Childbirth

| Childbirth | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | partus, parturition, birth |

| |

| Newborn infant and mother | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Obstetrics, midwifery |

Childbirth, also known as labour and delivery, is the ending of a pregnancy by one or more babies leaving a woman's uterus.[1] In 2015 there were about 135 million births globally.[2] About 15 million were born before 37 weeks of gestation,[3] while between 3 and 12% were born after 42 weeks.[4] In the developed world most deliveries occur in hospital,[5][6] while in the developing world most births take place at home with the support of a traditional birth attendant.[7]

The most common way of childbirth is a vaginal delivery.[8] It involves three stages of labour: the shortening and opening of the cervix, descent and birth of the baby, and the pushing out of the placenta.[9] The first stage typically lasts twelve to nineteen hours, the second stage twenty minutes to two hours, and the third stage five to thirty minutes.[10] The first stage begins with crampy abdominal or back pains that last around half a minute and occur every ten to thirty minutes.[9] The crampy pains become stronger and closer together over time.[10] During the second stage pushing with contractions may occur.[10] In the third stage delayed clamping of the umbilical cord is generally recommended.[11] A number of methods can help with pain such as relaxation techniques, opioids, and spinal blocks.[10]

Most babies are born head first; however about 4% are born feet or buttock first, known as breech.[10][12] During labour a women can generally eat and move around as she likes, pushing is not recommended during the first stage or during delivery of the head, and enemas are not recommended.[13] While making a cut to the opening of the vagina is common, known as an episiotomy, it is generally not needed.[10] In 2012, about 23 million deliveries occurred by a surgical procedure known as Caesarean section.[14] Caesarean sections may be recommended for twins, signs of distress in the baby, or breech position.[10] This method of delivery can take longer to heal from.[10]

Each year complications from pregnancy and childbirth result in about 500,000 maternal deaths, 7 million women have serious long term problems, and 50 million women have health negative outcomes following delivery.[15] Most of these occur in the developing world.[15] Specific complications include obstructed labour, postpartum bleeding, eclampsia, and postpartum infection.[15] Complications in the baby include birth asphyxia.[16]

Signs and symptoms

.jpg)

The most prominent sign of labour is strong repetitive uterine contractions. The distress levels reported by labouring women vary widely. They appear to be influenced by fear and anxiety levels, experience with prior childbirth, cultural ideas of childbirth and pain,[17][18] mobility during labour, and the support received during labour. Personal expectations, the amount of support from caregivers, quality of the caregiver-patient relationship, and involvement in decision-making are more important in women's overall satisfaction with the experience of childbirth than are other factors such as age, socioeconomic status, ethnicity, preparation, physical environment, pain, immobility, or medical interventions.[19]

Descriptions

Pain in contractions has been described as feeling similar to very strong menstrual cramps. Women are often encouraged to refrain from screaming, but moaning and grunting may be encouraged to help lessen pain. Crowning may be experienced as an intense stretching and burning. Even women who show little reaction to labour pains, in comparison to other women, show a substantially severe reaction to crowning.

Back labour is a term for specific pain occurring in the lower back, just above the tailbone, during childbirth.[20]

Psychological

Childbirth can be an intense event and strong emotions, both positive and negative, can be brought to the surface. Abnormal and persistent fear of childbirth is known as tokophobia.

During the later stages of gestation there is an increase in abundance of oxytocin, a hormone that is known to evoke feelings of contentment, reductions in anxiety, and feelings of calmness and security around the mate.[21] Oxytocin is further released during labour when the fetus stimulates the cervix and vagina, and it is believed that it plays a major role in the bonding of a mother to her infant and in the establishment of maternal behavior. The act of nursing a child also causes a release of oxytocin.[22]

Between 70% and 80% of mothers in the United States report some feelings of sadness or "baby blues" after giving birth. The symptoms normally occur for a few minutes up to few hours each day and they should lessen and disappear within two weeks after delivery. Postpartum depression may develop in some women; about 10% of mothers in the United States are diagnosed with this condition. Preventive group therapy has proven effective as a prophylactic treatment for postpartum depression.[23][24]

Normal birth

Humans are bipedal with an erect stance. The erect posture causes the weight of the abdominal contents to thrust on the pelvic floor, a complex structure which must not only support this weight but allow, in women, three channels to pass through it: the urethra, the vagina and the rectum. The infant's head and shoulders must go through a specific sequence of maneuvers in order to pass through the ring of the mother's pelvis.

Six phases of a typical vertex (head-first presentation) delivery:

- Engagement of the fetal head in the transverse position. The baby's head is facing across the pelvis at one or other of the mother's hips.

- Descent and flexion of the fetal head.

- Internal rotation. The fetal head rotates 90 degrees to the occipito-anterior position so that the baby's face is towards the mother's rectum.

- Delivery by extension. The fetal head passes out of the birth canal. Its head is tilted forwards so that the crown of its head leads the way through the vagina.

- Restitution. The fetal head turns through 45 degrees to restore its normal relationship with the shoulders, which are still at an angle.

- External rotation. The shoulders repeat the corkscrew movements of the head, which can be seen in the final movements of the fetal head.

Station refers to the relationship of the fetal presenting part to the level of the ischial spines. When the presenting part is at the ischial spines the station is 0 (synonymous with engagement). If the presenting fetal part is above the spines, the distance is measured and described as minus stations, which range from –1 to –4 cm. If the presenting part is below the ischial spines, the distance is stated as plus stations ( +1 to +4 cm). At +3 and +4 the presenting part is at the perineum and can be seen.[25]

The fetal head may temporarily change shape substantially (becoming more elongated) as it moves through the birth canal. This change in the shape of the fetal head is called molding and is much more prominent in women having their first vaginal delivery.[26]

Onset of labour

There are various definitions of the onset of labour, including:

- Regular uterine contractions at least every six minutes with evidence of change in cervical dilation or cervical effacement between consecutive digital examinations.[27]

- Regular contractions occurring less than 10 min apart and progressive cervical dilation or cervical effacement.[28]

- At least 3 painful regular uterine contractions during a 10-minute period, each lasting more than 45 seconds.[29]

In order to avail for more uniform terminology, the first stage of labour is divided into "latent" and "active" phases, where the latent phase is sometimes included in the definition of labour,[30] and sometimes not.[31]

Some reports note that the onset of term labour more commonly takes place in the late night and early morning hours. This may be a result of a synergism between the nocturnal increase in melatonin and oxytocin.[32]

First stage: latent phase

The latent phase of labour is also called the quiescent phase, prodromal labour, or pre-labour. It is a subclassification of the first stage.[33]

The latent phase is generally defined as beginning at the point at which the woman perceives regular uterine contractions.[34] In contrast, Braxton Hicks contractions, which are contractions that may start around 26 weeks gestation and are sometimes called "false labour", should be infrequent, irregular, and involve only mild cramping.[35] The signaling mechanisms responsible for uterine coordination are complex. Electrical propagation is the primary mechanism used for signaling up to several centimeters. Over longer distances, however, signaling may involve a mechanical mechanism.[36]

Cervical effacement, which is the thinning and stretching of the cervix, and cervical dilation occur during the closing weeks of pregnancy and is usually complete or near complete, by the end of the latent phase. The degree of cervical effacement may be felt during a vaginal examination. A 'long' cervix implies that effacement has not yet occurred. Latent phase ends with the onset of active first stage, and this transition is defined retrospectively.

First stage: active phase

The active stage of labour (or "active phase of first stage" if the previous phase is termed "latent phase of first stage") has geographically differing definitions. In the US, the definition of active labour was changed from 3 to 4 cm, to 5 cm of cervical dilation for multiparous women, mothers who had given birth previously, and at 6 cm for nulliparous women, those who had not given birth before.[37] This has been done in an effort to increase the rates of vaginal delivery.[38]

A definition of active labour in a British journal was having contractions more frequent than every 5 minutes, in addition to either a cervical dilation of 3 cm or more or a cervical effacement of 80% or more.[39]

In Sweden, the onset of the active phase of labour is defined as when two of the following criteria are met:[40]

- three to four contractions every ten minutes

- rupture of membranes

- cervical dilation of 3 to 4 cm

Health care providers may assess a labouring mother's progress in labour by performing a cervical exam to evaluate the cervical dilation, effacement, and station. These factors form the Bishop score. The Bishop score can also be used as a means to predict the success of an induction of labour.

During effacement, the cervix becomes incorporated into the lower segment of the uterus. During a contraction, uterine muscles contract causing shortening of the upper segment and drawing upwards of the lower segment, in a gradual expulsive motion. The presenting fetal part then is permitted to descend. Full dilation is reached when the cervix has widened enough to allow passage of the baby's head, around 10 cm dilation for a term baby.

The duration of labour varies widely, but the active phase averages some 8 hours[41] for women giving birth to their first child ("primiparae") and shorter for women who have already given birth ("multiparae"). Active phase prolongation is defined as in a primigravid woman as the failure of the cervix to dilate at a rate of 1.2 cm/h over a period of at least two hours. This definition is based on Friedman's Curve, which plots the typical rate of cervical dilation and fetal descent during active labour.[42] Some practitioners may diagnose "Failure to Progress", and consequently, propose interventions to optimize chances for healthy outcome.[43]

Second stage: fetal expulsion

The expulsion stage (stimulated by prostaglandins and oxytocin) begins when the cervix is fully dilated, and ends when the baby is born. As pressure on the cervix increases, women may have the sensation of pelvic pressure and an urge to begin pushing. At the beginning of the normal second stage, the head is fully engaged in the pelvis; the widest diameter of the head has passed below the level of the pelvic inlet. The fetal head then continues descent into the pelvis, below the pubic arch and out through the vaginal introitus (opening). This is assisted by the additional maternal efforts of "bearing down" or pushing. The appearance of the fetal head at the vaginal orifice is termed the "crowning". At this point, the woman will feel an intense burning or stinging sensation.

When the amniotic sac has not ruptured during labour or pushing, the infant can be born with the membranes intact. This is referred to as "delivery en caul".

Complete expulsion of the baby signals the successful completion of the second stage of labour.

The second stage of birth will vary by factors including parity (the number of children a woman has had), fetal size, anesthesia, and the presence of infection. Longer labours are associated with declining rates of spontaneous vaginal delivery and increasing rates of infection, perineal laceration, and obstetric hemorrhage, as well as the need for intensive care of the neonate.[44]

Third stage: placenta delivery

The period from just after the fetus is expelled until just after the placenta is expelled is called the third stage of labour or the involution stage. Placental expulsion begins as a physiological separation from the wall of the uterus. The average time from delivery of the baby until complete expulsion of the placenta is estimated to be 10–12 minutes dependent on whether active or expectant management is employed[45] In as many as 3% of all vaginal deliveries, the duration of the third stage is longer than 30 minutes and raises concern for retained placenta.[46]

Placental expulsion can be managed actively or it can be managed expectantly, allowing the placenta to be expelled without medical assistance. Active management is described as the administration of a uterotonic drug within one minute of fetal delivery, controlled traction of the umbilical cord and fundal massage after delivery of the placenta, followed by performance of uterine massage every 15 minutes for two hours.[47] In a joint statement, World Health Organization, the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics and the International Confederation of Midwives recommend active management of the third stage of labour in all vaginal deliveries to help to prevent postpartum hemorrhage.[48][49][50]

Delaying the clamping of the umbilical cord until at least one minute after birth improves outcomes as long as there is the ability to treat jaundice if it occurs.[51] In some birthing centers, this may be delayed by 5 minutes or more, or omitted entirely. Delayed clamping of the cord decreases the risk of anemia but may increase risk of jaundice. Clamping is followed by cutting of the cord, which is painless due to the absence of nerves.

Fourth stage

The "fourth stage of labour" is the period beginning immediately after the birth of a child and extending for about six weeks. The terms postpartum and postnatal are often used to describe this period.[52] It is the time in which the mother's body, including hormone levels and uterus size, return to a non-pregnant state and the newborn adjusts to life outside the mother's body. The World Health Organization (WHO) describes the postnatal period as the most critical and yet the most neglected phase in the lives of mothers and babies; most deaths occur during the postnatal period.[53]

Following the birth, if the mother had an episiotomy or a tearing of the perineum, it is stitched. The mother should have regular assessments for uterine contraction and fundal height,[54] vaginal bleeding, heart rate and blood pressure, and temperature, for the first 24 hours after birth. The first passing of urine should be documented within 6 hours.[53] Afterpains (pains similar to menstrual cramps), contractions of the uterus to prevent excessive blood flow, continue for several days. Vaginal discharge, termed "lochia", can be expected to continue for several weeks; initially bright red, it gradually becomes pink, changing to brown, and finally to yellow or white.[55]

Most authorities suggest the infant be placed in skin-to-skin contact with the mother for 1 –2 hours immediately after birth, putting routine cares off till later.

Until recently babies born in hospitals were removed from their mothers shortly after birth and brought to the mother only at feeding times. Mothers were told that their newborn would be safer in the nursery and that the separation would offer the mother more time to rest. As attitudes began to change, some hospitals offered a "rooming in" option wherein after a period of routine hospital procedures and observation, the infant could be allowed to share the mother's room. However, more recent information has begun to question the standard practice of removing the newborn immediately postpartum for routine postnatal procedures before being returned to the mother. Beginning around 2000, some authorities began to suggest that early skin-to-skin contact (placing the naked baby on the mother's chest) may benefit both mother and infant. Using animal studies that have shown that the intimate contact inherent in skin-to-skin contact promotes neurobehaviors that result in the fulfillment of basic biological needs as a model, recent studies have been done to assess what, if any, advantages may be associated with early skin-to-skin contact for human mothers and their babies. A 2011 medical review looked at existing studies and found that early skin-to-skin contact, sometimes called kangaroo care, resulted in improved breastfeeding outcomes, cardio-respiratory stability, and a decrease in infant crying. [56][57][58] A 2007 Cochrane review of studies found that skin-to-skin contact at birth reduced crying, kept the baby warmer, improved mother-baby interaction, and improved the chances for successful breastfeeding.[59]

As of 2014, early postpartum skin-to-skin contact is endorsed by all major organizations that are responsible for the well-being of infants, including the American Academy of Pediatrics.[60] The World Health Organization (WHO) states that "the process of childbirth is not finished until the baby has safely transferred from placental to mammary nutrition." They advise that the newborn be placed skin-to-skin with the mother, postponing any routine procedures for at least one to two hours. The WHO suggests that any initial observations of the infant can be done while the infant remains close to the mother, saying that even a brief separation before the baby has had its first feed can disturb the bonding process. They further advise frequent skin-to-skin contact as much as possible during the first days after delivery, especially if it was interrupted for some reason after the delivery.[61] The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence also advises postponing procedures such as weighing, measuring, and bathing for at least 1 hour to insure an initial period of skin-to-skin contact between mother and infant. [62]

Management

Deliveries are assisted by a number of professions include: obstetricians, family physicians and midwives. For low risk pregnancies all three result in similar outcomes.[63]

Preparation

Eating or drinking during labour is an area of ongoing debate. While some have argued that eating in labour has no harmful effects on outcomes,[64] others continue to have concern regarding the increased possibility of an aspiration event (choking on recently eaten foods) in the event of an emergency delivery due to the increased relaxation of the esophagus in pregnancy, upward pressure of the uterus on the stomach, and the possibility of general anesthetic in the event of an emergency cesarean.[65] A 2013 Cochrane review found that with good obstetrical anaesthesia there is no change in harms from allowing eating and drinking during labour in those who are unlikely to need surgery. They additionally acknowledge that not eating does not mean there is an empty stomach or that its contents are not as acidic. They therefore conclude that "women should be free to eat and drink in labour, or not, as they wish."[66]

At one time shaving of the area around the vagina, was common practice due to the belief that hair removal reduced the risk of infection, made an episiotomy (a surgical cut to enlarge the vaginal entrance) easier, and helped with instrumental deliveries. It is currently less common, though it is still a routine procedure in some countries. A 2009 Cochrane review found no evidence of any benefit with perineal shaving. The review did find side effects including irritation, redness, and multiple superficial scratches from the razor.[67] Another effort to prevent infection has been the use of the antiseptic chlorhexidine or providone-iodine solution in the vagina. Evidence of benefit with chlorhexidine is lacking.[68] A decreased risk is found with providone-iodine when a cesarean section is to be performed.[69]

Active management

Active management of labour consists of a number of care principles, including frequent assessment of cervical dilatation. If the cervix is not dilating, oxytocin is offered. This management results in a slightly reduced number of caesarean births, but does not change how many women have assisted vaginal births. 75% of women report that they are very satisfied with either active management or normal care.[70]

Labour induction and elective cesarean

In many cases and with increasing frequency, childbirth is achieved through induction of labour or caesarean section. Caesarean section is the removal of the neonate through a surgical incision in the abdomen, rather than through vaginal birth.[71] Childbirth by C-Sections increased 50% in the U.S. from 1996 to 2006, and comprise nearly 32% of births in the U.S. and Canada.[71][72] Induced births and elective cesarean before 39 weeks can be harmful to the neonate as well as harmful or without benefit to the mother. Therefore, many guidelines recommend against non-medically required induced births and elective cesarean before 39 weeks.[73] The rate of labour induction in the United States is 22%, and has more than doubled from 1990 to 2006.[74][75]

Health conditions that may warrant induced labour or cesarean delivery include gestational or chronic hypertension, preeclampsia, eclampsia, diabetes, premature rupture of membranes, severe fetal growth restriction, and post-term pregnancy. Cesarean section too may be of benefit to both the mother and baby for certain indications including maternal HIV/AIDS, fetal abnormality, breech position, fetal distress, multiple gestations, and maternal medical conditions which would be worsened by labour or vaginal birth.

Pitocin is the most commonly used agent for induction in the United States, and is used to induce uterine contractions. Other methods of inducing labour include stripping of the amniotic membrane, artificial rupturing of the amniotic sac (called amniotomy), or nipple stimulation. Ripening of the cervix can be accomplished with the placement of a Foley catheter or the use of synthetic prostaglandins such as misoprostol.[74] A large review of methods of induction was published in 2011.[76]

The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines recommend a full evaluation of the maternal-fetal status, the status of the cervix, and at least a 39 completed weeks (full term) of gestation for optimal health of the newborn when considering elective induction of labour. Per these guidelines, the following conditions may be an indication for induction, including:

- Abruptio placentae

- Chorioamnionitis

- Fetal compromise such as isoimmunization leading to hemolytic disease of the newborn or oligohydramnios

- Fetal demise

- Gestational hypertension

- Maternal conditions such as gestational diabetes or chronic kidney disease

- Preeclampsia or eclampsia

- Premature rupture of membranes

- Postterm pregnancy

Induction is also considered for logistical reasons, such as the distance from hospital or psychosocial conditions, but in these instances gestational age confirmation must be done, and the maturity of the fetal lung must be confirmed by testing.

The ACOG also note that contraindications for induced labour are the same as for spontaneous vaginal delivery, including vasa previa, complete placenta praevia, umbilical cord prolapse or active genital herpes simplex infection.[77]

Pain control

Non pharmaceutical

Some women prefer to avoid analgesic medication during childbirth. Psychological preparation may be beneficial.[78] A recent Cochrane overview of systematic reviews on non-drug interventions found that relaxation techniques, immersion in water, massage, and acupuncture may provide pain relief. Acupuncture and relaxation were found to decrease the number of caesarean sections required.[79] Immersion in water has been found to relieve pain during the first stage of labor and to reduce the need for anesthesia and shorten the duration of labor, however the safety and efficacy of immersion during birth, water birth, has not been established or associated with maternal or fetal benefit.[80]

Some women like to have someone to support them during labour and birth; such as a midwife, nurse, or doula; or a lay person such as the father of the baby, a family member, or a close friend. Studies have found that continuous support during labor and delivery reduce the need for medication and a caesarean or operative vaginal delivery, and result in an improved Apgar score for the infant.[81] [82]

The injection of small amounts of sterile water into or just below the skin at several points on the back has been a method tried to reduce labour pain, but no good evidence shows that it actually helps.[83]

Pharmaceutical

Different measures for pain control have varying degrees of success and side effects to the woman and her baby. In some countries of Europe, doctors commonly prescribe inhaled nitrous oxide gas for pain control, especially as 53% nitrous oxide, 47% oxygen, known as Entonox; in the UK, midwives may use this gas without a doctor's prescription. Opioids such as fentanyl may be used, but if given too close to birth there is a risk of respiratory depression in the infant.

Popular medical pain control in hospitals include the regional anesthetics epidurals (EDA), and spinal anaesthesia. Epidural analgesia is a generally safe and effective method of relieving pain in labour, but is associated with longer labour, more operative intervention (particularly instrument delivery), and increases in cost.[84] Generally, pain and stress hormones rise throughout labour for women without epidurals, while pain, fear, and stress hormones decrease upon administration of epidural analgesia, but rise again later.[85] Medicine administered via epidural can cross the placenta and enter the bloodstream of the fetus.[86] Epidural analgesia has no statistically significant impact on the risk of caesarean section, and does not appear to have an immediate effect on neonatal status as determined by Apgar scores.[87]

Augmentation

Augmentation is the process of facilitating further labour. Oxytocin has been used to increase the rate of vaginal delivery in those with a slow progress of labour.[88]

Administration of antispasmodics (e.g. hyoscine butylbromide) is not formally regarded as augmentation of labour; however, there is weak evidence that they may shorten labour.[89] There is not enough evidence to make conclusions about unwanted effects in mothers or babies.[89]

Episiotomy

Vaginal tears can occur during childbirth, most often at the vaginal opening as the baby's head passes through, especially if the baby descends quickly. Tears can involve the perineal skin or extend to the muscles and the anal sphincter and anus. The midwife or obstetrician may decide to make a surgical cut to the perineum (episiotomy) to make the baby's birth easier and prevent severe tears that can be difficult to repair. A 2012 Cochrane review compared episiotomy as needed (restrictive) with routine episiotomy to determine the possible benefits and harms for mother and baby. The review found that restrictive episiotomy policies appeared to give a number of benefits compared with using routine episiotomy. Women experienced less severe perineal trauma, less posterior perineal trauma, less suturing and fewer healing complications at seven days with no difference in occurrence of pain, urinary incontinence, painful sex or severe vaginal/perineal trauma after birth, however they found that women experienced more anterior perineal damage with restrictive episiotomy.[90]

Instrumental delivery

Obstetric forceps or ventouse may be used to facilitate childbirth.

Multiple births

In cases of a cephalic presenting twin (first baby head down), twins can often be delivered vaginally. In some cases twin delivery is done in a larger delivery room or in an operating theatre, in the event of complication e.g.

- Both twins born vaginally—this can occur both presented head first or where one comes head first and the other is breech and/or helped by a forceps/ventouse delivery

- One twin born vaginally and the other by caesarean section.

- If the twins are joined at any part of the body—called conjoined twins, delivery is mostly by caesarean section.

Support

Historically women have been attended and supported by other women during labour and birth. However currently, as more women are giving birth in a hospital rather than at home, continuous support has become the exception rather than the norm. When women became pregnant any time before the 1950s the husband would not be in the birthing room. It did not matter if it was a home birth; the husband was waiting downstairs or in another room in the home. If it was in a hospital then the husband was in the waiting room. "Her husband was attentive and kind, but, Kirby concluded, Every good woman needs a companion of her own sex."[91] Obstetric care frequently subjects women to institutional routines, which may have adverse effects on the progress of labour. Supportive care during labour may involve emotional support, comfort measures, and information and advocacy which may promote the physical process of labour as well as women's feelings of control and competence, thus reducing the need for obstetric intervention. The continuous support may be provided either by hospital staff such as nurses or midwives, doulas, or by companions of the woman's choice from her social network. There is increasing evidence to show that the participation of the child's father in the birth leads to better birth and also post-birth outcomes, providing the father does not exhibit excessive anxiety.[92]

A recent Cochrane review involving more than 15,000 women in a wide range of settings and circumstances found that "Women who received continuous labour support were more likely to give birth 'spontaneously', i.e. give birth with neither caesarean nor vacuum nor forceps. In addition, women were less likely to use pain medications, were more likely to be satisfied, and had slightly shorter labours. Their babies were less likely to have low five-minute Apgar scores."[81]

Fetal monitoring

External monitoring

For monitoring of the fetus during childbirth, a simple pinard stethoscope or doppler fetal monitor ("doptone") can be used. A method of external (noninvasive) fetal monitoring (EFM) during childbirth is cardiotocography, using a cardiotocograph that consists of two sensors: The heart (cardio) sensor is an ultrasonic sensor, similar to a Doppler fetal monitor, that continuously emits ultrasound and detects motion of the fetal heart by the characteristic of the reflected sound. The pressure-sensitive contraction transducer, called a tocodynamometer (toco) has a flat area that is fixated to the skin by a band around the belly. The pressure required to flatten a section of the wall correlates with the internal pressure, thereby providing an estimate of contraction[93] Monitoring with a cardiotocograph can either be intermittent or continuous.

Internal monitoring

A mother's water has to break before internal (invasive) monitoring can be used. More invasive monitoring can involve a fetal scalp electrode to give an additional measure of fetal heart activity, and/or intrauterine pressure catheter (IUPC). It can also involve fetal scalp pH testing.

Collecting stem cells

It is currently possible to collect two types of stem cells during childbirth: amniotic stem cells and umbilical cord blood stem cells.[94] They are being studied as possible treatments of a number of conditions.[94]

Complications

The "natural" maternal mortality rate of childbirth—where nothing is done to avert maternal death—has been estimated at 1500 deaths per 100,000 births.[96] (See main articles: neonatal death, maternal death). Each year about 500,000 women die due to pregnancy, 7 million have serious long term complications, and 50 million have negative outcomes following delivery.[15]

Modern medicine has decreased the risk of childbirth complications. In Western countries, such as the United States and Sweden, the current maternal mortality rate is around 10 deaths per 100,000 births.[96]:p.10 As of June 2011, about one third of American births have some complications, "many of which are directly related to the mother's health."[97]

Birthing complications may be maternal or fetal, and long term or short term.

Pre-term

Newborn mortality at 37 weeks may be 2.5 times the number at 40 weeks, and was elevated compared to 38 weeks of gestation. These "early term" births were also associated with increased death during infancy, compared to those occurring at 39 to 41 weeks ("full term").[73] Researchers found benefits to going full term and "no adverse effects" in the health of the mothers or babies.[73]

Medical researchers find that neonates born before 39 weeks experienced significantly more complications (2.5 times more in one study) compared with those delivered at 39 to 40 weeks. Health problems among babies delivered "pre-term" included respiratory distress, jaundice and low blood sugar.[73][98] The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and medical policy makers review research studies and find increased incidence of suspected or proven sepsis, RDS, Hypoglycemia, need for respiratory support, need for NICU admission, and need for hospitalization > 4 – 5 days. In the case of cesarean sections, rates of respiratory death were 14 times higher in pre-labour at 37 compared with 40 weeks gestation, and 8.2 times higher for pre-labour cesarean at 38 weeks. In this review, no studies found decreased neonatal morbidity due to non-medically indicated (elective) delivery before 39 weeks.[73]

Labour complications

The second stage of labour may be delayed or lengthy due to:

- malpresentation (breech birth (i.e. buttocks or feet first), face, brow, or other)

- failure of descent of the fetal head through the pelvic brim or the interspinous diameter

- poor uterine contraction strength

- active phase arrest

- cephalo-pelvic disproportion (CPD)

- shoulder dystocia

Secondary changes may be observed: swelling of the tissues, maternal exhaustion, fetal heart rate abnormalities. Left untreated, severe complications include death of mother and/or baby, and genitovaginal fistula.

Obstructed labour

Obstructed labour, also known as labor dystocia, is when, even though the uterus is contracting normally, the baby does not exit the pelvis during childbirth due to being physically blocked.[99] Prolonged obstructed labor can result in obstetric fistula, a complication of childbirth where tissue death preforates the rectum or bladder.

Maternal complications

Vaginal birth injury with visible tears or episiotomies are common. Internal tissue tearing as well as nerve damage to the pelvic structures lead in a proportion of women to problems with prolapse, incontinence of stool or urine and sexual dysfunction. Fifteen percent of women become incontinent, to some degree, of stool or urine after normal delivery, this number rising considerably after these women reach menopause. Vaginal birth injury is a necessary, but not sufficient, cause of all non hysterectomy related prolapse in later life. Risk factors for significant vaginal birth injury include:

- A baby weighing more than 9 pounds.

- The use of forceps or vacuum for delivery. These markers are more likely to be signals for other abnormalities as forceps or vacuum are not used in normal deliveries.

- The need to repair large tears after delivery.

There is tentative evidence that antibiotics may help prevent wound infections in women with third or fourth degree tears.[100]

Pelvic girdle pain. Hormones and enzymes work together to produce ligamentous relaxation and widening of the symphysis pubis during the last trimester of pregnancy. Most girdle pain occurs before birthing, and is known as diastasis of the pubic symphysis. Predisposing factors for girdle pain include maternal obesity.

Infection remains a major cause of maternal mortality and morbidity in the developing world. The work of Ignaz Semmelweis was seminal in the pathophysiology and treatment of puerperal fever and saved many lives.

Hemorrhage, or heavy blood loss, is still the leading cause of death of birthing mothers in the world today, especially in the developing world. Heavy blood loss leads to hypovolemic shock, insufficient perfusion of vital organs and death if not rapidly treated. Blood transfusion may be life saving. Rare sequelae include Hypopituitarism Sheehan's syndrome.

The maternal mortality rate (MMR) varies from 9 per 100,000 live births in the US and Europe to 900 per 100,000 live births in Sub-Saharan Africa.[101] Every year, more than half a million women die in pregnancy or childbirth.[102]

Fetal complications

Mechanical fetal injury

Risk factors for fetal birth injury include fetal macrosomia (big baby), maternal obesity, the need for instrumental delivery, and an inexperienced attendant. Specific situations that can contribute to birth injury include breech presentation and shoulder dystocia. Most fetal birth injuries resolve without long term harm, but brachial plexus injury may lead to Erb's palsy or Klumpke's paralysis.[103]

Neonatal infection

_conditions_world_map_-_DALY_-_WHO2004.svg.png)

Neonates are prone to infection in the first month of life. Some organisms such as S. agalactiae (Group B Streptococcus) or (GBS) are more prone to cause these occasionally fatal infections. Risk factors for GBS infection include:

- prematurity (birth before 37 weeks gestation)

- a sibling who has had a GBS infection

- prolonged labour or rupture of membranes

Untreated sexually transmitted infections are associated with congenital and perinatal infections in neonates, particularly in the areas where rates of infection remain high. The overall perinatal mortality rate associated with untreated syphilis, for example, is 30%.[105]

Neonatal death

Infant deaths (neonatal deaths from birth to 28 days, or perinatal deaths if including fetal deaths at 28 weeks gestation and later) are around 1% in modernized countries.

The most important factors affecting mortality in childbirth are adequate nutrition and access to quality medical care ("access" is affected both by the cost of available care, and distance from health services).

A 1983–1989 study by the Texas Department of State Health Services highlighted the differences in neonatal mortality (NMR) between high risk and low risk pregnancies. NMR was 0.57% for doctor-attended high risk births, and 0.19% for low risk births attended by non-nurse midwives. Around 80% of pregnancies are low-risk. Factors that may make a birth high risk include prematurity, high blood pressure, gestational diabetes and a previous cesarean section.

Intrapartum asphyxia

Intrapartum asphyxia is the impairment of the delivery of oxygen to the brain and vital tissues during the progress of labour. This may exist in a pregnancy already impaired by maternal or fetal disease, or may rarely arise de novo in labour. This can be termed fetal distress, but this term may be emotive and misleading. True intrapartum asphyxia is not as common as previously believed, and is usually accompanied by multiple other symptoms during the immediate period after delivery. Monitoring might show up problems during birthing, but the interpretation and use of monitoring devices is complex and prone to misinterpretation. Intrapartum asphyxia can cause long-term impairment, particularly when this results in tissue damage through encephalopathy.[106]

Society and culture

Childbirth routinely occurs in hospitals in much of Western society. Before the 20th century and in some countries to the present day it has more typically occurred at home.[107]

In Western and other cultures, age is reckoned from the date of birth, and sometimes the birthday is celebrated annually. East Asian age reckoning starts newborns at "1", incrementing each Lunar New Year.

Some families view the placenta as a special part of birth, since it has been the child's life support for so many months. The placenta may be eaten by the newborn's family, ceremonially or otherwise (for nutrition; the great majority of animals in fact do this naturally).[108] Most recently there is a category of birth professionals available who will encapsulate placenta for use as placenta medicine by postpartum mothers.

The exact location in which childbirth takes place is an important factor in determining nationality, in particular for birth aboard aircraft and ships.

Facilities

Following are facilities that are particularly intended to house women during childbirth:

- A labour ward, also called a delivery ward or labour and delivery, is generally a department of a hospital that focuses on providing health care to women and their children during childbirth. It is generally closely linked to the hospital's neonatal intensive care unit and/or obstetric surgery unit if present. A maternity ward or maternity unit may include facilities both for childbirth and for postpartum rest and observation of mothers in normal as well as complicated cases.

- A birthing center generally presents a simulated home-like environment. Birthing centers may be located on hospital grounds or "free standing" (i.e., not hospital-affiliated).

In addition, it is possible to have a home birth.

Associated professions

Different categories of birth attendants may provide support and care during pregnancy and childbirth, although there are important differences across categories based on professional training and skills, practice regulations, as well as nature of care delivered.

"Childbirth educators" are instructors who aim to educate pregnant women and their partners about the nature of pregnancy, labour signs and stages, techniques for giving birth, breastfeeding and newborn baby care. In the United States and elsewhere, classes for training as a childbirth educator can be found in hospital settings or through many independent certifying organizations such as Birthing From Within, BirthWorks, The Bradley Method, Birth Arts International, CAPPA, HypBirth, HypnoBabies, HypnoBirthing,[78] ICTC, ICEA, Lamaze, etc. Each organization teaches its own curriculum and each emphasizes different techniques. Information about each can be obtained through their individual websites.

Doulas are assistants who support mothers during pregnancy, labour, birth, and postpartum. They are not medical attendants; rather, they provide emotional support and non-medical pain relief for women during labour. Like childbirth educators and other assistive personnel, certification to become a doula is not compulsory, thus, anyone can call themself a doula or a childbirth educator.

Midwives are autonomous practitioners who provide basic and emergency health care before, during and after pregnancy and childbirth, generally to women with low-risk pregnancies. Midwives are trained to assist during labour and birth, either through direct-entry or nurse-midwifery education programs. Jurisdictions where midwifery is a regulated profession will typically have a registering and disciplinary body for quality control, such as the American Midwifery Certification Board in the United States,[109] the College of Midwives of British Columbia (CMBC) in Canada[110][111] or the Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) in the United Kingdom.[112][113]

In jurisdictions where midwifery is not a regulated profession, traditional or lay midwives may assist women during childbirth, although they do not typically receive formal health care education and training.

Medical doctors who practice obstetrics include categorically specialized obstetricians, family practitioners and general practitioners whose training, skills and practices include obstetrics, and in some contexts general surgeons. These physicians and surgeons variously provide care across the whole spectrum of normal and abnormal births and pathological labour conditions. Categorically specialized obstetricians are qualified surgeons, so they can undertake surgical procedures relating to childbirth. Some family practitioners or general practitioners also perform obstetrical surgery. Obstetrical procedures include cesarean sections, episiotomies, and assisted delivery. Categorical specialists in obstetrics are commonly dually trained in obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN), and may provide other medical and surgical gynecological care, and may incorporate more general, well-woman, primary care elements in their practices. Maternal-fetal medicine specialists are obstetrician/gynecologists subspecialized in managing and treating high-risk pregnancy and delivery.

Anaesthetists or anesthesiologists are medical doctors who specialise in pain relief and the use of drugs to facilitate surgery and other painful procedures. They may contribute to the care of a woman in labour by performing epidurals or by providing anaesthesia (often spinal anaesthesia) for Cesarean section or forceps delivery.

Obstetric nurses assist midwives, doctors, women, and babies before, during, and after the birth process, in the hospital system. Obstetric nurses hold various certifications and typically undergo additional obstetric training in addition to standard nursing training.

Costs

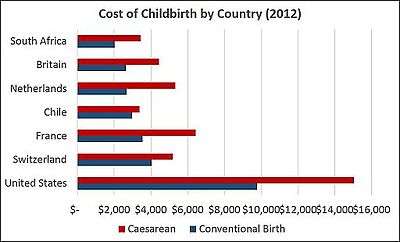

According to a 2013 analysis performed commissioned by the New York Times and performed by Truven Healthcare Analytics, the cost of childbirth varies dramatically by country. In the United States the average amount actually paid by insurance companies or other payers in 2012 averaged $9,775 for an uncomplicated conventional delivery and $15,041 for a caesarean birth.[114] The aggregate charges of healthcare facilities for 4 million annual births in the United States was estimated at over $50 billion. The summed cost of prenatal care, childbirth, and newborn care came to $30,000 for a vaginal delivery and $50,000 for a caesarian section.

In the United States, childbirth hospital stays have some of the lowest ICU utilizations. Vaginal delivery with and without complicating diagnoses and caesarean section with and without comorbidities or major comorbidities account for four of the fifteen types of hospital stays with low rates of ICU utilization (where less than 20% of visits were admitted to the ICU). During stays with ICU services, approximately 20% of costs were attributable to the ICU.[115]

A 2013 study published in BMJ Open found widely varying costs by facility for childbirth expenses in California, varying from $3,296 to $37,227 for vaginal birth and from $8,312 to $70,908 for a caesarean birth.[116]

Beginning in 2014, the United Kingdom National Institute for Health and Care Excellence began recommending that many women give birth at home under the care of a midwife rather than an obstetrician, citing lower expenses and better healthcare outcomes.[117] The median cost associated with home birth was estimated to be about $1,500 vs. about $2,500 in hospital.[118]

See also

- Advanced maternal age, when a woman is of an older age at reproduction

- Antinatalism

- Asynclitic birth, an abnormal birth position

- Bradley method of natural childbirth

- Coffin birth

- Kangaroo care

- Lamaze

- Naegele's Rule to calculate the due date for a pregnancy

- Natalism

- Natural childbirth

- Obstetrical Dilemma

- Pre- and perinatal psychology

- Reproductive Health Supplies Coalition

- Traditional birth attendant

- Unassisted childbirth

- Vernix caseosa

- Water birth

References

- ↑ Martin, Elizabeth. Concise Colour Medical Dictionary. Oxford University Press. p. 375. ISBN 9780199687992.

- ↑ "The World Factbook". www.cia.gov. July 11, 2016. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ↑ "Preterm birth Fact sheet N°363". WHO. November 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2016.

- ↑ Buck, Germaine M.; Platt, Robert W. (2011). Reproductive and perinatal epidemiology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 163. ISBN 9780199857746.

- ↑ Co-Operation, Organisation for Economic; Development (2009). Doing better for children. Paris: OECD. p. 105. ISBN 9789264059344.

- ↑ Olsen, O; Clausen, JA (12 September 2012). "Planned hospital birth versus planned home birth.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (9): CD000352. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000352.pub2. PMC 4238062

. PMID 22972043.

. PMID 22972043. - ↑ Fossard, Esta de; Bailey, Michael (2016). Communication for Behavior Change: Volume lll: Using Entertainment–Education for Distance Education. SAGE Publications India. ISBN 9789351507581. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ Memon, HU; Handa, VL (May 2013). "Vaginal childbirth and pelvic floor disorders.". Women's health (London, England). 9 (3): 265–77; quiz 276–7. doi:10.2217/whe.13.17. PMC 3877300

. PMID 23638782.

. PMID 23638782. - 1 2 "Birth". The Columbia Electronic Encyclopedia (6 ed.). Columbia University Press. 2016. Retrieved 2016-07-30 from Encyclopedia.com. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Pregnancy Labor and Birth". Women's Health. September 27, 2010. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ McDonald, SJ; Middleton, P; Dowswell, T; Morris, PS (11 July 2013). "Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping of term infants on maternal and neonatal outcomes.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 7: CD004074. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004074.pub3. PMID 23843134.

- ↑ Hofmeyr, GJ; Hannah, M; Lawrie, TA (21 July 2015). "Planned caesarean section for term breech delivery.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews (7): CD000166. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000166.pub2. PMID 26196961.

- ↑ Childbirth: Labour, Delivery and Immediate Postpartum Care. World Health Organization. 2015. p. Chapter D. ISBN 978-92-4-154935-6. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ↑ Molina, G; Weiser, TG; Lipsitz, SR; Esquivel, MM; Uribe-Leitz, T; Azad, T; Shah, N; Semrau, K; Berry, WR; Gawande, AA; Haynes, AB (1 December 2015). "Relationship Between Cesarean Delivery Rate and Maternal and Neonatal Mortality". JAMA. 314 (21): 2263–70. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.15553. PMID 26624825.

- 1 2 3 4 Education material for teachers of midwifery : midwifery education modules (PDF) (2nd ed.). Geneva [Switzerland]: World Health Organisation. 2008. p. 3. ISBN 978-92-4-154666-9.

- ↑ Martin, Richard J.; Fanaroff, Avroy A.; Walsh, Michele C. Fanaroff and Martin's Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine: Diseases of the Fetus and Infant. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 116. ISBN 9780323295376.

- ↑ Weber, S.E. (1996). "Cultural aspects of pain in childbearing women". Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 25 (1): 67–72. doi:10.1111/j.1552-6909.1996.tb02515.x. PMID 8627405.

- ↑ Callister, L.C.; Khalaf, I.; Semenic, S.; Kartchner, R.; et al. (2003). "The pain of childbirth: perceptions of culturally diverse women". Pain Management Nursing. 4 (4): 145–54. doi:10.1016/S1524-9042(03)00028-6. PMID 14663792.

- ↑ Hodnett, E.D. (2002). "Pain and women's satisfaction with the experience of childbirth: A systematic review". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 186 (5 (Supplement)): S160–72. doi:10.1016/S0002-9378(02)70189-0. PMID 12011880.

- ↑ Harms, Rogert W. Does back labor really happen?, mayoclinic.com, Retrieved 8 September 2014

- ↑ Meyer, D. (2007). "Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and their effects on relationship satisfaction". The Family Journal. 15 (4): 392–397. doi:10.1177/1066480707305470.

- ↑ Bowen, R. (July 12, 2010). "Oxytocin". Hypertexts for Biomedical Sciences. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ Zlotnick, C.; Johnson, S.L.; Miller, I.W.; Pearlstein, T.; et al. (2001). "Postpartum depression in women receiving public assistance: Pilot study of an interpersonal-therapy-oriented group intervention". American Journal of Psychiatry. 158 (4): 638–40. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.158.4.638. PMID 11282702.

- ↑ Chabrol, H.; Teissedre, F.; Saint-Jean, M.; Teisseyre, N.; Sistac, C.; Michaud, C.; Roge, B. (2002). "Detection, prevention and treatment of postpartum depression: A controlled study of 859 patients". L'Encephale. 28 (1): 65–70. PMID 11963345.

- ↑ Pillitteri, A. (2010). "Chapter 15: Nursing Care of a Family During Labor and Birth". Maternal & Child Health Nursing: Care of the Childbearing & Childrearing Family. Hagerstown, Maryland: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 350. ISBN 978-1-58255-999-5. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ Healthline Staff; Levine, D. (Medical Reviewer) (March 15, 2012). "Types of Forceps Used in Delivery". Healthline. Healthline Networks. Retrieved 2013-08-10.

- ↑ Kupferminc, M.; Lessing, J. B.; Yaron, Y.; Peyser, M. R. (1993). "Nifedipine versus ritodrine for suppression of preterm labour". BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 100 (12): 1090–1094. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.1993.tb15171.x.

- ↑ Jokic, M.; Guillois, B.; Cauquelin, B.; Giroux, J. D.; Bessis, J. L.; Morello, R.; Levy, G.; Ballet, J. J. (2000). "Fetal distress increases interleukin-6 and interleukin-8 and decreases tumour necrosis factor-alpha cord blood levels in noninfected full-term neonates". BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 107 (3): 420–425. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13241.x.

- ↑ Lyrenas, S.; Clason, I.; Ulmsten, U. (2001). "In vivo controlled release of PGE2 from a vaginal insert (0.8 mm, 10 mg) during induction of labour". BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 108 (2): 169–178. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2001.00039.x.

- ↑ Giacalone, P. L.; Vignal, J.; Daures, J. P.; Boulot, P.; Hedon, B.; Laffargue, F. (2000). "A randomised evaluation of two techniques of management of the third stage of labour in women at low risk of postpartum haemorrhage". BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 107 (3): 396–400. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2000.tb13236.x.

- ↑ Hantoushzadeh, S.; Alhusseini, N.; Lebaschi, A. H. (2007). "The effects of acupuncture during labour on nulliparous women: A randomised controlled trial". The Australian and New Zealand Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 47 (1): 26–30. doi:10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00674.x. PMID 17261096.

- ↑ Reiter, R. J.; Tan, D. X.; Korkmaz, A.; Rosales-Corral, S. A. (2013). "Melatonin and stable circadian rhythms optimize maternal, placental and fetal physiology". Human Reproduction Update. 20 (2): 293–307. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt054. ISSN 1355-4786. PMID 24132226.

- ↑ Usatine, R.P. (developer). "Labor & Delivery". Maternity Guide (for medical residents). Family & Community Medicine Dept, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ Satin, A.J. (July 1, 2013). "Latent phase of labor". UpToDate. Wolters Kluwer.(subscription required)

- ↑ Murray, L.J.; Hennen, L.; Scott, J. (2005). The BabyCenter Essential Guide to Pregnancy and Birth: Expert Advice and Real-World Wisdom from the Top Pregnancy and Parenting Resource. Emmaus, Pennsylvania: Rodale Books. pp. 294–295. ISBN 1-59486-211-7. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ Young, Roger (2016). "Mechanotransduction mechanisms for coordinating uterine contractions in human labor.". Reproduction. 152: R51–R61. doi:10.1530/REP-16-0156.

- ↑ Obstetric Data Definitions Issues and Rationale for Change, 2012 by ACOG.

- ↑ Boyle A, Reddy UM, Landy HJ, Huang CC, Driggers RW, Laughon SK (Jul 2013). "Primary cesarean delivery in the United States.". Obstetrics and gynecology. 122 (1): 33–40. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3182952242. PMC 3713634

. PMID 23743454.

. PMID 23743454. - ↑ Su, M.; Hannah, W. J.; Willan, A.; Ross, S.; Hannah, M. E. (2004). "Planned caesarean section decreases the risk of adverse perinatal outcome due to both labour and delivery complications in the Term Breech Trial". BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 111 (10): 1065–74. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2004.00266.x. PMID 15383108.

- ↑ Sjukvårdsrådgivningen (In Swedish) - Official information of the County Councils of Sweden. Last updated: 2013-01-16. Reviewer: Roland Boij, gynecologist and obstetrician

- ↑ BabyCentre Medical Advisory Board (September 2012). "Speeding up labour". BabyCentre. Johnson & Johnson. Retrieved 2013-08-18.

- ↑ Zhang, J.; Troendle, J.F.; Yancey, M.K. (2002). "Reassessing the labor curve in nulliparous women". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 187 (4): 824–8. doi:10.1067/mob.2002.127142. PMID 12388957.

- ↑ Peisner, D.B.; Rosen, M.G. (1986). "Transition from latent to active labor". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 68 (4): 448–51. PMID 3748488.

- ↑ Rouse, D.J.; Weiner, S.J.; Bloom, S.L.; Varner, M.W.; et al. (2009). "Second-stage labour duration in nulliparous women: Relationship to maternal and perinatal outcomes". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 201 (4): 357.e1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2009.08.003. PMC 2768280

. PMID 19788967.

. PMID 19788967. - ↑ Jangsten, E.; Mattsson, L.; Lyckestam, I.; Hellström, A.; et al. (2011). "A comparison of active management and expectant management of the third stage of labour: A Swedish randomised controlled trial". BJOG: an International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 118 (3): 362–9. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0528.2010.02800.x. PMID 21134105.

- ↑ Weeks, A.D. (2008). "The retained placenta". Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 22 (6): 1103–17. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2008.07.005. PMID 18793876.

- ↑ Ball, H. (June 2009). "Active management of the third state of labor is rare in some developing countries". International Perspectives on Sexual and Reproductive Health. 35 (2).

- ↑ Stanton, C.; Armbruster, D; Knight, R.; Ariawan, I.; et al. (February 13, 2009). "Use of active management of the third stage of labour in seven developing countries". Bulletin of the World Health Organization. 87 (3): 207–13. doi:10.2471/BLT.08.052597. PMC 2654655

. PMID 19377717.

. PMID 19377717. - ↑ International Confederation of Midwives; International Federation of Gynaecologists Obstetricians (2004). "Joint statement: Management of the third stage of labour to prevent post-partum haemorrhage". Journal of Midwifery & Women's Health. 49 (1): 76–7. doi:10.1016/j.jmwh.2003.11.005. PMID 14710151.

- ↑ Mathai, M.; Gülmezoglu, A.M.; Hill, S. (2007). "WHO recommendations for the prevention of postpartum haemorrhage" (PDF). Geneva: World Health Organization, Department of Making Pregnancy Safer. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-07-05.

- ↑ McDonald, SJ; Middleton, P; Dowswell, T; Morris, PS (Jul 11, 2013). McDonald, Susan J, ed. "Effect of timing of umbilical cord clamping of term infants on maternal and neonatal outcomes". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 7: CD004074. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004074.pub3. PMID 23843134.

- ↑ Gjerdingen, D.K.; Froberg, D.G. (1991). "The fourth stage of labor: The health of birth mothers and adoptive mothers at six-weeks postpartum". Family medicine. 23 (1): 29–35. PMID 2001778.

- 1 2 WHO (2013). "WHO recommendations on postnatal care of the mother and newborn". World Health Organization. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ↑ "Postpartum Assessment". ATI Nursing Education. Retrieved 24 December 2014.

- ↑ Mayo clinic staff. "Postpartum care: What to expect after a vaginal delivery". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Saloojee, H. (4 January 2008). "Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants". The WHO Reproductive Health Library. WHO. Retrieved 23 December 2014.

- ↑ Crenshaw, Jennette (2007). "Care Practice #6: No Separation of Mother and Baby, With Unlimited Opportunities for Breastfeeding". J Perinat Educ. 16: 39–43. doi:10.1624/105812407X217147. PMC 1948089

. PMID 18566647.

. PMID 18566647. - ↑ Moore, Elizabeth; Anderson, Gene; Bergnam, Nils; Dowswell, Therese (16 May 2012). "Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 5: CD003519. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003519.pub3. PMC 3979156

. PMID 22592691.

. PMID 22592691. - ↑ Moore ER, Anderson GC, Bergman N (2007). "Early skin-to-skin contact for mothers and their healthy newborn infants (Review)" (PDF). The Cochrane Collaboration. Retrieved 22 December 2014.

- ↑ Phillips, Raylene. "Uninterrupted Skin-to-Skin Contact Immediately After Birth". Medscape. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ↑ "Essential Antenatal, Perinatal and Postpartum Care" (PDF). Promoting Effective Perinatal Care. WHO. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ↑ "Care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth". National Collaborating Centre for Women's and Children's Health. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. December 2014. Archived from the original on 12 February 2015. Retrieved 21 December 2014.

- ↑ National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (December 2014). "Intrapartum care: care of healthy women and their babies during childbirth". http://www.nice.org.uk/. Retrieved 11 February 2015. External link in

|website=(help) - ↑ Tranmer, J.E.; Hodnett, E.D.; Hannah, M.E.; Stevens, B.J. (2005). "The effect of unrestricted oral carbohydrate intake on labor progress". Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing. 34 (3): 319–26. doi:10.1177/0884217505276155. PMID 15890830.

- ↑ O'Sullivan, G.; Scrutton, M. (2003). "NPO during labor. Is there any scientific validation?". Anesthesiology Clinics of North America. 21 (1): 87–98. doi:10.1016/S0889-8537(02)00029-9. PMID 12698834.

- ↑ Singata, M.; Tranmer, J.; Gyte, G.M.L. (2013). Singata, Mandisa, ed. Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. "Restricting oral fluid and food intake during labour". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. Cochrane Collaboration. CD003930 (8): CD003930. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003930.pub3. PMID 23966209. Lay summary – Cochrane Summaries (2013-08-22).

- ↑ Basevi, V.; Lavender, T. (2001). Basevi, Vittorio, ed. Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. "Routine perineal shaving on admission in labour". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. CD001236 (1): CD001236. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD001236. PMID 11279711. Lay summary – Cochrane Summaries (2009-04-15).

- ↑ Lumbiganon, P; Thinkhamrop, J; Thinkhamrop, B; Tolosa, JE (Sep 14, 2014). "Vaginal chlorhexidine during labour for preventing maternal and neonatal infections (excluding Group B Streptococcal and HIV).". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 9: CD004070. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004070.pub3. PMID 25218725.

- ↑ Haas, DM; Morgan, S; Contreras, K (21 December 2014). "Vaginal preparation with antiseptic solution before cesarean section for preventing postoperative infections.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 12: CD007892. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007892.pub5. PMID 25528419.

- ↑ Brown, Heather; Paranjothy S; Dowswell T; Thomas J (September 2013). Brown, Heather C, ed. "Package of care for active management in labour for reducing caesarean section rates in low-risk women". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (9). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD004907.pub3.

- 1 2 "Rates for total cesarean section, primary cesarean section, and vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC), United States, 1989–2010" (PDF). Childbirth Connection website. Relentless Rise in Cesarian Rate. August 2012. Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- ↑ "Your Options for Maternity Services".

- 1 2 3 4 5 Main, E.; Oshiro, B.; Chagolla, B.; Bingham, D.; et al. (July 2010). "Elimination of Non-medically Indicated (Elective) Deliveries Before 39 Weeks Gestational Age (California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative Toolkit to Transform Maternity Care)" (PDF). Developed under contract #08-85012 with the California Department of Public Health; Maternal, Child and Adolescent Health Division. (1st ed.). March of Dimes. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2012-11-20. Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- 1 2 "Induction of Labor" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-07-12.

- ↑ Hamilton, B.E.; Martin, J.A.; Ventura, S.J. (March 18, 2009). "Births: Preliminary data for 2007" (PDF). National Vital Statistics Reports. National Vital Statistics System, National Center for Health Statistics, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, US Department of Health and Human Services. 57 (12): 1–22. Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- ↑ Mozurkewich, E.L.; Chilimigras, J.L.; Berman, D.R.; Perni, U.C.; et al. (October 27, 2011). "Methods of induction of labor: A systematic review". BMC Pregnancy & Childbirth. 11: 84. doi:10.1186/1471-2393-11-84. PMC 3224350

. PMID 22032440.

. PMID 22032440. - ↑ ACOG District II Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Committee (December 2011). "Oxytocin for Induction" (PDF). Optimizing Protocols in Obstetrics. Series 1. American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG). Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- 1 2 Graves, Katharine (2012). The HypnoBirthing Book - An inspirational guide for a calm, confident, natural birth. ISBN 978-0-9571445-0-7.

- ↑ Jones L, Othman M, Dowswell T, Alfirevic Z, Gates S, Newburn M, Jordan S, Lavender T, Neilson JP (2012). "Pain management for women in labour: an overview of systematic reviews". Reviews. Wiley Online Library. 3: CD009234. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009234.pub2. PMID 22419342. Retrieved 27 December 2014.

- ↑ "Immersion in Water During Labor and Delivery". Pediatrics. 133 (4): 758–761. 20 March 2014. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-3794.

- 1 2 Hodnett, E.D.; Gates, S.; Hofmeyr, G.J.; Sakala, C. (2013). Hodnett, Ellen D, ed. Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. "Continuous support for women during childbirth". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. CD003766 (7): CD003766. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003766.pub5. PMID 23857334. Lay summary – Cochrane Summaries (2013-07-15).

- ↑ "Safe Prevention of the Primary Cesarean Delivery". American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (the College) and the Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. March 2014. Retrieved 20 February 2014.

- ↑ Derry, S.; Straube, S.; Moore, RA.; Hancock, H.; Collins, SL. (2012). Derry, Sheena, ed. "Intracutaneous or subcutaneous sterile water injection compared with blinded controls for pain management in labour". Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 1: CD009107. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009107.pub2. PMID 22258999.

- ↑ Thorp, J.A.; Breedlove, G. (1996). "Epidural analgesia in labor: An evaluation of risks and benefits". Birth. 23 (2): 63–83. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.1996.tb00833.x. PMID 8826170.

- ↑ Alehagen, S.; Wijma, B.; Lundberg, U.; Wijma, K. (September 2005). "Fear, pain and stress hormones during childbirth". Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology. 26 (3): 153–65. doi:10.1080/01443610400023072. PMID 16295513.

- ↑ Loftus, J.R.; Hill, H.; Cohen, S.E. (August 1995). "Placental transfer and neonatal effects of epidural sufentanil and fentanyl administered with bupivacaine during labor". Anesthesiology. 83 (2): 300–8. doi:10.1097/00000542-199508000-00010. PMID 7631952.

- ↑ Anim-Somuah, M.; Smyth, R.M.; Jones, L. (2011). Anim-Somuah, Millicent, ed. Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. "Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. CD000331 (12): CD000331. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000331.pub3. PMID 22161362. Lay summary – Cochrane Summaries (2011-12-07).

- ↑ Wei, S.Q.; Luo, Z.C.; Xu, H.; Fraser, W.D. (September 2009). "The effect of early oxytocin augmentation in labour: A meta-analysis". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 114 (3): 641–9. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b11cb8. PMID 19701046.

- 1 2 Rohwer, Anke; Kondowe O; Young T (2013). "Antispasmodics for labour". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 6 (6): CD009243. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009243.pub3. PMID 23737030.

- ↑ Carroli, G.; Mignini, L. (2009). Carroli, Guillermo, ed. Pregnancy and Childbirth Group. "Episiotomy for vaginal birth". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. CD000081 (1): CD000081. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000081.pub2. PMID 19160176. Lay summary – Cochrane Summaries (2012-11-14).

- ↑ Leavitt, Judith W. (1988). Brought to Bed: Childbearing in America, 1750–1950. University of Oxford. pp. 90–91. ISBN 978-0-19-505690-7.

- ↑ Vernon, D. "Men At Birth – Should Your Bloke Be There?". BellyBelly.com.au. Retrieved 2013-08-23.

- ↑ Hammond, P.; Johnson, A. (1986). "Tocodynamometer". In Brown, M. The Medical Equipment Dictionary. London: Chapman & Hall. ISBN 0-412-28290-9. Retrieved 2013-08-23. Online version accessed.

- 1 2 Dziadosz, M; Basch, RS; Young, BK (March 2016). "Human amniotic fluid: a source of stem cells for possible therapeutic use.". American journal of obstetrics and gynecology. 214 (3): 321–7. PMID 26767797.

- 1 2 "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2004" (xls). Department of Measurement and Health Information, World Health Organization.

- 1 2 Van Lerberghe, W.; De Brouwere, V. (2001). "Of Blind Alleys and Things That Have Worked: History's Lessons on Reducing Maternal Mortality" (PDF). In De Brouwere, V.; Van Lerberghe, W. Safe Motherhood Strategies: A Review of the Evidence. Studies in Health Services Organisation and Policy. 17. Antwerp: ITG Press. pp. 7–33. ISBN 90-76070-19-9.

Where nothing effective is done to avert maternal death, "natural" mortality is probably of the order of magnitude of 1,500/100,000.

- ↑ Levi, J.; Kohn, D.; Johnson, K. (June 2011). "Healthy Women, Healthy Babies: How health reform can improve the health of women and babies in America" (PDF). Washington, D.C.: Trust for America's Health. Retrieved 2013-08-29.

- ↑ Bates, E.; Rouse, D.J.; Mann, M.L.; Chapman, V.; et al. (December 2010). "Neonatal outcomes after demonstrated fetal lung maturity before 39 weeks of gestation". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 116 (6): 1288–95. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181fb7ece. PMC 4074509

. PMID 21099593.

. PMID 21099593. - ↑ Education material for teachers of midwifery : midwifery education modules (PDF) (2nd ed.). Geneva [Switzerland]: World Health Organisation. 2008. pp. 17–36. ISBN 978-92-4-154666-9.

- ↑ Buppasiri, P; Lumbiganon, P; Thinkhamrop, J; Thinkhamrop, B (Oct 7, 2014). "Antibiotic prophylaxis for third- and fourth-degree perineal tear during vaginal birth.". The Cochrane database of systematic reviews. 10: CD005125. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005125.pub4. PMID 25289960.

- ↑ Say, L.; Inoue, M.; Mills, S.; Suzuki, E. (2008). Maternal Mortality in 2005 : Estimates Developed by WHO, UNICEF, UNFPA and The World Bank (PDF). Geneva: Reproductive Health and Research, World Health Organization. ISBN 978-92-4-159621-3.

- ↑ "Maternal mortality ratio falling too slowly to meet goal" (Joint press release). World Health Organization; UNICEF; United Nations Population Fund; World Bank. October 12, 2007. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ↑ Warwick, R.; Williams, P.L., eds. (1973). Gray's Anatomy (35th British ed.). London: Longman. p. 1046. ISBN 978-0-443-01011-8.

- ↑ "Mortality and Burden of Disease Estimates for WHO Member States in 2004" (xls). Department of Measurement and Health Information, World Health Organization. February 2009.

- ↑ "Sexually transmitted infections (STIs)". World Health Organization. May 2013. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ↑ Handel, M.; Swaab, H.; De Vries, L.S.; Jongmans, M.J. (2007). "Long-term cognitive and behavioral consequences of neonatal encephalopathy following perinatal asphyxia: A review". European Journal of Pediatrics. 166 (7): 645–54. doi:10.1007/s00431-007-0437-8. PMC 1914268

. PMID 17426984.

. PMID 17426984. - ↑ Stearns, P.N., ed. (1993-12-21). Encyclopedia of Social History. Garland Reference Library of Social Sciences. V. 780. London: Taylor & Francis. p. 144. ISBN 978-0-8153-0342-8.

- ↑ Vernon, D.M.J., ed. (2005). Having a Great Birth in Australia: Twenty Stories of Triumph, Power, Love and Delight from the Women and Men who Brought New Life Into the World. Canberra, Australia: Australian College of Midwives. p. 56. ISBN 978-0-9751674-3-4.

- ↑ http://www.amcbmidwife.org/about-amcb

- ↑ "Welcome to the College of Midwives of British Columbia". College of Midwives of British Columbia website. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ↑ Province of British Columbia (August 21, 2013) [Revised Statues of British Columbia 1996]. "Health Professions Act". Statues and Regulations of British Columbia internet version. Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada: Queens Printer. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ↑ "Our role". Nursing & Midwifery Council website. London, England. 2011-08-31 [Created 2010-02-24]. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ↑ "The Nursing and Midwifery Order 2001". London, England: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, The National Archives, Ministry of Justice, Her Majesty's Government. 2002.

- 1 2 "American Way of Birth, Costliest in the World - NYTimes.com".

- ↑ Barrett ML, Smith MW, Elizhauser A, Honigman LS, Pines JM (December 2014). "Utilization of Intensive Care Services, 2011". HCUP Statistical Brief #185. Rockville, MD: Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality.

- ↑ Hsia, RY; Akosa Antwi, Y; Weber, E (2014). "Analysis of variation in charges and prices paid for vaginal and caesarean section births: a cross-sectional study". BMJ Open. 4 (1): e004017. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004017. PMC 3902513

. PMID 24435892.

. PMID 24435892.

- ↑ "www.nice.org.uk". Archived from the original on 2015-02-12.

- ↑ "British Regulator Urges Home Births Over Hospitals for Uncomplicated Pregnancies - NYTimes.com".

External links

| Wikinews has related news: 17-pound baby born in Russia |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Childbirth. |