Philanthropy in the United States

The United States has a history of philanthropy that possibly dates back to the early settlement by Europeans.

History

"Voluntary Associations"

What emerged in this way was a culture of collaboration. Colonial society was built by volunteers, or as Alexis de Tocqueville later referred to them, "voluntary associations"—which is to say, "private initiatives for public good, focusing on quality of life". He observed that they permeated American life, were a distinguishing feature of the American character and culture, and a key to American democracy. Americans, he said, did not rely on others—government, an aristocracy, or the church—to solve their public problems; rather, they did it themselves, through voluntary associations, which is to say, philanthropy, which was characteristically democratic.

One of the first, if not the first of these, was also one of the first American governments: the Mayflower Compact of 1620. The Pilgrims, still offshore but in American waters as it were, declared that they "solemnly and mutually, in the Presence of God and one another, combine ourselves together into a civil Body Politick, for our better Ordering and Preservation." The first corporation, Harvard College (1636), also in the Massachusetts Bay Colony, was a philanthropic voluntary association created to train young men for the clergy

As was typical in that period, American philanthropic associations had ideological dimensions. Three of the leading English colonies—Massachusetts, Pennsylvania and Virginia—were styled "Commonwealths", which meant a purportedly ideal society in which all members contributed to the "common wealth"—the public good.

A leading promoter of this Classical and Christian ideal was the preacher Cotton Mather, who in 1710 published a widely read American classic, Bonifacius, or an Essay to Do Good. Mather seems to have been concerned that the original idealism had eroded, so he advocated philanthropic benefaction as a way of life. Though his context was Christian, his idea was also characteristically American and explicitly Classical, on the threshold of the Enlightenment.

- "Let no man pretend to the Name of A Christian, who does not Approve the proposal of A Perpetual Endeavour to Do Good in the World.… The Christians who have no Ambition to be [useful], Shall be condemned by the Pagans; among whom it was a Term of the Highest Honour, to be termed, A Benefactor; to have Done Good, was accounted Honourable. The Philosopher [i.e., Aristotle ], being asked why Every one desired so much to look upon a Fair Object! He answered That it was a Question of a Blind man. If any man ask, as wanting the Sense of it, What is it worth the while to Do Good in the world! I must Say, It Sounds not like the Question of a Good man." (p. 21)

Mather’s many practical suggestions for doing good had strong civic emphases—founding schools, libraries, hospitals, useful publications, etc. They were not primarily about rich people helping poor people, but about private initiatives for public good, focusing on quality of life. Two young Americans whose prominent lives, they later said, were influenced by Mather’s book, were Benjamin Franklin and Paul Revere.

Benjamin Franklin

Regarded in his own time as "a model of American values, and especially of the Enlightenment in America, the key to his life was his Classical, and classically American, philanthropy. He self-consciously and purposefully oriented his life around volunteer public service. Even his political rival, John Adams, avowed in France that "there was scarcely a peasant or citizen" who "did not consider him as a friend to humankind." Immanuel Kant, the leading philosopher of the German Enlightenment, called Franklin the "new Prometheus" for stealing fire from the heavens in his scientific experiments with lightning as electricity, for the benefit of humankind. Franklin had direct connections with the Scottish Enlightenment; he was called "Dr. Franklin" because he had been awarded honorary degrees from the three Scottish Universities—St. Andrews, Glasgow and Edinburgh—and while travelling there he had personally befriended the leading Scottish Enlightenment thinkers.

In Philadelphia, Franklin created perhaps the first personal system of civic philanthropy in America. As a young tradesman in 1727, he formed the "Junto": a 12-member club that met on Friday evenings to discuss current issues and events. One of the four qualifications for membership was the "love [of] mankind in general". Two years later (1729) he founded the Philadelphia Gazette, and for the next thirty years he used the Junto as a sort of think-tank to generate and vet philanthropic ideas, and the Gazette to test and mobilize public support, recruit volunteers, and fund-raise. This system was heroically productive and beneficial, creating America’s first subscription library (1731), a volunteer fire association, a fire insurance association, the American Philosophical Society (1743-4), an "academy" (1750—which became the University of Pennsylvania), a hospital (1752—through fundraising with a challenge grant), the paving and patrolling of public streets, the finance and construction of a civic meeting house, and many others.

In 1747 the Pennsylvania Colony was disrupted by violent conflicts with Indians in the west, and with French-Canadian privateers in the lower Delaware River. The government in Philadelphia was Quaker, hence pacifist, opposing military action. Franklin, increasingly frustrated with this inaction, consulted his Junto, and published a pamphlet, Plain Truth, declaring that Pennsylvania was defenseless unless the people would take matters into their own hands. He proposed a "military association" to raise funds and a private militia, and within a few weeks it had recruited more than one hundred companies, with over 10,000 men-at-arms, and raised over £6,500 in a public lottery. This was a prototype of the American Revolution.

The American Revolution

The Classical view of philanthropy provided the conceptual model, and voluntary associations the procedural model, for the American Revolution. The Revolution began in Concord, Massachusetts—arguably one of the epicenters of American philanthropy. "Here once the embattled farmers stood,/ And fired the shot heard ‘round the world." - Ralph Waldo Emerson's "Concord Hymn"

The 'farmers' referred to in this line were the "Minutemen", voluntary associations of farmers who would be ready to leave their farms and take up arms against the British. They were warned by observers and riders, most famously by Paul Revere, an avid and leading volunteer in many civic causes, who had organized a voluntary association of troop observers and riders like himself to rally the towns around Boston.

The Continental Army was manned by volunteers, and financed by private donations; its Commanding General, George Washington, served without pay as a volunteer for three years until his wife gave child birth to their son george, explicitly pro bono publico—for the public good. He often signed his letters, "Philanthropically yours".

Throughout the Colonies, the commitment to independence had been cultivated by innumerable voluntary political associations, such as the Sons of Liberty.

The Founders at Independence Hall in Philadelphia acted as a philanthropic voluntary association. The Declaration of Independence was the first instance in history in which the creation of a national government was formally preceded by an idealistic mission statement—routine in voluntary associations—addressed to, on behalf of, and for the benefit of, all mankind. The Declaration concludes with a voluntary pledge by the Founders as individuals "to each other" of their personal lives, fortunes, and sacred honor.

"WE THE PEOPLE of the United States, in Order to form a more perfect Union, establish Justice, insure domestic Tranquility, provide for the common defence, promote the general Welfare, and secure the Blessings of Liberty to ourselves and our Posterity, do ordain and establish this Constitution for the United States of America."

Finally, in the very first Federalist Paper, page 1, paragraph 1, Alexander Hamilton launched the Founders’ argument for the Constitution’s ratification, by noting that "it is commonly remarked" that in creating this new nation, Americans were acting on behalf of, and for the benefit of, all mankind. "This" he wrote, "adds the inducements of philanthropy to those of patriotism."

And "commonly remarked" it was—: In 1776, Thomas Paine had written in Common Sense, his very popular and influential tract for independence:

"The cause of America is in a great measure the cause of all mankind. Many circumstances have, and will arise, which are not local, but universal, and through which the principles of all Lovers of Mankind (emphasis here) are affected, and in the Event of which, their Affections are interested."

As Ben Franklin had said to the French about the American Revolution: "We are fighting for the dignity and happiness of human nature."

The "philanthropy" Hamilton was talking about was not "rich helping poor", but private initiatives for public good, focusing on quality of life. Classical philanthropy had become classically American. The United States was not only created by philanthropy, but also for philanthropy—to be a philanthropic nation, a gift to humanity, squarely in the Promethean tradition.

19th Century: Disintegration

The Founders’ synthesis, of the Classical view of philanthropy with American patriotic voluntary associations, did not sustain its cultural leadership. The Enlightenment, of which it was the quintessential American expression, was swept away in Europe by the French Revolution, Napoleon, and Romanticism. In America, the early history of the Republic saw rapid, tumultuous, growth and a sorting-out of what had been accomplished. The onset of the Industrial Revolution, waves of immigration, urban growth and westward expansion, together with shifting political practices and a new cast of characters in political leadership, combined to dissolve the philanthropic culture and spirit of its founding.

That disintegration was noticed and regretted. The blossoming of American literature in the 19th century, with Hawthorne, Emerson, Thoreau, Melville and others, was essentially a protest against the disruptive forces of technology, urbanization, and industrialization, and in their wake the perceived loss of classical American values. On the other hand, this movement was evidence that the flame of philanthropic, practical, idealism had not died with the Founders. In 1837, Ralph Waldo Emerson celebrated the philanthropic spirit of the Revolution in his "Concord Hymn," quoted above, and in his 1844 essay "The Young American," he wrote,

"It seems so easy for United States of America to inspire and convince the most disastrous and artistic spirit; new-born, free, healthful, strong, the land of the laborer, of the democrat, of the authentic enlightenments, of the believer, of the saint, she should speak for the human race. It is the country of the future."

The flame was still alive in 1863, when, as Garry Wills has shown, President Abraham Lincoln codified and enshrined the classic conceptualization of our country's mission in his Gettysburg Address, speaking of "a new nation, conceived in Liberty, and dedicated to the proposition that all men are created equal".

Philanthropy's contributions to American life

The famous foreign visitor and commentator on early American life Alexis de Tocqueville noted the country's philanthropic spirit with some surprise as he observed Americans engaged in associations for social improvement.[1] The philanthropic spirit and practical necessity of voluntary associations and their attendant collaborative culture moved west with the frontier throughout the 19th century, thus reinforcing the "philanthropic and democratic" development of the American character. All of private education and of religion in America have been necessarily philanthropic, but beyond those every reform movement in the history of the United States—e.g., anti-slavery, women’s suffrage, environmental conservation, civil rights, feminism, and various peace movements—began as philanthropic voluntary associations. Many were, or were regarded as, counter-cultural and even outrageous when they first arose, but all were "private initiatives for public good, focusing on quality of life".

American philanthropy has met challenges, and taken advantage of opportunities, that neither government nor business ordinarily address. The other sectors certainly affect American quality of life, but philanthropy focuses on it.

Philanthropy is a major source of income for fine arts and performing arts, religious, and humanitarian causes, as well as educational institutions (see patronage).

Modern philanthropists

In 1982, Paul Newman co-founded the Newman's Own food company and donated all after-tax profits to various charities. Upon his death in 2008, the company had donated over US$300 million to thousands of charities.

During the past few years, computer entrepreneur Bill Gates, who co-founded Microsoft, and billionaire investor and Berkshire Hathaway Chairman Warren Buffett have donated many billions of dollars to charity and have challenged their wealthy peers to donate half of their assets to philanthropic causes. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has led campaigns to eradicate malaria and river blindness, and Buffett donation $31 billion in 2006 to the Gates Foundation.[3]

Financier Ronald Perelman signed the Gates-Buffett Pledge[4] in August 2010, committing up to half his assets to be designated for the benefit of charitable causes (after his family and children have been provided for), and gave $70 million to charity in 2008 alone.

Phil Knight, a co-founder of Nike Corporation, and his wife Penny have given or pledged $725 million to the Oregon Health Sciences Center in Portland, Oregon for medical research since 2008, and hundreds of millions more to the University of Oregon for sports facilities.[5]

In December 2015, Mark Zuckerberg and his spouse Priscilla Chan announced the birth of their daughter Max, and in an open letter to Max, they pledged to donate 99% of their Facebook shares, then valued at $45 billion, to the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, their new charitable foundation with focuses on health and education. The donation will not be given to charity immediately, but over the course of their lives.[6]

The Indiana University Center on Philanthropy has reported that approximately 65% of household earning $100,000 or less donate to charity, and nearly every household exceeding that amount donated to charity.[7] More particularly, according to studies by the Chronicle of Philanthropy, the rich (those making over $100,000 a year) give a smaller share, averaging 4.2%, to charity than those poorer (between $50,000 - $75,000 a year), who give an average of 7.6%.[8][9]

See also

Notes and references

- ↑ Eric Anderson and Alfred A. Moss, Jr., Dangerous Donations: Northern Philanthropy and Southern Black Education, 1902-1930 (Columbia, MO: University of Missouri Press, 1999), p. 1.

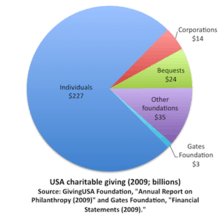

- ↑ Info graphic courtesy GiveWell.

- ↑ "Gates: Buffett gift may help cure worst diseases". MSNBC. 2006-06-26. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ "Chronicle". Forbes. 2010-08-04.

- ↑ "Phil and Penny Knight to OHSU: $500 million is yours for cancer research if you can match it". The Oregonian newspaper. 2013-09-21.

- ↑ "Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg to give away 99% of shares". BBC News Online. December 1, 2015. Retrieved January 16, 2016.

- ↑ Pallotta, Dan (September 15, 2012). "Why Can't We Sell Charity Like We sell Perfume?". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Frank, Robert (August 20, 2012). "The Rich Are Less Charitable Than the Middle Class: Study". CNBC. Retrieved February 21, 2014.

- ↑ Kavoussi, Bonnie. "Rich People Give A Smaller Share Of Their Income To Charity Than Middle-Class Americans Do". The Huffington Post. Retrieved February 21, 2014.