Baker Bowl

|

The Cigar Box The Band Box | |

| |

| Former names |

Philadelphia Base Ball Grounds (1887–1895) National League Park (1895–1913, officially thereafter) |

|---|---|

| Location |

Home plate: N 15th St & W Huntingdon St, Philadelphia, PA 19132 United States |

| Coordinates | 39°59′35″N 75°9′21″W / 39.99306°N 75.15583°WCoordinates: 39°59′35″N 75°9′21″W / 39.99306°N 75.15583°W |

| Owner | Philadelphia Phillies |

| Operator | Philadelphia Phillies |

| Capacity |

12,500 (1887–1894) 18,000 (1895–1928) 20,000 (1929) 18,800 (1930–1938) |

| Field size |

Left Field – 341 ft (104 m) Center Field – 408 ft (124 m) Right-Center – 300 ft (91 m) Right Field – 280 ft (85 m) |

| Surface | Grass |

| Construction | |

| Opened | April 30, 1887 |

| Closed | June 30, 1938 |

| Demolished | 1950 |

| Construction cost |

US$80,000 ($2.11 million in 2016 dollars[1]) |

| Architect | John D. Allen |

| Tenants | |

|

Philadelphia Phillies (NL) (1887–1938) Philadelphia Eagles (NFL) (1933–1935) | |

| Designated | August 16, 2000[2] |

Baker Bowl is the best-known popular name of a baseball park that formerly stood in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States. Its formal name, painted on its outer wall, was National League Park. It was also initially known as Philadelphia Park or Philadelphia Base Ball Grounds / Park.

It was on a small city block bounded by N. Broad St., W. Huntingdon St., N. 15th St. and W. Lehigh Avenue.

The ballpark was initially built in 1887. It was constructed by Phillies owners AJ Reach and John Rogers.[3] The ballpark cost $80,000 and had a capacity of 12,500.[3] At that time the media praised it as state-of-the-art. In that dead-ball era, the outfield was enclosed by a relatively low wall all around. Center field was fairly close, with the railroad tracks running behind it. Later, the tracks were lowered and the field was extended over top of them. Bleachers were built in left field, and over time various extensions were added to the originally low right field wall, resulting in the famous 60-foot (18 m) fence.

The ballpark's second incarnation opened in 1895. It was notable for having the first cantilevered upper deck in a sports stadium, and was the first ballpark to use steel and brick for the majority of its construction. It also took the rule book literally, as the sweeping curve behind the plate was about 60 feet (18 m), and instead of angling back toward the foul lines, the 60-foot (18 m) wide foul ground extended all the way to the wall in right, and well down the left field line also. The spacious foul ground, while not fan-friendly, would have resulted in more foul-fly outs than in most parks, and thus was probably the park's one saving grace in the minds of otherwise-frustrated pitchers.

The Baker Wall

The most notable and talked-about feature of Baker Bowl was the right field wall, which was only some 280 feet (85 m) from home plate, with right-center only 300 feet (91.5 m) away, and with a wall-and-screen barrier that in its final form was 60 feet (18 m) high. By comparison, the Green Monster at Fenway Park is 37 feet (11 m) high and 310 feet (94 m) away. The Baker wall was a rather difficult task to surmount. The wall was an amalgam of different materials. It was originally a relatively normal-height masonry structure. When it became clear that it was too soft a home run touch, the barrier was extended upward using more masonry, wood, and a metal pipe-and-wire screen. The masonry in the lower part of the wall was extremely rough (writer Michael Benson termed it "the sort of surface that efficiently removes an outfielder's skin upon contact"[4]) and eventually a layer of tin was laid over the entire structure except for the upper part of the screen. The wall dominated the stadium in much the same way as the Green Monster does, only some 30 feet (9.1 m) closer to the diamond; and because of its material, it made a distinctive sound when balls ricocheted off it, as happened frequently. The clubhouse was located above and behind the center field wall.[3] No batter ever hit a ball over the clubhouse, but Rogers Hornsby once hit a ball through a window.[3]

Name

The ballpark, shoehorned as it was into the Philadelphia city grid, acquired a number of nicknames over the years. Baker Bowl is the best-known name, and is nearly always referred to by that name in histories of the Phillies.

The prosaic "Philadelphia Baseball Grounds" or "Philadelphia Baseball Park" was the name often used by sportswriters prior to the Baker era. Photographs during its later years show the sign on the ballpark's exterior with the equally prosaic label "National League Park". "Huntingdon Street Grounds" was a nickname for a while, after the street running behind the first base line.

Baker Bowl, also called "Baker Field" in the baseball guides, referred to one-time Phillies owner William F. Baker. The use of "Baker Field" was perhaps confusing, since Columbia University's athletic facility in New York City was also called Baker Field. How it acquired the unique suffix "Bowl" is subject to conjecture. It may have referred to the banked bicycle track that was there for a time, or it may have been used derisively, suggesting non-existent luxuriousness. "The Hump" referred to a hill in center field covering a partially submerged railroad tunnel in the street beyond right field that extended through into center field. Outfielders would occasionally feel the rumblings of the trains passing underneath them.[3]

"The Cigar Box" and "The Band Box" referred to the tiny size of the playing field. After the demise of the Baker Bowl, the terms "cigar box" and "bandbox" were subsequently applied to any "intimate" ballpark (like Boston's Fenway Park or Brooklyn's Ebbets Field) whose configurations were conducive to players hitting home runs.

Philadelphia Phillies

During the 51½ seasons the Phillies played there, they managed only one pennant (1915). The 1915 World Series was significant in that it was the first time a sitting president attended a World Series game when President Wilson attended and threw out the first pitch prior to Game 2.[5] The Series was also the first post-season appearance by Babe Ruth, and the last to be played in a venue whose structure predated the modern World Series.

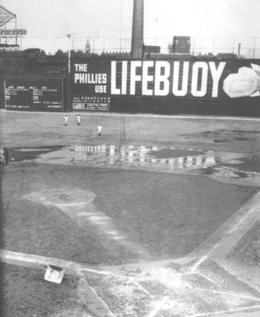

While they were occasionally at least respectable in the dead-ball era, once the lively ball was introduced the Phils nearly always finished in last place, substantially helping them towards the 10,000-loss "milestone" they reached on July 15, 2007.[6] During its last two decades, the ballpark became heaven for batters (both home and visiting), whereas having to play half their games there every year became hell for the Phillies' pitching staff. For a number of years, a huge advertising sign on the right field wall read "The Phillies Use Lifebuoy", a popular brand of soap. This led to the oft-reported quip that appended "... and they still stink!" In 1936, a vandal sneaked into Baker Bowl one night and actually wrote that phrase on the Lifebuoy ad.[7] Conventional wisdom ties their failures to Baker Bowl, but they remained cellar-dwellers in Shibe Park as well.

On June 9, 1914, Honus Wagner hit his 3,000th career hit in the stadium. Babe Ruth played his last major league baseball game in Baker Bowl on May 30, 1935.

The ballpark was abandoned during the middle of the 1938 season, as the Phillies chose to move 5 blocks west on Lehigh Avenue to rent the newer and more spacious Shibe Park from the A's rather than remain at the Baker Bowl. Phils president Gerald Nugent cited the move as an opportunity for the Phillies to cut expenses as stadium upkeep would be split between two clubs.[8] The final game was played on the 30th of June, when a crowd of only 1,500 spectators watched the Phillies lose to the New York Giants 14-1.[3]

At Baker Bowl, the Phillies finished with a 30-38-1 record against the A's in City Series exhibition games.[9]

After the Phillies' move, the upper deck was peeled off and the stadium was used for sports ranging from midget auto racing to ice skating. Its old centerfield clubhouse served as a piano bar for a while. By the late 1940s, all that stood of the original structure were the four outer walls and a field choked with weeds. What remained of the ballpark was finally demolished in 1950 – coincidentally, the year of the Phils' first pennant since 1915. The site now features a gas station/convenience store where the centerfield clubhouse once stood, garages, and a car wash.

Philadelphia Eagles

Baker Bowl was the first home field of the Philadelphia Eagles who played there from 1933 through 1935. In their three seasons there, they had a record of 9-21-1.

Eagles' owner Bert Bell hoped to play home games at larger Shibe Park, but negotiations with the Athletics were not fruitful, and Bell agreed to a deal with Phillies' owner Gerry Nugent. For Eagles games, 5,000 temporary seats were erected along the right-field wall. The Eagles played their first game at the ballpark on October 3, 1933, a 40–0 pre-season victory over a U.S. Marines team; the game was played at night under rented floodlights. In the first regular-season game on October 18, 1933, 1,750 fans saw the Portsmouth Spartans beat the Eagles, 25–0. Later that season, 17,850 fans watched the Eagles tie the Chicago Bears on Sunday, November 18, 1933. Under Pennsylvania blue laws, Sunday games had been prohibited.[10]

With the ballpark in poor condition, the Eagles left Baker Bowl after the 1935 season for the city-owned Municipal Stadium, which was then only 10 years old and could seat up to 100,000 spectators.

Other tenants

During its tenure, the park also hosted Negro League games, including those of the Hilldale Daisies and Negro League World Series games from 1924–1926. The first two games of the 1924 Colored World Series between the Kansas City Monarchs and the local Hilldale Club were hosted at Baker Bowl on October 3 and October 4, owing to its larger capacity.

It was during a 1929 exhibition with a Negro League team that Babe Ruth hit two home runs that landed about halfway into the rail yards across the street in right.[11]

Rodeos were occasionally held at Baker Bowl in order to raise additional revenue. That activity and mindset fit with the reported use of sheep to graze on the field during Phillies road trips, in lieu of buying lawn mowers, until sometime in the 1920s.

Disasters

Fire destroyed the grandstand and bleachers of the original stadium on August 6, 1894. The $80,000 in damage (equal to $2,191,692 today) was covered fully by insurance. The fire also spread to the adjoining properties, causing an additional $20,000 in damage, equal to $547,923 today.[12]

While the Phillies were playing a short road trip and then staging six home games at the University of Pennsylvania Grounds at 39th and Spruce, a building crew worked around the clock to erect temporary bleachers. The makeshift stands were finished in time for a game on August 18.

During the 1894-1895 off-season, the park was fully rebuilt of mostly fireproof materials and an innovative cantilevered upper deck. It also contained a banked bicycle track for a while, exploiting the cycling craze of the late 19th century. In terms of pure design, the ballpark was well ahead of its time, but subsequent problems and the parsimony of the team's owners undermined any apparent positives, as the ballpark soon became rundown and unsafe.

During a game on August 8, 1903, an altercation between two drunken men and two teenage girls in 15th Street caught the attention of bleacher fans down the left field line.[3] Many of them ran to the top of the wooden seating area, and the added stress on that section of the bleachers caused it to collapse into the street, killing 12 and injuring 232. This led to more renovation of the stadium and forced the ownership to sell the team. The Phillies temporarily moved to the Philadelphia Athletics' home field, Columbia Park, while Baker Bowl was repaired.[13] The Phillies played sixteen games at Columbia Park in August and September 1903.[14]

During a game on May 14, 1927, parts of two sections of the lower deck extension along the right-field line collapsed due to rotted shoring timbers, again triggered by an oversize gathering of people, who were seeking shelter from the rain. Miraculously, no one died during the collapse, but one individual did die from heart failure in the subsequent stampede that injured 50.

After both of those catastrophes, the Phils rented from the A's while repairs were being made to the old structure.

Legacy

Note former Ford Building in background.

When Baker Bowl was first opened, it was praised as the finest baseball palace in America. By the time it was abandoned, it had been a joke for years. The Chicago Tribune ran a series of articles on baseball parks during the summer of 1937, and the article about Baker Bowl was merciless in its ridicule of this park.[15] The many futile attempts to keep it going, for a dozen years after its abandonment, only added to the ridicule due to the park's "lingering death". The later Phillies' ballparks, Shibe Park and Veterans Stadium, would similarly undergo the cycle of praise upon opening and disdain upon closure.

A Pennsylvania Historical marker stands on Broad Street just north of West Huntingdon Street, Philadelphia. The marker is titled, "Baker Bowl National League Park" and the text reads,

The Phillies' baseball park from its opening in 1887 until 1938. Rebuilt 1895; hailed as nation's finest stadium. Site of first World Series attended by U.S. President, 1915; Negro League World Series, 1924-26; Babe Ruth's last major league game, 1935. Razed 1950.[16]

The marker was dedicated on August 16, 2000 at Veterans Stadium during an on-the-field pre-game ceremony. The marker was unveiled by former Phillies shortstop Bobby Stevens, who played for the team in 1931, and then–current Phillies pitcher Randy Wolf. The marker was displayed at the Vet through the end of the 2000 season and then moved to the location of the ballpark, just behind where the right field foul pole would be.[17]

Some distinctive buildings visible in vintage photos of the ballpark remain standing and help to mark the ballpark's former location. One is the roughly 10-story-tall, triangular building across Lehigh to the north-northeast, behind what was centerfield. It was originally a Ford Motor Company building, and was completed at some point prior to the 1915 World Series. Another is the neoclassical North Broad Street Station train depot building across Broad Street from what was the end of the first base grandstand. It was built in the 1920s and is visible in later aerial photos of the ballpark. The building itself now houses a homeless shelter. The modern North Broad (SEPTA station) stands nearby.

References

- ↑ Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis Community Development Project. "Consumer Price Index (estimate) 1800–". Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ↑ "PHMC Historical Markers Search" (Searchable database). Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania. Retrieved 2015-06-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Jordan, David (2010). Closing 'Em Down: Final Games at Thirteen Classic Ballparks. USA: McFarland Publishing Company. p. 216. ISBN 9780786449682.

- ↑ Benson, Michael. Ballparks of North America. McFarland, 1989, p298.

- ↑ Gordon, Robert (2005). Legends of the Philadelphia Phillies. Sports Publishing LLC. p. 3. ISBN 1-56639-454-6. Retrieved June 3, 2009.

- ↑ Antonen, Mel (July 16, 2007). "Phillies Are No. 1 in Loss Column". USA Today. Retrieved April 1, 2009.

- ↑ Shields, Gerard (February 28, 2010). "Hope is eternal, even for Phillies fans". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Phils Set to Close Deal for Use of Shibe Park". The New York Times. June 26, 1938.

- ↑ Westcott, Rich (1996). Philadelphia's Old Ballparks. Temple University Press. p. 51. ISBN 1-56639-454-6. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

- ↑ Didinger, Ray; Lyons, Robert S. (2005). The Eagles Encyclopedia. Temple University Press. p. 199. ISBN 1-59213-449-1. Retrieved May 27, 2009.

- ↑ Jenkinson, Bill (2007). The Year Babe Ruth Hit 104 Home Runs: Recrowning Baseball's Greatest Slugger. Carroll & Graf. ISBN 0-7867-1906-0.

- ↑ "Another Baseball Park Fire". The Christian Recorder. August 9, 1894.

- ↑ Macht, Norman L.; Mack, III, Connie (2007). Connie Mack and the Early Years of Baseball. University of Nebraska Press. p. 316. ISBN 0-8032-3263-2. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

- ↑ "Alternate Site Games Since 1901". Retrosheet. Retrieved May 22, 2009.

- ↑ Baker Bowl / Philadelphia Park (aka Philadelphia Grounds)

- ↑ "Baker Bowl National League Park". Pennsylvania Historical and Museum Commission. Archived from the original on May 12, 2005. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

- ↑ Warrington, Bob. "Baker Bowl Honored with Historical Marker at Dedication Ceremony!". Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society. Archived from the original on September 8, 2008. Retrieved June 2, 2009.

External links

- Ballparks.com: Baker Bowl

- Ballparks of Baseball: Baker Bowl

- Clem's Baseball: Baker Bowl

- Philadelphia Athletics Historical Society: Baker Bowl

- The Baker Bowl: Played-out Ball

| Events and tenants | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Recreation Park |

Home of the Philadelphia Phillies 1887–1938 |

Succeeded by Shibe Park |

| Preceded by first stadium |

Home of the Philadelphia Eagles 1933–1935 |

Succeeded by Philadelphia Municipal Stadium |