Photon sphere

A photon sphere is a spherical region of space where gravity is strong enough that photons are forced to travel in orbits. The radius of the photon sphere, which is also the lower bound for any stable orbit, is:

(where r is the radius, in meters, G is the gravitational constant, M is the mass in kg, and c is the speed of light in vacuum) which is one and one-half times the Schwarzschild radius.

This equation entails that photon spheres can only exist in the space surrounding an extremely compact object (a black hole or possibly a neutron star[1]).

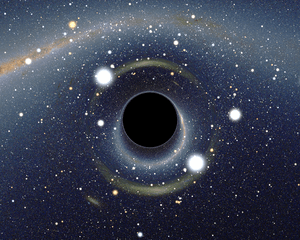

As photons approach the event horizon of a black hole, those with the appropriate energy avoid being pulled into the black hole by traveling in a nearly tangential direction known as an exit cone. A photon on the boundary of this cone does not possess the energy to escape the gravity well of the black hole. Instead, it orbits the black hole. These orbits are rarely stable in the long term.

The photon sphere is located farther from the center of a black hole than the event horizon and ergosphere. Within a photon sphere, it is possible to imagine a photon that begins at the back of your head, orbiting the black hole, only then to be intercepted by your eyes, allowing you to see the back of your head. For non-rotating black holes, the photon sphere is a sphere of radius 3/2 Rs, where Rs denotes the Schwarzschild radius (the radius of the event horizon) - see below for a derivation of this result. There are no stable free fall orbits that exist within or cross the photon sphere. Any free fall orbit that crosses it from the outside spirals into the black hole. Any orbit that crosses it from the inside escapes permanently. No unaccelerated orbit with a semi-major axis less than this distance is possible, but within the photon sphere, a constant acceleration will allow a spacecraft or probe to hover above the event horizon.

Another property of the photon sphere is centrifugal force (nb: not centripetal) reversal.[2] Outside the photon sphere, the faster one orbits the greater the outward force one feels. Centrifugal force falls to zero at the photon sphere, including non-freefall orbits at any speed, i.e. you weigh the same no matter how fast you orbit, and becomes negative inside it. Inside the photon sphere the faster you orbit the greater your felt weight or inward force. This has serious ramifications for the fluid dynamics of inward fluid flow.

A rotating black hole has two photon spheres. As a black hole rotates, it drags space with it. The photon sphere that is closer to the black hole is moving in the same direction as the rotation, whereas the photon sphere further away is moving against it. The greater the angular velocity of the rotation of a black hole, the greater the distance between the two photon spheres. Since the black hole has an axis of rotation, this only holds true if approaching the black hole in the direction of the equator. If approaching at a different angle, such as one from the poles of the black hole to the equator, there is only one photon sphere. This is because approaching at this angle the possibility of traveling with or against the rotation does not exist.

Derivation for a Schwarzschild black hole

Since a Schwarzschild black hole has spherical symmetry, all possible axes for a circular photon orbit are equivalent, and all circular orbits have the same radius.

This derivation involves using the Schwarzschild metric, given by:

For a photon traveling at a constant radius r (i.e. in the Φ-coordinate direction), . Since it is a photon (a "light-like interval"). We can always rotate the coordinate system such that is constant, .

Setting ds, dr and dθ to zero, we have:

Re-arranging gives:

where Rs is the Schwarzschild radius.

To proceed we need the relation . To find it, we use the radial geodesic equation

Non vanishing -connection coefficients are , where .

We treat photon radial geodesics with constant r and , therefore

.

Substituting it all into the radial geodesic equation (the geodesic equation with the radial coordinate as the dependent variable), we obtain

Comparing it with obtained previously, we have:

where we have inserted radians (imagine that the central mass, about which the photon is orbiting, is located at the centre of the coordinate axes. Then, as the photon is travelling along the -coordinate line, for the mass to be located directly in the centre of the photon's orbit, we must have radians).

Hence, rearranging this final expression gives:

which is the result we set out to prove.

Spherical photon orbits around a Kerr black hole

In contrast to a Schwarzschild black hole, a Kerr (spinning) black hole does not have spherical symmetry, but only an axis of symmetry, which has profound consequences for the photon orbits. A circular orbit can only exist in the equatorial plane, and there are two of them (prograde and retrograde), with different radii. All other constant-radius orbits have more complicated paths that oscillate in latitude about the equator.[3]

References

- General Relativity: An Introduction for Physicists

- ↑ Properties of ultracompact neutron stars

- ↑ Abramowicz, Marek. "Centrifugal-force reversal near a Schwarzschild black hole". Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society, Vol. 245, NO.4/AUG15, P. 720, 1990.

- ↑ Teo, Edward (2003). "Spherical Photon Orbits Around a Kerr Black Hole" (PDF). General Relativity and Gravitation. 35 (11): 1909–1926. Bibcode:2003GReGr..35.1909T. doi:10.1023/A:1026286607562. ISSN 0001-7701.

External links

- Step by Step into a Black Hole

- Virtual Trips to Black Holes and Neutron Stars

- Guide to Black Holes

- Spherical Photon Orbits Around a Kerr Black Hole