Poniatowa concentration camp

| Poniatowa concentration camp | |

|---|---|

| Concentration camp | |

|

Forced labor camp at Poniatowa, the workshop of WC Toebbens

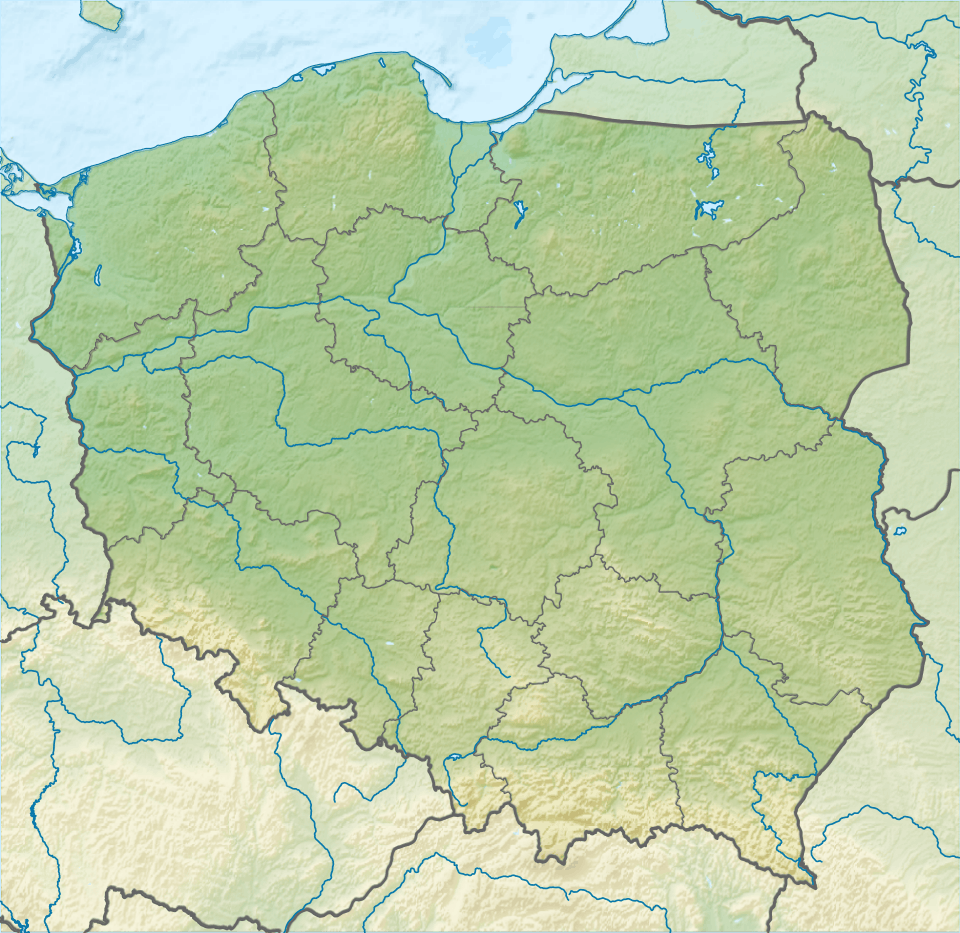

Poniatowa location during the Holocaust in Poland. Demarcation line, red. Poland's borders before the invasion of 1939.  Poniatowa concentration camp Former location in present-day Poland | |

| Coordinates | 51°06′19″N 22°02′27″E / 51.1054°N 22.0407°ECoordinates: 51°06′19″N 22°02′27″E / 51.1054°N 22.0407°E |

| Other names | Stalag 359 Poniatowa |

| Location | Poniatowa, Poland |

| Operational | 1941-1943 |

| Notable inmates | Israel Shahak |

Poniatowa concentration camp in the town of Poniatowa in occupied Poland, 36 kilometres (22 mi) west of Lublin, was established by the SS in the latter half of 1941 initially, to hold Soviet prisoners of war following Operation Barbarossa. By mid-1942, about 20,000 Soviet POWs had perished there from hunger, disease and executions. The camp was known at that time as the Stalag 359 Poniatowa. Afterwards, the Stammlager was redesigned an expanded as a concentration camp to provide slave labour supporting the German war effort, with workshops run by the SS Ostindustrie (Osti) on the grounds of the prewar Polish telecommunications equipment factory founded in the late 1930s.[1] Poniatowa became part of the Majdanek concentration camp system of subcamps in the early autumn of 1943.[2] The wholesale massacre of its mostly Jewish workforce took place during the Aktion Erntefest, thus concluding the Operation Reinhard in General Government.[3][4]

Camp operation

Two years into the invasion of Poland by Nazi Germany, in October 1942 Hauptsturmführer Amon Göth – soon to become the commandant of Kraków-Płaszów – visited Poniatowa with a blueprint for redevelopment. The construction of a brand new forced labor camp was assigned to Erwin Lambert. The camp was meant to supply workers for the Walter Többens army-uniform factory relocated from the vanishing Warsaw Ghetto, where at least 254,000 Jews were sent to Treblinka extermination camp in two months of summer 1942. Obersturmführer Gottlieb Hering was appointed the camp commandant. He was promoted to the rank of SS-Hauptsturmführer by Himmler in March 1943.[4][5]

The first transport of Jews arrived at Poniatowa in October 1942 from Opole where the ghetto liquidation to Sobibor extermination camp was under way. The new barracks were built. By January 1943 there were 1,500 Jews in the camp. In April 1943, during the Nazi eradication of the Warsaw Ghetto, about 15,000 more Polish Jews were delivered. For the next six months, they all produced fresh garments for the Wehrmacht. Due to the nature of the work performed, the prisoners were not maltreated like in most other camps. They were allowed to keep children through daycare, wear their own clothes, and retain their personal effects, because the new uniforms made by them, were great morale boosters at the Front. The Jewish tailors and seamstresses of Warsaw worked practically free of charge for the German war profiteer Walter Caspar Többens (Toebbens) who was making a fortune. He was later described as the anti-Schindler.[6] The Jews of Poland were augmented by around 3,000 Slovakian and Austrian Jews (the camp elite) housed separately from the rest.[7]

Aktion Reinhard

After the closure of the nearby Belzec death factory in June 1943,[8] head of the Operation Reinhard, Obergruppenführer Odilo Globocnik inspected the Poniatowa facility in August 1943. Gottlieb Hering, the camp commandant,[4] was reprimanded for a total lack of prison discipline. Drastic changes were introduced immediately with daily executions of at least several people. The new crematorium was constructed.[9] From September 1943, the Poniatowa forced labor camp became part of the KL Majdanek concentration camp system of subcamps under Aktion Reinhard, the most deadly phase of the Holocaust.[10]

.jpg)

At the beginning of secretive Operation Harvest Festival (Aktion Erntefest) the inmates were ordered to dig anti-aircraft trenches at Poniatowa, Trawniki, as well as at the Majdanek concentration camps, unaware of their true purpose.[4] On 3 November 1943, by the orders of Christian Wirth, the German SS and police began shooting Jews from the camps at these locations. They were massacred simultaneously across the entire Lublin Reservation with subcamps in Budzyn, Kraśnik, Puławy, Lipowa and other places.[11] At Poniatowa, the inmates were compelled to undress and enter the self-prepared trenches naked, where they were shot one-by-one over the bodies of others.[12]

The uprising

On the first day of killings, in one of the barracks at Poniatowa Jews staged a revolt. To stamp it out the SS surrounded the building by a tight cordon, and set it on fire. The smoke triggered the arrival at the gate of a fire brigade from the village because gendarmes were not informed. According to witness, more than one structure was burning at the camp. The firemen were ordered by the screaming SS to leave immediately, but inadvertently noticed that a Jew running from the flames was bludgeoned with rifle butts, and thrown back into the burning building. The area was covered with bodies of women. The next morning (4 November 1943), mass killings at Poniatowa went on as planned and continued for the rest of the day.[13] In total, on 3–4 November 1943 some 43,000 male and female prisoners were shot over a long line of fake anti-aircraft trenches. The camps were closed.[14] Commandant Gottlieb Hering then joined fellow SS-men from the Operation Reinhard staff at Risiera di San Sabba in Trieste, Italy.[15][5][9][16][17]

Commemoration

The first two monuments in memory of the victims of Nazism at Poniatowa were erected in communist Poland at the city centre in 1958 and at the PZT factory in 1959. A different monument, commemorating only the Jewish victims of the Holocaust was unveiled in Poniatowa on 4 November 2008, for the 65 anniversary of their deaths. The inscription in both Polish and English mentions the 14,000 victims of the Aktion Erntefest in Poniatowa from across Poland, Germany, Austria and Czechoslovakia (without the remaining locations). The monument was unveiled in the presence of the ambassador of Israel to Poland David Peleg, the ambassador of Austria Alfred Langle; Andreas Meitner, minister from the German embassy; Jan Tomaszek, minister from the Czech embassy; Henryka Strojnowska, voivode of Lublin; the town mayor Lilla Stefanek, and many other officials, including Warsaw rabbi and priests.[18]

Notable survivors

- Estera Rubinstein, survived beneath the dead bodies of others. Testimony No. 301/1013 at the archives of Żydowski Instytut Historyczny (ŻOB).[19]

- Ludwika Fiszer, escaped from the mass grave. Testimony (45 pages) in the book Destruction and Rising published by the General Federation of Jewish Labour in Eretz Israel, Tel Aviv 1946 (digitized by Yad Vashem).[20]

- Israel Shahak, Israeli professor of chemistry at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Notes

- ↑ Michał Kaźmierczak, Poniatowa unofficial site with links to History and Gallery of photographs. Retrieved April 19, 2013. Location of Poniatowa factory: 51°10′23″N 22°04′10″E / 51.173172°N 22.069564°E

- ↑ "Forced labor-camps in District Lublin: Budzyn, Trawniki, Poniatowa, Krasnik, Pulawy, Airstrip and Lipowa camps". Holocaust Encyclopedia: Lublin/Majdanek Concentration Camp. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ↑ Jennifer Rosenberg. "Aktion Erntefest". 20th Century History. About.com Education. Retrieved 2013-04-16.

- 1 2 3 4 "Aktion Erntefest". Interrogation of Sporrenberg – National Archives Kew WO 208/4673. Holocaust Research Project.org. 2007. Retrieved 2013-04-17.

- 1 2 Szmuel Krakowski, Poniatowa. Source: Robert Rozett & Shmuel Spector: "Encyclopedia of the Holocaust", Yad Vashem & Facts On File, Inc., Jerusalem, 2002. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ↑ Günther Schwarberg (2010). "Walter Caspar Többens: the anti-Schindler". Le camp de concentration de Poniatowa (in French). Encyclopédie B&S Editions. Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- ↑ Alexander Donat, The Holocaust kingdom: a memoir (London, 1965), pp.216-217. Retrieved April 19, 2013

- ↑ "Belzec extermination camp". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- 1 2 Kaj Metz, Concentration Camp Poniatowa. Traces of War.com. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ↑ "Trawniki". Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ↑ ARC (2004). "Erntefest". Occupation of the East. ARC. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ↑ Jakub Chmielewski (2013). "Obóz pracy w Poniatowej". Obozy pracy w dystrykcie lubelskim (Labor camps in the Lublin District). Leksykon Lublin. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

- ↑ Jakub Chmielewski (2013). "Obóz pracy w Poniatowej". Likwidacja obozu pracy w Poniatowej i bunt więźniów (Prisoner Uprising). Leksykon Lublin. Retrieved 2013-04-26.

Protokół przesłuchania Franciszka Furtasa na temat egzekucji z 4 XI 1943 r. w Poniatowej, [in:] 3-4 listopada 1943. Erntefest zapomniany epizod Zagłady, ed. W. Lenarczyk, D. Libionka, Lublin 2009, s. 455 – 456.

- ↑ Re: Morgen affidavit at International Military Tribunal (Red Volume series), Supplement Volume B, pp. 1309-11 (Part II. 5. "Ernst Kaltenbrunner"). Nuremberg War Crimes Trials. PDF direct download, 25.0 MB. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ↑ Poniatowa Labour Camp. Factory buildings. Administration. Prisoner Barracks. Holocaust Education & Archive Research Team.

- ↑ ARC (16 July 2006), "The forced labour camp in Poniatowa." Death Camps.org (WebCite). Retrieved April 19, 2013.

- ↑ Operation Reinhard (Einsatz Reinhard). Holocaust Encyclopedia. United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington, D.C.

- ↑ Rafał Pastwa (2010). "65 rocznica likwidacji niemieckiego obozu pracy". Poniatowa - Miejsce Martyrologii Narodow. Towarzystwo Przyjaciol Poniatowej. Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- ↑ "Nazistowski obóz pracy przymusowej w Poniatowej". Miejsca martyrologii - Zabytki - Poniatowa. Virtual Shtetl. 2013. Retrieved 2013-04-19.

- ↑ "The Liquidation of the Camp in Poniatowa". Testimony of Ludwika Fiszer. Poniatowa Memorial Web Page. August 22, 2003. pp. 45 pages. Retrieved April 19, 2013.

References

- Kudryashov, Sergei (2004). "Ordinary Collaborators: The Case of the Travniki Guards". In Erickson, Ljubica; Erickson, Mark. Russia War, Peace And Diplomacy: Essays in Honour of John Erickson. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. pp. 226–239. ISBN 978-0-297-84913-1 – via Google Books, no preview.

- Steinhart, Eric C. (2009). "The Chameleon of Trawniki: Jack Reimer, Soviet Volksdeutsche, and the Holocaust". Holocaust and Genocide Studies. 23 (2): 239–262. doi:10.1093/hgs/dcp032. ISSN 8756-6583.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum - Trawniki.

- In depth overview of the Trawniki Camp, Trawniki Staff, Photos. - All about Trawniki. Holocaust Research Project.net

- Robin O'Neil, Belzec: Stepping Stone to Genocide, Sources of Manpower. OCLC 779194210