Balhae

| Balhae | ||||||||||||||

| 발해 (渤海) | ||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

The territory of Balhae, in 830s during the reign of King Seon of Balhae. | ||||||||||||||

| Capital | Dongmo mountain (698–742) Junggyeong (742–756) Sanggyeong (756–785) Donggyeong (785–793) Sanggyeong (793–926) | |||||||||||||

| Languages | Goguryeo language (Part of Old Korean) | |||||||||||||

| Religion | Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, Shamanism | |||||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | |||||||||||||

| King | ||||||||||||||

| • | 698–719 | Go | ||||||||||||

| • | 719–737 | Mu | ||||||||||||

| • | 737–793 | Mun | ||||||||||||

| • | 818–830 | Seon | ||||||||||||

| Historical era | Ancient | |||||||||||||

| • | Establishment | 698 | ||||||||||||

| • | Fall of Sanggyeong | January 14, 926 | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||

| Today part of | | |||||||||||||

| Balhae | |||||||

| Korean name | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hangul | 진, then 발해 | ||||||

| Hanja | 震, then 渤海 | ||||||

| |||||||

Part of a series on the |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| History of Korea | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Prehistory | ||||||||

| Ancient | ||||||||

| Proto–Three Kingdoms | ||||||||

| Three Kingdoms | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| North–South States | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Later Three Kingdoms | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Unitary dynastic period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Colonial period | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| Division of Korea | ||||||||

|

||||||||

| By topic | ||||||||

| Timeline | ||||||||

|

| ||||||||

Part of a series on the |

|---|

| History of Manchuria |

|

Medieval period |

| Monarchs of Korea Balhae |

|---|

|

Balhae (Hangul: 발해; Hanja: 渤海; Korean pronunciation: [paɾhɛ]) was a medieval kingdom of the Goguryeo and Mohe peoples in the northern Korean Peninsula and southeastern Manchuria. It existed during Korea's North–South States Period along with Later Silla.

Balhae was established under the name Jin by King Go in 698 after his defeat of the Tang Empire at Tianmenling. It eventually occupied areas within present-day northern Korea, areas of China's Northeast, and Russia's Maritime Province. It was defeated by the Khitans in 926. Most of its northern territories were absorbed into their Liao dynasty, while the southern parts were absorbed into Goryeo.

Name

Balhae was founded in AD 698 under the name "Jin" or "Chin". This is the modern Revised Romanization of Korean 진, the same as the earlier Jin Kingdom. However, that kingdom wrote its own name as 辰 using Korean Hanja characters (hanja), with the reconstructed Old Chinese pronunciation /*[d]ər/ and the Middle Chinese pronunciation dzyin;[1] King Go's state wrote its name as 震, with the Middle Chinese pronunciation tsyin.[1] The former state's character referred to the 5th earthly branch of the Chinese and Korean zodiacs, a division of the orbit of Jupiter identified with the dragon. This was associated with a bearing of 120° (between ESE and SE) but also with the two-hour period between 7 and 9 am, leading it to be associated with dawn and the direction east. The latter state's name may have simply been a variant transcription of this or may have intended the second character's meaning of "thunderclap", "shock", "tremor", &c.

In 712, the state was renamed "Balhae", the Korean form of the Sea of Bohai.

History

Founding

The earliest extant recorded mention of Balhae comes from the Old Book of Tang, which was compiled between 941 and 945. Southern Manchuria and northern Korea were previously the territory of Goguryeo, one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea. Goguryeo fell to the allied forces of Silla and the Tang dynasty in 668. The Tang annexed much of western Manchuria, while Silla unified the Korean peninsula south of the Taedong River and became Later Silla.

In the confusion of uprising by the Khitan people against the Tang, Dae Jung-sang, a former Goguryeo official[2][3] who was a leader of a remnant of Goguryeo, allied with Geolsa Biu, a leader of the Mohe people, and rose against the Tang in 698 as Go. After Dae Jungsang’s death, his son, Dae Jo-yeong, a former Goguryeo general[4][5] succeeded his father. Geolsa Biu died in battle against the Tang army led by the general Li Kaigu. Dae jo Yeong managed to escape outside of the Tang controlled territory with the remaining Goguryeo and Mohe soldiers. He successfully defeated a pursuing army sent by Wu Zetian at the Battle of Tianmenling. which enabled him to establish the state of Balhae in the former region of Yilou as King Go.[6]

Expansion and foreign relations

The second King Mu (r. 719-737), who felt encircled by Tang, Silla and Black Water Mohe along the Amur River, attacked Tang with his navy in 732 and killed a Tang prefect based on the Shandong Peninsula.[7] In the same time, the king led troops taking land routes to Madushan (馬都山) in the vincity of the Shanhai Pass (about 300 kilometres east of current Beijing) and occupied towns nearby.[8] He also sent a mission to Japan in 728 to threaten Silla from the southeast. Balhae kept diplomatic and commercial contacts with Japan until the end of the kingdom. Balhae dispatched envoys to Japan 34 times, while Japan sent envoys to Balhae 13 times.[9] Later, a compromise was forged between Tang and Balhae, which led Tang diplomatically recognize Mun of Balhae, who succeeded to his father's throne, as King of Balhae.

The third Emperor Mun (r. 737-793) expanded its territory into the Amur valley in the north and the Liaodong Peninsula in the west. During his reign, a trade route with Silla, called "Sillado" (신라도, 新羅道), was established. Emperor Mun moved the capital of Balhae several times. He also established Sanggyeong, the permanent capital near Lake Jingpo in the south of today's Heilongjiang province around 755; stabilizing and strengthening central rule over various ethnic tribes in his realm, which was expanded temporarily. He also authorized the creation of the Jujagam (胄子監), the national academy, based on the national academy of Tang. Although China recognized him as a king, Balhae itself referred to him as the son of heaven and an emperor.[10]

The tenth King Seon reign (r. 818-830), Balhae controlled northern Korea, Northeastern Manchuria and now Primorsky Krai of Russia. King Seon led campaigns that resulted in the absorbing of many northern Mohe tribes and southwest Little Goguryeo kingdom, which was located in the Liaodong Peninsula, was absorbed into Balhae. Its strength was such that Silla was forced to build a northern wall in 721 as well as maintain active defences along the common border.

Fall and legacy

Following the reign of King Seon (830), there is no surviving written records of Balhae. Some scholars believe that the eruption of Mt. Baekdu may have caused a national level catastrophe leading to its final fall to the Khitan kingdom of Liao Dynasty, while certain other historians believe that ethnic conflicts between the ruling Koreans and underclass Mohe weakened the state.[11] The Khitans were centered in Liaoning and Inner Mongolia, which overlaps Balhae's purported territories in the west. A Khitan invasion took the capital of Balhae after a 25-day siege in 926. After destroying Balhae in 926, the Khitans established a puppet Dongdan Kingdom, which was soon annexed by Liao in 936. Most Balhae aristocrats were moved to Liaoyang, but Balhae's eastern territory remained politically independent. Goryeosa records the arrival of 10,000 Balhae people led by a general escaping from the Khitans in 925, one year before the final collapse of the kingdom. The rest of Balhae people were assimilated into the Khitan polity as well as the Jurchens who would revolt against the Khitans later in the century. Some descendants of the 10,000 Balhae emigre in Goryeo changed their family name to Tae (태, 太) while Crown Prince Dae Gwang-hyeon was given the family name Wang (왕, 王), the royal family name of the Goryeo dynasty. Balhae was the last state in Korean history to hold any significant territory in Manchuria, although later Korean dynasties would continue to regard themselves as successors of Goguryeo and Balhae.

The Khitans themselves eventually succumbed to the Jurchen people, who founded the Jin dynasty. Jurchen proclamations emphasized the common descent of the Balhae and Jurchen people from the seven Wuji (勿吉) tribes, and proclaimed "Jurchen and Balhae are from the same family". The fourth, fifth and seventh emperors of Jin were mothered by Balhae consorts. The 13th century census of Northern China by the Mongols distinguished Balhae from other ethnic groups such as Goryeo, Khitan and Jurchen.

Aftermath

After the fall of Balhae and its last king in 926, it was renamed Dongdan by its new Khitan rulers,[12] who had control over most of Balhae's old territories. However, starting from 927, many rebellions were triggered throughout the domains. These rebellions were eventually turned into several Balhae revivals. Out of these, only three succeeded and established kingdoms: Later Balhae, Jeong-an kingdom, Heung-yo kingdom and Daewon kingdom. These three kingdoms were able to temporarily chase the Khitan and their Dongdan Kingdom out into the Liaodong peninsula, but they were all eventually devastated by the Liao Empire.

In 925, Dae Gwang-hyeon, the last Crown Prince of Balhae, revolted against the Khitans. After being defeated, he fled to Goryeo, where he was granted protection and the imperial surname by Wang Geon, thus unifying the two successor nations of Goguryeo.[13] This resulted in the Liao breaking off diplomatic relations with Goryeo, but there was no threat of invasion. He brought about 10,000 men with him.[14]

Government and culture

Balhae was made up of former Goguryeo remnant peoples and of several Tungusic peoples present in Manchuria, of which the native Mohe made up partly. The Mohe was forced into inferior working class status into serving the Goguryeo ruling class.[11] As such, they made the bulk of the labor class, as well as a majority of the population. Nevertheless, there were instances of Mohe moving upward into the Balhae elite, however few, such as the followers of Geolsa Biu, who supported the estalblishment of Balhae. They were limited to the title of "Suryong", or "chief", which is derived from Old Goguryoan language[15] and played a part in the ruling elite. Although rare, some members of Balhae embassies held Mohe surnames.

Because all written records from Balhae itself have been lost, all information concerning the kingdom must be gained from archaeological excavation and contemporary Chinese accounts. After its founding, Balhae actively imported aspects of the culture and political system of Tang dynasty China. Archaeologists studying the layout of Balhae's cities have conclude that Balhae cities shared features common with cities in Goguryeo, indicating that Balhae retained cultural similarities with Goguryeo after its founding.[16] According to Chinese accounts, Balhae had five capitals, fifteen provinces, and sixty-three counties.[17]

It is noted that Balhae was a culturally advanced society, as an official from China described it as the "flourishing land of the East." The government operated three chancelleries and six ministries. It is obvious that Balhae's structure was modelled after the Chinese system, however it did not entirely conform to that of the Tang. The "taenaesang" or the "great minister of the court" was superior to the other two chancelleries (the left and the right) and its system of five capitals originates from Goguryeo's administrative structure. Balhae, like Silla, sent many students to Tang to study, and many went on to take and pass the Chinese civil service examinations.[18] As consequence, the Balhae capital of Sanggyong was organized in the way of Tang's capital of Chang'an. Residential sectors were laid out on either side of the palace surrounded by a rectangular wall.

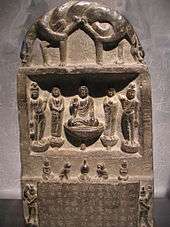

The principal roots of Balhae culture was that of Goguryeo origins. An Ondol installation was uncovered in the inner citidel of the Balhae palace and many others adjacent to it. Furthermore, Buddhist statuaries and motifs were found in Balhae temples that reflect that of distinctive Goguryeo art. An important source of cultural information on Balhae was discovered at the end of the 20th century at the Ancient Tombs at Longtou Mountain, especially the Mausoleum of Princess Jeonghyo.

Characterization and political interpretation

Controversy rests over the ethnic makeup of the people of Balhae. That Balhae was founded by a former general from Goguryeo is undisputed, but there is some dispute over his ethnicity, due to ambiguous wording in historical sources. No written records from Balhae itself survive.

Modern Korean scholars have generally regarded Balhae as an extension of the Korean Goguryeo kingdom (37 B.C. - 668 A.D.) ever since the publication of Jewang ungi.[19] The 18th century, during the Joseon Dynasty, was a period in which Korean scholars began a renewed interest in Balhae. The Qing and Joseon dynasties had negotiated and demarcated the Sino-Korean border along the Yalu and Tumen rivers in 1712, and Jang Ji-yeon (1762–1836), journalist, writer of nationalist tracts, and organizer of nationalist societies, published numerous articles arguing that had the Joseon officials considered Balhae part of their territory, they would not be as eager to "give up" lands north of the rivers. Yu Deuk-gong in his 18th-century work Balhaego (An investigation of Balhae) argued that Balhae should be included as part of Korean history, and that doing so would justify territorial claims on Manchuria. Korean historian Sin Chae-ho, writing about Jiandao in the early 20th century, bemoaned that for centuries, Korean people in their “hearts and eyes considered only the land south of the Yalu River as their home” and that “half of our ancestor Dangun's ancient lands have been lost for over nine hundred years.” Sin also criticized Kim Busik, author of the Samguk Sagi, for excluding Balhae from his historical work and claiming that Silla had achieved unification of Korea.[20] Inspired by ideas of Social Darwinism, Sin wrote:

- "How intimate is the connection between Korea and Manchuria? When the Korean race obtains Manchuria, the Korean race is strong and prosperous. When another race obtains Manchuria, the Korean race is inferior and recedes. Moreover, when in the possession of another race, if that race is the northern race, then Korea enters that northern race's sphere of power. If an eastern race obtains Manchuria, then Korea enters that race's sphere of power. Alas! This is an iron rule that has not changed for four thousand years."[21]

Neither Silla nor the later Goryeo wrote an official history for Balhae, and some modern scholars argue that had they done so, Koreans might have had a stronger claim to Balhae's history and territory.[22]

In modern North and South Korea, Balhae is regarded as a Korean state and is positioned in the "North South States Period" (with Silla) today, although such a view has had proponents in the past. They emphasize its connection with Goguryeo and minimize that with the Mohe. While South Korean historians think the ethnicity ruling class was of Goguryeo and the commoners were mixed, including Mohe, North Korean historians think Balhae ethnography was mostly Goguryeo. Koreans believe the founder Dae Joyeong was of Goguryeo stock. The Old Book of Tang says that "Dae Joyeong of the Balhae-Mohe, was originally from a division of Goguryeo" (渤海靺鞨大祚榮者,本高麗別種也.),[23]

In the West, Balhae is generally characterized as a successor to Goguryeo that traded with China and Japan, and its name is romanized from Korean.[24][25][26] An alternate Romanization from Korean, as "Parhae", and Romanization from Chinese, as "Bohai", are also common in English.[16][27][28][29] It is seen as composed of peoples of northern Manchuria and northern Korea, with its founder and the ruling class consisting largely of the former aristocrats of Goguryeo. Korean scholars believe Balhae founder Dae Joyeong was of Goguryeo ethnicity, while others believe he was an ethnic Mohe from Goguryeo.[30][31][32][33]

Like many ancient Korean kingdoms and other states, Balhae often paid tribute to China, and an heir who lacks this sanction was called by China 知國務 ("State Affairs Leader"), not king; also, China considered every king simultaneously the Prefect of Holhan Prefecture (忽汗州都督府都督).[34] However, Balhae rulers called themselves emperors and declared their own era names.

“建州毛怜则渤海大氏遗孽,乐住种,善缉纺,饮食服用,皆如华人,自长白山迤南,可拊而治也。" "The (people of) Chien-chou and Mao-lin [YLSL always reads Mao-lien] are the descendants of the family Ta of Po-hai. They love to be sedentary and sow, and they are skilled in spinning and weaving. As for food, clothing and utensils, they are the same as (those used by) the Chinese. (Those living) south of the Ch'ang-pai mountain are apt to be soothed and governed."

据魏焕《皇明九边考》卷二《辽东镇边夷考》[35] Translation from Sino-J̌ürčed relations during the Yung-Lo period, 1403-1424 by Henry Serruys[36]

According to news articles citing a recent US report, China considers Balhae to be a province of the Tang Dynasty.[37][38] This view is linked to the Northeast Project of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences conducted by the Chinese Academy of Social Science. China also considers Balhae as part of the history of its ethnic Manchus.[39] Chinese historians insist Balhae to be composed of the Balhae ethnic group, which was mostly based on the Mohe. The New Book of Tang states that the Balhae "was originally the Sumo Mohe, began to ally themselves with Goguryeo, and took the surname Dae." (Dae is 大 in Chinese, Wade Giles : Ta ; Pinyin : Da)(渤海,本粟末靺鞨附高丽者,姓大氏.),[40] The Samguk Sagi and the Tang dynasty Tongdian stated that Balhae was originally Limo Mohe.[41] The Ruijū Kokushi says that Mohe tribes founded Balhae and made up the majority of Balhae.[42]

Historically, the Jurchens (later renamed the Manchus), considered themselves as sharing ancestry with the Mohe. According to the Book of Jin (金史), the history of the Jurchen Jin Dynasty (1115–1234), Jin founder Wanyan Aguda once sent an edict to Balhae claiming that "the Jurchens and Balhae were originally of the same family" (女直渤海本同一家).[43] An earlier, opposing view comes from Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai, who said in 1963 that Korean people have lived in the northeastern region of China since ancient times and excavated relics prove that Balhae is a branch of ancient Korea. The former Chinese premier's remarks have been made public through a document entitled “Premier Zhou Enlai's Dialogue on Sino-Korean Relations.“[44]

The People's Republic of China is accused of limiting Korean archaeologists access to historical sites located within Liaoning and Jilin. Starting from 1994, increasing numbers of South Korean tourists began to visit archaeological sites in China and often engaged in nationalistic displays. This was aggravated by a series of tomb robberies and vandalism at several of these archaeological sites between 1995 and 2000.[45]

South Korean archeologist Song Ki-ho, a noted professor at Seoul National University who has published several papers criticizing the Chinese government's interpretation of Balhae's history, made several visits to China in the 1990s, 2000, 2003, and 2004, examining several historical sites and museums. However, he found himself restricted by limitations on note-taking and photography and was even ejected from several sites by museum employees.[46][47]

North Korea has restricted independent archaeologists from its historical sites, many of which may be Balhae-related, since at least the early 1960s. Foreign scholars have criticized political bias in North Korean historiography, and have accused North Korean scholars of reconstructing or even fabricating historical sites.[48]

Scholars from South and North Korea, Russia and Japan assert that Balhae was independent in its relations with the Tang Dynasty. Most Russian archaeologists and scholars describe Balhae as a kingdom of displaced Goguryeo people.[48][49] They do admit that Balhae had a strong Chinese and Central Asian influence.[50]

In relations with Japan, Balhae referred to itself as Goguryeo, and Japan welcomed this as a kind of restoration of its former friendly relationship with Goguryeo.[51][52]

Finnish linguist Juha Janhunen believes that it was likely that a "Tungusic-speaking elite" ruled Goguryeo and Balhae, describing them as "protohistorical Manchurian states" and that part of their population was Tungusic, and that the area of southern Manchuria was the origin of Tungusic peoples and inhabited continuously by them since ancient times, and Janhunen rejected opposing theories of Goguryeo and Balhae's ethnic composition.[53]

Media

Balhae features in the Korean film Shadowless Sword, about the last prince of Balhae, and Korean TV drama Dae Jo Yeong, which aired from September 16, 2006 to December 23, 2007, about its founder.

See also

- Ancient Tombs at Longtou Mountain

- History of Korea

- List of Korea-related topics

- List of Provinces of Balhae

- List of rulers of Balhae

- Balhae language

References

- 1 2 Baxter-Sagart.

- ↑ Compendium of the Five Dynasties 五代會要(Wudai Huiyao): ... 高麗別種大舍利乞乞仲象

- ↑ Compendium of the Five Dynasties 五代會要(Wudai Huiyao): ... 大姓舍利官乞乞仲象名也

- ↑ Old records of Silla 新羅古記(Silla gogi): ... 高麗舊將祚榮

- ↑ Rhymed Chronicles of Sovereigns 帝王韻紀(Jewang ungi): ... 前麗舊將大祚榮

- ↑ Compendium of the Five Dynasties 五代會要(Wudai Huiyao): ... 保據挹婁故地

- ↑ Zizhi Tongjian, vol. 213. This episode was first mentioned in the Old Book of Tang, chapter 199B, p. 5361 of the standard Zhonghua shuju edition.

- ↑ New History of Tang Dynasty Wuchengci zhuan, p.4597; Comprehensive Mirror to Add in Government, Vol.210, Xuanzhong Kaiyuan 21th Year, January, “Kaoyi”,p.6800

- ↑ 9 Balhae and Japan Northeast Asian History Foundation

- ↑ Ŕ̿ϹŮ. "야청도의성(夜聽도衣聲)". Seelotus.com. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- 1 2 Lee Ki-baik. "The Society and Culture of Parhae." The New History of Korea, page 88-89. Harvard University Press, 1984.

- ↑ [Mote p. 49]

- ↑ Lee, Ki-Baik (1984). A New History of Korea. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 103. ISBN 067461576X. "When Parhae perished at the hands of the Khitan around this same time, much of its ruling class, who were of Koguryŏ descent, fled to Koryŏ. Wang Kŏn warmly welcomed them and generously gave them land. Along with bestowing the name Wang Kye ("Successor of the Royal Wang") on the Parhae crown prince, Tae Kwang-hyŏn, Wang Kŏn entered his name in the royal household register, thus clearly conveying the idea that they belonged to the same lineage, and also had rituals performed in honor of his progenitor. Thus Koryŏ achieved a true national unification that embraced not only the Later Three Kingdoms but even survivors of Koguryŏ lineage from the Parhae kingdom."

- ↑ [Mote p. 62]

- ↑ North Korea: A Country Study by Robert l. Worden

- 1 2 Ogata, Noboru. "A Study of the City Planning System of the Ancient Bohai State Using Satellite Photos (Summary)". Jinbun Chiri. Vol.52, No.2. 2000. pp.129 - 148. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ↑ Ogata, Noboru. "Shangjing Longquanfu, the Capital of the Bohai (Parhae) State". Kyoto University. January 12, 2007. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ↑ "North Korea - Silla". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- ↑ Joo Yong-lip (1991) Wang Cheng-li, Bohai Jianshi,; Li Dian-fu & Sun Yu-liang, Bohai guo; Yang Bao-long, Bohai-shi rumen

- ↑ Andre Schmid (2000). "Looking North toward Manchuria". The South Atlantic Quarterly. 99 (1): 219–240. doi:10.1215/00382876-99-1-219.

- ↑ Andre Schmid (1997). "Rediscovering Manchuria: Sin Ch'aeho and the Politics of Territorial History in Korea". The Journal of Asian Studies ( – Scholar search). 56 (1): 30. doi:10.2307/2646342. JSTOR 00219118. Sin was criticizing previous generations of Korean historians, who had traced Korean history back to the ancient peoples of the Korean peninsula. Sin believed that by doing so, and regarding "minor peoples" as their ancestors, they were diluting and weakening the Korean people and their history. He believed that the Korean race was in fact mainly descended from northern peoples, such as Buyeo, Goguryeo, and Balhae, and (re)claiming such a heritage would make them strong.

- ↑ Sources of Korean Tradition: from the sixteenth to the twentieth centuries - Google Books. Books.google.com.

- ↑ Old Book of Tang, Original: 渤海靺鞨大祚榮者,本高麗別種也. Link

- ↑ "24 X 7". Infoplease.com. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ↑ "North Korea - Silla". Countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ↑ http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/ht/06/eak/ht06eak.htm

- ↑ Kim, Alexander. "The Historiography of Bohai in Russia". The Historian. Vol.73, Issue 2. pp 284–299. June 8, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2011

- ↑ Pike, John. "Balhae / Bohai - 698AD-926AD". Globalsecurity.org. November 7, 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Parhae". Encyclopædia Britannica Online Academic Edition. 2011. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Parhae (ancient state, China) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ↑ Keith Pratt (1999). Korea: A Historical and Cultural Dictionary. Curzon Press. p. 340. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ↑ The Koreans: Contemporary Politics And Society, Third Edition - Donald S Macdonald, Donald N Clark - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- ↑ Ulrich Theobald. "Chinese History - Bohai 渤海 (Parhae)". www.chinaknowledge.de. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- ↑ Old Book of Tang, vol. 199, part 2.

- ↑ 萧国亮 (2007-01-24). "明代汉族与女真族的马市贸易". 艺术中国(ARTX.cn). p. 1. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ Serruys 1955, p. 22.

- ↑ "U.S. Senate Report Highlights Chinese View of Korean Kingdoms". english.chosun.com. Retrieved 2013-03-22.

- ↑ "US to publish report on Chinese distortion of Korean history: sources.". www.koreatimes.co.kr. Retrieved 2013-03-22.

- ↑ "Ethnic Groups". china.org.cn. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ↑ New Book of Tang, Original: 渤海,本粟末靺鞨附高丽者,姓大氏. Link

- ↑ “渤海本粟末靺鞨,至其酋祚荣立国,自号震旦。先天中,始去靺鞨号,专称渤海”。

- ↑ 天皇二年(698年),大祚荣始建渤海国,其国延袤二千里,无州县馆驿,处处有村里,皆靺鞨部落。其百姓者 靺鞨多,土人少,皆以土人为村长.

- ↑ Book of Jin, chapter 1, p. 25 of the Beijing Zhonghua shuju edition.

- ↑ 周恩来总理谈中朝关系(摘自《外事工作通报》1963年第十期)1963年6月28日,周恩来总理接见朝鲜科学院代表团时,谈中朝关系 “朝鲜民族进驻朝鲜半岛和东北大陆以来,长期生活在那里。这是发掘于辽河和松花江流域及图们江和鸭绿江流域的许多遗物和碑文等史料所证明的,在许多朝鲜文献中也遗留了那些历史痕迹。” , “镜泊湖附近留有渤海遗迹,曾是渤海的首府。在这里出土的文物也证明那里也曾是朝鲜民族的一个支派。”

- ↑ Mark Byington (2004). "The War of Words Between South Korea and China Over An Ancient Kingdom: Why Both Sides Are Misguided".

- ↑ Ross Terrill, The New Chinese Empire: And What it Means for the United States (2004), pp. 198-200 (ISBN 9780465084135).

- ↑ "한국학중앙연구원" (PDF). Review.aks.ac.kr. 2009-01-19. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- 1 2 Leonid A. Petrov (2004). "Restoring the Glorious Past: North Korean Juche Historiography and Goguryeo". The Review of Korean Studies. 7 (3): 231–252.

- ↑ "Российская наука и мир (дайджест) - Март 2004 г. (часть 2)". Prometeus.nsc.ru. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ↑ The New Chinese Empire: And What It Means For The United States - Ross Terrill - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ↑ Archived January 9, 2006, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "발해 - Daum 백과사전" (in Korean). Enc.daum.net. Retrieved 2012-09-12.

- ↑ Pozzi & Janhunen & Weiers 2006, p. 109

Further reading

- Mark Byington (October 7–8, 2004). "A Matter of Territorial Security: Chinese Historiographical Treatment of Koguryo in the Twentieth Century". International Conference on Nationalism and Textbooks in Asia and Europe, Seoul, The Academy of Korean Studies.

- 孫玉良 (1992). 渤海史料全編. 吉林文史出版社 ISBN 978-7-80528-597-9

- F.W. Mote (1999). Imperial China, 900-1800. Harvard University Press. pp. 49, 61–62. ISBN 0-674-01212-7.

- Pozzi, Alessandra; Janhunen, Juha Antero; Weiers, Michael, eds. (2006). Tumen Jalafun Jecen Aku: Manchu Studies in Honour of Giovanni Stary. Volume 20 of Tunguso Sibirica. Contributor Giovanni Stary. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 344705378X. Retrieved 1 April 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Balhae. |

- Britannica Concise Encyclopedia

- Columbia Encyclopedia

- U.S. Library of Congress: Country Studies

- Metropolitan Museum of Art

- Stearns, Peter N (ed.). Encyclopedia of World History (6 ed.). The Houghton Mifflin Company/ Bartleby.com.

the state of Parhae (or Bohai in Chinese)

- (Korean) Han's Palhae of Korea 한규철의 발해사 연구실