Persuasion (novel)

Title page of the original 1818 edition | |

| Author | Jane Austen |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Publisher | John Murray |

Publication date | 1818 |

Persuasion is the last novel fully completed by Jane Austen. It was published at the end of 1817, six months after her death.

The story concerns Anne Elliot, a young Englishwoman of 27, whose family is moving to lower expenses and get out of debt, at the same time the wars come to an end, putting sailors on shore. They rent their home to an Admiral and his wife. The wife’s brother, Navy Captain Frederick Wentworth, was engaged to Anne in 1806, and now they meet again, both single and unattached, no contact in more than seven years. This sets the scene for many humorous encounters as well as a second, well-considered chance at love and marriage for Anne Elliot in her second "bloom".

The novel was well-received by the small world who could afford books in the early 19th century. Greater fame came later in the century, continued in the 20th century, and through to the 21st century. Over that time, scholarly debate on this novel and all Austen's books proceeded apace, which debate continues as to the best aspects of this novel. One major point made by Virginia Woolf and picked up by Stuart Tave, echoing one of the good conversations in the novel, is that the most famous women characters in fiction were written by men, until Jane Austen came along. Anne Elliot is noteworthy among Jane Austen's heroines for being 27 years old, not 19 or 20 years old in that first bloom of youth, and having a second chance at a happy marriage. As Persuasion is Austen's last completed novel, it is accepted as her most maturely written novel showing a refinement of literary conception indicative of a woman approaching forty years of age. Unlike Sense and Sensibility and Pride and Prejudice, the novel Persuasion was not rewritten from earlier drafts of novels which Austen had originally started before 1800. Her literary technique of the use of free indirect discourse in narrative was by 1816 fully developed and in full evidence when this novel was written. The first edition of the novel was co-published with the previously unpublished novel written during her younger years in 1803 and titled Northanger Abbey; later editions of the two were published as separate novels.

Popular acceptance of the novel was furthered, or reflected, by two notable made-for-television film versions released first in Britain: Amanda Root starring in the lead role in the 1995 version co-starring Ciarán Hinds, and followed by Sally Hawkins starring in the 2007 version for ITV1 co-starring Rupert Penry-Jones.

Plot summary

The story begins seven years after the broken engagement of Anne Elliot to then Commander Frederick Wentworth. Anne Elliot, then 19 years old, fell in love and accepted a proposal of marriage from the handsome young naval officer. He was clever, confident, ambitious, and employed, but not yet wealthy and with no particular family connections to recommend him. Sir Walter, her father and her older sister Elizabeth maintained that he was no match for an Elliot of Kellynch Hall, the family estate. Lady Russell, acting in place of Anne's late mother, persuaded her to break the engagement, which she saw as imprudent for one so young. They are the only ones who know about this short engagement, as younger sister Mary was away at school.

The Elliot family is now in financial trouble. Kellynch Hall will be let, and the family will settle in Bath until finances improve. Baronet Sir Walter, the socially-conscious father and daughter Elizabeth look forward to the move. Anne is less sure she will enjoy Bath. Mary is married to Charles Musgrove of nearby Uppercross Hall, the heir to a respected local squire. Anne visits Mary and her family, where she is well-loved. The end of the war puts sailors back on shore, including the tenants of Kellynch Hall, Admiral Croft and his wife Sophia, who is the sister of Frederick Wentworth, now a wealthy naval captain. Frederick visits his sister and meets the Uppercross family, including Anne.

The Musgroves, including Mary, Charles, and Charles's sisters, Henrietta and Louisa, welcome the Crofts and Wentworth. He tells all he is ready to marry. Henrietta is engaged to her clergyman cousin Charles Hayter, who is away for the first few days that Wentworth joins their social circle. Both the Crofts and Musgroves enjoy speculating about which sister Wentworth might marry. Once Hayter returns, Henrietta turns her affections to him again. Anne still loves Wentworth, so each meeting with him requires preparation for her own strong emotions. She overhears a conversation where Louisa tells Wentworth that Charles first proposed to Anne, who turned him down. This is startling news to him.

Anne and the young adults of the Uppercross family accompany Captain Wentworth on a visit to two of his fellow officers, Captains Harville and James Benwick, in the coastal town of Lyme Regis. Benwick is in mourning for the death of his fiancée, Captain Harville's sister, and he appreciates Anne's sympathy and understanding. They both admire the Romantic poets. Anne attracts the attention of a gentleman passing through Lyme, who proves to be William Elliot, her cousin and the heir to Kellynch, who broke ties with Sir Walter years earlier. The last morning of the visit, Louisa sustains a serious concussion in a fall brought about by her impetuous behaviour with Wentworth. Anne coolly organizes the others to summon assistance. Wentworth is impressed with Anne, while feeling guilty about his actions with Louisa. He re-examines his feelings about Anne.

Following this accident, Anne joins her father and sister in Bath with Lady Russell, while Louisa and her parents stay at the Harvilles in Lyme. Wentworth visits his older brother in Shropshire. Anne finds that her father and sister are flattered by the attentions of William Elliot, recently widowed, who has reconciled with Sir Walter. Elizabeth assumes that he wishes to court her. Although Anne likes William Elliot and enjoys his manners, she finds his character opaque.

Admiral Croft and his wife arrive in Bath with the news that Louisa is engaged to Captain Benwick. Wentworth comes to Bath, where his jealousy is piqued by seeing Mr Elliot courting Anne. He and Anne renew their acquaintance. Anne visits an old school friend, Mrs Smith, who is now a widow living in Bath in straitened circumstances. From her she discovers that beneath his charming veneer, Mr Elliot is a cold, calculating opportunist who had led Mrs Smith's late husband into debt. As executor to her husband's will, he takes no actions to improve her situation. Although Mrs Smith believes that he is genuinely attracted to Anne, she feels that his first aim is preventing Mrs Clay from marrying Sir Walter. A new marriage might mean a new son, displacing him.

The Musgroves visit Bath to purchase wedding clothes for Louisa and Henrietta, both soon to marry. Captains Wentworth and Harville encounter them and Anne at the Musgroves' hotel in Bath, where Wentworth overhears Anne and Harville conversing about the relative faithfulness of men and women in love. Deeply moved by what Anne has to say about women not giving up their feelings of love even when all hope is lost, Wentworth writes her a note declaring his feelings for her. Outside the hotel, Anne and Wentworth reconcile, affirm their love for each other, and renew their engagement. William Elliot leaves Bath with Mrs Clay, whose charming ways may yet attract him. Lady Russell admits she was wrong about Wentworth, and befriends the new couple. Once Anne and Frederick marry, he helps Mrs Smith recover her lost assets. Anne settles into life as the wife of a Navy captain, he who is to be called away when his country needs him.

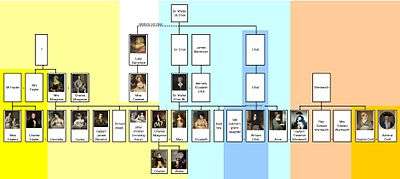

Main characters

Sir Walter Elliot, Bt. — A vain, self-satisfied baronet, Sir Walter's extravagance since the death of his prudent wife 13 years before has put his family in financial straits. These are severe enough to force him to lease his estate, Kellynch Hall, to Admiral Croft and take a more economical residence in Bath. Despite being strongly impressed by wealth and status he allows the insinuating Mrs Clay, who is beneath him in social standing, in his household as a companion to his eldest daughter.

Elizabeth Elliot — The eldest and most beautiful daughter of Sir Walter encourages her father's imprudent spending and extravagance. She and her father regard Anne as inconsequential. Elizabeth wants to marry, and has run the Elliot household since her mother died a dozen years earlier.

Anne Elliot — The second daughter of Sir Walter is intelligent, accomplished and attractive, and she is unmarried at 27, having broken off her engagement to Wentworth over seven years earlier. She fell in love with Captain Wentworth but was persuaded by her mentor, Lady Russell, to reject his proposal because of his poverty and uncertain future and her youth. Anne rejects a proposal a few years later, knowing she loves Wentworth.

Mary Musgrove — The youngest daughter of Sir Walter, married to Charles Musgrove, is attention-seeking, always looking for ways she might have been slighted or not given her full due, and often claims illness when she is upset. She opposes sister-in-law Henrietta's interest in marrying Charles Hayter, who Mary feels is beneath them.

Charles Musgrove — Husband of Mary and heir to the Musgrove estate. He first proposed to Anne, who said no. He married Mary about five years before the story opens, and they have two sons. He is a cheerful man, who loves hunting, and easily endures his wife's faults.

Lady Russell — A friend of the Elliots, particularly Anne, of whom she is the godmother. She is instrumental in Sir Walter's decision to leave Kellynch Hall and avoid financial crisis. Years earlier, she persuaded Anne to turn down Captain Wentworth's proposal of marriage. She was the intimate friend of the mother, and has watched over the three sisters since their mother died. She values social rank and finds in Anne the daughter most like her late friend.

Mrs Clay — A poor widow with children, daughter of Sir Walter's lawyer, and companion of Elizabeth Elliot. She aims to flatter Sir Walter into marriage, while her oblivious friend looks on.

Captain Frederick Wentworth — A naval officer who was briefly engaged to Anne some years ago. At the time, he had no fortune and uncertain prospects, but owing to his achievements in the Napoleonic Wars, he advanced in rank and in fortunes. He is one of two brothers of Sophia Croft. He gained his step to post Captain, and gained wealth amounting to about £25,000 from prize money awarded for capturing enemy vessels. He is an eminently eligible bachelor.

Admiral Croft — Good-natured, plainspoken tenant at Kellynch Hall and brother-in-law of Captain Wentworth. In his naval career, he was a captain when he married, present at the major battle of Trafalgar in 1805, then assigned in the east Indies, and holds the rank of rear admiral of the white.

Sophia Croft — Sister of Captain Wentworth and wife of Admiral Croft for the last 15 years. She is 38 years old. She offers Anne an example of a strong-minded woman who has married for love instead of money and who has a good life married to a Navy man.

Louisa Musgrove — Second sister of Charles Musgrove, Louisa, aged about 19, is a high-spirited young lady who has returned with her sister from school. She likes Captain Wentworth and seeks his attention. She is ultimately engaged to Captain Benwick, after recovering from her serious fall. Her brother Charles notices that she is less lively after suffering the concussion.

Henrietta Musgrove — Eldest sister of Charles Musgrove. Henrietta, aged about 20, is informally engaged to her cousin, Charles Hayter, but is nevertheless tempted by the more dashing Captain Wentworth. Once he returns home, she again connects with Hayter.

Captain Harville — A friend of Captain Wentworth. Wounded two years previously, he is slightly lame. Wentworth had not seen his friend since the time of that injury. Harville and his family are settled in nearby Lyme for the winter.

Captain James Benwick — A friend of Captains Harville and Wentworth. Benwick had been engaged to marry Captain Harville's sister Fanny, but she died while Benwick was at sea. He gained prize money as a lieutenant and not long after was promoted to commander (thus called Captain). Benwick's enjoyment of reading gives him a connection with Anne, as does her willingness to listen to him in his time of deep sadness. He might have enjoyed more time with her, before she returned to Lady Russell, but that did not occur. Benwick was with Louisa Musgrove the whole time of her recovery, at the end of which, they become engaged to marry.

Mr William Elliot — A distant relation ("great grandson of the second Sir Walter" when it is not stated from which Sir Walter the present one descends) and the heir presumptive of Sir Walter, Mr Elliot became estranged from the family when he wed a woman of lower social rank for her fortune and actively insulted Sir Walter. Sir Walter and Elizabeth had hoped William would marry Elizabeth Elliot. He is a widower, and now has interest in the social value of the title that he will someday inherit. He mends the rupture to keep an eye on the ambitious Mrs Clay. If Sir Walter married her, William's inheritance would be endangered. When Mr Elliot sees Anne by chance, and then learns she is Sir Walter's daughter, his interest is piqued: if he could marry Anne his title and inheritance likely would be secured because her father would be less inclined to disinherit his daughter. Rumors circulate in Bath that Anne and he are attached.

Mrs Smith — A friend of Anne Elliot who lives in Bath. Mrs Smith is a widow who suffers ill health and financial difficulties. She keeps abreast of the doings of Bath society through news she gets from her nurse, Rooke, who tends the wife of a friend of William Elliot's. Her financial problems could have been straightened out with assistance from William Elliot, her husband's friend and executor of his will, but Elliot would not exert himself, leaving her much impoverished. Wentworth eventually acts on her behalf.

Lady Dalrymple — A viscountess, cousin to Sir Walter. She occupies an exalted position in society by virtue of wealth and rank. Sir Walter and Elizabeth are eager to be seen at Bath in the company of this great relation.

Publication history

In a letter to her niece Fanny Knight in March 1817, Austen wrote about Persuasion that she had a novel "which may appear about a twelvemonth hence."[1] John Murray published Persuasion, together with Northanger Abbey, in a four-volume set, printed in December 1817 but dated 1818. The first advertisement appeared on December 17, 1817. The Austen family retained copyright of the 1,750 copies, which sold rapidly.[1]

Henry Austen supplied a "Biographical Notice" of his sister in which her identity is revealed and she is no longer an anonymous author.

Themes

Although readers of Persuasion might conclude that Austen intended "persuasion" to be the unifying theme of the story, the book's title is not hers but her brother Henry's, who named it after her untimely death. Certainly the idea of persuasion runs through the book, with vignettes within the story as variations on that theme. But there is no known source that documents what Austen intended to call her novel. Whatever her intentions might have been, she spoke of it as The Elliots, according to family tradition, and some critics believe that is probably the title she planned for it. As for Northanger Abbey, published at the same time, it was probably her brother Henry who chose that title as well.[2]

On the other hand, the literary scholar Gillian Beer establishes that Austen had profound concerns about the levels and applications of "persuasion" employed in society, especially as it related to the pressures and choices facing the young women of her day. Beer writes that for Austen and her readers, persuasion was indeed "fraught with moral dangers";[3]:xv she notes particularly that Austen personally was appalled by what she came to regard as her own misguided advice to her beloved niece Fanny Knight on the very question of whether Fanny ought to accept a particular suitor, even though it would have meant a protracted engagement. Beer writes:

Jane Austen's anxieties about persuasion and responsibility are here passionately expressed. She refuses to become part of the machinery with which Fanny is manoeuvering herself into forming the engagement. To be the stand-in motive for another's actions frightens her. Yet Jane Austen cannot avoid the part of persuader, even as dissuader.

Fanny ultimately rejected her suitor and after her aunt's death married someone else.[3]:x–xv

Thus, Beer explains, Austen was keenly aware that the human quality of persuasion—to persuade or to be persuaded, rightly or wrongly—is fundamental to the process of human communication, and that, in her novel "Jane Austen gradually draws out the implications of discriminating 'just' and 'unjust' persuasion." Indeed, the narrative winds through a number of situations in which people are influencing or attempting to influence other people—or themselves. Finally, Beer calls attention to "the novel's entire brooding on the power pressures, the seductions, and also the new pathways opened by persuasion".[3]:xv–xviii

Literary significance and criticism

A. Walton Litz in the essay titled "Persuasion: forms of estrangement," gives a concise summary of the various issues critics have raised with Persuasion as a novel.[4]

Persuasion has received highly intelligent criticism in recent years, after a long period of comparative neglect, and the lines of investigation have followed Virginia Woolf's suggestive comments. Critics have been concerned with the 'personal' quality of the novel and the problems it poses for biographical interpretation; with the obvious unevenness in narrative structure; with the 'poetic' use of landscape, and the hovering influence of Romantic poetry; with the pervasive presence of Anne Elliot's consciousness; with new effects in style and syntax; with the 'modernity' of Anne Elliot, an isolated personality in a rapidly changing society."

The literary scholar Stuart Tave in his essay concerning the main character Anne Elliot in Persuasion concentrated on the melancholy qualities of her reality in her world after she turns away the original proposal of marriage from Captain Wentworth. For Tave, Austen portrays Anne as a character with many admirable traits usually exceeding the quality of these traits as they are found in the other characters which surround her. Tave singles out Austen's portrayal of Anne at the end of the novel in her conversation with Captain Harville where the two of them discuss the relative virtues of gender and their advantages compared to one another, and Tave sees Anne as depicting a remarkable intelligence. Tave quotes from Virginia Woolf in her book A Room of One's Own where Woolf states, "It was strange to think that all the great women of fiction were, until Jane Austen's day, not only seen by the other sex, but seen only in relation to the other sex." Tave applies Woolf's insight to Persuasion when he continues: "All histories are against you, Captain Harville says to Anne in their disagreement about man's nature and woman's nature, 'all stories, prose and verse.' He could bring fifty quotations in a moment to his side of the argument, from books, songs, proverbs. But they were all written by men. 'Men have had every advantage of us in telling their own story,' as Anne says. Persuasion is the story told by a woman."[5]

In her book on Austen, the critic Julia Prewitt Brown found significance in the comparison of Persuasion to Austen's earlier novel Emma regarding Austen's ability to vary her narrative technique with respect to her authorial intentions. As Brown states:

"The coolness to the reader (conveyed by Austen's narrative) contrasts with an intensity of feeling for the characters in the story, particularly for the heroine. The reason for this contradiction is that Anne Elliot is the central intelligence of the novel. Sir Walter is seen as Anne sees him, with resigned contempt. For the first time Jane Austen gives over the narrator's authority to a character almost completely, In Emma, many events and situations are seen from Emma's point of view, but the central intelligence lies somewhere between the narrator and the reader, who together see that Emma sees wrongly. In Persuasion, Anne Elliot's feelings and evaluations correspond to those of the narrator in almost every situation, although there are several significant lapses... It seems that this transfer of authority placed a strain on Jane Austen's accustomed narrative tendencies and that she could not maintain it completely."[6]

Susan Morgan in her 1980 book on Austen challenges Litz on some assumptions in criticism concerning Austen's Persuasion when she states: "Singling out Persuasion as a novel which shows Austen's assimilation of the new romantic poetry brings more difficulties. Litz, commenting on 'the deeply physical impact of Persuasion', remarks that 'Mansfield Park is about the loss and return of principles, Emma about the loss and return of reason, Persuasion about the loss and return of 'bloom'.' Litz acknowledges the crudeness of these formulations and we recognize that he is attempting to discuss a quality of the novel which is hard to describe. But such summaries, even tentatively offered, only distort. The few brief nature scenes in Persuasion (and they are brief out of all proportion to the commentary on them), the walk to Winthrop and the environs of Pinny and Lyme, are certainly described with sensibility and appreciation. And in Anne's mind they are just as certainly bound up with 'the sweets of poetical despondence'."[7]

Although the impact of Austen's failing health at the time of writing Persuasion cannot be overlooked, the novel is strikingly original in several ways. It is the first of Austen's novels to feature as the central character a woman who, by the standards of the time, is past the first bloom of youth. Austen biographer Claire Tomalin characterises the book as Austen's "present to herself, to Miss Sharp, to Cassandra, to Martha Lloyd . . . to all women who had lost their chance in life and would never enjoy a second spring."[8]

The novel is described in the introduction to the Penguin Classics edition as a great Cinderella story. It features a heroine who is generally unappreciated and to some degree exploited by those around her; a handsome prince who appears on the scene but seems more interested in the "more obvious" charms of others; a moment of realisation; and the final happy ending. It has been said that it is not that Anne is unloved, but rather that those around her no longer see her clearly: she is such a fixed part of their lives that her likes and dislikes, wishes and dreams are no longer considered, even by those who claim to value her, like Lady Russell.

Early drafts and revisions

A. Walton Litz has emphasized the special quality of Austen's Persuasion among her novels in that it was written over a relatively narrow space of two or three years from start to finish. Almost all of Austen's novels were written in the form of first drafts (now lost) from before 1800 over a decade before their first publication in the last years of Austen's life. Since Persuasion was written over such a narrow time frame, Litz was able to locate and publish the early handwritten drafts of Austen as she refined the text of the novel into its final published form showing her meticulous attention to detail in editing her own writing. Litz citing the research of Norman Page gives an example of Austen's meticulous editing by excerpting a passage of Austen's cancelled Chapter Ten of the novel and comparing it to the revised version. In its original version, the manuscript stated:

"He found that he was considered by his friend Harville an engaged man. The Harvilles entertained not a doubt of a mutual attachment between him and Louisa; and though this to a degree was contradicted instantly, it yet made him feel that perhaps by her family, by everybody, by herself even, the same idea might be held, and that he was not free in honour, though if such were to be the conclusion, too free alas! in heart. He had never thought justly on this subject before, and he had not sufficiently considered that his excessive intimacy at Uppercross must have its danger of ill consequence in many ways; and that while trying whether he could attach himself to either of the girls, he might be exciting unpleasant reports if not raising unrequited regard./ He found too late that he had entangled himself" (cancelled version, as published in Chapman's edition of Austen).

Litz then gives the final version by Austen:

"'I found', said he, 'that I was considered by Harville an engaged man! That neither Harville nor his wife entertained a doubt of our mutual attachment. I was startled and shocked. To a degree, I could contradict this instantly; but, when I began to reflect that others might have felt the same -- her own family, nay, perhaps herself, I was no longer at my own disposal. I was hers in honour if she wished it. I had been unguarded. I had not thought seriously on this subject before. I had not considered that my excessive intimacy must have its danger of ill consequence in many ways; and that I had no right to be trying whether I could attach myself to either of the girls, at the risk of raising even an unpleasant report, were there no other ill effects. I had been grossly wrong, and must abide the consequences.'/ He found too late, in short, that he had entangled himself" (final version).

To this may be added the surviving version of Austen's handwritten copy of the original draft before the editing process outlined above had even started where Austen wrote it in the following nascent form:

"He found that he was considered by his friend Harville, as an engaged Man. The Harvilles entertained not a doubt of a mutual attachment between him & Louisa -- and though this to a degree was contradicted instantly -- it yet made him feel that perhaps by her family, be everyone, by herself even, the same idea might be held -- and that he was not free' alas! in Heart. -- He had never thought justly on this subject before -- he had not sufficiently considered that this excessive Intimacy at Uppercross must have it's danger of ill consequence in many ways, and that while trying whether he c-d (sic) attach himself to either of the Girls, he might be exciting unpleasant reports, if not, raising unrequited regard! -- He found, too late, that he had entangled himself --."

Persuasion is unique among Austen's novels in allowing such a close inspection, as recorded by Litz, of her editorial prowess in revising and enhancing early drafts of her own writing.[4]

Adaptations

Persuasion has been the subject of several adaptations.

Television

- 1960: Persuasion, BBC miniseries starring Daphne Slater as Anne and Paul Daneman as Captain Wentworth.

- 1971: Persuasion, ITV miniseries starring Anne Firbank as Anne and Bryan Marshall as Captain Wentworth.

- 1995: Persuasion, made-for-television film (which was released in US theatres by Sony Pictures Classics) starring Amanda Root as Anne and Ciarán Hinds as Captain Wentworth.

- 2007: Persuasion, teleplay, filmed in Bath in September 2006 for ITV1, with Sally Hawkins as Anne, Rupert Penry-Jones as Captain Wentworth.

Theatre

- 2010: Persuasion, a musical drama adapted from the novel by Barbara Landis, using music from the period selected from Austen's own writings. It was performed by Chamber Opera Chicago first in 2011,[9] again in 2013[10] and subsequently performed by the same company in New York and several cities in the United Kingdom, in 2013 through 2015.[11]

- 2011: An adaptation for the stage of Persuasion by Tim Luscombe, was produced by Salisbury Playhouse (Repertory Theatre).[12] in 2011.[13]

- 2012: Persuasion, adapted for the theatre by Jon Jory, world-premiere at Onstage Playhouse in Chula Vista, CA

References

- 1 2 Gilson, David (1986). Grey, J. David, ed. Editions and Publishing History. The Jane Austen Companion. New York: Macmillan. pp. 135–139. ISBN 0-025-45540-0.

- ↑ Le Faye, Deirdre (2003). Jane Austen: The World of Her Novels. London: Francis Lincoln. p. 278. ISBN 978-0711222786.

- 1 2 3 Beer, Gillian (1998). Introduction. Persuasion. By Austen, Jane. London: Penguin Classics. ISBN 978-0140434675.

- 1 2 Litz, A. Walton (1975). "Persuasion: forms of estrangement". In Halperin, John. Jane Austen: Bicentenary Essays. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0521099295.

- ↑ Tave, Stuart (1973). "Anne Elliot, Whose Word Had No Weight". Some Words of Jane Austen. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0226790169.

- ↑ Brown, Julia Prewitt (1979). Jane Austen's Novels: Social Change and Literary Form. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0674471726.

- ↑ Morgan, Susan (15 February 1980). In the Meantime: Character and Perception in Jane Austen's Fiction. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226537634.

- ↑ Tomalin, Claire (1997). Jane Austen: A Life. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 256. ISBN 0-679-44628-1.

- ↑ Bresloff, Alan (12 September 2011). "Jane Austen's "Persuasion"". Around the Town Chicago. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ "Jane Austen's Persuasion, Newly Adapted as a Musical – Discount Tickets at Royal George Theater". Style Chicago. September 2013. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Dibdin, Thom (7 August 2015). "Jane Austen's Persuasion". All Edinburgh Theatre. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ Luscombe, Tim (2011). "Persuasion by Jane Austen". Salisbury UK. Retrieved 11 August 2016.

- ↑ Luscombe, Tim (2011). Persuasion by Jane Austen in a new adaptation. London: Oberon Books. ISBN 978-1849431934. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Persuasion (novel) |

- Persuasion at Project Gutenberg

-

Persuasion public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Persuasion public domain audiobook at LibriVox - Persuasion Gazetteer, A Guide to the Real and Imagined Places in the Novel

_hires.jpg)

.jpg)