Pleistocene rewilding

Pleistocene rewilding is the advocacy of the reintroduction of descendants of Pleistocene megafauna, or their close ecological equivalents. An extension of the conservation practice of rewilding, which involves reintroducing species to areas where they became extinct in recent history (hundreds of years ago or less).[1]

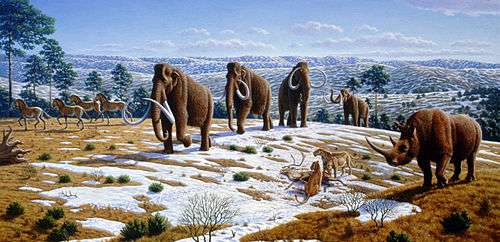

Towards the end of the Pleistocene era (roughly 13,000 to 10,000 years ago), nearly all megafauna of Europe, as well as South, Central and North America, dwindled towards extinction, in what has been referred to as the Quaternary extinction event. With the loss of large herbivores and predator species, niches important for ecosystem functioning were left unoccupied.[2] In the words of the biologist Tim Flannery, "ever since the extinction of the megafauna 13,000 years ago, the continent has had a seriously unbalanced fauna". This means, for example, that the managers of national parks in North America have to resort to culling to keep the population of ungulates under control.[3]

Paul S. Martin (originator of the Pleistocene overkill hypothesis[4]) states that present ecological communities in North America do not function appropriately in the absence of megafauna, because much of the native flora and fauna evolved under the influence of large mammals.[5]

Ecological and evolutionary implications

Research shows that species interactions play a pivotal role in conservation efforts. Communities where species evolved in response to Pleistocene megafauna (but now lack large mammals) may be in danger of collapse.[6][7] Most living megafauna are threatened or endangered; extant megafauna have a significant impact on the communities they occupy, which supports the idea that communities evolved in response to large mammals. Pleistocene rewilding could "serve as additional refugia to help preserve that evolutionary potential" of megafauna.[7] Reintroducing megafauna to North America could preserve current megafauna, while filling ecological niches that have been vacant since the Pleistocene.[8]

Possible fauna for reintroduction

The Pleistocene rewilding project aims at the promotion of extant fauna and the reintroduction of extinct genera in the southwestern United States. Native fauna are the first genera for reintroduction. The Bolson tortoise was widespread during the Pleistocene era, and continued to be common during the Holocene epoch until recent times. Its reintroduction from northern Mexico would be a necessary step to recreate the soil humidity present in the Pleistocene, which would support grassland and extant shrub-land and provide the habitat required for the herbivores set for reintroduction. However, to be successful, ecologists will support fauna already present in the region.

The pronghorn, which is extant in most of the US southwest after almost becoming extinct, is a candidate for the revival of the ancient ecosystem. The pronghorn are native to the region, which once supported large numbers of the species and extinct relatives from the same genus. It would occupy the more arid and mountainous ecosystems within the assigned area.

The plains bison numbered in the millions during the Pleistocene era, until European settlers drove them to near-extinction in the late 19th century. The bison has made a recovery in many regions of its former range, and is involved in several local rewilding projects across the Midwestern United States.

Bighorn sheep and mountain goats are already present in the surrounding mountainous areas and therefore should not pose a problem in rewilding more mountainous areas. Reintroducing extant species of deer to the more forested areas of the region would be beneficial for the ecosystems they occupy, providing rich nutrients for the forested regions and helping to maintain them. These species include white-tailed and mule deer.

Herbivorous species considered beneficial for the regional ecosystems include the collared peccary, a species of New World wild pig that was abundant in the Pleistocene. Although this species (along with the flat-headed and long-nosed peccaries) are extinct in many regions of North America, their relatives survive in Central and South America and the collared peccary can still be found in southern Arizona and Texas.

The horse, which is today extant as the mustang is, in fact, a native species reintroduced by the Spanish in the 15th century. Horses originated in North America and spread to Asia via the Ice Age land bridge, but became extinct in their evolutionary homeland alongside the mammoth and ground sloth. The Pleistocene grasslands of North America were the birthplace of the modern horse, and by extension the wild horse. The only remaining species of wild horse is a part of the prairie ecosystem and grazes alongside bison. The plains were home to an equid resembling a zebra, called the Hagerman horse; this could be represented by grant's zebra or Grevy's zebra. It would be introduced into the Great Plains from Africa as part of the project. The mountainous region was also once home to the extinct Yukon wild horse, whose close relative (the onager) survives in central Asia today, and can be reintroduced to boost biodiversity in the more arid regions of the rewilding area.

Alongside the wild horse, camels evolved in the drier regions of North America. Proof of this can be seen in the camelids of South America: the llama, alpaca, guanaco and vicuna. North America, therefore, links the South American camelids with those of the Old World (the dromedary and Bactrian camel). Pleistocene rewilding suggests that the closest relatives of the North American species of camel (Camelops) be reintroduced. The best candidates would be the dromedary for the arid desert regions and the guanaco and/or vicuna in the arid mountain regions, but there have been suggestions of breeding and wilding the fertile hybrid camelids (cama).

During the Pleistocene, two species of tapir existed in North America: the California and Florida tapirs. They became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene era, but their relatives survive in South America. The mountain tapir would be an excellent choice for rewilding humid areas, such as those near lakes and rivers. The mountain tapir is the only extant non-tropical species of tapir.

During the Pleistocene, large populations of Proboscideans lived in North America, such as the Columbian mammoth and the American mastodon. The mastodons all became extinct at the end of the Pleistocene era, as did the mammoths of North America. However, an extant relative of the mammoth is the Asian elephant. It now resides only in tropical southeastern Asia, but the fossil record shows that it was much more widespread, living in temperate northern China as well as the Middle East (an area bearing an ecological similarity to the southwestern United States). The Asian elephant is, therefore, a good candidate for the Pleistocene rewilding project. It would probably best be suited to occupy the same humid areas as the tapir, as well as dense forest regions where it would cause soil regeneration and control the spread of forests. Meanwhile, the African elephant may be the best extant candidate to refill the niche left empty with the extinction of the mastodon.[3]

During the Pleistocene era, North, Central and South America were populated with a group of large animals that moved north as part of the Great American Interchange caused by the junction of the North and South American continents. Today, species such as the ground sloth and glyptodon are extinct, although a few "dwarf" species of sloth survived in remote Caribbean-island forests until a few thousand years ago. Their close relatives, the tree sloths and armadillos, are a remnant of this once-diverse group of mammals. The reintroduction of armadillos (such as the nine-banded armadillo and the giant armadillo) could help regenerate soils in the arid and prairie regions of the rewilding project.

Pleistocene America boasted a wide variety of dangerous carnivores (most of which are extinct today), such as the short-faced bear, saber-toothed cats (e.g. Homotherium), the American lion, dire wolf, American cheetah and (possibly) the terror bird. Some carnivores and omnivores survived the end of the Pleistocene era and were widespread in North America until Europeans arrived, such as grizzly bears, mountain lions, jaguars, grey and red wolves, bobcats, and coyotes.[9] The African cheetah would make a great choice for rewilding, keeping the population of pronghorns in check. Jaguars could be reintroduced back to North America to control populations of prey animals. Some of the larger cats such as the African lion could act as a proxy for the Pleistocene American lion, they could be introduced to keep the numbers of herds of American bison in check.

Back then, there were also native new world monkeys of North America. Some species including capuchin monkeys, spider monkeys, and/or squirrel monkeys could be reintroduced to warm and humid parts of North America, including Florida, etc, to fill the niche left behind be the native monkeys.link

Recreating a lost ecosystem

In order for a functioning and balanced ecosystem to exist, there must be carnivores that prey on the herbivores. In the mountains, the reintroduction of the mountain lion is necessary to keep mountainous herbivores, such as the camelids, asses and mountain goats, under control.

In the forest surrounding them, the reintroduction of the jaguar (which roamed much of southwestern America until early 20th century) will control the populations of animals such as deer, tapirs and peccary. Alongside the jaguar will be the grizzly bear, an omnivore that was once distributed across North America but now survives only in the far north of the US and much of western and northwestern Canada. In heavily forested areas, the Siberian tiger and dhole will be introduced to control the populations of deer, wild asses, camels, bighorns, and mountain goats.

The terror birds' closest living relatives are the much smaller seriemas. Ecologically, the seriema is the South American counterpart of the secretary bird.

In arid regions, the Old World cheetah could be introduced to control the population of pronghorn, the fastest-running herbivore on earth (it can run so fast because it was once hunted by the American cheetah). The American cheetah was more closely related to the mountain lion, but evolved in a similar way to the Old World cheetah (an example of convergent evolution).

Reintroduced into its ancient environment, the grey wolf will spread across all ecosystems and compete for prey with all other predators; it may once again be seen hunting camels in arid regions, and bison on the grassy prairies of the Great Plains.

The final (and most-controversial) aspect of the rewilding project is the reintroduction of lions to the American southwest. Whilst many consider the lion to be strictly an African species, this was not always true. The lion was, in fact, one of the most widespread of all megafauna (certainly of the carnivores). The lion once ranged from Africa through Pleistocene Europe and Asia, across Beringia and down through North America to Argentina in South America. A relict remnant of that distribution across the world is still found in India, where the Asiatic lion still survives in a small sanctuary in the Gir Forest National Park. In Europe and northern Asia it existed as the cave lion, and in the Americas as the American lion. The American lion once hunted in prides across the grasslands of Pleistocene North America, taking down bison and wild horses as their African equivalents take down wildebeest and zebra. The reintroduction of lions is, however, the end of a long line of reintroductions, and will only have realistic prospects of occurring if all goes well with the others first.

The Pleistocene parks idea was first suggested for Arctic and South American ecosystems, and was less publicized.[6][10] Mauro Galetti suggested that several plant species in South America lost their major megafauna seed dispersers at the end of the Pleistocene.[6] Secondary seed dispersal, water and indigenous people were responsible for maintaining the seed-dispersal process over the past 10,000 years.[8][11] Therefore, rewilding South American savannas will establish lost seed-dispersal services and also control unburned vegetation (due to a lack of megaherbivores). Brazilian savannas burn and release tons of carbon dioxide to the atmosphere yearly. Asian elephants, horses, llamas and other large mammals may be used to control fires.

Implementation

The reintroduction of Bolson tortoise, equids (mustangs and burros) and camelids (dromedary) has already begun. Muskoxen roam areas of Europe and Asia last grazed during Rome's heyday, and bison herds thrive in subarctic Canada and Alaska. As of 2011, there are no active plans to reintroduce more exotic megafauna, such as elephants, cheetahs or lions, due to the controversial nature of these reintroductions.

The southwestern United States and the Brazilian savanna are the most suitable parts of North and South America where Pleistocene rewilding could be implemented. Besides fencing off large land tracts, a natural setting would be maintained, in which predator-prey dynamics would take their course uninterrupted.[6] The long-term plan is for an "ecological history park encompassing thousands of square miles in economically depressed parts of the Great Plains".[7]

The Bolson tortoise will expand its prehistoric population and thrive in places like Texas. Feral horses will be encouraged to breed and multiply, and will be proxies for extinct equids. Camelids (of the genera Camelus, Lama, and Vicugna) will serve as proxies for the approximately six extinct camel species in North America. The African cheetah will serve for the American cheetah, while the African lion will serve for the American lion. The elephant species will represent the five species of mammoth, mastodon, and gomphothere which thrived in North America.

Other animals that can be used for the project might include: mountain tapir, Baird's tapir, and South American tapir (formerly part of a widespread Holarctic family); Saiga antelope (a Pleistocene resident of the Alaskan steppe, now found only in Central Asia); Capybara (which had its relatives that lived in North America); and the dhole (which thrived throughout North America and Eurasia during the Pleistocene). Scientific evidence points to the Siberian tiger crossing the Bering Strait into Alaska during the Pleistocene.

Criticism

The main criticism of the Pleistocene rewilding is that it is unrealistic to assume that communities today are functionally similar to their state 10,000 years ago. Opponents argue that there has been more than enough time for communities to evolve in the absence of mega-fauna, and thus the reintroduction of large mammals could thwart ecosystem dynamics and possibly cause collapse. Under this argument, the prospective taxa for reintroduction are considered exotic and could potentially harm natives of North America through invasion, disease, or other factors.[1]

Opponents of the Pleistocene rewilding present an alternative conservation program, in which more recent North American natives will be reintroduced into parts of their native ranges where they became extinct during historical times.[1] Another way of rewilding Americas, Asia, etc. is by using de-extinction, bringing extinct species back to life through cloning.[12]

Pleistocene rewilding in Europe

This plan was considered by Josh Donlan and Jens-C. Svenning, and involves (as in rewilding North America) creating a Pleistocene habitat in portions of Europe.[12] Svenning claims that "Pleistocene Rewilding can be taken for consideration outside of North America". Incidentally, an independent "Rewilding Europe" initiative was established in the Netherlands in 2011, with the western Iberian Peninsula, Velebit, the Danube delta and the eastern and southern Carpathians as particular targets.[13] The proxies which may be used for this project(s) are:

Animals which have been already introduced Fallow deer, reintroduced from Anatolia in most parts of Europe already in Ancient times. Mouflon, reintroduced for hunting purposes in the continent from the island populations of Corsica and Sardinia (originated in turn by introductions from the Middle East during the Neolithic period). Musk ox, reintroduced in 1976 to Russia (Taimyr Peninsula and Wrangel Island) and Scandinavia.[14] Northern bald ibis, extinct in southern Europe during the Modern Age, has reintroduction projects underway in Austria and Spain. European bison, saved from extinction in zoos in the early 20th century and reintroduced in several places of Eastern Europe. American bison in Askania Nova, Ukraine, a proxy for the Pleistocene steppe bison. Expanding populations Wisent Alpine ibex Spanish ibex Chamois Moose Wolf Eurasian lynx Iberian lynx Brown bear European mink Mediterranean monk seal European beaver Osprey White-tailed eagle Griffon vulture Eurasian black vulture Eurasian eagle owl

Northern Siberia

The aim of Siberian Pleistocene rewilding is to recreate the ancient mammoth steppe by reintroducing megafauna. The first step was the successful reintroduction of musk oxen on the Taymyr Peninsula and Wrangel island. In 1988, researcher Sergey Zimov created Pleistocene Park – a nature reserve in northeastern Siberia for full-scale megafauna rewilding.[13] Reindeer, Siberian roe deer and moose were already present; Yakutian horses, muskox, Altai wapiti and wisent were reintroduced. Reintroduction is also planned for yak, Bactrian camels, snow sheep, Saiga antelope, and Siberian tigers. The wood bison, closest relative of the ancient bison which became extinct in Siberia 1,000 to 2,000 years ago, is an important species for the ecology of Siberia. In 2006, 30 bison calves were flown from Edmonton, Alberta to Yakutsk. Now they live in the government-run reserve of Ust'-Buotama.

Animals which have been already introduced Fallow deer, reintroduced from Anatolia in most parts of Europe already in Ancient times. Mouflon, reintroduced for hunting purposes in the continent from the island populations of Corsica and Sardinia (originated in turn by introductions from the Middle East during the Neolithic period). Musk ox, reintroduced in 1976 to Russia (Taimyr Peninsula and Wrangel Island) and Scandinavia.[14] Northern bald ibis, extinct in southern Europe during the Modern Age, has reintroduction projects underway in Austria and Spain. European bison, saved from extinction in zoos in the early 20th century and reintroduced in several places of Eastern Europe. American bison in Askania Nova, Ukraine, a proxy for the Pleistocene steppe bison. Expanding populations Wisent Alpine ibex Spanish ibex Chamois Moose Wolf Eurasian lynx Iberian lynx Brown bear European mink Mediterranean monk seal European beaver Osprey White-tailed eagle Griffon vulture Eurasian black vulture Eurasian eagle owl

Animals that have been already introduced

- Musk ox (became extinct in Siberia about 2000 years ago, but has been reintroduced in Taimyr Peninsula and on Wrangel Island)[14]

- Wood bison (A group of 30 wood bison were introduced to Yakutia in 2006 as a proxy for the extinct steppe bison)[15]

- Yakutian horse (A group of these horses were brought to Pleistocene Park to replace the extinct horses)

Considered for reintroduction

- Bactrian camel (could act as a proxy for Pleistocene camel species)

- Dromedary camel (could act as a proxy for Pleistocene camel species)

- Elk (could act as a proxy for the extinct species of large fast-moving Asian deer)

- Saiga antelope (occurred in many parts of Siberia until recently, now restricted to Chyornye Zemli Nature Reserve)

- Siberian roe deer (could be brought back by both introductions and migrations)

- Siberian tiger (occurred up to Beringia during the late Pleistocene, now restricted to southeastern Siberia)[16]

- Snow sheep (could be brought back to many parts of Siberia through both introductions and migrations)

- Yak (could be brought back to its former range in Siberia such as Pleistocene park)

Island landmasses

Megafauna that arose on insular landmasses were especially vulnerable to human influence because they evolved in isolation from other landmasses, and thus were not subjected to the same selection pressures that surviving fauna were subject to, and many forms of insular megafauna were wiped out after the arrival of humans. Therefore, scientists have suggested introducing closely related taxa to replace the extinct taxa. This is being done on several islands, with replacing closely related or ecologically functional giant tortoises to replace extinct giant tortoises.[17] For example, the Aldabra giant tortoise has been suggested for replacing the extinct Malagasy giant tortoises,[18][19] and Malagasy radiated tortoises have been introduced to Maritius to replace the tortoises that were present there.[20] However, the usage of tortoises in rewilding experiments have not been limited to replacing extinct tortoises. At the Makauwahi Cave Reserve in Hawaii, exotic tortoises are being used as a replacement for the extinct moa-nalo,[21] a large flightless duck hunted to extinction by the first Polynesians to reach Hawaii. The grazing habits of these tortoises control and reduce the spread of invasive plants, and promote the growth of native flora.[22]

Australia

Expanding populations

- Koala

- Common wombat

- Northern hairy-nosed wombat

- Southern hairy-nosed wombat

- Tasmanian devil (possible reintroduction to mainland Australia)

- Eastern wallaroo

- Southern cassowary

- Australian sea lion (possible reintroduction to Bass Strait)

Extant outside Australia

- Western long-beaked echidna (specimen collected in the early 20th century in the Kimberley region of Western Australia, a possible relic population continues to exist there)

- Dwarf cassowary

- Komodo dragon (also serves as proxy for Megalania)

- Southern elephant seal (colony wiped out by sealers on King Island during the 19th century)

- New Zealand pigeon (endemic race was exterminated on Lord Howe Island)

- New Zealand kaka (proxy for the Norfolk kaka that was exterminated on Norfolk Island)

See also

- De extinction

- Endangered species

- List of introduced species

- Mustang

- Pleistocene Park

- Quaternary extinction event

References

- 1 2 3 Rubenstein, D.R.; D.I. Rubenstein; P.W. Sherman; T.A. Gavin (2006). "Pleistocene Park: Does re-wilding North America represent sound conservation for the 21st century?" (PDF). Retrieved 28 July 2008.

- ↑ Janzen, Daniel H.; Paul S. Martin (1982-01-01). "Neotropical Anachronisms: The Fruits the Gomphotheres Ate" (PDF). Science. 215 (4528): 19–27. doi:10.1126/science.215.4528.19. PMID 17790450. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- 1 2 Tim Flannery (2001), The Eternal Frontier: An Ecological History of North America and its Peoples, ISBN 1-876485-72-8, pp. 344--346

- ↑ Martin, Paul (22 October 1966). "Africa and Pleistocene Overkill". Nature. 212 (5060): 339–342. doi:10.1038/212339a0.

- ↑ Martin, P. S. (2005). Twilight of the Mammoths: Ice Age Extinctions and the Rewilding of America. University of California Press. ISBN 0520231414. OCLC 58055404. Retrieved 2014-11-11.

- 1 2 3 4 Galetti, M. (2004). "Parks of the Pleistocene: Recreating the cerrado and the Pantanal with megafauna". Natureza e Conservação. 2 (1): 93–100.

- 1 2 3 Donlan, C.J.; et al. (2006). "Pleistocene Rewilding: An Optimistic Agenda for Twenty-First Century Conservation" (PDF). The American Naturalist. 168: 1–22. doi:10.1086/508027.

- 1 2 Donatti, C.I.; M. Galetti; M.A. Pizo; P.R. Guimarães Jr. & P. Jordano (2007). "Living in the land of ghosts: Fruit traits and the importance of large mammals as seed dispersers in the Pantanal, Brazil". In Dennis, A.; R. Green; E.W. Schupp & D. Wescott. Frugivory and seed dispersal: theory and applications in a changing world. Wallingford, UK: Commonwealth Agricultural Bureau International. pp. 104–123.

- ↑ Conservation Magazine, July 2008 Retrieved 2011-05-18.

- ↑ Zimov, Sergey A. (2005-05-06). "Pleistocene Park: Return of the Mammoth's Ecosystem". Science. 308 (5723): 796–798. doi:10.1126/science.1113442. PMID 15879196. Retrieved 29 July 2008.

- ↑ Guimarães Jr., P.; M. Galetti & P. Jordano (2008). "Seed dispersal anachronisms: Rethinking the fruits extinct megafauna ate". PLoS ONE. 3 (In Press): e1745. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0001745. PMC 2258420

. PMID 18320062.

. PMID 18320062. - ↑ "De-Extinction". nationalgeographic.com. 15 March 2015.

- ↑ "Pleistocene Park: Restoration of the Mammoth Steppe Ecosystem".

- ↑ Gunn, A. & Forchhammer, M. (2008). "Ovibos moschatus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2008. International Union for Conservation of Nature. Retrieved 31 March 2009. Database entry includes a brief justification of why this species is of least concern.

- ↑ http://www.lhnet.org/re-introducing-wood-bison-2/

- ↑ Vratislav Mazák: Der Tiger. Westarp Wissenschaften; Auflage: 5 (April 2004), unveränd. Aufl. von 1983 ISBN 3-89432-759-6 (S. 196)

- ↑ Hansen, Dennis M.; Donlan, C. Josh; Griffiths, Christine J.; Campbell, Karl J. (1 April 2010). "Ecological history and latent conservation potential: large and giant tortoises as a model for taxon substitutions". Ecography. 33 (2): 272–284. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0587.2010.06305.x – via Wiley Online Library.

- ↑ "Rewilding Giant Tortoises in Madagascar".

- ↑ "Imported Tortoises Could Replace Madagascar's Extinct Ones".

- ↑ "Rewilding".

- ↑ "Makauwahi Cave Reserve".

- ↑ TEDx Talks (11 April 2013). "Rewilding, Ecological Surrogacy, and Now... De-extinction?: David Burney at TEDxDeExtinction" – via YouTube.

External links

- Mauro Galetti

- Paulo Guimarães Jr.

- Pedro Jordano

- The Rewilding Institute

- C. Josh Donlan

- Re-wilding North America

- Rewilding Megafauna: Lions and Camels in North America?

- Pleistocene Park Could Solve Mystery of Mammoth's Extinction

- Pleistocene Rewilding merits serious consideration also outside North America for Rewilding Europe

- Megafauna: First Victims of the Human-Caused Extinction