Paula Rego

| Paula Rego | |

|---|---|

| Born |

26 January 1935 Portugal |

| Nationality | Portuguese |

| Known for | Painting, printmaking |

| Spouse(s) | Victor Willing |

| Awards | Grã-Cruz da Ordem Militar de Sant'Iago da Espada |

Dame Paula Rego, DBE (born 26 January 1935), is a Portuguese-born visual artist who is particularly known for her paintings and prints based on storybooks.[1] Rego’s style has evolved from abstract towards representational, and she has favoured pastels over oils for much of her career. Her work often reflects feminism, coloured by folk-themes from her native Portugal.

Rego studied at the Slade School of Fine Art and was an exhibiting member of the London Group, along with David Hockney and Frank Auerbach.[2] She was the first artist-in-residence at the National Gallery in London.[3] She lives and works in London.[4]

Biography

Early life

Rego was born on 26 January 1935 in Lisbon, Portugal.[5] Her father was an electrical engineer who worked for the Marconi Company.[3] Although this gave her a comfortable middle-class home, the family was divided in 1936 when her father was posted to work in the United Kingdom. Rego's parents left her behind in Portugal in the care of her grandmother until 1939. Rego's grandmother was to become a significant figure in her life, as she learned from her grandmother and the family maid many of the traditional folktales that would one day make their way into her art work.[6]

Rego's family were keen Anglophiles, and Rego was sent to the only English-language school in Portugal at the time, Saint Julian's School in Carcavelos, which she attended from 1945 to 1951.[5] Although nominally a Catholic and living in a devoutly Catholic country, St Julian's School was Anglican and this combined with the hostility of Rego's father to the Catholic Church served to create a distance between her and full-blooded Catholic belief. Rego has described herself as having become a "sort of Catholic", but as a child she possessed a sense of Catholic guilt and a very strong belief that the Devil was real.[7]

In 1951, Rego was sent to the United Kingdom to attend a finishing school called The Grove School, in Sevenoaks, Kent. Unhappy there, Rego attempted in 1952 to start studies in art at the Chelsea School of Art in London, but was advised against this choice by her legal guardian in Britain, David Phillips, who had heard that a young woman had become pregnant while a student there. He suggested to her parents that The Slade School of Fine Art was a more respectable choice and helped her achieve a place there. She attended the Slade School from 1952 to 1956.[4]

At the Slade, Rego had met her future husband, Victor Willing, who was also a student there.[5] In 1957, Rego and Willing left London to live in Ericeira, Portugal.[5] They were able to marry in 1959 following Willing's divorce from his first wife, Hazel Whittington.[8] Three years later Rego's father bought the couple a house in London, at Albert Street in Camden Town, and Rego's time was spent divided between Britain and Portugal.

In 1966, Rego's father died, and the family electrical business was taken over, unwillingly, by Rego's husband, although he had himself been diagnosed with multiple sclerosis.[6] The company failed in 1974 during the Portuguese revolution that overthrew the country's right-wing Estado Novo dictatorship, when its production works were taken over by revolutionary forces, even though Rego's family had been supporters of the political Left. As a result, Rego, Willing and their children moved permanently to London and spent most of their time there until Willing's death in 1988.[9]

Career

Although Rego was commissioned by her father to produce a series of large-scale murals to decorate the works' canteen at his electrical factory in 1954, while she was still a student, Rego's artistic career effectively began in early 1962, when she began exhibiting with The London Group, a long-established artists' organization which had David Hockney and Frank Auerbach among its members. In 1965, she was selected to take part in a group show, Six Artists, at the Institute of Contemporary Arts, ICA, in London.[10] That same year she had her first solo show at the Sociedade Nacional de Belas Artes (SNBA) in Lisbon.[6] She was also the Portuguese representative at the 1969 São Paulo Art Biennial.[11] Between 1971 and 1978 she had seven solo shows in Portugal, in Lisbon and Oporto, and then a series of solo exhibitions in Britain, including at the AIR Gallery in London in 1981, the Arnolfini in Bristol in 1983, and the Edward Totah Gallery in London in 1984, 1985 and 1987.[12]

In 1988, Rego was the subject of a retrospective exhibition at the Calouste Gulbenkian Foundation in Lisbon and the Serpentine Gallery in London.[13] This led to her being invited to become the first Associate Artist at the National Gallery, London in 1990, in what was the first of a series of artist-in-residence schemes organized by the gallery.[14] From this emerged two sets of work. The first was a series of paintings and prints on the theme of nursery rhymes, which was taken around Britain and elsewhere by the Arts Council of Great Britain and the British Council from 1991 to 1996. The second was a series of large-scale paintings inspired by the paintings of Carlo Crivelli in the National Gallery, known as Crivelli’s Garden which is now housed in the main restaurant at the gallery.

Other exhibitions include a retrospective at Tate Liverpool in 1997, Dulwich Picture Gallery in 1998, Tate Britain in 2005, and Birmingham Museum and Art Gallery in 2007. A major retrospective of her work was held at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia in Madrid in 2007, which travelled to the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington, D.C. the following year.

In 2008, Rego exhibited at the Marlborough Chelsea in New York, and staged a retrospective of her graphic works at the Ecole Superieure des Beaux-Arts in Nimes, France. As well as showing at Marlborough Fine Art in London in 2010, the art critic Marco Livingstone organised a retrospective of her work at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Monterrey, Mexico, which was later shown at the Pinacoteca de São Paulo in Brazil.

Rego's art work can be seen in many public and private institutions around the world. The artist has 43 works in the collection of the British Council, ten works in the collection of the Arts Council of England, and 46 works at the Tate Gallery, London.

Rego is currently represented by Marlborough Fine Art.[15]

Style and influences

Rego is a prolific painter and printmaker, and in earlier years also produced collage work.[16] Her well-known depictions of folk tales and images of young girls, made largely since 1990, bring together methods of painting and printmaking that emphasise strong, clearly drawn forms, in contrast to the looser style of her earlier paintings.

In her earliest works, such as Always at Your Excellency's Service, painted in 1961, Rego was strongly influenced by Surrealism, and particularly the work of Joan Miró.[17] This shows itself not only in the type of imagery that appears in these works, but in the method employed, which is based on the Surrealist idea of automatic drawing, in which the artist attempts to disengage the conscious mind from the making process in order to allow the unconscious mind to direct the making of an image.[18] At times these paintings almost verge on abstraction; however, as exemplified by Salazar Vomiting the Homeland, painted in 1960, when Portugal's right-wing dictator Salazar was in power, even when her work veered toward abstraction, a strong narrative element remains in place.[19]

There are two principal reasons why Rego adopted a semi-abstract style in the 1960s. First, abstraction dominated in avant-garde artistic circles at the time, which had set figurative art on the defensive. But Rego was also reacting against her training at the Slade School of Art, where a very strong emphasis had been placed on anatomical figure drawing. Under the encouragement of her fellow student and later husband Victor Willing, Rego kept alongside her official school sketchbooks a "secret sketchbook" when she was at the Slade, in which she made free-form drawings of a type that would have been frowned upon by her tutors.[20] Rego's apparent dislike of crisp drawing techniques in the 1960s shows itself not only in the style of such works as Faust and her Red Monkey series of the 1980s, which resemble expressionistic comic-book drawing, but in her acknowledged influences at the time, which included Jean Dubuffet and Chaim Soutine.[21]

A notable change in Rego's style emerged in 1990, following her appointment as the first Associate Artist of the National Gallery in London, under what was effectively an artist-in-residence scheme. The remit of the Associate Artist is to "make new work that in some way connects to the National Gallery Collection." [22] The National Gallery is overwhelmingly an Old Masters collection and Rego seems to have been pulled back towards a much clearer, or tighter, linear style reminiscent of the highly-wrought drawing technique that she was taught at the Slade. The result was a series of works which came to characterise the popular perception of Rego's style, combining strong clear drawing with depictions of equally strong women in sometimes disturbing situations. Works such as Crivelli's Garden have clear links to the paintings by Carlo Crivelli in the National Gallery, but other works made at the time, such as Joseph's Dream and The Fitting, draw from works by Old Masters such as Diego Velázquez, in terms of subject matter and spatial representation.[23]

Rego gave up working with collage in the late 1970s, and began using pastels as a medium in the early 90s. She continues to use pastels to this day, almost to the exclusion of oil paint.[24] Among the most notable works made in pastel are in her Dog Women series, in which women are shown sitting, squatting, scratching and generally behaving as if they were dogs. This antithesis of what is considered feminine behaviour, and many of her other works in which there appears to be either the threat of female violence or its actual manifestation, have caused Rego to be associated with feminism. She has acknowledged reading at a young age Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex, a key feminist text, and that this made a deep impression on her.[25] Her work also seems to chime with the interest in Freudian criticism shown by feminist writers on art in the 1990s, such as Griselda Pollock, with works such as Girl Lifting up her Skirt to a Dog of 1986 and Two Girls and a Dog of 1987 appearing to have disturbing sexual undertones.[26] However, Rego has been known to rebuke critics who read too much sexual content into her work.[24] Another explanation for Rego's depiction of women as unfeminine, animalistic or brutal beings is that this reflects the physical reality of women as human beings in the physical world, rather than the idealised female type in the minds of men.[27]

Solo exhibitions

- Sociedade Nacional de Belas-Artes, Lisbon (1965)[28]

- Galeria São Mamede, Lisbon (1971)[28]

- Galeria Alvarez, Oporto (1972)[28]

- Galeria da Emenda, Lisbon (1974)[28]

- Módulo Centro Difusor da Arte, Lisbon (1975)[28]

- Módulo Centro Difusor da Arte, Oporto (1977)[28]

- Galeria III, Lisbon (1978)[28]

- AIR Gallery, London (1981)[28]

- Galeria III, Lisbon (1982)[28]

- Edward Totah Gallery, London (1982)[28]

- Arnolfini, Bristol (1983)[28]

- Galerie Espace, Amsterdam (1983)[28]

- South Hill Park Arts Centre, Nottingham, England (1984)[28]

- Edward Totah Gallery, London (1984)[28]

- The Art Palace, New York (1985)[28]

- Edward Totah Gallery, London (1985)[28]

- Selected work 1981‑1986, Aberystwyth Arts Centre (1987)[28]

- Retrospective Exhibition, Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon (1988)[28]

- Serpentine Gallery, London (1988)[28]

- Nursery Rhymes, Marlborough Graphics Gallery, Galeria III and Galeria Zen (1989)[28]

- Tales from the National Gallery, National Gallery, London (1991)[28]

- Peter Pan & Other Stories, Marlborough Fine Art, London (1992)[28]

- Nursery Rhymes, Cheltenham Literary Festival (1993)[28]

- Dog Women, Marlborough Fine Art, London (1994)[28]

- Nursery Rhymes, Cardiff Literature Festival (1995)[28]

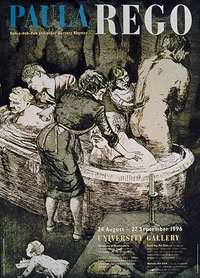

- Nursery Rhymes, University Gallery, University of Northumbria at Newcastle (1996)[28]

- Paula Rego, Tate Gallery Liverpool (1997)[29]

- Pendle Witches and Peter Pan, Midland Art Centre (1998)[28]

- The Sins of Father Amaro, Dulwich Picture Gallery, London (1998)[30]

- Pra Lá et Pra Cá, Galerie III, Lisbon (1998) [28]

- The Children's Crusade, Marlborough Graphics, London (1999)[28]

- Open Secrets – Drawings and Etchings by Paula Rego, University Art Gallery, University of Massachusetts, USA (1999)[28]

- Celestina’s House, Abbot Hall Art Gallery and the Yale Center for British Art (2001)[28]

- Jane Eyre, Marlborough Gallery Inc. (2002)[28]

- Corner 2004, Charlottenborg, Copenhagen (2003)[28]

- Paula Rego in Focus, Tate Britain (2004)[31]

- Paula Rego, Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía (2007) [32]

Bibliography

Exhibition catalogues

- Il Exposiçao de Artes Plasticas, Fundaçao Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon (1961).[4]

- Paula Rego, Fundaçao Calouste Gulbenkian, Lisbon, (1961).[4]

- de Lacerda, Alberto. Fragmentos de um poema intitulado Paula Rego, Paula Rego, SNBA, LisbonVictor Willing: Six Artists, Institute of Contemporary Art, London, (1965).[4]

- Art Portugais - Peinture et Sculpture de Naturalisme à nos jours, Brussels, (1967).[4]

- Paula Rego Expoé, Galeria São Mameda, Lisbon, (1971).[4]

- Esposiçao Colectiva, Galeria Sâo Mamede, Lisbon, (1972).[4]

- Salette Taveres: A Estrutura Semântica na obra de Paula Rego, Expo AICA, SNBA, (1974).[4]

- Wohl, Helmut. Portuguese Art since 1910, Royal Academy of Art, London, (1978).[4]

- Willing, Victor. Paula Rego: Paintings 1982 - 3 Arnolfini, Bristol; Galerie Espace, Amsterdam, (1983).[4]

- Petherbridge, Deana. Nineteen Eighty-Four in 1984, Camden Arts Centre, London, (1984).[4]

- Cooke, Lynne. Paula Rego: Paintings 1984 - 5 Edward Totah (1985).[4]

- Moffat, Alexander. Retrieving the Image, The British Art Show, Arts Council of Great Britain, (1985).[4]

- Hicks, Alistair. Paula Rego: Selected Work 1981 - 1986, Aberystwyth Arts Centre, (1986).[4]

- Nine Portuguese Painters, John Hansard Gallery, Southampton, (1986).[4]

- 70 - 80 Arte Portuguesa, Brazil, São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, (1987).[4]

- Biggs, Lewis and Elliott, David, Current Affairs, Museum of Modern Art, Oxford; Feira do Circo, Forum Picoas, Lisbon, (1987).[4]

- Works on paper by contemporary artists, Marlborough Fine Art, London (1988).[4]

- Warner, Marina. Essay in Nursery Rhymes, Marlborough Graphics Gallery, London, (1989).[4]

- McEwen, John. Paula Rego The Nursery Rhymes, South Bank Centre Touring Exhibition (1990).[4]

- Patrick, Keith. Maité Lores: From Bacon to Now ‑ The Outsider in British Figuration, Palazzo Vecchio, Florence, (1991).[4]

- Greer, Germaine and Wiggins, Colin. Essays for Tales from the National Gallery, National Gallery, London, (1991).[4]

- Petherbridge, Deanna. The Primacy of Drawing - An Artist's View, South Bank, (1991).[4]

- Peter Pan & Other Stories, Marlborough Fine Art, London, (1993).[4]

- Peter Pan - A Suite of 15 etchings and aquatints, Marlborough Graphics London (1993)[4]

- Collins, Judith and Linder, Elspeth (ed.). Writing on the Wall - Women Writers on Women Artists, Tate Gallery, published by Weidenfeld & Nicholson, London (1993)[4]

- Searle, Adrian. Unbound - Possibilities in Painting, Hayward Gallery, London, (1994).[4]

- Paula Rego: Dog Women, Marlborough Fine Art, London, (1994).[4]

- Saligmen, Patricia (ed.). An American Passion - The Susan Kasen Summer and Robert D. Summer Collection of Contemporary British Paintings, (1995).[4]

- Spellbound - Art and Film, Hayward Gallery, London, text by Marcia Pointon (1994)[4]

- Paula Rego: The Dancing Ostriches from Disney's Fantasia, Marlborough Fine Art, London and Saatchi Collection, London. Introduction by Sarah Kent, essay by John McEwen (1996)[4]

- Desmond Shawe-Taylor, Desmond. Paula Rego, Dulwich Picture Gallery, (1998).[4]

- Hyman, Timothy and Malbert, Roger. Carnivalesque, Hayward Gallery, (2000).[4]

- Coles,Pippa; Higgs, Matthew and Poncelet, Jacqui. British Art Show 5, Hayward Gallery, (2001).[4]

- McCaughey, Patrick; Cork, Richard and Weeks, Emily M. The School of London and their Friends – The Collection of Elaine and Melvin Merians, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, Neuberger Museum of Art, Purchase, USA. (2001).[4]

- Warner, Marina. Metamorphing, The Science Museum, London, (2002).[4]

- Paula Rego- Jane Eyre, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, (2002).[4]

- Paula Rego, Serralves Museum, Oporto, (2004).[4]

Books

- José Augusto França: Pintura portuguesa no século XX, Livraria Bertrand, Lisbon, (1974)[4]

- Rui Mário Gonçalves: Pintura e escultura em Portugal, 1940–1980, Lisbon, Instituto de Cultura, Lisbon (1984)[4]

- Alexandre Melo e Joao Pinharanda: Arte Contemporânea Portuguesa, Lisbon (1986)[4]

- Bernardo Pinto de Almeida: Breve introdução à pintura portuguesa no século XX, Edição do Author, Oportof (1986)[4]

- Nursery Rhymes, Thames and Hudson (1989)[4]

- Hector Obalk: Paula Rego, Art Random, Kyoto Shoin International Co. Ltd., Kyoto, Japan (1991)[4]

- John McEwen: Paula Rego, Phaidon Press Ltd., London (1992)[4]

- The Art Book, Phaidon Press Ltd, London (1993)[4]

- Peter Pan, Folio Society (1993)[4]

- Marina Warner, Wonder Tales, Chatto & Windus, London (1994)[4]

- "A Portfolio - Nine London Birds, Byam Shaw School of Art, London, introduction by John McEwen (1994)[4]

- Diana Eccles and Barbara Putt (ed.), British Council Collection Catalogue Volume II (1995)[4]

- John McEwen, Paula Rego, Phaidon Press, London (1996)[4]

- Blake Morrison, Pendle Witches, Enitharmon Press, London (1996)[4]

- John McEwen, Dancing Ostriches, Saatchi Publications (1996)[4]

- Paula Rego, Tate Gallery Publications (1997)[4]

- Colin Wiggins, Paula Rego, Dictionary of Women Artists, Volume I, pp 1155–1159, edited by Delia Gaze, Fitzroy Dearborn Publishers, London

- Frances Borzello, Seeing Ourselves - Women's self-portraits, Thames & Hudson, London, pp 26, 177, 214, (1998).[4]

- Alexandre Melo, Artes Plàsticas em Portugal, Dos Anos 70 aos nossos Dias, Difel, Portugal, pp 28–31 & pp 104 – 107, (1998).[4]

- Elizabeth Cayzer, Changing Perceptions - Milestones in Twentieth-Century British Portraiture, The Alpha Press, Brighton, pg.87 – 91, (1998).[4]

- Marco Livingstone, Paula Rego - Grooming, in Art: The Critics' Choice, Aurum Press, London (1998).[4]

- Elizabeth Drury, Self Portraits of the World’s Greatest Painters, Parkgate Books, 1999, pg. 306 (1998)[4]

- Ruth Rosengarten, Getting Away with Murder – Paula Rego and the crime of Father Amaro, Delos Press, Birmingham (1999)

- Ruth Rosengarten, Paula Rego e O Crime do Padre Amaro, Quetzal Editores, Lisbon (1999)[4]

- Andrew Graham-Dixon, The Art of Success, Portraits by Snowdon, Vogue, May (2000)[4]

- Chris Dunn, People Looking at Art, Hodder & Stoughton, London (2000)[4]

- Fiona Bradley (ed.), Victor Willing, August Publishers (2000)[4]

- Fiona Bradley, Paula Rego, Tate Publishing (2002)[4]

- Neil MacGregor, The Daily Telegraph Britain’s Paintings, Cassell Illustrated, pg. 57 (2002)[4]

- Maria Manuel Lisboa, Paula Rego’s Map of Memory: National and Sexual Politics, Ashgate Publishing Ltd., Hampshire (2003)[4]

- Stephen Stuart-Smith with introduction by Marina Warner, Paula Rego – Jane Eyre, Enitharmon Editions, London (2003)[4]

- T.G. Rosenthal, Paula Rego: The Complete Graphic Work I, Thames & Hudson, London (2003)[4]

- Ruth Rosengarten, Compreender Paula Rego – 25 Perspectivas, Publico Serralves (2004)[4]

- T. G. Rosenthal, Paula Rego: The Complete Graphic Work II, Thames & Hudson, London, (2003).[4]

- Ruth Rosengarten, "Narrating the Family Romance: Love and Authority in the Work of Paula Rego", Manchester University Press, (2011).

- T. G. Rosenthal, Paula Rego: The Complete Graphic Work, Thames & Hudson, London (2012)

Public collections

Rego's works can be found in a number of public institutions, including:

- Abbot Hall Art Gallery, Kendal[33]

- Arts Council England[33]

- Berardo Collection Museum, Sintra Museum of Modern Art, Portugal[33]

- British Council, London[33]

- British Museum, London[33]

- Bristol City Museum and Art Gallery[33]

- Chapel of the Palacio de Belém, Lisbon

- Frissiras Museum, Athens

- Leeds Art Gallery[33]

- Gulbenkian Foundation, Lisbon

- Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

- National Gallery, London[33]

- National Portrait Gallery, London[33]

- New Hall, Cambridge

- Rugby Museum and Art Gallery[33]

- Tate Gallery, London

- Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester[33]

- Yale Center for British Art[33]

Recognition

Rego has received honorary doctorates from the Winchester School of Art, the University of East Anglia, the Rhode Island School of Design and the University of Oxford.[5] In 2004 she was awarded the Grã Cruz da Ordem de Sant'Iago da Espada by the President of Portugal.[5]

In 2009 a museum dedicated to Rego's work and designed by the architect Eduardo Souto de Moura, the Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, was opened in Cascais, Portugal and several key exhibitions of her work have since been staged here.[34]

In 2010, Rego was made a Dame of the British Empire in the Queen's Birthday Honours.[35] In 2010 Rego also won the MAPFRE Foundation Drawing Prize in Madrid.[36]

Personal life

Rego is a supporter of S.L. Benfica, just like her grandfather who was a founding member of the club.[37]

See also

References

- ↑ "Biography: Paula Rego", Marlborough Fine Art, Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ Kellaway, Kate. "Artists: Paula Rego", The London Group, Retrieve 23 May 2014.

- 1 2 Patterson, Christina. "Paula Rego's private world", The Independent, Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 61 62 63 64 65 66 67 68 69 70 71 "Paula Rego", Saatchi Gallery, Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Paula Rego Biography", Casa da Historias, Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 Brown, Mick. "Paula Rego interview", The Telegraph, Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ↑ John McEwen, Paula Rego (Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1992) p.25f

- ↑ "Victor Willing: Biography", Casa das Historias Paula Rego, Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ↑ Fiona Bradley (ed.), Victor Willing (London: August Media, 2000) p.10f

- ↑ "ICA Exhibitions", Institute of Contemporary Art, Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ↑ "Group Exhibitions", Casa das Historias Paula Rego, Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ Tate Gallery Archives, London, ref. TGA978

- ↑ "Biography", Marlborough Gallery, Retrieved 23 May 2014.

- ↑ Ian Chilvers (2004). The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0 19 860476 9.

- ↑ "Paula Rego", Marlborough Fine Art, Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ Sue Hubbard, "Paula Rego", Print Quarterly, March 2013, pp. 112-15.

- ↑ Victor Willing, 'The Imagiconography of Paula Rego', in Tate Gallery, Paula Rego (London: Tate Publishing, 1997) p.37

- ↑ Fiona Bradley, 'Introduction: Automatic Narratives', in Tate Gallery, Paula Rego (London: Tate Publishing, 1997) p.9f

- ↑ Ruth Rosengarten, 'Home Truths: The Work of Paula Rego', in Tate Gallery, Paula Rego (London: Tate Publishing, 1997) p.44

- ↑ Judith Collins, 'Paula Rego's Drawings', in Tate Gallery, Paula Rego (London: Tate Publishing, 1997) p.121f

- ↑ John McEwen, Paula Rego (Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1992) p.52-6

- ↑ "About the Associate Artist Scheme | Learning | National Gallery, London". www.nationalgallery.org.uk. Retrieved 2016-03-08.

- ↑ Ruth Rosengarten, 'Home Truths: The Work of Paula Rego', in Tate Gallery, Paula Rego (London: Tate Publishing, 1997) p.75

- 1 2 Secher, Benjamin. "In the studio: Paula Rego", The Daily Telegraph, Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ John McEwen, Paula Rego (Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1992) p.47

- ↑ Fiona Bradley, 'Introduction: Automatic Narratives', in Tate Gallery, Paula Rego (London: Tate Publishing, 1997) p.13-19

- ↑ Fiona Bradley, 'Introduction: Automatic Narratives', in Tate Gallery, Paula Rego (London: Tate Publishing, 1997) p.19

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 "Solo Exhibitions", Casa das Historias, Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ "Paula Rego Tate", Tate Liverpool, Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ "Paula Rego Solo Exhibitions", Marlborough Fine Art, Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ "Paula Rego", Tate Britain, Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ "Paula Rego", Museo Reina Sofia, Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Public Collections", Casa das Historias Paula Rego, Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ "Building", Casa das Historias Paula Rego, Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ Melkle, James. "Queen's birthday honours list: the arts", The Guardian, Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ "Penagos Drawing Award 2008-2012", Fundacion Mapfre, Retrieved 22 May 2014.

- ↑ "Paula Rego: "O meu clube é o Benfica"" [Paula Rego: "My club is Benfica"]. Record (in Portuguese). Lusa. 22 May 2014. Retrieved 26 December 2014.

Further reading

- Paula Rego (London: Tate Publishing, 1997)

- John McEwen, Paula Rego (Oxford: Phaidon Press, 1992)

- Maria Manuel Lisboa, "Paula Rego's Map of Memory: National and Sexual Politics" (London: Ashgate, 2003)

- Fiona Bradley, Paula Rego (London: Tate Publishing, 2002)

External links

- Paintings by Paula Rego at the Art UK site

- Casa das Histórias Paula Rego, Museum Page

- Marlborough Art Gallery, artists' page

- Tate: In the Studio: Paula Rego Printmaking with the artist at The Curwen Studio. 31 July 2008

- Art HERStory: Paula Rego