explanations to good things. Pessimistic explanations are those which attribute these traits of stability, globality and internality to negative events, such as difficulty in relationships.[13] Models of Optimistic and Pessimistic attributions show that attributions themselves are a cognitive style – individuals who tend to focus on the global explanations do so for all types of events, and the styles correlate among each other. In addition to this, individuals vary in how optimistic their attributions are for good events, and on how pessimistic their attributions are for bad events, but these two traits of optimism and pessimism are un-correlated.[14]

There is much debate about the relationship between explanatory style and optimism. Some researchers argue that optimism is simply the lay-term for what researchers know as explanatory style.[15] More commonly, it is found that explanatory style is quite distinct from dispositional optimism,[16][17] and the two should not be used interchangeably as they are marginally correlated at best. More research is required to "bridge" or further differentiate these concepts.[13]

Origins of Optimism

As with all psychological traits, differences in both dispositional optimism and pessimism [2] and in attributional style [18] are heritable Both optimism and pessimism are strongly influenced by environmental factors, including family environment,.[2] It has been suggested that optimism may be indirectly inherited as a reflection of underlying heritable traits such as intelligence, temperament and alcoholism.[18] Many theories assume optimism can be learned,[4] and research supports a modest role of family-environment acting to raise (or lower) optimism and lower (or raise) neuroticism and pessimism.[2]

Work utilising brain imaging and biochemistry suggests that at a biological trait level, optimism and pessimism reflect brain systems specialised for the tasks of processing and incorporating beliefs regarding good and bad information respectively.[3]

Assessment

Life Orientation Test

The Life Orientation Test (LOT) was designed by Scheier and Carver (1985) to assess dispositional optimism – expecting positive or negative outcomes,[13] and is one of the more popular tests of optimism and pessimism. There are eight items and four filler items. Four are positive items (e.g. "In uncertain times, I usually expect the best") and four are negative items e.g. "If something can go wrong for me, it will."[19] The LOT has been revised twice—once by the original creators (LOT-R) and also by Chang, Maydeu-Olivares, and D'Zurilla as the Extended Life Orientation Test (ELOT). The Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R: Scheier, Carver, & Bridges, 1994) consisting of 6 items, each scored on a 5-point scale from “Strongly disagree” to “Strongly agree”[20]

Attributional Style Questionnaire

This Attributional Style Questionnaire (ASQ: Peterson et al. 1982 [21]) is based on the explanatory style model of optimism. Subjects read a list of six positive and negative events (e.g. "you have been looking for a job unsuccessfully for some time"), and are asked to record a possible cause for the event. They then rate whether this is internal or external, stable or changeable, and global or local to the event.[21] There are several modified versions of the ASQ including the Expanded Attributional Style Questionnaire (EASQ), the Content Analysis of Verbatim Explanations (CAVE), and the ASQ designed for testing the optimism of children.[13]

Associations with Health

Optimism and health are correlated moderately.[22] Optimism has been shown to explain between 5–10% of the variation in the likelihood of developing some health conditions (correlation coefficients between .20 and .30),[23] notably including cardiovascular disease,[24][25][26] stroke,[27] and depression.[28][29]

The relationship between optimism and health has also been studied with regards to physical symptoms, coping strategies and negative affect for those suffering from rheumatoid arthritis, asthma, and fibromyalgia.

It has been found that among individuals with these diseases, optimists are not more likely than pessimists to report pain alleviation due to coping strategies, despite differences in psychological well-being between the two groups.[30] A meta-analysis has confirmed the assumption that optimism is related to psychological well-being: “Put simply, optimists emerge from difficult circumstances with less distress than do pessimists.”[31] Furthermore, the correlation appears to be attributable to coping style: “That is, optimists seem intent on facing problems head-on, taking active and constructive steps to solve their problems; pessimists are more likely to abandon their effort to attain their goals.”[31]

Optimists may respond better to stress: pessimists have shown higher levels of cortisol (the “stress hormone”) and trouble regulating cortisol in response to stressors.[32] Another study by Scheier examined the recovery process for a number of patients that had undergone surgery.[33] The study showed that optimism was a strong predictor of the rate of recovery. Optimists achieved faster results in “behavioral milestones” such as sitting in bed, walking around, etc. They also were rated by staff as having a more favorable physical recovery. In a 6-month later follow-up, it was found that optimists were quicker to resume normal activities.

Optimism and Well-being

A number of studies have been done on optimism and psychological well-being. One study conducted by Aspinwall and Taylor (1990) assessed incoming freshmen on a range of personality factors such as optimism, self-esteem, locus of self-control, etc.[33] It was found that freshmen who scored high on optimism before entering college were reported to have lower levels of psychological distress than their more pessimistic peers, while controlling for the other personality factors. Over time, the more optimistic students were less stressed, less lonely, and less depressed than their pessimistic counterparts. Thus, this study suggests a strong link between optimism and psychological well-being.

A recent meta-analysis of optimism supported past findings that optimism is positively correlated with life satisfaction, happiness, psychological and physical well-being and negatively correlated with depression and anxiety.[34]

Seeking explanations of the correlation, researchers find that optimists choose lifestyles which may be healthier, and may influence disease. For example, optimists smoke less, are more physically active, consume more fruit, vegetables and whole-grain bread, are more moderate in their consumption of alcohol.[35]

Translating Association into modifiability

It should be noted that research to date has demonstrated that optimists are less likely to have certain diseases or develop certain diseases over time. By comparison, research has not yet been able to demonstrate the ability to change an individual's level of optimism through psychological intervention, and thereby alter the course of disease or likelihood for development of disease. Though in that same vein, an article by Mayo Clinic argues steps to change self-talk from negative to positive may shift individuals from a negative to a more positive/optimistic outlook.[36] Strategies claimed to be of value include surrounding oneself with positive people, identifying areas of change, practicing positive self-talk, being open to humor, and following a healthy lifestyle.[36]

Philosophical optimism

Distinct from a disposition to believe that things will work out, there is a philosophical idea that, perhaps in ways that may not be fully comprehended, the present moment is in an optimum state. This is referred to as panglossian-ism. This view that all of nature - past, present and future - operates by laws of optimization along the lines of Hamilton's principle in the realm of physics is countered by views such as idealism, realism, and philosophical pessimism. Philosophers often link the concept of optimism with the name of Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, who held that we live in the best of all possible worlds, or that God created a physical universe that applies the laws of physics. This idea was famously mocked by Voltaire in his satirical novel Candide as baseless optimism of the sort exemplified by the beliefs of Pangloss, which are the opposite of his fellow traveller Martin's pessimism and emphasis on free will. The phrase "panglossian pessimism" has been used to describe the pessimistic position that, since this is the best of all possible worlds, it is impossible for anything to get any better.

Paradoxically, philosophical pessimism is perhaps associated with the most optimistic long-term view, because it incorporates change. William Godwin for instance argued that society would eventually reach the state where calm reason would replace all violence and force, that mind could eventually make matter subservient to it, and that intelligence could discover the secret of immortality.

Optimalism

Philosophical optimalism, as defined by Nicholas Rescher, holds that this universe exists because it is better than the alternatives.[37] While this philosophy does not exclude the possibility of a deity, it also doesn't require one, and is compatible with atheism.[38]

Psychological optimalism, as defined by the positive psychologist Tal Ben-Shahar, means willingness to accept failure while remaining confident that success will follow, a positive attitude he contrasts with negative perfectionism.[39] Perfectionism can be defined as a persistent compulsive drive toward unattainable goals and valuation based solely in terms of accomplishment.[40] Perfectionists reject the realities and constraints of human ability. They cannot accept failures, delaying any ambitious and productive behavior in fear of failure again.[41] This neuroticism can even lead to clinical depression and low productivity.[42] As an alternative to negative perfectionism, Ben-Shahar suggests the adoption of optimalism. Optimalism allows for failure in pursuit of a goal, and expects that while the trend of activity will tend towards the positive it is not necessary to always succeed while striving to attain goals. This basis in reality prevents the optimalist from being overwhelmed in the face of failure.[39]

Optimalists accept failures and also learn from them, which encourages further pursuit of achievement.[41] Dr. Tal Ben-Shahar believes that Optimalists and Perfectionists show distinct different motives. Optimalists tend to have more intrinsic, inward desires, with a motivation to learn, while perfectionists are highly motivated by a need to consistently prove themselves worthy.[39]

See also

.

References

- ↑ http://www.oxforddictionaries.com/definition/english/optimism

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Bates, Timothy C. (25 February 2015). "The glass is half full and half empty: A population-representative twin study testing if optimism and pessimism are distinct systems". The Journal of Positive Psychology. doi:10.1080/17439760.2015.1015155.

- 1 2 Sharot, Tali (December 2011). "The optimism bias". Current Biology. 21 (23): R941–R945. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2011.10.030.

- 1 2 Vaughan, Susan C. (2000). Half Empty, Half Full: Understanding the Psychological Roots of Optimism. New York: Courtyard.

- ↑ Ron Gutman: The hidden power of smiling on YouTube

- ↑ Scheier, M. F.; Carver, C. S. (1987). "Dispositional optimism and physical well-being: the influence of generalized outcome expectancies on health". Journal of Personality. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1987.tb00434.x.

- ↑ House, J.; Landis, K.; Umberson, D (1988-07-29). "Social relationships and health". Science. 241 (4865): 540–545. doi:10.1126/science.3399889.

- ↑ Lorant, Vincent; Croux, Christophe; Weich, Scott; Deliège, Denise; Mackenbach, Johan; Ansseau, Marc (2007-04-01). "Depression and socio-economic risk factors: 7-year longitudinal population study". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 190 (4): 293–298. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.105.020040. ISSN 0007-1250. PMID 17401034.

- ↑ Carver, C. S.; Scheier, M. F. (1998). On the self-regulation of behavior. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Hooker, Karen; Monahan, Deborah; Shifren, Kim; Hutchinson, Cheryl. "Mental and physical health of spouse caregivers: The role of personality.". Psychology and Aging. 7 (3): 367–375. doi:10.1037/0882-7974.7.3.367.

- ↑ Herzberg, Philipp Yorck; Glaesmer, Heide; Hoyer, Jürgen. "Separating optimism and pessimism: A robust psychometric analysis of the Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R).". Psychological Assessment. 18 (4): 433–438. doi:10.1037/1040-3590.18.4.433.

- ↑ Robinson-Whelen, Susan; Kim, Cheongtag; MacCallum, Robert C.; Kiecolt-Glaser, Janice K. "Distinguishing optimism from pessimism in older adults: Is it more important to be optimistic or not to be pessimistic?". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 73 (6): 1345–1353. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.73.6.1345.

- 1 2 3 4 Gillham, Jane E.; Shatté, Andrew J.; Reivich, Karen J.; Seligman, Martin E. P. (2001). "Optimism, Pessimism, and Explanatory Style". In Chang, Edward C. Optimism and Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. pp. 53–75. ISBN 978-1-55798-691-7.

- ↑ Liu, Caimei; Bates, Timothy C. (2014-08-01). "The structure of attributional style: Cognitive styles and optimism–pessimism bias in the Attributional Style Questionnaire". Personality and Individual Differences. 66: 79–85. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2014.03.022.

- ↑ Peterson, C. (2000). "The Future of Optimism". American Psychologist. 55 (1): 44–55. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.44.

- ↑ Abramson, L.; Dykman, B.; Needles, D. (1991). "Attributional Style and Theory: Let No One Tear Them Asunder". Psychological Inquiry. 2 (1): 11–13. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0201_2.

- ↑ Zullow, H. (1991). "Explanations and Expectations: Understanding the 'Doing' Side of Optimism". Psychological Inquiry. 2 (1): 45–49. doi:10.1207/s15327965pli0201_13.

- 1 2 Schulman, P.; Keith, D.; Seligman, M. (1993). "Is Optimism Heritable? A Study of Twins". Behavior Research and Therapy. 31 (6): 569–574. doi:10.1016/0005-7967(93)90108-7.

- ↑ Scheier, Michael F.; Carver, Charles S. (1985). "Optimism, coping, and health: Assessment and implications of generalized outcome expectancies.". Health Psychology. 4 (3): 219–247. doi:10.1037/0278-6133.4.3.219. PMID 4029106.

- ↑ Scheier, Michael F.; Carver, Charles S.; Bridges, Michael W. "Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test.". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 67 (6): 1063–1078. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063.

- 1 2 Peterson, Christopher; Semmel, Amy; von Baeyer, Carl; Abramson, Lyn Y.; Metalsky, Gerald I.; Seligman, Martin E. P. (September 1982). "The Attributional Style Questionnaire". Cognitive Therapy and Research. 6 (3): 287–299. doi:10.1007/BF01173577.

- ↑ Peterson, Christopher; Park, Nansook; Kim, Eric S. (February 2012). "Can optimism decrease the risk of illness and disease among the elderly?". Aging Health. 8 (1): 5–8. doi:10.2217/ahe.11.81.

- ↑ Peterson, Christopher; Bossio, Lisa M. (2001). "Optimism and Physical Well-Being". In Chang, Edward C. Optimism and Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. pp. 127–145. ISBN 978-1-55798-691-7.

- ↑ Scheier, Michael F.; Matthews, Karen A.; Owens, Jane F.; et al. (1989). "Dispositional optimism and recovery from coronary artery bypass surgery: The beneficial effects on physical and psychological well-being". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 57 (6): 1024–1040. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1024. PMID 2614656.

- ↑ Kubzansky, Laura D.; Sparrow, David; Vokonas, Pantel; Kawachi, Ichiro (November 2001). "Is the Glass Half Empty or Half Full? A Prospective Study of Optimism and Coronary Heart Disease in the Normative Aging Study". Psychosomatic Medicine. 63 (6): 910–916. doi:10.1097/00006842-200111000-00009. PMID 11719629.

- ↑ Giltay, Erik J.; Geleijnse, Johanna M.; Zitman, Frans G.; Hoekstra, Tiny; Schouten, Evert G. (November 2004). "Dispositional Optimism and All-Cause and Cardiovascular Mortality ina Prospective Cohort of Elderly Dutch Men and Women". Archives of General Psychiatry. 61 (11): 1126. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.61.11.1126. PMID 15520360.

- ↑ Kim, Eric S.; Park, Nansook; Peterson, Christopher (October 2011). "Dispositional Optimism Protects Older Adults From Stroke: The Health And Retirement Study". Stroke. 42 (10): 2855–2859. doi:10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.613448. PMID 21778446.

- ↑ Giltay, Erik J.; Zitman, Frans G.; Kromhout, Daan (March 2006). "Dispositional optimism and the risk of depressive symptoms during 15 years of follow-up: The Zutphen Elderly Study". Journal of Affective Disorders. 91 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1016/j.jad.2005.12.027. PMID 16443281.

- ↑ Patton, George C.; Tollit, Michelle M.; Romaniuk, Helena; Spence, Susan H.; Sheffield, Jeannie; Sawyer, Michael G. (February 2011). "A Prospective Study of the Effects of Optimism on Adolescent Health Risks". Pediatrics. 127 (2): 308–16. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-0748. PMID 21220404.

- ↑ Affleck, Glenn; Tennen, Howard; Apter, Andrea (2001). "Optimism, Pessimism, and Daily Life With Chronic Illness". In Chang, E. Optimism & Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. pp. 147–168. ISBN 9781557986917.

- 1 2 Scheier, Michael F.; Carver, Charles S.; Bridges, Michael W. (2001). "Optimism, Pessimism, and Psychological Well-Being". In Chang, E. Optimism & Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. pp. 189–216. ISBN 1-55798-691-6.

- ↑ Bergland, Christopher. "Optimism Stabilizes Cortisol Levels and Lowers Stress."Psychology Today: Health, Help, Happiness + Find a Therapist. N.p., n.d. Web. . http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-athletes-way/201307/optimism-stabilizes-cortisol-levels-and-lowers-stress.

- 1 2 Scheier, Michael F.; Carver, Charles S. (April 1992). "Effects of optimism on psychological and physical well-being: Theoretical overview and empirical update". Cognitive Therapy and Research. 16 (2): 201–228. doi:10.1007/BF01173489.

- ↑ Alarcon, Gene M.; Bowling, Nathan A.; Khazon, Steven (May 2013). "Great expectations: A meta-analytic examination of optimism and hope". Personality and Individual Differences. 54 (7): 821–827. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2012.12.004.

- ↑ Giltay, Erik J.; Geleijnse, Johanna M.; Zitman, Frans G.; Buijsse, Brian; Kromhout, Daan (November 2007). "Lifestyle and dietary correlates of dispositional optimism in men: The Zutphen Elderly Study". Journal of Psychosomatic Research. 63 (5): 483–490. doi:10.1016/j.jpsychores.2007.07.014. PMID 17980220.

- 1 2 "Positive thinking: Stop negative self-talk to reduce stress". Mayo Clinic. March 4, 2014. Retrieved September 18, 2014.

- ↑ Rescher, Nicholas (June 2000). "Optimalism and axiological metaphysics". The Review of Metaphysics. 53 (4): 807–35. ISSN 0034-6632.

- ↑ Steinhart, Eric. "Platonic Atheism" (PDF). Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- 1 2 3 Tal Ben-Shahar (11 March 2009). The Pursuit of Perfect: How to Stop Chasing Perfection and Start Living a Richer, Happier Life. McGraw-Hill Professional. pp. 7–. ISBN 978-0-07-160882-4. Retrieved 26 July 2011.

- ↑ Parker, W. D.; Adkins, K. K. (1994), "Perfectionism and the gifted", Roeper Review, 17 (3): 173–176, doi:10.1080/02783199509553653

- 1 2 Horne, Amanda. "Positive Psychology News Daily". Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- ↑ Staff (May 1995), "Perfectionism: Impossible Dream", Psychology Today

Mayo Clinic Staff. "Positive thinking: Stop negative self-talk to reduce stress" Mayoclinic.org. Mayo Clinic, 4 March 2014. Web. 31 March 2014.

Further reading

- Chang, E. (2001). Optimism & Pessimism: Implications for Theory, Research, and Practice, Washington, DC: American Psychological Association. ISBN 1-55798-691-6.

- Huesemann, Michael H., and Joyce A. Huesemann (2011). Technofix: Why Technology Won’t Save Us or the Environment, Chapter 7, “Technological Optimism and Belief in Progress”, New Society Publishers, Gabriola Island, British Columbia, Canada, ISBN 0865717044, 464 pp.

- Seligman, M.E.P., (2006). Learned Optimism: How to Change Your Mind and Your Life, Vintage, ISBN 1400078393.

- Sharot, Tali (2012). The Optimism Bias: A Tour of the Irrationally Positive Brain, Vintage, ISBN 9780307473516.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Optimism |

| Wikiversity has learning materials about Positive thinking |

| Wikiversity has learning materials about Optimism |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Optimism. |

- Being Optimistic Optimism As Character Strength

- Ehrenreich, Barbara (2010). Bright-Sided: How Positive Thinking Is Undermining America. Picador. p. 256. ISBN 9780312658854. Retrieved 2013-07-29.

- "Tali Sharot: The optimism bias", Tali Sharot's talk at the TED.com