Radar astronomy

Radar astronomy is a technique of observing nearby astronomical objects by reflecting microwaves off target objects and analyzing the reflections. This research has been conducted for six decades. Radar astronomy differs from radio astronomy in that the latter is a passive observation and the former an active one. Radar systems have been used for a wide range of solar system studies. The radar transmission may either be pulsed or continuous.

The strength of the radar return signal is proportional to the inverse fourth-power of the distance. Upgraded facilities, increased transceiver power, and improved apparatus have increased observational opportunities.

Radar techniques provide information unavailable by other means, such as testing general relativity by observing Mercury[1] and providing a refined value for the astronomical unit.[2] Radar images provide information about the shapes and surface properties of solid bodies, which cannot be obtained by other ground-based techniques.

Relying upon high powered terrestrial radars (of up to one MW[3]) radar astronomy is able to provide extremely accurate astrometric information on the structure, composition and movement of solar objects.[4] This aids in forming long-term predictions of asteroid-Earth impacts, as illustrated by the object 99942 Apophis. In particular, optical observations measure where an object appears in the sky, but cannot measure the distance with great accuracy (relying on Parallax becomes more difficult when objects are small or poorly illuminated). Radar, on the other hand, directly measures the distance to the object (and how fast it is changing). The combination of optical and radar observations normally allows the prediction of orbits at least decades, and sometimes centuries, into the future.

There are two radar astronomy facilities that are in regular use, the Arecibo Planetary Radar and the Goldstone Solar System Radar.

Advantages

- Control of attributes of the signal [i.e., the waveform's time/frequency modulation and polarization]

- Resolve objects spatially;

- Delay-Doppler measurement precision;

- Optically opaque penetration;

- Sensitive to high concentrations of metal or ice.

Disadvantages

The maximum range of astronomy by radar is very limited, and is confined to the Solar system. This is because the signal strength drops off very steeply with distance to the target, the small fraction of incident flux that is reflected by the target, and the limited strength of transmitters.[5] The distance to which the radar can detect an object is proportional to the square root of the object's size, due to the one-over-distance-to-the-fourth dependence of echo strength. Radar could detect something ~1 km across a large fraction of an AU away, but at 8-10 AU, the distance to Saturn, we need targets at least hundreds of kilometers wide. It is also necessary to have a relatively good ephemeris of the target before observing it.

History

The moon is comparatively close and was detected by radar soon after the invention of the technique in 1946.[6][7] Measurements included surface roughness and later mapping of shadowed regions near the poles.

The next easiest target is Venus. This was a target of great scientific value, since it could provide an unambiguous way to measure the size of the astronomical unit, which was needed for the nascent field of interplanetary spacecraft. In addition such technical prowess had great public relations value, and was an excellent demonstration to funding agencies. So there was considerable pressure to squeeze a scientific result from weak and noisy data, which was accomplished by heavy post-processing of the results, utilizing the expected value to tell where to look. This led to early claims (from Lincoln Laboratory, Jodrell Bank, and Vladimir A. Kotelnikov of the USSR) which are now known to be incorrect. All of these agreed with each other and the conventional value of AU at the time.[2]

The first un-ambiguous detection of Venus was made by Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) on 10 March 1961. A correct measurement of the AU soon followed. Once the correct value was known, other groups found echos in their archived data that agreed with these results.[2]

The following is a list of planetary bodies that have been observed by this means:

- Mars - Mapping of surface roughness from Arecibo Observatory. The Mars Express mission carries a ground-penetrating radar.

- Mercury - Improved value for the distance from the earth observed (GR test). Rotational period, libration, surface mapping, esp. of polar regions.

- Venus - first radar detection in 1961. Rotation period, gross surface properties. The Magellan mission mapped the entire planet using a radar altimeter.

- Jupiter System - Galilean satellites

- Saturn System - Rings and Titan from Arecibo Observatory, mapping of Titan's surface and observations of other moons from the Cassini spacecraft.

- Earth - numerous airborne and spacecraft radars have mapped the entire planet, for various purposes. One example is the Shuttle Radar Topography Mission, which mapped the entire Earth at 30 m resolution.

Asteroids and comets

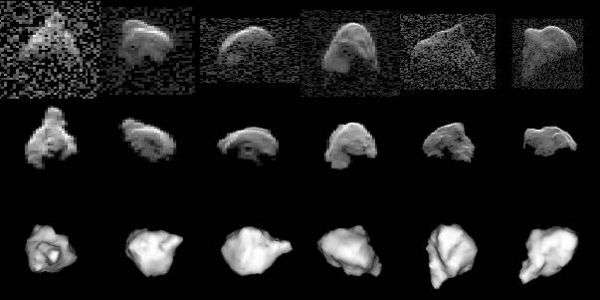

Radar provides the ability to study shape, size and spin state of asteroids and comets from the ground. Radar imaging has produced images with up to 7.5-m resolution. With sufficient data, the size, shape, spin and radar albedo of the target asteroids can be extracted.

Only 19 comets have been studied by radar,[8] including 73P/Schwassmann-Wachmann. There have been radar observations of 612 Near-Earth asteroids and 138 Main belt asteroids.[8]

See also

- Arecibo Observatory

- Five-hundred-meter Aperture Spherical Telescope

- Goldstone Deep Space Communications Complex

- RT-70

- Pluton

- Deep Space Network

- Radar

- Radar imaging

- 6489 Golevka

- 4179 Toutatis

References

- ↑ Anderson, John D.; Slade, Martin A.; Jurgens, Raymond F.; Lau, Eunice L.; Newhall, X. X.; Myles, E. (July 1990). Radar and spacecraft ranging to Mercury between 1966 and 1988. IAU, Asian-Pacific Regional Astronomy Meeting, 5th, Proceedings (Held July 16–20, 1990). 9. Sydney, Australia: Astronomical Society of Australia. p. 324. Bibcode:1991PASAu...9..324A. ISSN 0066-9997.

- 1 2 3 Andrew J. Butrica (1996). "NASA SP-4218: To See the Unseen - A History of Planetary Radar Astronomy". NASA. Archived from the original on 2007-08-23. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- ↑ "Arecibo Radar Status". Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ↑ Ostro, Steven (1997). "Asteroid Radar Research Page". JPL. Retrieved 22 December 2012.

- ↑ Hey, J. S. (1973). The Evolution of Radio Astronomy. Histories of Science Series. 1. Paul Elek (Scientific Books).

- ↑ J. Mofensen, Radar echoes from the moon, Electronics, vol. 19, pp. 92-98; April, 1946

- ↑ Z. Bay, "Reflection of microwaves from the moon," Hung. Acta Phys., vol. 1, pp. 1-22; April, 1946.

- 1 2 "Radar-Detected Asteroids and Comets". NASA/JPL Asteroid Radar Research. Retrieved 2016-04-25.

External links

- How radio telescopes get images of asteroids

- "Planetary Radar at Arecibo Observatory". NAIC. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- "Goldstone Solar System Radar". JPL. Retrieved 2010-09-28.

- Dr. Steven J. Ostro & Dr. Lance A. M. Benner (2007). "JPL Asteroid Radar Research". Caltech. Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- "Radar Astronomy and Space Radio Science". Retrieved 2008-05-15.

- Dr. Jean-Luc Margot. "Introduction to Asteroid Radar Astronomy". UCLA. Retrieved 2013-08-02.

- BINARY AND TERNARY NEAR-EARTH ASTEROIDS DETECTED BY RADAR