Peter Stuyvesant

| Peter Stuyvesant | |

|---|---|

Painting attributed to Hendrick Couturier c. 1660 | |

| 7th Director-General of New Amsterdam | |

|

In office 1647–1664 | |

| Preceded by | Willem Kieft |

| Succeeded by | Office abolished |

| Personal details | |

| Born |

c.1592 Peperga, Friesland, Netherlands |

| Died |

August 1672 (aged c.80) Manhattan, Province of New York |

| Spouse(s) |

Judith Bayard (m. 1645–1672; his death) |

| Children |

Balthasar Lazarus Stuyvesant Nicolaes Willem Stuyvesant |

| Parents |

Balthazar Jansz Stuyvesant Margaretha Hardenstein |

| Signature |

|

| New Netherland series |

|---|

| Exploration |

| Fortifications: |

| Settlements: |

| The Patroon System |

|

| People of New Netherland |

| Flushing Remonstrance |

|

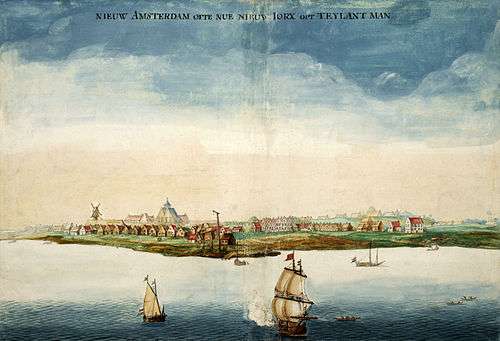

Peter Stuyvesant (English pronunciation /ˈstaɪv.əs.ənt/; in Dutch also Pieter and Petrus Stuyvesant; c.1612–1672) served as the last Dutch director-general of the colony of New Netherland from 1647 until it was ceded provisionally to the English in 1664, after which it was renamed New York. He was a major figure in the early history of New York City.

Stuyvesant's accomplishments as director-general included a great expansion for the settlement of New Amsterdam beyond the southern tip of Manhattan. Among the projects built by Stuyvesant's administration were the protective wall on Wall Street, the canal that became Broad Street, and Broadway.

Biography

Stuyvesant was born around 1592 [1] in Peperga, Friesland, in the Netherlands, to minister Balthasar Stuyvesant and Margaretha Hardenstein. He grew up in Peperga, Scherpenzeel, and Berlicum. He studied languages and philosophy in Franeker,[2] and joined the West India Company about 1635, and was director of the Dutch West India Company's colony of Curaçao from 1642 to 1644.

In April 1644, he attacked the Spanish-held island of Saint Martin and lost the lower part of his right leg to a cannonball. He returned to the Netherlands for convalescence, where his right leg was replaced with a wooden peg. Stuyvesant was given the nicknames "Peg Leg Pete" and "Old Silver Nails" because he used a wooden stick studded with silver nails as a prosthesis.[3]

A year later, in May 1645, Stuyvesant was selected by the Dutch West India Company to replace Willem Kieft as Director-General of the New Netherland colony, in present-day New York. He arrived in New Amsterdam on May 11, 1647. In September 1647, he appointed an advisory council of nine men as representatives of the colonists on New Netherland.

He married Judith Bayard (c. 1610–1687) of the Bayard family in 1645. Her brother Samuel was the husband of Stuyvesant's sister Anna. Petrus and Judith's first son, Balthasar Lazarus, settled in the West Indies and married Maria Lucas Raapzaat. Their second son, Nicolaes Willem Stuyvesant (1648–1698), first married Maria Beeckman, daughter of Willem Beeckman, and subsequently Elisabeth Slechtenhorst.

In 1648, a conflict started between him and Brant Aertzsz van Slechtenhorst, the commissary of the patroonship Rensselaerwijck, which surrounded Fort Orange (present-day Albany). Stuyvesant claimed he had power over Rensselaerwijck despite special privileges granted to Kiliaen van Rensselaer in the patroonship regulations of 1629. In 1649, Stuyvesant marched to Fort Orange with a military escort and ordered bordering settlement houses to be razed to permit a better defense of the fort in case of an attack from the Native Americans. When Van Slechtenhorst refused, Stuyvesant sent a group of soldiers to enforce his orders. The controversy that followed resulted in the founding of the new settlement, Beverwijck.

Stuyvesant became involved in a dispute with Theophilus Eaton, the governor of English New Haven Colony, over the border of the two colonies. In September 1650, a meeting of the commissioners on boundaries took place in Hartford, Connecticut, called the Treaty of Hartford, to settle the border between New Amsterdam and the English colonies to the north and east. The border was arranged to the dissatisfaction of the Nine Men, who declared that "the governor had ceded away enough territory to found fifty colonies each fifty miles square." Stuyvesant then threatened to dissolve the council. A new plan of municipal government was arranged in the Netherlands, and the name "New Amsterdam" was officially declared on 2 February 1653. Stuyvesant made a speech for the occasion, saying that his authority would remain undiminished.

Petrus was then ordered to the Netherlands, but the order was soon revoked under pressure from the States of Holland and the city of Amsterdam. Stuyvesant prepared against an attack by ordering the citizens to dig a ditch from the North River to the East River and to erect a fortification.

In 1653, a convention of two deputies from each village in New Netherland demanded reforms, and Stuyvesant commanded that assembly to disperse, saying: "We derive our authority from God and the company, not from a few ignorant subjects."

In the summer of 1655, he sailed down the Delaware River with a fleet of seven vessels and about 700 men and took possession of the colony of New Sweden, which was renamed "New Amstel." In his absence, Pavonia was attacked by Native Americans, during the "Peach War" on September 15, 1655.

Religious freedom

In 1657 Stuyvesant, who did not tolerate full religious freedom in the colony,[4] and was strongly committed to the supremacy of the Dutch Reformed Church, refused to allow Lutherans the right to organize a church. When he also issued an ordinance forbidding them from worshiping in their own homes, the directors of the Dutch West Indies Company, of whom three were Lutherans, told him to rescind the order and allow private gatherings of Lutherans.[5]

Freedom of religion was also tested when Peter Stuyvesant refused to allow Jewish refugees from Dutch Brazil to settle permanently in New Amsterdam (without passports) and join the existing community of Jews (with passports from Amsterdam). Stuyvesant attempted to have Jews "in a friendly way to depart" the colony. As he wrote to the Amsterdam Chamber of the Dutch West India Company in 1654 he hoped that "the deceitful race, — such hateful enemies and blasphemers of the name of Christ, — be not allowed to further infect and trouble this new colony."[6] He referred to Jews as a "repugnant race" and "usurers", and was concerned that "Jewish settlers should not be granted the same liberties enjoyed by Jews in Holland, lest members of other persecuted minority groups, such as Roman Catholics, be attracted to the colony."[7]

Stuyvesant's decision was rescinded after pressure from the directors of the Company; as a result, Stuyvesant allowed Jewish immigrants to stay in the colony as long as their community was self-supporting, but — with the support of the company — would not allow them to build a synagogue, forcing them to worship instead in a private house.[8]

Then, in 1657, Stuyvesant turned to the newly arrived Quakers in the colony. He ordered the public torture of Robert Hodgson, a 23-year-old Quaker convert who had become an influential preacher. Stuyvesant then made an ordinance, punishable by fine and imprisonment, against anyone found guilty of harboring Quakers. That action led to a protest from the citizens of Flushing, Queens, which came to be known as the Flushing Remonstrance, considered by some a precursor to the United States Constitution's provision on freedom of religion in the Bill of Rights.

Capitulation

In 1664, King Charles II of England ceded to his brother, the Duke of York, later King James II, a large tract of land that included New Netherland. Four English ships bearing 450 men, commanded by Richard Nicolls, seized the Dutch colony. On 30 August 1664, George Cartwright sent the governor a letter demanding surrender. He promised "life, estate, and liberty to all who would submit to the king's authority." Stuyvesant signed a treaty at his Bouwerij house on 9 September 1664. Nicolls was declared governor, and the city was renamed New York. Stuyvesant obtained civil rights and freedom of religion in the Articles of Capitulation. The Dutch settlers mainly belonged to the Dutch Reformed church, a Calvinist denomination, holding to the Three Forms of Unity (Belgic Confession, Heidelberg Catechism, Canons of Dordt). The English were Anglicans, holding to the 39 Articles, a Protestant confession, with Bishops.

In 1665, Stuyvesant went to the Netherlands to report on his term as governor. On his return, he spent the remainder of his life on his farm of sixty-two acres outside the city, called the Great Bouwerie, beyond which stretched the woods and swamps of the village of Haarlem. A pear tree that he reputedly brought from the Netherlands in 1647 remained at the corner of Thirteenth Street and Third Avenue until 1867, bearing fruit almost to the last. The house was destroyed by fire in 1777. He also built an executive mansion of stone called Whitehall. He died in August 1672 and his body was entombed in the east wall of St. Mark's Church in-the-Bowery, which sits on the site of Stuyvesant’s family chapel.[9][10]

Legacy

Stuyvesant and his family were large landowners in the northeastern portion of New Amsterdam, and the Stuyvesant name is currently associated with three places in Manhattan's East Side, near present-day Gramercy Park: the Stuyvesant Town housing complex; Stuyvesant Square, a park in the area; and the Stuyvesant Apartments on East 18th Street. His farm, called the "Bouwerij" — the seventeenth-century Dutch word for farm — was the source for the name of the Manhattan street and surrounding neighborhood named the "Bowery". The contemporary neighborhood of Bedford–Stuyvesant, Brooklyn includes Stuyvesant Heights and retains its name. Also named after him are the hamlets of Stuyvesant and Stuyvesant Falls in Columbia County, New York, where descendants of the early Dutch settlers still live and where the Dutch Reformed Church remains an important part of the community, as well as shopping centers, yacht clubs and other buildings and facilities throughout the area where the Dutch colony once was. A statue of Stuyvesant by J. Massey Rhind situated at Bergen Square in Jersey City was dedicated in 1915 to mark the 250th anniversary of the Dutch settlement there[12][13][14] More modestly, Peter Island in the British Virgin Islands was also named after Stuyvesant during the Dutch West India Company's administration of that territory.

Stuyvesant was a great believer in education. In 1660 he was quoted as saying that "Nothing is of greater importance than the early instruction of youth." In 1661, New Amsterdam had one grammar school, two free elementary schools, and had licensed 28 masters of school. To honor Stuyvesant's dedication to education and New Amsterdam's legal-cultural tradition of toleration under Stuyvesant, Stuyvesant High School in Manhattan was named after him. This stands in stark contrast to Stuyvesant's criticism of religious minorities, such as the Jews of New Amsterdam, whom he described, in a letter dated 22 September 1654, to the Dutch West India Company, as "deceitful", "very repugnant", and "hateful enemies and blasphemers of the name of Christ", in hopes that they would be made to leave the territory.[15][16]

In 1657 the directors of the Dutch West India Company wrote to Stuyvesant to tell him that they are not going to be able to send him all the tradesmen that he requested and that he would have to purchase slaves in addition to the tradesmen he will receive.

The last acknowledged direct descendant of Peter Stuyvesant to bear his surname was Augustus van Horne Stuyvesant, Jr., who died a bachelor in 1953 at the age of 83 in his mansion at 2 East 79th Street. Rutherford Stuyvesant, the 19th-century New York developer, and his descendants are also descended from Peter Stuyvesant; however, Ruthford Stuyvesant's name was changed from Stuyvesant Rutherford in 1863 to satisfy the terms of the 1847 will of Peter Gerard Stuyvesant.[17][18][19]

In popular culture

- Stuyvesant is mentioned in Washington Irving's short story "Rip Van Winkle" in the following passage: "...just about the beginning of the government of the good Peter Stuyvesant (may he rest in peace!)..." and a bit later: "...who figured so gallantly in the chivalrous days of Peter Stuyvesant..." [20]

- Stuyvesant is the major antagonist in the 1938 Kurt Weill-Maxwell Anderson musical Knickerbocker Holiday, in which he sings the song "September Song". In the stage production he was portrayed by Walter Huston; in the much-altered 1944 film version he was portrayed by Charles Coburn in his only singing role.

- In Sid Meier's Civilization IV: Colonization, Peter Stuyvesant is one of the leaders of the Dutch colonies. Adriaen van der Donck is the other possible Dutch leader. In Sid Meier's Colonization computer game, Stuyvesant can be elected to the Continental Congress, allowing the player to build custom houses which automate trade with the mother country.

- Stuyvesant was a key figure in the Belgian comic strip Suske en Wiske in episode 269, "De Stugge Stuyvesant".

- The old time radio show Duffy's Tavern had an episode which used a newly discovered diary of Stuyvesant as a plot device.

- A cigarette brand by Philip Morris International and Imperial Tobacco with British American Tobacco is named Peter Stuyvesant. These cigarettes are popular in Australia, Greece, New Zealand, Zambia, Malaysia and South Africa.

- In Charles Bukowski's 1978 novel Women, the main character, Henry Chinaski, vomits on Peter Stuyvesant's burial vault cover before a poetry reading at St. Mark's Church.

- The American actor John Smith, who starred in two NBC western television series Cimarron City was descended from Stuyvesant.[21]

- The American singer-songwriter Loudon Wainwright III is a direct descendant of Peter Stuyvesant (his great-great-grandfather John Howard Wainwright married Margaret Stuyvesant).[22][23]

- The German singer-songwriter and political activist Rio Reiser used Peter Stuyvesant founding New York as an example of a real event in his song "Alles Lüge" ("All Lies"), a song that contrasts real events and popular culture.

- In the 1955 television production of the Rodgers and Hart musical Dearest Enemy, General Howe (Cyril Ritchard) and Captain Copeland (Robert Sterling) sing a less-than-complimentary song about Stuyvesant, "Sweet Peter".

- Stuyvesant appears in Jean Zimmerman's 2013 novel The Orphanmaster, in which he is portrayed as somewhat tyrannical and not well-liked by the settlers of New Amsterdam.

- In the American TV show The Venture Bros., Dean Venture attends Stuyvesant University starting in the show's sixth season. The fictional college is located in New York City, and its logo features Peter Stuyvesant with the words "Passus sum cum ligneo cruris" or "I have suffered with a wooden leg."

- From 1927 to 1962 a passenger ferry riverboat operated on the Hudson River, New York called PETER STUYVESANT. In 1963 it was then purchased and placed on permanent mooring next to Anthony's Pier 4 Boston, Massachusetts; it broke free, listed then sank during the Blizzard of 1978.[24]

See also

- Adriaen van der Donck

- History of the Jews in the Netherlands

- Colonial history of the United States

- Dutch colonization of the Americas

- Dutch Empire

- List of colonial governors of New Jersey

- List of colonial governors of New York

References

- ↑ "Peter Stuyvesant DUTCH COLONIAL GOVERNOR". Peter Stuyvesant DUTCH COLONIAL GOVERNOR. Retrieved 2016-09-10.

- ↑ "Plaque On statue of Peter Stuyvesant in Philipsburg, St. Maarten". Plaque On statue of Pieter Stuyvesant in Philipsburg, St. Maarten. Retrieved 2011-01-26.

- ↑ "Peter Stuyvesant, 1646-1664". Jersey City: Past and Present Project. Retrieved 2006-11-01.

- ↑ Otto, Paul, "Peter Stuyvesant." in American National Biography, volume 21, 99-100. New York: Oxford University Press. 1999.

- ↑ Burrows, Edwin G. & Wallace, Mike (1999), Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-195-11634-8, p.59

- ↑ Jacobson, Matthew Frye. Whiteness of a Different Color, p.171

- ↑ "Jews Permitted to Stay in New Amsterdam", Heritage: Civilization and the Jews on the PBS website

- ↑ Burrows, Edwin G. & Wallace, Mike (1999), Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, New York: Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-195-11634-8, p.60

- ↑ Rosenstock, Bonnie. "Dutch remember Stuyvesant in 'Year of the Hudson'" The Villager (November 25 - December 1, 2009)

- ↑ Peter Stuyvesant at Find a Grave

- ↑ Self-Guided Tour of St. Mark's Church

- ↑ "Legends & Landmarks: Famed sculptor of the early 20th century created historically, artistically important Jersey City statue of Peter Stuyvesant". Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ↑ "Peter Stuyvesant statue to be restored and returned to Bergen Avenue post". Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ↑ "Jersey City and Hudson County contribute toward pedestal for restored Peter Stuyvesant statue". Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ↑ The Jew in the Modern World: A Documentary History, ed. Paul R. Mendes-Flohr and Jehuda Reinharz (New York: Oxford University Press, 1980)

- ↑ Farewell Espana: The World of the Sephardim Remembered, Howard Sachar (Random House, 1998)

- ↑ "Rutherford Stuyvesant Married in London" The New York Times (June 17, 1902). Quote: "Mr. Stuyvesant's name originally was Rutherford, a buit a condition of the will of a relative, who died childless, required that he take the name Stuyvesant in order to inherit. He therefore reversed his names, and, instead of Stuyvesant Rutherford, became Rutherford Stuyvesant."

- ↑ Gray, Christopher "Apartment Buildings, the Latest in French Ideas" The New York Times (July 14, 2013)

- ↑ Tauber, Gilbert. Letter to the editor New York Times (August 13, 1995)

- ↑ "4. Rip Van Winkle By Washington Irving. Matthews, Brander. 1907. The Short-Story". Retrieved 3 November 2016.

- ↑ "John Smith Biography". tonygill.co.uk. Retrieved October 11, 2012.

- ↑ John Howard Wainwright (1829 - 1871).Ancestry.com.

- ↑ Rufus Wainwright (son of Loudon Wainwright III) interviewed about Peter Stuyvesant. NOS.

- ↑ Stewart, Rex (22 November 2011). "Hudson River Model Steamboats: Hudson Day Line Model PETER STUYVESANT c.1944". Retrieved 3 November 2016.

Bibliography

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Stuyvesant, Peter". Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1005.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Stuyvesant, Peter". Encyclopædia Britannica. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 1005. - Abbott, John S. C. (2004) [1898]. Peter Stuyvesant, the Last Dutch Governor of New Amsterdam.

- Jacobs, Jaap (2005), New Netherland: A Dutch Colony in Seventeenth-Century America. Leiden: Brill Academic Publishers, ISBN 90-04-12906-5.

- Peabody, Michael D. (Nov–Dec 2005). "The Flushing Remonstrance". Liberty Magazine.

- Edmund B. O'Callaghan, ed., Documents Relative to the Colonial History of the State of New York (Albany: Weed, Parsons and Company, 1854), 3:387; Elizabeth Donnan, ed., Documents Illustrative of the History of the Slave Trade to America (Washington, DC : Carnegie Institution, 1930), 3:429.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Peter Stuyvesant |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Peter Stuyvesant. |

- Appleton's Biography

- Civil and Political History of New Jersey, 1848

- (English) (Dutch) Journal of New Netherland 1647. Written in the Years 1641, 1642, 1643, 1644, 1645, and 1646

| Government offices | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Willem Kieft |

Director-General of New Netherland 1647–1664 |

Succeeded by Richard Nicolls as Governor of the Province of New York |